This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Journeys Through Bookland, Vol. 10

The Guide

Author: Charles Herbert Sylvester

Release Date: March 16, 2008 [eBook #24857]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK JOURNEYS THROUGH BOOKLAND, VOL. 10***

Transcriber’s Note

Obvious typographical errors have been corrected. A list of these changes is found at the end of the text. Inconsistencies in spelling and hyphenation have been maintained. A list of inconsistently spelled and hyphenated words is found at the end of the text.

A NEW AND ORIGINAL

PLAN FOR READING APPLIED TO THE

WORLD’S BEST LITERATURE

FOR CHILDREN

BY

CHARLES H. SYLVESTER

Author of English and American Literature

VOLUME TEN—THE GUIDE

New Edition

For parents, teachers, and all who have

children under their charge; for adult

who wish to renew their acquaintance

with the friends of their youth, or to

open for the first time the world’s great

treasure house of literature; for youthful

readers who must study the classics

Chicago

BELLOWS-REEVE COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1922

BELLOWS-REEVE COMPANY

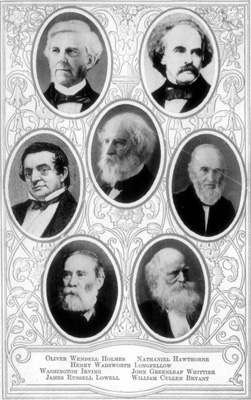

Halftone Portraits of Authors

| PAGE | ||

| Group One | Frontispiece | |

| Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Oliver Wendell Holmes Nathaniel Hawthorne Washington Irving John Greenleaf Whittier James Russell Lowell William Cullen Bryant |

||

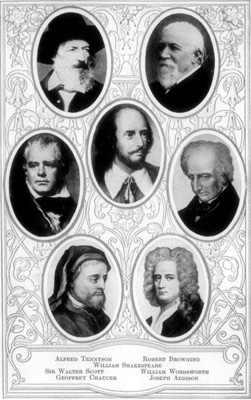

| Group Two | 52 | |

| William Shakespeare Alfred, Lord Tennyson Robert Browning Sir Walter Scott William Wordsworth Geoffrey Chaucer Joseph Addison |

||

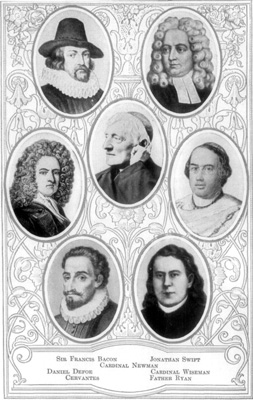

| Group Three | 100 | |

| Cardinal Newman Sir Francis Bacon Jonathan Swift Daniel Defoe Cardinal Wiseman Cervantes Father Ryan |

||

| Group Four | 148 | |

| Julia Ward Howe Benjamin Franklin Henry David Thoreau Patrick Henry William H. Prescott Francis Parkman James Fenimore Cooper |

||

| Group Five | 198 | |

| Edgar Allan Poe Donald G. Mitchell James Whitcomb Riley Thomas Buchanan Read Eugene Field [xiv]John Howard Payne John G. Saxe |

||

| Group Six | 246 | |

| Elizabeth Barrett Browning Phoebe Cary Alice Cary Lucy Larcom Felicia Hemans George Eliot Jean Ingelow |

||

| Group Seven | 294 | |

| Robert Burns Robert Southey William Cowper Lord Byron John Keats Percy Bysshe Shelley Samuel Taylor Coleridge |

||

| Group Eight | 342 | |

| Rudyard Kipling Robert Louis Stevenson Paul Du Chaillu Thomas Hughes Hans Christian Andersen Jakob Grimm Wilhelm Grimm |

||

| Group Nine | 400 | |

| John Ruskin Oliver Goldsmith Matthew Arnold Thomas Babington Macaulay John Bunyan Thomas De Quincey Charles Lamb |

||

| Group Ten | 454 | |

| John Tyndall Charles Kingsley Thomas Moore Alexander Pope Thomas Campbell David Livingstone George MacDonald |

Everyone who associates with children becomes deeply interested in them. Their helplessness during their early years appeals warmly to sympathy; their acute desire to learn and their responsiveness to suggestion make teaching a delight; their loyalty and devotion warm the heart and inspire the wish to do the things that count for most. Everything combines to increase a sense of responsibility and to make the elders active in bringing to bear those influences that make for character, power and success.

Every worthy teacher in every school gives more than her salary commands and puts heart power into every act. By example and precept the lessons are taught and growth follows in response to cultivation. But the schools are handicapped by lack of time for much personal care, by lack of facilities for the best of instruction and by the multiplicity of things that must be done. Under the best conditions a teacher has but a small part of a child’s time and then instruction must be given usually to classes and not to individuals. Outside of school for a considerable time each day the child falls under the influence of playmates who may or may not be helpful, but the greater part of every twenty-four hours belongs to the home.

[2]Parents, guardians, brothers and sisters, servants, consciously or unconsciously, wisely or unwisely, are teaching all the time. It is from this great complex of influences that every child builds his character and lays the foundation of whatever success he afterwards achieves.

Undoubtedly the home is the greatest single influence and that is strongest during the early years. Before a boy is seven the elements of his character begin to form; by the time he is fourteen his future usually can be predicted, and after he is twenty, few real changes are brought about in the character of the man. The schools can do little more than plant the seeds of culture; in the family must the young plants be watered, nourished and trained. Then will the growth be symmetrical and beautiful.

When the school and the home work together, when parents and teacher are in hearty sympathy, the great work is easily accomplished. But this harmony in interest is difficult to secure. In the first place it is not possible frequently for parents and teachers to become acquainted; usually is it impossible for them to know one another intimately. Here there are two forces, each ignorant of the other, but both trying for a common end. Again, parents in many, many instances are not acquainted with the schools nor with the methods of instruction which are followed therein. What is done by one may be undone by the other. If there could be a common ground of meeting, much labor would be saved and greater harmony of effort established.

When fathers and mothers are willing to take time enough from their other duties to show that [3]sympathetic interest in juvenile tasks which is the greatest stimulus to intelligent effort, when they wish to know what work each child is doing and where in each text book his lessons are, when the multiplication table and the story of Cinderella are of as much importance as the price of meat or the profit on a yard of silk, then will the parents and the teachers come together in whatever field appears mutually acceptable.

Everybody reads, and reading is now the greatest single influence upon humanity. The day of the orator has passed, the day of print has long been upon us. No adult remains long uninfluenced by what he reads persistently, and every child receives more impressions from his reading than from all other sources put together.

Someone has shown forcibly by a graphic diagram the ideas we are most anxious to establish. In this diagram of Forces in Education, the circle represents the sum total of all those influences which tend to make the mind and character of the growing child. That half of the circle to the right of the heavy line represents the forces of the school; the half to the left, the forces that come into play outside the teacher’s domain. In school are the various studies taught; reading, writing, language, nature, geography, history, arithmetic. Other things such as morals, manners, hygiene, etc., come in for their share of force in the division “Miscellaneous.” Out of school the child’s work influences him; his playmates affect him more; the example and instruction of his parents form his habits, thought and character to a still greater extent; but more than any one, as much as the three [4]combined, does his home reading shape his destiny.

That this last statement is no exaggeration is proved by the testimony of many a wise and thoughtful man, by the observation of teachers everywhere. When a child has learned to read, he possesses the instrument of highest culture, but at the same time the instrument of greater danger. Bad books or bad methods of reading good books lead the reader’s mind astray or stimulate a destructive imagination that affects character forever; but good books and right methods of reading make the soul sensitive to right and wrong, improve the mind, inspire to higher ideals and lead to loftier effort.

[5]Here is the one fertile field wherein teacher, parent and every other person interested in the welfare of children and youth may meet and work together in the noblest cause God ever gave us the grace to see.

“I have a notion,” said Benjamin Harrison, “that children are about the only people we can do anything for. When we get to be men and women we are either spoiled or improved. The work is done.” One of the best things we can do is to create a taste for good reading and cultivate a habit of reading in the right manner. It is an easy and a delightful task.

How many parents do it? Let them live with their children in the realm the little ones love. Let them read the fairy tales, the myths, the stories, the history that childhood appreciates, not in a spirit of criticism or in the role of a dictator but as a child of a little larger growth, a man or woman with a youthful mind.

How many teachers assist? By so teaching that reading becomes an inspiration in itself; that only mastery contents; that beauty, high sentiment, lofty ideals may be found and followed; by making the reading recitation the one delightful hour of the day.

If any mature person at home can spend each week a few hours in reading and talking with the children about what has been read he will be surprised to find how lightly the time passes and how quickly his own cares and anxieties are dissipated. He will find greater delight than he has ever known in the society of his equals; and the younger ones, whose minds glow with helpful curiosity and [6]absorbing interest will be kept to that extent from the street and its attractions, while at the same time they are learning those things that count for most in life’s great battle.

Let no one feel in the least uncertain of his power to interest and delight. Let him have no hesitation in joining in with the children, in meeting them on their level and in sharing thought and feeling with them. By being a child himself he most easily makes of himself a wise and inspiring leader.

Journeys Through Bookland is what the title signifies, a series of excursions into the field of the world’s greatest literature. Accordingly, the base of the work is laid in those great classics that, since first they found expression in words, have been the education and inspiration of man. But these excursions are taken hand-in-hand with a leader, whose province it is to explain, to interpret, to guide and to direct. Suiting his labors to the age and acquirement of the readers he helps them all, from the child halting in his early attempts to interpret the printed page to the high school or college student who wishes to master the innermost secrets of literature. In no small sense is this leadership a labor of love, for it follows an experience of twenty years of personal instruction in the public schools and among the teachers of the country.

Journeys Through Bookland must be considered as a unit; for one plan, one purpose, controls from the first page of the first volume to the last page of the tenth. The literary selections were not chosen haphazard nor were they graded and arranged after any ordinary plan. In this respect they differ in character and arrangement from the selections in any other work now upon the market.

[8]Moreover, the notes, interpretations, original articles and multifarious helps are an integral part and are inseparable. In this respect, again, is the work original and unique.

Further, the pictures, of which there are many hundreds, were drawn or painted expressly for Journeys Through Bookland and are as much a part of the general scheme as any other help to appreciation. Again, the type page, the decorations, the paper, binding and endsheets, all combine to give an artistic setting to literary masterpieces and a stimulating atmosphere for literary study.

The masterpieces which make the field of the Journeys naturally fall into three classes. First, there is the literature of culture, those things which you and I and everybody must know if we expect to be considered educated or to be able to read with intelligence and appreciation the current writings of the day. To this class belong all those nursery rhymes, lyrics, classic myths, legends and so on to which allusion is constantly made and which are themselves the legal tender of polite and cultured conversation. Next, there are those selections whose power lies in the profound influence they exert upon the unfolding character of boy or girl. As a child readeth so is he. Masterpieces of this type abound in the books and it is by means of them that the author hopes and expects to exert his greatest influence upon his unknown friends among the children. The third group consists of the masterpieces which lend interest to school work and make it pleasanter, easier and more profitable. It is what some may call the practical side of litera[9]ture. It is what, at first, appeals most strongly to those who have read little, but which ultimately appears of less value than the influence of cultural and character-building literature.

Any treatment of Journeys that is worthy of the name must consider the masterpieces themselves in their three great functions, as well as the devices by which the selections are made effective.

The table of contents at the beginning of each volume shows a wide selection of the best things that have ever been written for children—not always the new things, but always the best things for the purpose. The masterpieces are the tried and true ones that have long been popular with children and have formed a large part of the literary education of the race.

There are a host of complete masterpieces and many selections from other works which are too long to print here or which are otherwise unavailable. It has often happened that something written for older heads and for serious purposes has in it some of the most charming and helpful things for the young. For instance, Gulliver’s Travels is a political satire, and as such it is long since dead. Yet parts of it make the most fascinating reading for children. Moreover, Swift and many other great writers defiled their pages with matter which ought to be unprintable. To bring together the good things from such writers, to reprint them with all the graces of style they originally possessed, and yet so carefully to edit them that there [10]can be no suggestion of offense, has been the constant aim of the writer.

The books contain, too, many beautiful selections translated from foreign languages and made fresh, attractive and inspiring. Many of the old fables and folk stories have been rewritten, but others which have existed long in good form have been left untouched. In the great masterpieces no liberties have been taken with the text without making known the fact, and in every case the most reliable edition has been followed. It is hoped that children will have nothing to “unlearn” from the reading of these books.

There are not a few old things in the set that are really new, because they have heretofore been inaccessible to children except in musty books not likely to be met.

This is no haphazard collection made hastily, and largely at the suggestion of others. Everything in the books has been read and reread by the writer. True, he has availed himself of the help of others, and to many his obligations are deep and lasting; but in the end the responsibility for selection and for the quantity and quality of the helps is wholly his.

The contents of the books have been graded from the nursery rhymes in the first volume to the rather difficult selections in the ninth volume. In the arrangement, however, not all the simplest reading is in the first volume. It might be better understood if we [11]say that one volume overlaps another, so that, for instance, the latter part of the first volume is more difficult than the first part of the second volume. When a child is able to read in the third volume he will find something to interest him in all the volumes.

What has been said, however, does not wholly explain the system of arrangement. Fiction, poetry, essays, biography, nature-study, science and history are all fairly represented in the selections, but no book is given over exclusively to any subject. Rather is it so arranged that the child who reads by course will traverse nearly every subject in every volume, and to him the different subjects will be presented logically in the order in which his growing mind demands them. We might say that as he reads from volume to volume, he travels in an ever widening and rising spiral. The fiction of the first volume consists of fables, fairy tales and folk stories; the poetry of nursery rhymes and children’s verses; the biography of anecdotal sketches of Field and Stevenson; and history is suggested in the quaintly written Story of Joseph. On a subsequent turn of the spiral are found fiction from Scott and Swift; poetry from Homer, Vergil, Hay, Gilbert and Tennyson; hero stories from Malory; history from Washington Irving.

If, however, some inquiring young person should wish to read all there is on history, biography or any other subject, the full index in the tenth volume will show him where everything of the nature he wishes is to be found.

Another valuable feature of arrangement is the frequent bringing together of selections that bear [12]some relation to one another. A simple cycle of this sort may be seen where in the eighth volume the account of Lord Nelson’s great naval victory is followed by Casabianca; a better one where in the fifth volume there is an account of King Arthur, followed by tales of the Round Table Knights from Malory, and Geraint and Enid and The Passing of Arthur from Tennyson. By this plan one selection serves as the setting for another, and a child often can see how the real things of life prove the inspiration for great writers. Again, in the fourth volume is The Pine Tree Shillings, a New England story or tradition for girls; this is followed immediately by The Sunken Treasure, a vivid story for boys; next comes The Hutchinson Mob, a semi-historical sketch, followed in turn by The Boston Massacre, which is pure history. The cycle is completed by The Landing of the Pilgrims and Sheridan’s Ride, two historical poems.

Graphic Classification of Masterpieces on page 14 will show more clearly what is meant by the overlapping of subjects. In the column at the left are given the names of the subjects under which the selections have been classified, running from Fables to Drama, and Studies, the last name including all the varied helps given by the author. Across the top of the table the Roman numerals, I to X, indicate the numbers of the ten volumes. The shading in the squares shows the relative quantity of material. In using the Classification, “read across to learn in which volume the subjects are treated; read down to find what each volume contains.” Thus: The first volume contains (reading down), a great many fables, many fairy stories and [13]much folk lore, a few myths and old stories, a little biography, some biblical or religious material, selections that may be classified under the heads of nature, humor and poetry; but there is no account of legendary heroes, no travel and adventure, no history, nothing of a patriotic nature and no drama. On the other hand (reading across), there are many fables in the first volume, a few in the second but none thereafter; a few myths and some classic literature are found in the first three volumes, more in the fourth and fifth, but the number and quantity decrease in the sixth and do not appear thereafter; nature work is to be found in all the volumes but is strongest in the seventh; drama appears in the eighth and the ninth. Biography has a place in all volumes, but is strongest in the seventh; while the Studies, appearing in all volumes, reach their highest point in the tenth.

As has been said, the chief factors in making Journeys Through Bookland unique and of greatest value are the many helps that are given the readers, young and old. These helps are varied in character and are widely distributed through the volumes. They must be considered one at a time by the person who would assist others to use them to the best purpose. These helps consist of what are technically known as studies, notes, introductory notes, biographies, pronouncing vocabularies, pictures, tables of contents and index. The following comments will make clear the purpose of each.

Graphic Classification of Masterpieces

| Analysis | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX | X |

| Fables | Volume X is a Guide for Parents, Teachers and Students |

|||||||||

| Fairy Stories Folk Lore |

||||||||||

| Stories Old and New |

||||||||||

| Myths and Classic Literature |

||||||||||

| Legendary Heroes | ||||||||||

| Biography | ||||||||||

| Travel and Adventure | ||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||

| Biblical, Moral, Religious | ||||||||||

| Patriotism | ||||||||||

| Nature | ||||||||||

| Humor | ||||||||||

| Poetry | ||||||||||

| Drama | ||||||||||

| Studies |

Read across to learn in which volumes the subjects are treated; read down to find what each volume contains.

[15]a. Studies. Every volume contains a large number of helps of different kinds for young people. Usually these are in connection with some selection and are adapted to the age of the boy or girl most likely to read the piece. As each study is presented in an interesting and informal manner and does not cover many points, it is felt that young people will enjoy them only less than the masterpieces themselves.

The studies are arranged as systematically as the selections, and are graded even more carefully. Their scope and method will be more fully explained in subsequent sections of this volume.

b. Notes. These consist of explanatory notes, that are placed wherever they seem to be needed. They explain words not usually found readily in the dictionaries, foreign phrases, and such historical or other allusions as are necessary to an understanding of the text by youthful readers. These notes are placed at the bottom of the page that needs explanation, and so are immediately available. In such a position they are more liable to be read than if gathered together at the end of the volume. They are neither formal nor pedantic, and are as brief as is consistent with clearness. Their purpose is to help the reader, not to show the writer’s knowledge.

c. Introductory Notes. At the heads of selections from longer masterpieces are introductory notes which give some little account of the larger work and enough of the context so that the selection may not seem a fragment. In some instances this note gives the historical setting of a masterpiece or tells something of the circumstances under [16]which it was written, when those facts help to an appreciation of the selection. Sometimes an acquaintance with the personality of an author is so necessary to a clear understanding of what he writes that a brief sketch of his life or a few anecdotes that show his character are given in the note preceding what he has written. These notes are printed in the same type as the text, especially in the first four volumes, for they are felt to be worthy of equal consideration.

d. Biographies. Besides the biographical notes appended to selections, there are not a few more pretentious sketches that have been given prominent titles in the body of the books. These have been prepared expressly for this work, either by the editor or by some one fully acquainted with the subject and accustomed to writing for young people. These biographies are written from the point of view of young people, and contain the things that boys and girls like to know about their favorite authors or some of the noble men and women whose lives have made this world a better and a happier place in which to live. In the earlier volumes they are brief, simple, and largely made up of anecdotes; later they are more mature, and show something of the reasons that make the lives interesting and valuable material for studies. There are, also, in the books a few lengthy extracts from some of the world’s great biographies. Care has been exercised in the selection of these, so that in each case, while the extract is of interest to young people, it is also fairly representative of the larger work from which it has been taken.

e. Pronouncing Vocabularies. Children often [17]find difficulty in pronouncing proper names, and not many have at hand any books from which they can obtain the information. At the end of every volume is a list of the important proper names in that book, and after each name the pronunciation is given phonetically, so that no dictionary or other reference work is necessary. Since each volume has its own list, it is not necessary even to lay down the book in hand and take up the last volume.

f. Pictures. The illustrations in the several volumes form one great feature in the general plan. They alone will do much to interest children in the reading, and if attention is called to them they will be found to increase in value. The color plates in each volume, the numerous fine halftones of special design, and the hundreds of pen and ink drawings that illuminate the text have been painted and drawn for these books, and will be found nowhere else. More than twenty artists have given their skill and enthusiasm to make the books brighter, clearer, and more inspiring. The initial letters and the many fine decorations also belong exclusively to the set, and combine to give it esthetic value. Everything of this nature will command attention and hold interest.

g. Tables of Contents. Beginning each volume is a table showing the contents of the volume and the names of authors. It forms a means of ready reference to the larger divisions of the work and is a handy supplement to the index.

h. Index. At the end of the tenth volume is an index to the whole ten volumes. There may be found not only each author and title in alphabetical order, but also a complete classification of the selec[18]tions in the set. To find the history in this series, look in the index under the title “History.” When a topic has as many sub-divisions as has “Fiction,” for instance, or “Poetry,” cross references are given.

When a child is taught the little nursery rhymes which to us may seem to be meaningless jingles, he is really peeping into the fields of literature, taking the first steps in those journeys that will end in Shakespeare, Browning and Goethe. When his infantile ear is caught by the lively rhythm and the catchy rhymes, he is receiving his first lessons in poetry. That the lessons are delightful now he shows by his smiles, and in middle life he will appreciate the joy more keenly as he teaches the same little rhymes to his own children.

Most children know the rhymes when they come to school and they will like to read them there. A child’s keenest interest is in the things he knows. Later, perhaps in the high school or the grammar grades, he will be interested again in learning that the rhymes are not wholly frivolous and that there may be reasons why these rhymes should have survived for centuries in practically unchanged forms. Some of the facts that may be brought out at various times are the following:

I. There is a hidden significance in some of the nursery rhymes. For instance:

a. Daffy-Down-Dilly (page 47). In England one of the earliest and most common of spring [19]flowers is the daffodil, a bright yellow, lily-like blossom, with long, narrow green leaves all growing from the bulb. The American child may know them as the big double monstrosities the florist sells in the spring, or he may have some single and prettier ones growing in his garden. The jonquil and the various kinds of narcissus are nearly related white or white and pink flowers. This picture on page 47 of Journeys Through Bookland shows a few daffodils growing. Miss Daffy-Down-Dilly, then, in her yellow petticoat and her green gown, is the pretty flower; and the rhyme so understood brings a breath of spring with it.

b. Humpty Dumpty (page 55). This is really a riddle of the old-fashioned kind. There are many of them in English folk lore. Usually a verse was repeated and then a question asked; as, “Who was Humpty Dumpty?” The artist has answered the question for us in the picture. Possibly many people who learned the rhyme in childhood never thought of Humpty as an egg.

What answer would you give to the question, Who was Taffy (page 54)? For similar riddles, see Nancy Netticoat (Vol. I, p. 72), The Andiron (page 245) and St. Ives (page 202).

II. Some were intended to teach certain facts. For instance:

a. When children were taught the alphabet as the first step to reading, The Apple Pie (page 43) gave the letters in their order, including the obsolete “Ampersand.”

b. As children grew a little older and could begin to read what they already knew, things in which the same words were many times repeated were [20]helpful. Two examples are The House that Jack Built (page 56) and There Is the Key of the Kingdom (page 45).

c. The numbers from one to twenty were taught by One, Two (page 41).

d. The days of the week were taught by Solomon Grundy (page 42), which with its amusing provision for repetition is sure to catch the fancy of a child and keep his thoughts on the words.

III. Some of them teach kindness to animals:

a. Dapple Gray (page 22).

b. Ladybird (page 12). This is sometimes known as ladybug, and the bug is the little, round, reddish beetle whose wings are black dotted. It is a pretty, harmless beetle that gardeners like to see around their plants. Children repeat the rhyme when they find the beetle in the house and always release it to “fly away and save its children.”

c. Poor Robin (page 16).

d. Old Mother Hubbard’s amusing adventures with her dog (page 24) leave a very kindly feeling toward both.

IV. Some are philosophical, or inculcate moral precepts or good habits, in a simple or amusing way.

a. Early to Bed (page 34).

b. Little Bo-Peep (page 9). Is it not better to let cares and worries alone? Why cry about things that are lost?

c. Three Little Kittens (page 13) suggests care for our possessions.

d. There Was a Man (page 60) has the same idea that we often hear expressed in the proverb “A hair from the same dog will cure the wound.[21]”

e. Rainbow in the Morning (page 48) has some real weather wisdom in it.

f. There Was a Jolly Miller (page 47), gives a good lesson in contentment.

g. A Diller, A Dollar (page 59).

h. See a Pin (page 59) suggests in its harmless superstition a good lesson in economy.

i. Little Boy Blue (page 33) makes the lazy boy and the sluggard unpopular.

j. Come, Let’s to Bed (page 34) ridicules sleepiness, slowness and greediness.

V. Mother’s loving care, at morning and evening, when dressing and undressing the baby or when putting the little folks to bed, has prompted several of the rhymes:

a. This Little Pig (page 5) the mother repeats to the baby as she counts his little toes.

b. Pat-a-Cake (page 4) is another night or morning rhyme; and here mother “marks it with” the initial of her baby’s name and puts it in the oven for her baby and herself. Another of similar import is: Up, Little Baby (page 7).

c. Diddle, Diddle, Dumpling (page 7) has kept many a little boy awake till he was safely undressed.

d. What an old rhyme must Bye, Baby Bunting be (page 6)! It goes back to the days when “father went a-hunting, to get a rabbit skin to wrap Baby Bunting in.” Some one, more recently, has added the idea of buying the rabbit skin.

e. The simple little lyric, Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star (page 44) has filled many a childish soul with gentle wonder, and many a night-robed lassie has wandered to the window and begged the [22]little stars to keep on lighting the weary traveler in the dark.

VI. Some of the rhymes are pure fun, and even as such are worthy of a place in any person’s memory:

a. There Was an Old Woman (page 36); Great A (page 14); Jack Be Nimble (page 28); To Market, to Market (page 6), and There Was a Monkey (page 14); Goosey-Goosey (page 21); Hey, Diddle, Diddle (page 23); There Was a Rat (page 14), and others, belong to this category.

b. Three Blind Mice (page 12) is an old-fashioned Round. Many a band of little folks has been divided into groups and has sung the nonsensical rhymes until every boy and girl broke down in laughter. Do you poor modern people know how it was done? The school was divided into a half-dozen sections. The first section began to sing and when its members reached the end of the first line, the second section began; the third section began when the second reached the end of the first line, and so on till all sections were singing. When any section reached the word “As—” they began again at the beginning. The first line was chanted in a low, slow monotone, the others were sung as rapidly as possible to a rattling little tune on a high pitch. Imagine the noise, confusion and laughter. Many a dull afternoon in school has been broken up by it, and countless children have returned to their little tasks with new enthusiasm. The old things are not always to be scorned.

c. Old King Cole (page 52) is a jolly rhyme, and the illustration is one of the finest in the books. Everybody should study it.

[23]VII. Two, at least, of the rhymes are of the “counting out” kind. Often children want to determine who is to be “It” in a game of tag, who is to be blinded in a game of hide-and-seek, or who takes the disagreeable part in some other play. They are lined up and one begins to “count out” by repeating a senseless jingle, touching a playmate at each word. The one on whom the last word falls is “out,” safe from the unpleasant task. One at a time they are counted out till only the “It” remains.

Wire, brier and One-ery, Two-ery (page 51) are examples. The artist has shown a group being counted out, in her very lifelike picture on pages 50 and 51.

VIII. There are some errors in grammar in the rhymes, many words you cannot find in a dictionary, and some of the rhymes may seem a little coarse and vulgar; but they have lived so long in their present form that it seems almost a pity to change them. Encourage the older children to find the errors and to criticise and correct as much as they wish. Probably they will not like the rhymes in their new form and correct dress any better than we would.

IX. There is really a practical value, too, in a knowledge of the nursery rhymes. Allusions to them are found in all literature and many a sentence is unintelligible to him who does not recognize the nursery rhyme alluded to. It would be safe, almost, to say that not a day passes in which the daily papers do not contain allusions to some simple little lines dear to our childhood. They are not to be sneered at; they are to be loved in babyhood [24]and childhood, understood in youth, and treasured in middle life and old age.

Our Journeys Through Bookland contains a wealth of material and a host of studies and helps. It is not an easy matter to get even the plan of it into one’s mind in a few minutes. The object of this volume is to guide the parent, teacher or student and to show as many of the important phases of Journeys as is possible. In other chapters we take up different methods of reading or show ways in which the books can be used to accomplish certain definite purposes, and how to select the material needed for any occasion. By means of cross references to the other books this volume serves as a key to them all.

Volume One. The first sixty pages of this volume are given over to the best known of the old nursery rhymes. That they are old is one of their great merits. That all cultured people know them is proof of their value and interest. The words are old words but the pictures are new. Every one was drawn expressly for Journeys and all show the conception of artists who have not lost the appreciation of childhood. Little children love the rhymes and will learn them and repeat them at sight of the pictures long before they can read. Elsewhere in this volume are suggestions which show how the rhymes may be used profitably.

Journeys does not pretend to teach reading in the sense in which it is understood in the kindergarten and the early primary grades. Rather it begins to [25]be of service as a reader only after the child has been taught how to read for himself. Children in the third grade will read many stories for themselves; from the fourth grade on they are nearly all independent readers. Every teacher knows, however, that children like to listen to stories which it would be utterly impossible for them to read, and that later they best love to read the things which they have heard from the lips of parent or teacher. Therefore, the literature of the first volume forms a treasure house from which the parent may draw many a good story to tell, and where he may find more that will be excellent for him to read aloud. The taste for the best literature is often formed in early childhood. So no child is too young for Journeys and no child is too old. The real things we read over and over with increasing interest as the years go on. Elsewhere in this volume are directions for story-telling, and many especially good selections are named. What the parent shall read aloud is best left to him to determine; at first he will do well not to read aloud any of the comments with which the books are fitted. If he finds that the interest warrants it he can use the comments for himself and ask questions that will lead to thoughtful consideration of what is being read, even by very young children. The only thing necessary is that the reading should be taken seriously and that the parent should be as much interested as the youthful listener.

There are stories and poems, fairy tales and folk lore, biography in simple anecdotes of the great favorites of children and toward the end of the volume a few rather difficult selections for older [26]children. In this volume as in all of them it is hoped that parents will look over the table of contents again and again, select the things that seem best and suit them to the occasion. How beautiful the lullabies are for the babies, and how much the older boys and girls will enjoy them when read at baby’s side! When the children are interested in the whimsical rhymes of Stevenson, his biography should be read; and Eugene Field’s life is interesting when his sweet poems are lending their charm to the evening by the fireside. Some of the fables contain deep lessons that may be absorbed by the older children while the younger ones are interested in the story only.

Volume Two. The selections in the first part of the second volume are intentionally simpler than the last ones in the first volume. It is a good thing for a child to handle books, to learn to find what he wants in a book the greater part of which is too difficult for him. Oliver Wendell Holmes thought it was an excellent thing for himself that he had had the opportunity to “tumble around in a library” when he was a youngster. Every student who has had the opportunity so to indulge himself has felt the same thing. There are so many books published every month and so much reading to be done that a discriminating sense must be cultivated. No one can read it all or even a small part of it. Older people will discriminate by reading what they like. Children must learn to handle books and to find out what they are able to read. To put into their hands all they can read of the simple things they like is not wise. Most children read too much. Fairy stories are all right in their way, but to give a child [27]all the fairy tales he can read is a serious mistake. Hundreds of pretty, inane, senseless stories in attractive bindings with pretty, characterless illustrations tempt the children to vitiate their taste in reading, long before they are able by themselves to read the best literature.

Because they are valuable, there are fairy stories in Journeys; because their use may be abused, there are few of them; because something else should be read with them, they are not all in one volume nor in one place in a volume. The same rule of classification applies to other selections than fairy tales.

This is the volume in which the myths appear in the form of simple tales: three from the northland, two from Greece. Each story is attractive in itself, has some of the interest that surrounds a fairy tale and serves as the fore-shadowing of history. That they are something more than fairy tales is shown in the comments and elementary explanations that accompany them.

Little poems, lullabies, pretty things that children love are dropped into the pages here and there. Children seem to fear poetry after they have been in school a little while, largely because they have so much trouble in reading it aloud under the criticisms of the teacher and because the form has made the meaning a little difficult. It is, however, a great misfortune if a person grows up without an appreciation of poetry when it is so simple a matter to give the young an abiding love for it. A little help now and then, a word of appreciation, a manifestation of pleasure when reading it and almost without effort the child begins to read and love poetry as he does good prose.

[28]The beginnings of nature study appear in the second volume in the form of beautiful selections that encourage a love for birds and other animals, and Tom, The Water Baby, is a delightful story, half fairy tale, half natural history romance.

In this volume also is found The King of the Golden River, perhaps the best fairy story ever written.

Volume Three. A glance at the table of contents in the third volume will show the general nature of the selections. Fairy stories or tales with a highly imaginative basis predominate. There are some that are humorous, as for instance the selections from the writings of Lewis Carroll, and one or two of the poems.

The long selection from The Swiss Family Robinson is a good introduction to nature literature and contains all of the book that is worth reading by anyone. The two tales from The Arabian Nights are among the best in that collection and are perhaps the ones most frequently referred to in general literature and in conversation. The story of Beowulf and Grendel is a prose rendering of the oldest poem in the English language, and valuable for that reason. While it is rather terrifying in some of its details its unreality saves it from harmful possibilities. Parents and teachers are inclined rather to overestimate the unpleasant consequences of reading terrifying things when they are of this character. Few, if any, children will read the story if it displeases them and those who do will not retain the disagreeable impression it makes for any great length of time.

In this volume we begin our acquaintance with [29]the legendary heroes of the great nations. Frithiof, Siegfried, Robin Hood and Roland are all in this book, to be followed by Cid Campeador in Volume IV.

Volume Four. In this volume, with many fine poems and tales interspersed, is found the continuation of the legendary hero stories begun in Volume III, also as a natural sequence, a cycle of history that begins with a story and ends in a narrative of an actual historical occurrence. These may be found in the six selections beginning with The Pine-Tree Shillings. The article on Joan of Arc, the story of Pancratius and the account of Alfred the Great, though not related in any way, yet still serve to carry out the idea that this volume is largely an introduction to readings in history.

The Attack on the Castle is a stirring account of a mediæval battle. It prepares the way to the mediæval spirit made more prominent in the next volume. In The Arickara Indians the boys will begin to find the interest that the aborigines always have for our youth.

Volume Five. The legendary great, the half-historical personages that have been for so many centuries the inspiration of youths of many lands are found again in this volume in the person of the Greek heroes and, at much greater length, in England’s famous King Arthur. The story of his Round Table and its knights is told in an extremely interesting way. The spirit of Sir Thomas Malory is retained in his quaint accounts and Tennyson’s noble poems show how great a factor the legends of Arthur have been in literature. Besides the articles that are instructive there are a [30]few that are highly entertaining or merely humorous, for every child has a right to read sometimes for amusement only. It will be seen that some classes of literature have ceased to appear and that others are coming into view. The “spiral arrangement” is nicely illustrated in the reappearance of history and the legendary heroes and in the disappearance of myths and fairy tales, for which there is, however, some compensation in the highly imaginative Gulliver’s Travels, an extract from Dean Swift.

In this volume are also included a little cycle on one of the great heroes of the Scotch, Robert Bruce. These carry on the series of selections on legendary heroes, begun in Volume Three. These are followed by stories of adventure, of frontier life in the Central West, tales from the early history of our country. Reminiscences of a Pioneer, The Buccaneers, Captain Morgan at Maracaibo, and Braddock’s Defeat are examples of this kind of literature. These selections are authentic accounts from original sources and are among those things which boys really like, but which have not heretofore been accessible to them. Patriotic Poems, somewhat in the same vein, are given where they will be noticed and read.

Volume Six. In this volume the series of legendary and semi-historical selections is completed. It includes the best of the legends concerning the national hero of Persia, also the story of The Tournament from Ivanhoe, inserted here as a fitting introduction to Scott’s novels. There are several examples of nature studies in literature and several fine stories that have their place in the education of [31]everyone. The best of these stories and one of the finest ever written is Rab and His Friend. A cycle of a religious nature is found in those selections which are named The Imitation of Christ, The Destruction of Sennacherib, Ruth, and The Vision of Belshazzar.

The longest and best story in this book is A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens. This is a model in construction and furnishes the basis for all the studies that would naturally accompany the most elaborate piece of fiction.

The sixth volume is one of interest and one that will give plenty of opportunity for study to those who have the inclination to follow out the suggestions that accompany the selections. Close study should be upon those things which are already somewhat familiar. The high school student will find his time more profitably spent in working on the things in this volume than in poring over the more difficult masterpieces that are sometimes prescribed in courses of study. What we desire is power to read, understand and appreciate, and that is obtained by study upon those things that interest us and about which we know enough to enable us to use our minds to best advantage.

Volume Seven. On the whole, this is a more mature volume than any that has preceded it and yet there are some selections of a simple character inserted for the purpose of interesting those who cannot yet read very heavy literature. From this point on, however, there is little difference in the grade of the volumes. The way in which the literature is studied marks the difference in rank. In fact, when a person can read intelligently and with [32]appreciation such selections as appear in this volume he can read anything that is set before him. There may be some things that will require effort and perhaps explanation, but it is merely a question of vocabulary and parallel information. Besides the stories, there are selections in every department of literature except those that have been passed in the progress of the plan of grading. The legendary heroes, the myths and the stories of classic literature are no longer to be found. In their place are more selections on nature, more of biography and history and the real literature of inspiration. Some of the last group appear in the form of fine lyrics which everyone loves but which are made more attractive and inspiring by proper setting and helpful interpretations.

In this volume biography, which has had its share of attention in every volume, becomes a strong feature, especially in the fine sketches that are given of famous writers. It is a fact that most writers have lived so quietly and in such comparative seclusion that their lives are devoid of the exciting events that make the liveliest appeal to young people, yet every one has done so much for the world and in such varied ways that there are things in their lives that interest and enthrall the mind if only they are properly presented. Our great American writers have been noble men and women and their lives are models worthy of imitation. That is the thing for us to glory in and for our young people to know, for it is not by any means a universal fact that people who wrote inspiring literature have lived inspiring lives. The literature of nature is probably stronger in this volume than in any other and the selections [33]are of the most absorbing kind. It is not expected to give a vast amount of information but to create a love for reading about the great facts in nature and an appreciation of the beauties in the writings of those who love it. This is the last volume in which there is much fiction and it marks the beginnings of the really fine essays which form a large part of the succeeding volume. The history is of a higher type and includes excerpts from the writings of some of our greatest historians.

Volume Eight. The notable feature of the eighth volume is the selection from the plays of Shakespeare. Nothing is more important in the literary education of a child than his proper introduction to the greatest of our great writers, and this has been accomplished in the following manner. The Tempest was selected as the play, because it is simple and lively in its style, appeals to young people and has in it just enough of the marvelous, the beautiful and the terrible to make a decided impression on one who reads it for the first time. There are other plays that are greater but none that may be taught so easily to juvenile readers. In this volume there is a brief article on the reading of Shakespeare; this is followed by the inimitable tale of The Tempest by Charles and Mary Lamb; this by the play, The Tempest, practically as it was written; and this, in turn, by a long series of interesting studies on the drama. The whole is attractive from start to finish and the studies are certain to lead the reader to think.

The drama, then, is the new feature of the ninth volume, but this is also the volume of fine essays, the highest type of prose. The essays are best rep[34]resented by the following titles, all of which may be found in the table of contents of the eighth volume: The Alhambra by Irving, A Bed of Nettles by Allen, Dream Children, by Charles Lamb. These titles, too, show how broad is the field covered by the essay and how delightful a variety there may be in the one style of composition. The departments of Travel and Adventure, Patriotism and History have not been neglected. On the whole it is a serious volume, one which will give the high school student and the older members of the family a plentiful supply of good reading material and a suggestion of study for the evenings of many a winter day.

Volume Nine. Most of the selections in this volume are rather difficult reading for young people but there are helps enough to make the task a pleasant one. The series of essays, begun in Volume Eight is here continued, with The Ascent of the Jungfrau by Tyndall, A Dissertation upon Roast Pig and The Praise of Chimney Sweepers by Charles Lamb, and two representative essays by Sir Francis Bacon. The studies are of an advanced nature and if carried out as intended will be of decided service to high school students. In a few cases the selections are simple, like Robert of Lincoln, for instance, but the studies that accompany it are the more complete. It is hoped by such an arrangement to show how inexhaustible a field for study literature offers and how many things there are to be known about the least of our fine lyrics. The Ode on a Grecian Urn is of a different type. This poem makes no direct appeal to sentiment or to the knowledge of the average young [35]person, yet by study it is seen to be a lyric of exquisite beauty. This volume introduces the writings of several authors who have not before appeared because of their slight appeal to young people. Among them may be mentioned particularly Addison, Boswell, and Bacon. The volume contains also orations that should be studied as models, viz: The Gettysburg Address, The Fate of the Indians and The Call to Arms. Each has a series of studies following it. As a relief from the serious work of the volume there are included an extract from Pickwick Papers; that fascinating story, The Gold-Bug; and the delightful essay, Modestine, an extract from Travels with a Donkey, by Stevenson.

Volume Ten. At the end of this volume are given two tables; the first arranges the leading English writers chronologically, and the second follows a similar plan with the American authors. The index with which the book closes is for the entire series and enables the reader to find the selections readily, if he knows either the title or the name of the author; to find all the selections on any given topic; and to find the studies quickly if they are wanted. The index should prove as useful as any of the devices with which the books are filled.

In his excellent little book, How to Judge of a Picture, Van Dyke speaks of the things that constitute a good painting as follows: “First, it is good in tone, or possess a uniformity of tone that is refreshing to the eye; second, it is good in atmosphere—something you doubtless never thought could be expressed with a paint-brush; third, it is well composed, and a landscape requires composition as well as a figure piece; fourth, ‘values’ are well maintained, its qualities good, its poetic feeling excellent.” A second writer has said that beauty is manifested in four ways: by line, by light and shade, by color and by composition. We will consider these characteristics in order.

a. Line. We define the boundaries of objects and limit space by means of lines, and the use of lines constitutes drawing in pictures. These lines so used may be narrow or broad, straight or curved, perfect or broken, and definite or vague and undetermined. Upon their proper use, however, depends the beauty of proportion, the strength of personality and the impressions of truthfulness and reality. There are few rigid lines in nature. What we see is an impression of line, not sharp lines. If you look at a book you may see the sharp lines that [37]bound its edges but if you move it away a little or put it in shadow its boundaries are a little hazy and gradually you lose the impression of the lines that bound it and see only a book. A tree has no sharp outline except when it stands on a horizon and looks like a silhouette against the light. Ordinarily it is a mass of moving light and shade, of color. The leaves are not separately limited by lines and yet we know that leaves are there. If the artist drew each leaf separately and accurately the general effect would be extremely unnatural and instead of a tree we should see only the minute carefulness of a painter who had failed. Perfect lines, then, are rare in good pictures. The artist does not intend to make exact representations of reality but to convey the appearance of reality, and just in so far as he succeeds in conveying that appearance of reality is he successful. This does not mean that good drawing is not necessary in a picture; it merely tells you what constitutes good drawing. If the lines of the human figure are perfect it is almost certain that the figure will be strained, unnatural and without the appearance of life or motion. In a good picture the lines of good drawing are present but they are broken, subdued and lead into one another as do the lines we see in nature.

b. Light and Shade. It is the distribution of light and shadows in a picture that gives it the appearance of reality. A mere outline drawing is flat and has no semblance of life. The paintings of the ancient Egyptians are good examples of pictures that have no light and shade, and we all know how flat, stiff and unreal they appear. In pen and ink, and charcoal drawings, light is in[38]dicated by white and shadow by black, but between the two extremes are introduced various shades and tints of gray that make the variety of tone in shadows. This varying of the strength of shadows is everywhere in nature, though most of us are blind to it. In looking at any object for the purpose of distinguishing the lights and shades upon it we should half close our eyes and look intently at all parts of it. Under an inspection of this sort the building which we thought to be all of even light is seen to be dotted with patches of shadow of different intensity, showing that there are projections where the light from the sun strikes clearly or depressions into which it cannot enter so freely. A picture should give the same effect, and it is this effect, which includes also the distance from the eye as well as the shades from the light source, that we call “values.” If we look at a tree in the way described we see that it is covered with patches of green in light or dark tints and that these color values are the lights and shades of which we are speaking. There will be one point of highest light and an opposing point of deepest shadow, and upon the proper arrangement of these as well as upon the patches of minor importance depends the lifelike appearance of the objects in the picture. Van Dyke says there are three things concerning light and shade that should be looked for in every picture, viz.: that everything, no matter how small it be, has its due proportion of light and shade; that there be one point of compass from which the light comes; that there be a center of light in the picture itself, from which all other lights radiate and decrease until they are lost in the color or shadow.

[39]c. Tone and Color. The first thing that seizes the eye in a painting is color, and the brightest, gayest colors are the ones that are most likely to attract. In fact they are the only colors that the inexperienced may see, for many a person is blind to the subdued tints and shades that are really the most attractive to the trained eye. Good coloring, then, does not mean brightness alone. It is the relationship, the qualities and the suitableness of colors one to another, whether they be in shadow, half-tint or light, that constitute good coloring. Brilliant dresses and inharmonious ornaments strike the refined eye with displeasure, the wearer is “loud” in her dress. Subdued colors relieved here and there with a harmonious dash of brightness show correct taste. So in pictures those that have the low or deep tones, that are rich and harmonious, are the ones that are most appreciated by the experts, and are the ones usually found to have been painted by the masters. Nevertheless if high color combines richness and harmony it shows a fine skill. Tone has to do with the quantity of color used in the painting, and harmony with the qualities of colors. Tone and harmony must combine to make perfect coloring.

d. Composition. If we study any great poem, drama or novel, one that is constructed with a due regard for unity, we find there is one central character or idea and that all other persons, all incidents, scenes and all the little devices that go to give reality to the conception are subordinated to the central person or idea. Unless this is done the creation lacks unity and therefore lacks force, beauty and coherence. The same facts hold true of a pic[40]ture. Every good picture is so arranged and drawn that the important idea is centralized and the parts are unified and harmonized until the whole is single in its effect. This is accomplished by what is called in the language of the painter, “composition.” Important things are recognized and lesser things subordinated to give beauty, clearness and brilliancy to the central idea. While these facts are most obvious in pictures that contain figures, it is no less true in landscapes or other pictures which contain no figures. For instance, a moonlight scene on the Hudson would have as its central idea the beauty of the light on the water and the mountains. To secure this the artist would keep down the lines of the mountains, subordinate the details in the foreground and place as the central idea in the picture the pale shimmering light from the moon whether that body be itself visible or not. Oftentimes in looking at a picture it is difficult to tell wherein its excellent composition lies, but the absence of strength and unity is unerringly felt.

e. Atmosphere and Perspective. We are all familiar with the diminished size of objects seen at a distance and realize that the apparent coming together of two parallel lines, as those of a railway track, is owing to the same cause. We know, too, that this diminishing must be shown in a picture or there is no sense of distance for the spectator. What is not so clear to us usually, is that there is as great a difference in color and the appearance of objects. The diminution of size is linear perspective and the change of color due to distance and atmospheric conditions is commonly called aerial perspective. The tendency among [41]amateurs is to paint a tree green no matter how far away from the spectator it is, while a little observation and study would show the veriest tyro that the green of a distant tree has faded till to the eye it looks a bluish gray. Moreover, outlines have faded and seem to flow into those of other objects, and all combine to give to the picture the true appearance of distance, which is what the artist seeks and the one who looks at the picture has a right to expect.

f. An Application of the Foregoing Principles. What has been said on this subject of judging a picture may be made clearer by an application to one of the pictures in Journeys. Let us take, for instance, the color plate facing page 304, in Volume VI. It is a reproduction in color of the painting in water colors, Bob and Tiny Tim, and will show what is meant by the comments above almost as well as the original painting would have done.

1. Tone and color. Are the colors in the picture bright and gay or are they subdued? What are the brightest colors? Are the colors harmonious or do they “quarrel” as they come to the eye?

Are the shades of blue and purple and lighter colors in the clothing of the various persons glaring or subdued? Do you observe any inharmony which offends the eye, or are you pleased with contrasting colors and tones? The harmony in color is due to the choice of colors that do not contrast too strongly. The artist knew which were complementary colors; that is, which, united, form white. Which colors in the picture do you think [42]show warmth, and which show cold, as suitable to out-of-door scenes? What effect on the rest of the picture does the olive green of the interior of the room have? What effect does the gray green of the open door have?

2. Light and Shade. Is the picture flat and without appearance of life, or do the persons and objects stand out in a life-like manner? Are parts of the picture in shade, so that outlines are lost? The artist has shown the left of the building in the foreground as in shadow; how is this effect produced? Do you observe gradations of tone in the shawl on Tiny Tim, which indicate relative light and shadow? Where is the highest light in the picture, and where the darkest shadow? Are the lights strong as if the sun were shining, or soft and diffused, as is noticeable on a snowy winter’s day?

3. Line. Although you cannot see Bob’s feet in the picture, do you feel that his body is well supported? Is his position natural, as of one carrying a burden on one shoulder? Are the lines of the figures in the foreground clear and distinct? How do they compare with the lines of the figures and building across the street? In both cases the artist gives us all that is necessary to convey the impression of reality. In the use of oils and water colors, sharp lines are avoided. Colors are used so that different surfaces and effects flow into one another; the lines are concealed and we have the very counterfeit of reality. This constitutes good drawing.

4. Composition. What is the central idea of the picture? The artist has brought the principal figures into the immediate foreground; do the ar[43]rangement of color, contrasts of tone values, and the smaller figures in the background give life and significance to the figures of Bob and Tiny Tim? Would the effectiveness of the picture be greater or less if the artist had failed to show the snowy outdoor scene, with its holiday spirit? Do you recall the incident in the story portrayed by the picture? Are the characteristics of Bob and Tiny Tim, as described by Dickens, faithfully followed by the artist? Do their faces show the spirit of Christmas? If you had not read the story, would you not feel a glow of sympathy for the little boy, and a wish that you could join in making a happy holiday for him? Has not the artist succeeded in bringing the scene described by the author more vividly and beautifully to us?

5. Atmosphere and Perspective. How far from the figures of Bob and the little boy are the people on the sidewalk? How does the artist express the idea of relative distance? Are there any lines in the picture which help us to determine distance? If the eye follows the lines of the cross pieces on the door, will they not come together if extended far enough to the left? Of course the buildings across the street are not very far away, but their outlines are a little hazy. Does this haziness help to give the effect of distance? Do you think the door was really a gray-green? Has the artist used this tone to show the effect of the outdoor light on a gray, or possibly a white door? The building across the street, at the left, has yellow and red and purple tones; do you think these were the actual colors? If not, why has the artist selected these particular shades? Do parts of buildings or other objects in [44]shadow take on different shades from parts in bright lights? What colors appear most frequently in the picture? Has the artist succeeded in giving the picture the atmosphere of Dickens’s story?

Pictures are in themselves a language—the oldest as well as the most universal tongue of the world. The primitive man of all races resorted to a picture-writing in his first efforts to transcribe his thoughts and emotions into a more lasting form than the oral expression. Our earliest authentic history of the customs, beliefs and life of the ancient Egyptians, the Babylonians, the Chinese and even our own American Indians comes to us from the pictured records they left on stone, wood or clay.

In the present age, what child does not yield to the magic rhythm and the compelling lilt of the old nursery rhymes! With what added joy does he discover that there are pictures for these treasured jingles! And long before the printed words can be recognized he enters the alluring world of books by “reading” the illustrations. With glowing eyes on the picture he repeats the rhyme he had learned from its many demanded repetitions.

By giving him simple, clear, realistic conceptions through pictures, we influence the child to read eagerly the text, to discover the whole story, of which such a fascinating hint is given in the portion illustrated. These first pictures must satisfy the child’s love of action and movement, and portray [45]only the most dramatic scenes, the big important facts with all superfluous happenings omitted.

In fables, where the primary purpose is to convey an abstract truth, a something bigger and broader than the mere interesting events described, the illustrations add much to the meaning and purpose of the text. Here the artist shows not only the physical attributes of the real animal, but in a subtle way goes a step further and through the features or the attitude suggests the characteristics attributed in the fable. Thus unconsciously the little reader gets from the picture an increased conception of the sly, clever, crafty ways of the fox or the slow, plodding, steadfast patience of the tortoise.

As literature develops from the simple nursery rhyme and the brief, abrupt fable to the fairy tale with its illusive beauty, so the pictures should advance in a parallel and a closely related manner. The illustrations now take on a mysterious, unreal, esthetic quality, in harmony with the world of fairy lore, and train the imagination as much as the direct words of the author. The child realizes that the forest scenes which furnish the background for so many of his favorite fairy tales have a subtle beauty which has never been seen by him. Gradually through such pictures he is led to seek an ideal beauty in the real world. He also becomes able not only to appreciate the poetic rendering of this expression of the ideal but is capable of forming more varied mental images of things about which he reads; to put more of his own individuality, his own conceptions, into his mental picture.

The passing ages have so completely revolution[46]ized the customs and ways of life that the child of today finds comparatively little in his familiar surroundings which he can link with the world of history and legend. Literature should be supplemented by pictures to bridge this chasm and to bring legendary and historical heroes into the child’s own world and enable him to follow their thoughts, interpret their emotions and appreciate their actions.

The child who sees a picture of court life where the cavalier is attired in richly colored velvet, silk, lace, and jewels, and surrounded by the luxuries of the court, and compares it with another of the same period which portrays a Puritan in his somber-hued, severe suit, stiff linen collar and cuffs, broad-brimmed, plain hat and not a single jewel or ornament used for mere decorative or esthetic value, realizes the vast difference in the types and character of the two men. He is furnished with an appropriate mental atmosphere in which to follow their history and in which to comprehend the inevitable clash that came between the Cavaliers and the Roundheads. He will then eagerly and sympathetically follow the Pilgrims in their lonely stay in Holland and in their brave struggle in the new country. Here, again, the various pictures portray a land and climate as vigorous, uncompromising and stern as the characters of the Pilgrims themselves. Then the great forests, the felling of the trees, the erection of the log houses and forts, the meeting of Puritans with the neighboring Indians, with their curious costumes, homes, customs and occupations, introduce other phases of life that put the child in a receptive mood for the [47]reading of colonial history, Indian legends and stories of pioneer life.

Familiarity with the author’s portrait, with pictures of his home or his favorite scenes, brings a something of the writer’s personality to the child. He feels the story is told more directly to him. A sympathetic bond is established that leads him to a more intimate and a more intelligent acquaintance with the author’s emotions, thoughts, style and purposes as expressed in his works. He reads Thoreau’s Journal, and notes uncomprehendingly, the potent sway of nature over the heart and life of the man. It requires the keen vision and the genius of the artist to give him a realization of the mesmeric influence nature frequently exerts.

If this author’s portrait is the work of a great artist it will perform a double service. For example, the reproduction of the Aesop of Velasquez not only gives the child an idea of the appearance of that creator of the wonderful fables, but it also introduces the great Spanish artist who has depicted marvelous interpretations of life on canvas and has so wonderfully influenced the style and method of the work of many of the artists who succeeded him.

The world of literature is filled with poems and stories which emphasize abstract truths, teach needed lessons or give universal principles of beauty. Many of these have been the subject and the inspiration of pictures. And, in the re-telling of the poem or story with brush or pen, the artists have added a something of their own individuality and character which serves not only to emphasize and perpetuate themselves through their pictured [48]translation of these noble thoughts, but also makes the principles inculcated by the author become a part of the child’s moral creed.

All have long realized the value of pictures in connection with stories involving scientific knowledge, but the co-operation of the artist with the author in presenting literature to children is of equal importance. The picture arrests the interest of the child and wins his love for books long before he can read; it arouses his desire to master the meaning of the printed forms, that he may discover the story for himself; it gives him facts regarding unfamiliar things without which knowledge the printed symbol means little; it leads him to the discovery of unseen beauties in his environment; it develops his imagination; it arouses his creative faculties; it aids him to grasp the deepest, highest meaning of the world’s literature; it opens up the undreamed beauties of the vast world of art; it interprets abstract thoughts until they become a part of his character, and CHARACTER is the true end of all READING and of all EDUCATION.

Children love pictures, and they love to make them. We of riper years are inclined to forget how very strong was our pictorial instinct when we were young. A little girl may make on a sheet of paper a few irregular lines not very well connected, wholly meaningless to us, and see in them very plainly every lineament of her favorite doll. She sees no lines, no paper, only her own precious doll.[49] A little later she will draw pictures to illustrate a story, and while we may see nothing in her work, she sees enough to make the story more real, and is in this way preparing herself to read more intelligently and with greater appreciation as she grows older. We should not laugh at these crude drawings, nor try to make them better. They express her ideas in her way, and that is enough. On the other hand, we should encourage her to try other pictures for other stories till she learns herself to distrust her drawings, or finds a way to express herself so that others may understand what she thinks and feels.

Pictures mean something, always. In the first place they show to him who can read them what some one else has thought and felt. If they are meant to illustrate something in literature, they may fail because the artist has not caught the spirit of what he is trying to depict, or because he lacks in execution. On our side, they may fail because we cannot interpret his work, either from lack of understanding or from the dullness of our sensibilities. Again, we may object to the artist’s interpretation of the literature, and his pictures may merely excite our opposition. Usually, however, we see through the artist’s eyes from a new point of view, so that, even if we do not altogether approve what we see, we are led to question and find for ourselves something new, pleasing and helpful.

Children are harsh critics, not only of pictures but of literature itself, and the critical spirit is a good one to cultivate, if it is not allowed to fall into captious fault-finding. On the whole, however, it is far better to point out the good things [50]in a picture than to call attention to poor execution or poor conception. Leave criticism generally to those infrequent cases in which the artist has actually blundered because he has not read the selection closely or accurately, or has been careless in the things he ought to know. For instance, it would be absurd to show King Arthur in a modern dress suit, or to put fire-arms in the hands of the Indians who met Columbus for the first time. But such faults occur infrequently. Usually the pictures are careful studies, and give many a hint on costuming, manners and customs, as well as on the proper surroundings of the characters.

Some selections are so universal in their nature, so freely applicable to all times and places, that the artist may be allowed to delineate any people, anywhere, at any time. Nursery rhymes, so often alluded to, lend themselves to an endless variety of imaginary people and places. The old woman might be living still in her shoe and whipping her children soundly, in a twentieth-century wrapper, or clothed in skins she might send them supperless to bed in pre-historic ages. Whether Jack and Jill wore wooden shoes or patent-leather pumps we shall never really know; perhaps their little feet were encased in moccasins, or they may have been bare and ornamented with rings: what we do know is that Jack broke his crown and Jill came tumbling after.

So we will give the artists all the latitude they wish, as long as they keep the facts straight, and we will try to help the children to see what the artist saw, and so get clearer visions for themselves.

The pictures in these books are from many artists, [51]all of whom have given an interpretation of the selection they were working upon, and have given it in such a way as to be helpful and inspiring to their youthful readers. Every time the artists have tried to get a child’s view of things and to draw so that a child will like their work. Their enthusiasm has been boundless, and their execution remarkably good. Some of their pictures are gay, some are grave, a few sad; some are highly imaginative and others very realistic. Not a few are wonderfully beautiful. Among so many designs, so many kinds, everyone will find something to admire.