[p1]

A

CATHEDRAL COURTSHIP

She

Winchester,

May 28, ——,

The Royal Garden Inn.

We are doing the English cathedral towns, Aunt Celia and I. Aunt Celia has an intense desire to improve my mind. Papa told her, when we were leaving Cedarhurst, that he wouldn’t for the world have it too much improved, and Aunt Celia remarked that, so far as she could judge, there was no immediate danger; with which exchange of hostilities they parted.

We are travelling under the yoke of an [p2] iron itinerary, warranted neither to bend nor break. It was made out by a young High Church curate in New York, and if it were a creed, or a document that had been blessed by all the bishops and popes, it could not be more sacred to Aunt Celia. She is awfully High Church, and I believe she thinks this tour of the cathedrals will give me a taste for ritual and bring me into the true fold. Mamma was a Unitarian, and so when she was alive I generally attended service at that church. Aunt Celia says it is not a Church; that the most you can say for it is that it is a ‘belief’ rather loosely and carelessly formulated. She also says that dear old Dr. Kyle is the most dangerous Unitarian she knows, because he has leanings towards Christianity.

Long ago, in her youth, Aunt Celia was engaged to a young architect. He, with his triangles and T-squares and things, [p3] succeeded in making an imaginary scale-drawing of her heart (up to that time a virgin forest, an unmapped territory), which enabled him to enter in and set up a pedestal there, on which he has remained ever since. He has been only a memory for many years, to be sure, for he died at the age of twenty-six, before he had had time to build anything but a livery stable and a country hotel. This is fortunate, on the whole, because Aunt Celia thinks he was destined to establish American architecture on a higher plane, rid it of its base, time-serving, imitative instincts, and waft it to a height where, in the course of centuries, it would have been revered and followed by all the nations of the earth.

I went to see the stable, after one of these Miriam-like flights of prophecy on the might-have-been. It isn’t fair to judge a man’s promise by one modest performance, [p4] and so I shall say nothing, save that I am sure it was the charm of the man that won my aunt’s affection, not the genius of the builder.

This sentiment about architecture and this fondness for the very toppingest High Church ritual cause Aunt Celia to look on the English cathedrals with solemnity and reverential awe. She has given me a fat note-book, with ‘Katharine Schuyler’ stamped in gold letters on the Russia-leather cover, and a lock and key to conceal its youthful inanities from the general public. I am not at all the sort of girl who makes notes, and I have told her so; but she says that I must at least record my passing impressions, if they are ever so trivial and commonplace. She also says that one’s language gains unconsciously in dignity and sobriety by being set down in black and white, and that a liberal use of pen and ink will [p5] be sure to chasten my extravagances of style.

I wanted to go directly from Southampton to London with the Abbotts, our ship friends, who left us yesterday. Roderick Abbott and I had had a charming time on board ship (more charming than Aunt Celia knows, because she was very ill, and her natural powers of chaperoning were severely impaired), and the prospect of seeing London sights together was not unpleasing; but Roderick Abbott is not in Aunt Celia’s itinerary, which reads: ‘Winchester, Salisbury, Bath, Wells, Gloucester, Oxford, London, Ely, Peterborough, Lincoln, York, Durham.’ These are the cathedrals Aunt Celia’s curate chose to visit, and this is the order in which he chose to visit them. Canterbury was too far east for him, and Exeter was too far west, but he suggests Ripon and Hereford if strength and time permit.

[p6]

Aunt Celia is one of those persons who

are born to command, and when they are

thrown in contact with those who are born

to be commanded all goes as merry as a

marriage bell; otherwise not.

So here we are at Winchester; and I don’t mind all the Roderick Abbotts in the universe, now that I have seen the Royal Garden Inn, its pretty coffee-room opening into the old-fashioned garden, with its borders of clove-pinks, its aviaries, and its blossoming horse-chestnuts, great towering masses of pink bloom.

Aunt Celia has driven to St. Cross Hospital with Mrs. Benedict, an estimable lady tourist whom she ‘picked up’ en route from Southampton. I am tired, and stayed at home. I cannot write letters, because Aunt Celia has the guide-books, so I sit by the window in indolent content, watching the dear little school laddies, with their short jackets and wide white [p7] collars; they all look so jolly, and rosy, and clean, and kissable. I should like to kiss the chambermaid, too. She has a pink print dress, no fringe, thank goodness (it’s curious our servants can’t leave that deformity to the upper classes), but shining brown hair, plump figure, soft voice, and a most engaging way of saying ‘Yes, miss? Anythink more, miss?’ I long to ask her to sit down comfortably and be English while I study her as a type, but of course I mustn’t. Sometimes I wish I could retire from the world for a season and do what I like, ‘surrounded by the general comfort of being thought mad.’

An elegant, irreproachable, high-minded model of dignity and reserve has just knocked and inquired what we will have for dinner. It is very embarrassing to give orders to a person who looks like a Justice of the Supreme Court, but I said languidly:

‘How would you like a clear soup, a good spring soup, to begin with, miss?’

‘Very much.’

‘And a bit of turbot next, miss, with anchovy sauce?’

‘Yes, turbot, by all means,’ I said, my mouth watering at the word.

‘And what else, miss? Would you enjoy a young duckling, miss, with new potatoes and green peas?’

‘Just the thing; and for dessert—’ I couldn’t think what I ought to order next in England, but the high-minded model coughed apologetically, and, correcting my language, said:

‘I was thinking you might like gooseberry-tart and cream for a sweet, miss.’

Oh that I could have vented my New World enthusiasm in a sigh of delight as I heard those intoxicating words, heretofore met only in English novels!

[p9]

‘Ye—es,’ I said hesitatingly, though I

was palpitating with joy, ‘I fancy we

should like gooseberry-tart’ (here a bright

idea entered my mind); ‘and perhaps, in

case my aunt doesn’t care for the gooseberry-tart,

you might bring a lemon-squash,

please.’

Now, I had never met a lemon-squash personally, but I had often heard of it, and wished to show my familiarity with British culinary art.

‘It would ’ardly be a substitute for gooseberry-tart, miss; but shall I bring one lemon-squash, miss?’

‘Oh, as to that, it doesn’t matter,’ I said haughtily; ‘bring a sufficient number for two persons.’

* * * * *

Aunt Celia came home in the highest feather. She had twice been mistaken for an Englishwoman. She said she thought [p10] that lemon-squash was a drink; I thought, of course, it was a pie; but we shall find out at dinner, for, as I said, I ordered a sufficient number for two persons, and the head-waiter is not a personage who will let Transatlantic ignorance remain uninstructed.

At four o’clock we attended evensong at the cathedral. I shall not say what I felt when the white-surpliced boy choir entered, winding down those vaulted aisles, or when I heard for the first time that intoned service, with all its ‘witchcraft of harmonic sound.’ I sat quite by myself in a high carved oak seat, and the hour was passed in a trance of serene delight. I do not have many opinions, it is true, but papa says I am always strong on sentiments; nevertheless, I shall not attempt to tell even what I feel in these new and beautiful experiences, for it has been better told a thousand times.

[p12]

There were a great many people at

service, and a large number of Americans

among them, I should think, though we

saw no familiar faces. There was one

particularly nice young man, who looked

like a Bostonian. He sat opposite me.

He didn’t stare—he was too well bred,

but when I looked the other way he looked

at me. Of course, I could feel his eyes;

anybody can—at least, any girl can; but

I attended to every word of the service,

and was as good as an angel. When the

procession had filed out, and the last

strain of the great organ had rumbled into

silence, we went on a tour through the

cathedral, a heterogeneous band, headed

by a conscientious old verger, who did his

best to enlighten us, and succeeded in

virtually spoiling my pleasure.

After we had finished (think of ‘finishing’ a cathedral in an hour or two!), Aunt Celia and I, with one or two others, [p13] wandered through the beautiful close, looking at the exterior from every possible point, and coming at last to a certain ruined arch which is very famous. It did not strike me as being remarkable. I could make any number of them with a pattern without the least effort. But, at any rate, when told by the verger to gaze upon the beauties of this wonderful relic and tremble, we were obliged to gaze also upon the beauties of the aforesaid nice young man, who was sketching it.

As we turned to go away, Aunt Celia dropped her bag. It is one of those detestable, all-absorbing, all-devouring, thoroughly respectable, but never proud, Boston bags, made of black cloth with leather trimmings, ‘C. Van T.’ embroidered on the side, and the top drawn up with stout cords which pass over the Boston wrist or arm. As for me, I loathe them, and would not for worlds be seen carrying [p14] one, though I do slip a great many necessaries into Aunt Celia’s.

I hastened to pick up the horrid thing, for fear the nice young man would feel obliged to do it for me; but, in my indecorous haste, I caught hold of the wrong end, and emptied the entire contents on the stone flagging. Aunt Celia didn’t notice; she had turned with the verger, lest she should miss a single word of his inspired testimony. So we scrambled up the articles together, the nice young man and I; and oh, I hope I may never look upon his face again.

There were prayer-books and guide-books, a Bath bun, a bottle of soda-mint tablets, a church calendar, a bit of gray frizz that Aunt Celia pins into her cap when she is travelling in damp weather, a spectacle-case, a brandy-flask, and a bon-bon-box, which broke and scattered cloves and peppermint lozenges. (I hope he [p15] guessed Aunt Celia is a dyspeptic, and not intemperate!) All this was hopelessly vulgar, but I wouldn’t have minded anything if there had not been a Duchess novel. Of course he thought that it belonged to me. He couldn’t have known Aunt Celia was carrying it for that accidental Mrs. Benedict, with whom she went to St. Cross Hospital.

After scooping the cloves out of the cracks in the stone flagging—and, of course, he needn’t have done this, unless he had an abnormal sense of humour—he handed me the tattered, disreputable-looking copy of ‘A Modern Circe,’ with a bow that wouldn’t have disgraced a Chesterfield, and then went back to his easel, while I fled after Aunt Celia and her verger.

* * * * *

Memoranda: The Winchester Cathedral has the longest nave. The inside is more [p16] superb than the outside. Izaak Walton and Jane Austen are buried here.

He

Winchester,

May 28,

The White Swan.

As sure as my name is Jack Copley, I saw the prettiest girl in the world to-day—an American, too, or I am greatly mistaken. It was in the cathedral, where I have been sketching for several days. I was sitting at the end of a bench, at afternoon service, when two ladies entered by the side-door. The ancient maiden, evidently the head of the family, settled herself devoutly, and the young one stole off by herself to one of the old carved seats back of the choir. She was worse than pretty! I made a memorandum of her during service, as she sat under the dark carved-oak canopy, with this Latin inscription over her head:

[p17]

Carlton cum

Dolby

Letania

IX Solidorum

Super Flumina

Confitebor tibi

Dūc probati

There ought to be a law against a woman’s making a picture of herself, unless she is willing to allow an artist to ‘fix her’ properly in his gallery of types.

A black-and-white sketch doesn’t give any definite idea of this charmer’s charms, but sometime I’ll fill it in—hair, sweet little hat, gown, and eyes, all in golden brown, a cape of tawny sable slipping off her arm, a knot of yellow primroses in her girdle, carved-oak background, and the afternoon sun coming through a stained-glass window. Great Jove! She had a most curious effect on me, that girl! I can’t explain it—very curious, altogether new, and rather pleasant. When one of [p18] the choir-boys sang ‘Oh for the wings of a dove!’ a tear rolled out of one of her lovely eyes and down her smooth brown cheek. I would have given a large portion of my modest monthly income for the felicity of wiping away that teardrop with one of my new handkerchiefs, marked with a tremendous ‘C’ by my pretty sister.

An hour or two later they appeared again—the dragon, who answers to the name of ‘Aunt Celia,’ and the ‘nut-brown mayde,’ who comes when she is called ‘Katharine.’ I was sketching a ruined arch. The dragon dropped her unmistakably Boston bag. I expected to see encyclopædias and Russian tracts fall from it, but was disappointed. The ‘nut-brown mayde’ (who has been trained in the way she should go) hastened to pick up the bag for fear that I, a stranger, should serve her by doing it. She was punished by turning it inside out, and I [p19] was rewarded by helping her gather together the articles, which were many and ill-assorted. My little romance received the first blow when I found that she reads the Duchess novels. I think, however, she has the grace to be ashamed of it, for she blushed scarlet when I handed her ‘A Modern Circe.’ I could have told her that such a blush on such a cheek would almost atone for not being able to read at all, but I refrained. It is vexatious all the same, for, though one doesn’t expect to find perfection here below, the ‘nut-brown mayde,’ externally considered, comes perilously near it. After she had gone I discovered a slip of paper which had blown under some stones. It proved to be an itinerary. I didn’t return it. I thought they must know which way they were going; and as this was precisely what I wanted to know, I kept it for my own use. She is doing the cathedral towns. I am doing the [p20] cathedral towns. Happy thought! Why shouldn’t we do them together—we and Aunt Celia? A fellow whose mother and sister are in America must have some feminine society!

I had only ten minutes to catch my train for Salisbury, but I concluded to run in and glance at the registers of the principal hotels. Found my ‘nut-brown mayde’ at once in the guest-book of the Royal Garden Inn: ‘Miss Celia Van Tyck, Beverly, Mass., U.S.A. Miss Katharine Schuyler, New York, U.S.A.’ I concluded to stay over another train, ordered dinner, and took an altogether indefensible and inconsistent pleasure in writing ‘John Quincy Copley, Cambridge, Mass.,’ directly beneath the charmer’s autograph.

* * * * *

[p21]

She

Salisbury,

June 1,

The White Hart Inn.

We left Winchester on the 1.16 train yesterday, and here we are within sight of another superb and ancient pile of stone. I wanted so much to stop at the Highflyer Inn in Lark Lane, but Aunt Celia said that if we were destitute of personal dignity, we at least owed something to our ancestors. Aunt Celia has a temperamental distrust of joy as something dangerous and ensnaring. She doesn’t realize what fun it would be to date one’s letters from the Highflyer Inn, Lark Lane, even if one were obliged to consort with poachers and trippers in order to do it.

Better times are coming, however, for she was in a melting mood last evening, and promised me that wherever I can find an inn with a picturesque and unusual [p22] name, she will stop there, provided it is clean and respectable, if I on my part will agree to make regular notes of travel in my Russia-leather book. She says that ever since she was my age she has asked herself nightly the questions Pythagoras was in the habit of using as a nightcap:

I asked her why Pythagoras didn’t say ‘runned’ and make a consistent rhyme, and she evaded the point by answering that Pythagoras didn’t write it in English.

We attended service at three. The music was lovely, and there were beautiful stained-glass windows by Burne-Jones and Morris. The verger (when wound up with a shilling) talked like an electric doll. If that nice young man is making a cathedral tour like ourselves, he isn’t [p23] taking our route, for he isn’t here. If he has come over for the purpose of sketching, he wouldn’t stop with one cathedral, unless he is very indolent and unambitious, and he doesn’t look either of these.

Perhaps he began at the other end, and worked down to Winchester. Yes, that must be it, for the Ems sailed yesterday from Southampton. Too bad, for he was a distinct addition to the landscape. Why didn’t I say, when he was picking up the collection of curios in Aunt Celia’s bag, ‘You needn’t bother about the novel, thank you; it is not mine, and anyway it would be of no use to anybody.’

June 2.

We intended to go to Stonehenge this morning, but it rained, so we took a ‘growler’ and went to the Earl of Pembroke’s country place to see the pictures. Had a delightful morning with the [p24] magnificent antiques, curios, and portraits. The Van Dyck room is a joy for ever; but one really needs a guide or a friend who knows something of art if one would understand these things. There were other visitors; nobody who looked especially interesting. Don’t like Salisbury so well as Winchester. Don’t know why. We shall drive this afternoon, if it is fair, and go to Bath and Wells to-morrow, I am glad to say. Must read Baedeker on the Bishop’s palace. Oh, dear! if one could only have a good time and not try to know anything!

Memoranda: This cathedral has the highest spire. Remember: Winchester, longest nave; Salisbury, highest spire.

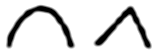

The Lancet style is those curved lines

meeting in a rounding or a sharp point like

this  , and then joined together like

this

, and then joined together like

this  , the way they scallop

babies’ flannel petticoats. Gothic looks like

triangles meeting together in various spots

[p25]

and joined with a beautiful sort of ornamented

knobs. I think I recognise Gothic

when I see it. Then there is Norman,

Early English, fully developed Early

English, Early and Late Perpendicular,

Transition, and, for aught I know, a lot of

others. Aunt Celia can tell them all apart.

, the way they scallop

babies’ flannel petticoats. Gothic looks like

triangles meeting together in various spots

[p25]

and joined with a beautiful sort of ornamented

knobs. I think I recognise Gothic

when I see it. Then there is Norman,

Early English, fully developed Early

English, Early and Late Perpendicular,

Transition, and, for aught I know, a lot of

others. Aunt Celia can tell them all apart.

He

Salisbury,

June 3,

The Red Lion.

I went off on a long tramp this afternoon, and coming on a pretty river flowing through green meadows, with a fringe of trees on either side, I sat down to make a sketch. I heard feminine voices in the vicinity, but as these are generally a part of the landscape in the tourist season, I paid no special notice. Suddenly a dainty patent-leather shoe floated towards me on the surface of the stream. It evidently had just dropped in, for it was right side [p26] up with care, and was disporting itself most merrily. ‘Did ever Jove’s tree drop such fruit?’ I quoted as I fished it out on my stick; and just then I heard a distressed voice saying, ‘Oh, Aunt Celia, I’ve lost my smart little London shoe. I was sitting in a tree taking a pebble out of the heel, when I saw a caterpillar, and I dropped it into the river—the shoe, you know, not the caterpillar.’

Hereupon she came in sight, and I witnessed the somewhat unusual spectacle of my ‘nut-brown mayde’ hopping, like a divine stork, on one foot, and ever and anon emitting a feminine shriek as the other, clad in a delicate silk stocking, came in contact with the ground. I rose quickly, and, polishing the patent leather ostentatiously inside and out with my handkerchief, I offered it to her with distinguished grace. She sat hurriedly down on the ground with as much dignity as possible, and then, [p28] recognising me as the person who picked up the contents of Aunt Celia’s bag, she said, dimpling in the most distracting manner (that’s another thing there ought to be a law against): ‘Thank you again; you seem to be a sort of knight-errant.’

‘Shall I—assist you?’ I asked. I might have known that this was going too far. Of course I didn’t suppose she would let me help her put the shoe on, but I thought—upon my soul, I don’t know what I thought, for she was about a million times prettier to-day than yesterday.

‘No, thank you,’ she said, with polar frigidity. ‘Good-afternoon.’ And she hopped back to her Aunt Celia without another word.

I don’t know how to approach Aunt Celia. She is formidable. By a curious accident of feature, for which she is not in the least responsible, she always wears an unfortunate expression as of one [p29] perceiving some offensive odour in the immediate vicinity. This may be a mere accident of high birth. It is the kind of nose often seen in the ‘first families,’ and her name betrays the fact that she is of good old Knickerbocker origin. We go to Wells to-morrow—at least, I think we do.

She

Salisbury, June 3.

I didn’t like Salisbury at first, but I find it is the sort of place that grows on one the longer one stays in it. I am quite sorry we must leave so soon, but Aunt Celia is always in haste to be gone. Bath may be interesting, but it is entirely out of the beaten path from here.

She

Bath,

June 7,

The Best Hotel.

I met him at Wells and again this [p30] afternoon here. We are always being ridiculous, and he is always rescuing us. Aunt Celia never really sees him, and thus never recognises him when he appears again, always as the flower of chivalry and guardian of ladies in distress. I will never again travel abroad without a man, even if I have to hire one from a feeble-minded asylum. We work like galley-slaves, Aunt Celia and I, finding out about trains and things. Neither of us can understand Bradshaw, and I can’t even grapple with the lesser intricacies of the A B C Railway Guide. The trains, so far as I can see, always arrive before they go out, and I can never tell whether to read up the page or down. It is certainly very queer that the stupidest man that breathes, one that barely escapes idiocy, can disentangle a railway guide when the brightest woman fails. Even the boots at the inn in Wells took my book, and, rubbing his frightfully [p31] dirty finger down the row of puzzling figures, found the place in a minute, and said, ‘There ye are, miss.’ It is very humiliating. I suppose there are Bradshaw professorships in the English universities, but the boots cannot have imbibed his knowledge there. A traveller at table d’hôte dinner yesterday said there are three classes of Bradshaw trains in Great Britain: those that depart and never arrive, those that arrive but never depart, and those that can be caught in transit, going on, like the wheel of eternity, with neither beginning nor end. All the time I have left from the study of routes and hotels I spend on guide-books. Now, I’m sure that if any one of the men I know were here, he could tell me all that is necessary as we walk along the streets. I don’t say it in a frivolous or sentimental spirit in the least, but I do affirm that there is hardly any juncture in life where one isn’t better [p32] off for having a man about. I should never dare divulge this to Aunt Celia, for she doesn’t think men very nice. She excludes them from conversation as if they were indelicate subjects.

But to go on, we were standing at the door of Ye Crowne and Keys at Wells, waiting for the fly which we had ordered to take us to the station, when who should drive up in a four-wheeler but the flower of chivalry. Aunt Celia was saying very audibly, ‘We shall certainly miss the train, if the man doesn’t come at once.’

‘Pray take this cab,’ said the flower of chivalry. ‘I am not leaving for an hour or more.’

Aunt Celia got in without a murmur; I sneaked in after her, not daring to lift my eyes. I don’t think she looked at him, though she did vouchsafe the remark that he seemed to be a civil sort of person.

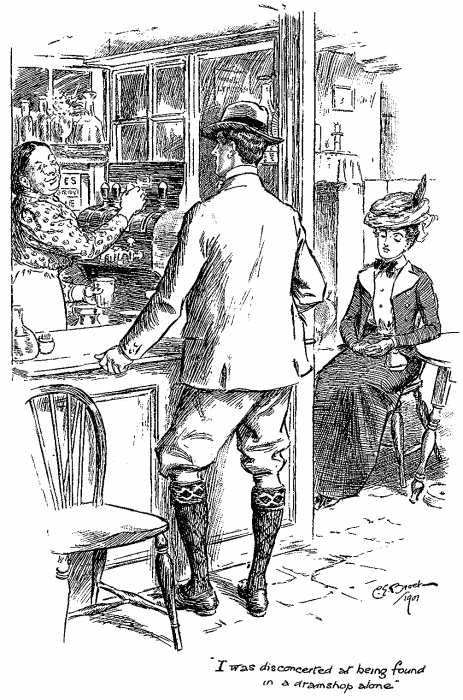

I was walking about by myself this [p33] afternoon. Aunt Celia and I had taken a long drive, and she had dropped me in a quaint old part of the town that I might have a brisk walk home for exercise. Suddenly it began to rain, which it is apt to do in England, between the showers, and at the same moment I espied a sign, ‘Martha Huggins, Licensed Victualler.’ It was a nice, tidy little shop, with a fire on the hearth and flowers in the window, and I thought no one would catch me if I stepped inside to chat with Martha until the sun shone again. I fancied it would be delightful and Dickensy to talk quietly with a licensed victualler by the name of Martha Huggins.

Just after I had settled myself, the flower of chivalry came in and ordered ale. I was disconcerted at being found in a dramshop alone, for I thought, after the bag episode, he might fancy us a family of inebriates. But he didn’t evince the [p34] slightest astonishment; he merely lifted his hat, and walked out after he had finished his ale. He certainly has the loveliest manners, and his hair is a more beautiful colour every time I see him.

And so it goes on, and we never get any further. I like his politeness and his evident feeling that I can’t be flirted and talked with like a forward boarding-school miss; but I must say I don’t think much of his ingenuity. Of course one can’t have all the virtues, but if I were he, I would part with my distinguished air, my charming ease—in fact, almost anything, if I could have in exchange a few grains of common-sense, just enough to guide me in the practical affairs of life.

I wonder what he is? He might be an artist, but he doesn’t seem quite like an artist; or just a dilettante, but he doesn’t look in the least like a dilettante. Or he might be an architect; I think that is the [p36] most probable guess of all. Perhaps he is only ‘going to be’ one of these things, for he can’t be more than twenty-five or twenty-six. Still, he looks as if he were something already; that is, he has a kind of self-reliance in his mien—not self-assertion, nor self-esteem, but belief in self, as if he were able, and knew that he was able, to conquer circumstances.

Aunt Celia wouldn’t stay at Ye Olde Bell and Horns here. She looked under the bed (which, I insist, was an unfair test), and ordered her luggage to be taken instantly to the Grand Pump Room Hotel.

Memoranda: Bath became distinguished for its architecture and popular as a fashionable resort in the 17th century from the deserved repute of its waters and through the genius of two men, Wood the architect and Beau Nash, Master of Ceremonies. A true picture of the society of the period is found in Smollett’s ‘Humphry Clinker’, [p37] which Aunt Celia says she will read and tell me what is necessary. Remember the window of the seven lights in the Abbey Church, the one with the angels ascending and descending; also the rich Perp. chantry of Prior Bird, S. of chancel. It is Murray who calls it a Perp. chantry, not I.

She

June 8.

It was very wet this morning, and I had breakfast in my room. The maid’s name is Hetty Precious, and I could eat almost anything brought me by such a beautifully named person. A little parcel postmarked Bath was on my tray, but as the address was printed, I have no clue to the sender. It was a wee copy of Jane Austen’s ‘Persuasion,’ which I have read before, but was glad to see again, because I had forgotten that the scene is partly laid in Bath, [p38] and now I can follow dear Anne and vain Sir Walter, hateful Elizabeth and scheming Mrs. Clay through Camden Place and Bath Street, Union Street, Milsom Street, and the Pump Yard. I can even follow them to the site of the White Hart Hotel, where the adorable Captain Wentworth wrote the letter to Anne. After more than two hundred pages of suspense, with what joy and relief did I read that letter! I wonder if Anne herself was any more excited than I?

At first I thought Roderick Abbott sent the book, until I remembered that his literary taste is Puck in America and Pick-me-up and Tit-Bits in England; and now I don’t know what to think. I turned to Captain Wentworth’s letter in the last chapter but one—oh, it is a beautiful letter! I wish somebody would ever write me that he is ‘half agony, half hope,’ and that I ‘pierce his soul.’ Of course, it [p39] would be wicked to pierce a soul, and of course they wouldn’t write that way nowadays; but there is something perfectly delightful about the expression.

Well, when I found the place, what do you suppose? Some of the sentences in the letter seem to be underlined ever so faintly; so faintly, indeed, that I cannot quite decide whether it’s my imagination or a lead-pencil, but this is the way it seems to look:

‘I can listen no longer in silence. I must speak to you by such means as are within my reach. You pierce my soul. I am half agony, half hope. Tell me not that I am too late, that such precious feelings are gone for ever. I offer myself to you again with a heart even more your own than when you almost broke it, eight years and a half ago. Dare not say that man forgets sooner than woman, that his love has an earlier death. I have loved [p40] none but you. Unjust I may have been, weak and resentful I have been, but never inconstant. You alone have brought me to Bath. For you alone, I think and plan. Have you not seen this? Can you fail to have understood my wishes? I had not waited even these ten days, could I have read your feelings, as I think you must have penetrated mine. I can hardly write. I am every instant hearing something which overpowers me. You sink your voice, but I can distinguish the tones of that voice when they would be lost on others. Too good, too excellent creature! You do us justice indeed. You do believe that there is true attachment and constancy among men. Believe it to be most fervent, most undeviating, in

‘F. W.’

Of course, this means nothing. Somebody has been reading the book, and [p41] marked it idly as he (or she) read. I can imagine someone’s underlining a splendid sentiment like ‘Dare not say that man forgets sooner than woman!’ but why should a reader lay stress on such a simple sentence as ‘You alone brought me to Bath’?

He

Gloucester,

June 10,

The Golden Slipper.

Nothing accomplished yet. Her aunt is a Van Tyck, and a stiff one, too. I am a Copley, and that delays matters. Much depends upon the manner of approach. A false move would be fatal. We have seven more towns (as per itinerary), and if their thirst for cathedrals isn’t slaked when these are finished, we have the entire Continent to do. If I could only succeed in making an impression on the retina of Aunt Celia’s eye! Though I have been under her feet for ten days, she never yet [p42] has observed me. This absent-mindedness of hers serves me ill now, but it may prove a blessing later on.

I made two modest moves on the chessboard of Fate yesterday, but they were so very modest and mysterious that I almost fear they were never noticed.

She

Gloucester,

June 10,

In Impossible Lodgings chosen by Me.

Something else awfully exciting has happened.

When we walked down the railway platform at Bath, I saw a pink placard pasted on the window of a first-class carriage. It had ‘VAN TYCK: RESERVED,’ written on it, after the English fashion, and we took our places without question. Presently Aunt Celia’s eyes and mine alighted at the same moment on a bunch of yellow primroses [p43] pinned on the stuffed back of the most comfortable seat next the window.

‘They do things so well in England,’ said Aunt Celia admiringly. ‘The landlord must have sent my name to the guard—you see the advantage of stopping at the best hotels, Katharine—but one would not have suspected him capable of such a refined attention as the bunch of flowers. You must take a few of them, dear; you are so fond of primroses.’

Oh! I am having a delicious time abroad! I do think England is the most interesting country in the world; and as for the cathedral towns, how can anyone bear to live anywhere else?

She

Oxford,

June 12,

The Mitre.

It was here in Oxford that a grain of common-sense entered the brain of the [p44] flower of chivalry; you might call it the dawn of reason. We had spent part of the morning in High Street, ‘the noblest old street in England,’ as our dear Hawthorne calls it. As Wordsworth had written a sonnet about it, Aunt Celia was armed for the fray—a volume of Wordsworth in one hand, and one of Hawthorne in the other. (I wish Baedeker and Murray didn’t give such full information about what one ought to read before one can approach these places in a proper spirit.) When we had done High Street, we went to Magdalen College, and sat down on a bench in Addison’s Walk, where Aunt Celia proceeded to store my mind with the principal facts of Addison’s career, and his influence on the literature of the something or other century. The cramming process over, we wandered along, and came upon ‘him’ sketching a shady corner of the walk.

[p45]

Aunt Celia went up behind him, and,

Van Tyck though she is, she could not

restrain her admiration of his work. I

was surprised myself; I didn’t suppose so

good-looking a youth could do such good

work. I retired to a safe distance, and

they chatted together. He offered her

the sketch; she refused to take advantage

of his kindness. He said he would ‘dash

off’ another that evening and bring it to

our hotel—‘so glad to do anything for a

fellow-countryman,’ etc. I peeped from

behind a tree and saw him give her his

card. It was an awful moment; I trembled,

but she read it with unmistakable approval,

and gave him her own with an expression

that meant, ‘Yours is good, but beat that

if you can!’

She called to me, and I appeared. Mr. John Quincy Copley, Cambridge, was presented to her niece, Miss Katharine Schuyler, New York. It was over, and a [p46] very small thing to take so long about, too.

He is an architect, and, of course, has a smooth path into Aunt Celia’s affections. Theological students, ministers, missionaries, heroes, and martyrs she may distrust, but architects never!

‘He is an architect, my dear Katharine, and he is a Copley,’ she told me afterwards. ‘I never knew a Copley who was not respectable, and many of them have been more.’

After the introduction was over, Aunt Celia asked him guilelessly if he had visited any other of the English cathedrals. Any others, indeed!—this to a youth who had been all but in her lap for a fortnight. It was a blow, but he rallied bravely, and, with an amused look in my direction, replied discreetly that he had visited most of them at one time or another. I refused to let him see that I had ever noticed him before—that is, particularly.

[p47]

I wish I had had an opportunity of

talking to him of our plans, but just as I

was leading the conversation into the

proper channels, the waiter came in for

breakfast orders—as if it mattered what

one had for breakfast, or whether one had

any at all. I can understand an interest

in dinner or even in luncheon, but not in

breakfast; at least not when more important

things are under consideration.

* * * * *

Memoranda: ‘The very stones and mortar of this historic town seem impregnated with the spirit of restful antiquity.’ (Extract from one of Aunt Celia’s letters.) Among the great men who have studied here are the Prince of Wales, Duke of Wellington, Gladstone, Sir Robert Peel, Sir Philip Sidney, William Penn, John Locke, the two Wesleys, Ruskin, Ben Jonson, and Thomas Otway. (Look Otway up.)

[p48]

He

Oxford,

June 13,

The Angel.

I have done it, and if I hadn’t been a fool and a coward I might have done it a week ago, and spared myself a good deal of delicious torment. ‘How sweet must be Love’s self possessed, when but Love’s shadows are so rich in joy!’ or something of that sort.

I have just given two hours to a sketch of Addison’s Walk, and carried it to Aunt Celia at the Mitre. Object, to find out whether they make a long stay in London (our next point), and, if so, where. It seems they stop only a night. I said in the course of conversation:

‘So Miss Schuyler is willing to forego a London season? Marvellous self-denial!’

‘My niece did not come to Europe for a London season,’ replied Miss Van Tyck. ‘We go through London this time merely as [p49] a cathedral town, simply because it chances to be where it is geographically. We shall visit St. Paul’s and Westminster Abbey, and then go directly on, that our chain of impressions may have absolute continuity and be free from any disturbing elements.’

Oh, but she is lovely, is Aunt Celia! London a cathedral town!

Now, for my part, I should like to drop St. Paul’s for once, and omit Westminster Abbey for the moment, and sit on the top of a bus with Miss Schuyler or in a hansom jogging up and down Piccadilly. The hansom should have bouquets of paper-flowers in the windows, and the horse should wear carnations in his headstall, and Miss Schuyler should ask me questions, to which I should always know the right answers. This would be but a prelude, for I should wish later to ask her questions to which I should hope she would also know the right answers.

[p50]

Heigho! I didn’t suppose that anything

could be lovelier than that girl’s smile, but

there is, and it is her voice.

I shall call there again to-morrow morning. I don’t know on what pretext, but I shall call, for my visit was curtailed this evening by the entrance of the waiter, who asked what they would have for breakfast. Miss Van Tyck said she would be disengaged in a moment, so naturally I departed, with a longing to knock the impudent waiter’s head against the uncomprehending wall. Breakfast indeed! A fellow can breakfast regularly, and yet be in a starving condition.

He

Oxford,

June 14,

The Angel.

I have just called. They have gone! Gone hours before they intended! How shall I find her in London?

[p51]

He

London,

June 15,

Walsingham House Hotel.

As a cathedral town London leaves much to be desired. There are too many hotels, too many people, and the distances are too great. For ten hours I kept a hansom galloping between St. Paul’s and Westminster Abbey, with no result. I am now going to Ely, where I shall stay in the cathedral from morning till night, and have my meals brought to me on a tray by the verger.

She

Ely,

June 15,

At Miss Kettlestring’s lodgings.

I have lost him! He was not at St. Paul’s or Westminster in London—great, cruel, busy, brutal London, that could swallow up any precious thing and make [p52] no sign. And he is not here! They say it is a very fine cathedral.

Memoranda: The Octagon is perhaps the most beautiful and original design to be found in the whole range of Gothic architecture. Remember also the retrochoir. The lower tier of windows consists of three long lancets, with groups of Purbeck shafts at the angles; the upper, of five lancets, diminishing from the centre, and set back, as in the clerestory, within an arcade supported by shafts. (I don’t believe even he could make head or tail of this.) Remember the curious bosses under the brackets of the stone altar in the Alcock Chapel. They represent ammonites projecting from their shells and biting each other. (If I were an ammonite I know I should bite Aunt Celia. Look up ammonite.)

[p53]

He

Ely,

June 18,

The Lamb Hotel.

I cannot find her! Am racked with rheumatic pains sitting in this big, empty, solitary, hollow, reverberating, damp, desolate, deserted cathedral hour after hour. On to Peterborough this evening.

She

Peterborough, June 18.

He is not here. The cathedral, even the celebrated west front, seems to me somewhat overrated. Catherine of Aragon (or one of those Henry the Eighth wives) is buried here, also Mary Queen of Scots; but I am tired of looking at graves, viciously tired, too, of writing in this trumpery note-book. We move on this afternoon.

[p54]

He

Peterborough, June 19.

A few more days of this modern Love Chase will unfit me for professional work. Tried to draw the roof of the choir, a good specimen of early Perp., and failed. Studied the itinerary again to see if it had any unsuspected suggestions in cipher. No go! York and Durham were double-starred by the Aunt Celia’s curate as places for long stops. Perhaps we shall meet again there.

Lincoln,

June 22,

The Black Boy Inn.

I am stopping at a beastly little hole, which has the one merit of being opposite Miss Schuyler’s lodgings, for I have found her at last. My sketch-book has deteriorated in artistic value during the last two weeks. Many of its pages, while interesting [p55] to me as reminiscences, will hardly do for family or studio exhibition. If I should label them, the result would be something like this:

1. Sketch of a footstool and desk where I first saw Miss Schuyler kneeling.

2. Sketch of a carved oak chair, Miss Schuyler sitting in it.

3. ‘Angel choir.’ Heads of Miss Schuyler introduced into the carving.

4. Altar screen. A row of full-length Miss Schuylers holding lilies.

5. Tomb of a bishop, where I tied Miss Schuyler’s shoe.

6. Tomb of another bishop, where I had to tie it again because I did it so badly the first time.

7. Sketch of the shoe, the shoe-lace worn out with much tying.

8. Sketch of the blessed verger who called her ‘Madam’ when we were walking together.

[p56]

9. Sketch of her blush when he did it;

the prettiest thing in the world.

10. Sketch of J. Q. Copley contemplating the ruins of his heart.

‘How are the mighty fallen!’

* * * * *

She

Lincoln,

June 23,

At Miss Smallpage’s, Castle Garden.

This is one of the charmingest towns we have visited, and I am so glad Aunt Celia has a letter to the Canon in residence, because it may keep her contented.

We walked up Steep Hill this morning to see the Jews’ house, but long before we reached it I had seen Mr. Copley sitting on a camp-stool, with his easel in front of him. Wonderful to relate, Aunt Celia recognised him, and was most cordial in her greeting. As for me, I was never so embarrassed in my life. I felt as if he [p57] knew that I had expected to see him in London and Ely and Peterborough, though, of course, he couldn’t know it, even if he looked for, and missed, me in those three dreary and over-estimated places. He had made a most beautiful drawing of the Jews’ House, and completed his conquest of Aunt Celia by presenting it to her. I should like to know when my turn is coming; but, anyway, she asked him to luncheon, and he came, and we had such a cosy, homelike meal together. He is even nicer than he looks, which is saying a good deal more than I should, even to a locked book. Aunt Celia dozed a little after luncheon, and Mr. Copley almost talked in whispers, he was so afraid of disturbing her nap. It is just in these trifling things that one can tell a true man—courtesy to elderly people and consideration for their weaknesses. He has done something in the world; I was sure that he had. He [p58] has a little income of his own, but he is too proud and ambitious to be an idler. He looked so manly when he talked about it, standing up straight and strong in his knickerbockers. I like men in knickerbockers. Aunt Celia doesn’t. She says she doesn’t see how a well-brought-up Copley can go about with his legs in that condition. I would give worlds to know how Aunt Celia ever unbent sufficiently to get engaged. But, as I was saying, Mr. Copley has accomplished something, young as he is. He has built three picturesque suburban churches suitable for weddings, and a State lunatic asylum.

Aunt Celia says we shall have no worthy architecture until every building is made an exquisitely sincere representation of its deepest purpose—a symbol, as it were, of its indwelling meaning. I should think it would be very difficult to design a lunatic asylum on that basis, but I didn’t dare say [p59] so, as the idea seemed to present no incongruities to Mr. Copley. Their conversation is absolutely sublimated when they get to talking of architecture. I have just copied two quotations from Emerson, and am studying them every night for fifteen minutes before I go to sleep. I’m going to quote them some time offhand, just after matins, when we are wandering about the cathedral grounds. The first is this: ‘The Gothic cathedral is a blossoming in stone, subdued by the insatiable demand of harmony in man. The mountain of granite blooms into an eternal flower, with the lightness and delicate finish as well as the aerial proportion and perspective of vegetable beauty.’ Then when he has recovered from the shock of this, here is my second: ‘Nor can any lover of nature enter the old piles of English cathedrals without feeling that the forest overpowered the mind of the builder, and that his chisel, [p60] his saw and plane still reproduced its ferns, its spikes of flowers, its locust, elm, pine, and spruce.’

Memoranda: Lincoln choir is an example of Early English or First Pointed, which can generally be told from something else by bold projecting buttresses and dog-tooth moulding round the abacusses. (The plural is my own, and it does not look right.) Lincoln Castle was the scene of many prolonged sieges, and was once taken by Oliver Cromwell.

* * * * *

He

York,

June 26,

The Black Swan.

Kitty Schuyler is the concentrated essence of feminine witchery. Intuition strong, logic weak, and the two qualities so balanced as to produce an indefinable charm; will-power large, but docility equal, [p61] if a man is clever enough to know how to manage her; knowledge of facts absolutely nil, but she is exquisitely intelligent in spite of it. She has a way of evading, escaping, eluding, and then gives you an intoxicating hint of sudden and complete surrender. She is divinely innocent, but roguishness saves her from insipidity. Her looks? She looks as you would imagine a person might look who possessed these graces; and she is worth looking at, though every time I do it I have a rush of love to the head. When you find a girl who combines all the qualities you have imagined in the ideal, and who has added a dozen or two on her own account, merely to distract you past all hope, why stand up and try to resist her charm? Down on your knees like a man, say I!

* * * * *

I’m getting to adore Aunt Celia. I didn’t care for her at first, but she is so [p62] deliciously blind. Anything more exquisitely unserviceable as a chaperon I can’t imagine. Absorbed in antiquity, she ignores the babble of contemporaneous lovers. That any man could look at Kitty when he could look at a cathedral passes her comprehension. I do not presume too greatly on her absent-mindedness, however, lest she should turn unexpectedly and rend me. I always remember that inscription on the backs of the little mechanical French toys: ‘Quoiqu’elle soit très solidement montée, il faut ne pas brutaliser la machine.’

And so my courtship progresses under Aunt Celia’s very nose. I say ‘progresses’; but it is impossible to speak with any certainty of courting, for the essence of that gentle craft is hope, rooted in labour and trained by love.

I set out to propose to her during service this afternoon by writing my feelings [p64] on the flyleaf of the hymn-book, or something like that; but I knew that Aunt Celia would never forgive such blasphemy, and I thought that Kitty herself might consider it wicked. Besides, if she should chance to accept me, there was nothing I could do in a cathedral to relieve my feelings. No; if she ever accepts me, I wish it to be in a large, vacant spot of the universe, peopled by two only, and those two so indistinguishably blended, as it were, that they would appear as one to the casual observer. So I practised repression, though the wall of my reserve is worn to the thinness of thread-paper, and I tried to keep my mind on the droning minor canon, and not to look at her, ‘for that way madness lies.’

* * * * *

[p65]

She

York,

June 28,

High Petergate Street.

My taste is so bad! I just begin to realize it, and I am feeling my ‘growing pains,’ like Gwendolen in ‘Daniel Deronda.’ I admired the stained glass in the Lincoln Cathedral the other day, especially the Nuremberg window. I thought Mr. Copley looked pained, but he said nothing. When I went to my room, I consulted a book and found that all the glass in that cathedral is very modern and very bad, and the Nuremberg window is the worst of all. Aunt Celia says she hopes that it will be a warning to me to read before I speak; but Mr. Copley says no, that the world would lose more in one way than it would gain in the other. I tried my quotations this morning, and stuck fast in the middle of the first.

Mr. Copley thinks I have been feeing [p66] the vergers too liberally, so I wrote a song about it called ‘The Ballad of the Vergers and the Foolish Virgin,’ which I sang to my guitar. Mr. Copley thinks it is cleverer than anything he ever did with his pencil. Of course, he says that only to be agreeable; but really, whenever he talks to me in that way, I can almost hear myself purring with pleasure.

We go to two services a day in the minster, and sometimes I sit quite alone in the nave drinking in the music as it floats out from behind the choir-screen. The Litany and the Commandments are so beautiful heard in this way, and I never listen to the fresh, young voices chanting ‘Write all these Thy laws in our hearts, we beseech Thee,’ without wanting passionately to be good. I love, too, the joyful burst of music in the Te Deum: ‘Thou didst open the kingdom of heaven to all believers.’ I like that word ‘all’; [p67] it takes in foolish me, as well as wise Aunt Celia.

And yet, with all its pomp and magnificence, the service does not help me quite so much nor stir up the deep places, in me so quickly as dear old Dr. Kyle’s simpler prayers and talks in the village meeting-house where I went as a child. Mr. Copley has seen it often, and made a little picture of it for me, with its white steeple and the elm-tree branches hanging over it. If I ever have a husband I should wish him to have memories like my own. It would be very romantic to marry an Italian marquis or a Hungarian count, but must it not be a comfort to two people to look back on the same past?

* * * * *

We all went to an evening service last night. It was an ‘occasion,’ and a famous organist played the Minster organ.

I wonder why choir-boys are so often [p68] playful and fidgety and uncanonical in behaviour? Does the choirmaster advertise ‘Naughty boys preferred,’ or do musical voices commonly exist in unregenerate bodies? With all the opportunities they must have outside of the cathedral to exchange those objects of beauty and utility usually found in boys’ pockets, there is seldom a service where they do not barter penknives, old coins, or tops, generally during the Old Testament reading. A dozen little black-surpliced ‘probationers’ sit together in a seat just beneath the choir-boys, and one of them spent his time this evening in trying to pull a loose tooth from its socket. The task not only engaged all his own powers, but made him the centre of attraction for the whole probationary row.

Coming home, Aunt Celia walked ahead with Mrs. Benedict, who keeps turning up at the most unexpected moments. She’s going to build a Gothicky memorial chapel [p69] somewhere, and is making studies for it. I don’t like her in the least, but four is certainly a more comfortable number than three. I scarcely ever have a moment alone with Mr. Copley, for, go where I will and do what I please, as Aunt Celia has the most perfect confidence in my indiscretion, she is always en évidence.

Just as we were turning into the quiet little street where we are lodging, I said:

‘Oh dear, I wish that I really knew something about architecture!’

‘If you don’t know anything about it, you are certainly responsible for a good deal of it,’ said Mr. Copley.

‘I? How do you mean?’ I asked quite innocently, because I couldn’t see how he could twist such a remark as that into anything like sentiment.

‘I have never built so many castles in my life as since I’ve known you, Miss Schuyler,’ he said.

[p70]

‘Oh,’ I answered as lightly as I could,

‘air-castles don’t count.’

‘The building of air-castles is an innocent amusement enough, I suppose,’ he said; ‘but I’m committing the folly of living in mine. I—’

Then I was frightened. When, all at once, you find you have something precious that you only dimly suspected was to be yours, you almost wish it hadn’t come so soon. But just at that moment Mrs. Benedict called to us, and came tramping back from the gate, and hooked her supercilious, patronizing arm in Mr. Copley’s, and asked him into the sitting-room to talk over the ‘lady-chapel’ in her new memorial church. Then Aunt Celia told me they would excuse me, as I had had a wearisome day; and there was nothing for me to do but to go to bed, like a snubbed child, and wonder if I should ever know the end of that sentence. And I listened [p71] at the head of the stairs, shivering, but all that I could hear was that Mrs. Benedict asked Mr. Copley to be her own architect. Her architect, indeed! That woman ought not to be at large—so rich and good-looking and unconscientious!

* * * * *

He

York, July 5.

I had just established myself comfortably near to Miss Van Tyck’s hotel, and found a landlady after my own heart in Mrs. Pickles, No. 6, Micklegate, when Miss Van Tyck, aided and abetted, I fear, by the romantic Miss Schuyler, elected to change her quarters, and I, of course, had to change too. Mine is at present a laborious (but not unpleasant) life. The causes of Miss Schuyler’s removal, as I have been given to understand by the lady herself, were some particularly pleasing window-boxes in a lodging in High Petergate [p72] Street; boxes overflowing with pink geraniums and white field-daisies. No one (she explains) could have looked at this house without desiring to live in it; and when she discovered, during a somewhat exhaustive study of the premises, that the maid’s name was Susan Strangeways, and that she was promised in marriage to a brewer’s apprentice called Sowerbutt, she went back to her conventional hotel and persuaded her aunt to remove without delay. If Miss Schuyler were offered a room at the Punchbowl Inn in the Gillygate and a suite at the Grand Royal Hotel in Broad Street, she would choose the former unhesitatingly; just as she refused refreshment at the best caterer’s this afternoon and dragged Mrs. Benedict and me into ‘The Little Snug,’ where an alluring sign over the door announced ‘A Homely Cup of Tea for Twopence.’ But she would outgrow all that; or, if she didn’t, I have [p73] common-sense enough for two; or if I hadn’t, I shouldn’t care a hang.

Is it not a curious dispensation of Providence that, just when Aunt Celia is confined to her room with a cold, Mrs. Benedict should join our party and spend her days in our company? She drove to the Merchants’ Hall and the Cavalry Barracks with us, she walked on the city walls with us, she even dared the ‘homely’ tea at ‘The Little Snug’; and at that moment I determined I wouldn’t build her memorial church for her, even at a most princely profit.

On crossing Lendal Bridge we saw the river Ouse running placidly through the town, and a lot of little green boats moored at a landing-stage.

‘How delightful it would be to row for an hour!’ exclaimed Miss Schuyler.

‘Oh, do you think so, in those tippy boats on a strange river?’ remonstrated Mrs. Benedict.

[p74]

The moment I suspected she was afraid

of the water, I lured her to the landing-stage

and engaged a boat.

‘It’s a pity that that large flat one has a leak, otherwise it would have held three nicely; but I dare say we can be comfortable in one of the little ones,’ I said doubtfully.

‘Shan’t we be too heavy for it?’ Mrs. Benedict inquired timidly.

‘Oh, I don’t think so. We’ll get in and try it. If we find it sinks under our weight we won’t risk it,’ I replied, spurred on by such twinkles in Miss Schuyler’s eyes as blinded me to everything else.

‘I really don’t think your aunt would like you to venture, Miss Schuyler,’ said the marplot.

‘Oh, as to that, she knows I am accustomed to boating,’ replied Miss Schuyler.

‘And Miss Schuyler is such an excellent swimmer,’ I added.

Whereupon the marplot and killjoy [p75] remarked that if it were a question of swimming she should prefer to remain at home, as she had large responsibilities devolving upon her, and her life was in a sense not her own to fling away as she might like.

I assured her solemnly that she was quite, quite right, and pushed off before she could change her mind.

After a long interval of silence, Miss Schuyler observed in the voice, accompanied by the smile and the glance of the eye, that ‘did’ for me the moment I was first exposed to them:

‘You oughtn’t to have said that about my swimming, because I can’t a bit, you know.’

‘I was justified,’ I answered gloomily. ‘I have borne too much to-day, and if she had come with us and had fallen overboard, I might have been tempted to hold her down with the oar.’

Whereupon Miss Schuyler gave way to [p76] such whole-hearted mirth that she nearly upset the boat. I almost wish she had! I want to swim, sink, die, or do any other mortal thing for her.

We had a heavenly hour. It was only an hour, but it was the first time I have had any real chance to direct hot shot at the walls of the maiden castle. I regret to state that they stood remarkably firm. Of course, I don’t wish to batter them down; I want them to melt under the warmth of my attack.

She

York, July 5.

We had a lovely sail on the river Ouse this afternoon. Mrs. Benedict was timid about boating, and did not come with us. As a usual thing, I hate a cowardly woman, but her lack of courage is the nicest trait in her whole character; I might almost say the only nice trait.

[p77]

Mr. Copley tried in every way, short of

asking me a direct question, to find out

whether I had received the marked copy

of ‘Persuasion’ in Bath, but I evaded the

point.

Just as we were at the door of my lodging, and he was saying good-bye, I couldn’t resist the temptation of asking:

‘Why, before you knew us at all, did you put “Miss Van Tyck: Reserved,” on the window of the railway carriage at Bath?’

He was embarrassed for a moment, and then he said:

‘Well, she is, you know, if you come to that; and, besides, I didn’t dare tell the guard the placard I really wanted to put on.’

‘I shouldn’t think a lack of daring your most obvious fault,’ I said cuttingly.

‘Perhaps not; but there are limits to most things, and I hadn’t the pluck to paste on a pink paper with “Miss Schuyler: Engaged,” on it.’

[p78]

He disappeared suddenly just then, as if

he wasn’t equal to facing my displeasure,

and I am glad he did, for I was too

embarrassed for words.

Memoranda: In the height of roofs, nave, and choir, York is first of English cathedrals.

She

Durham,

July something or other,

At Farmer Hendry’s.

We left York this morning, and arrived in Durham about eleven o’clock. It seems there is some sort of an election going on in the town, and there was not a single fly at the station. Mr. Copley looked about in every direction, but neither horse nor vehicle was to be had for love or money. At last we started to walk to the village, Mr. Copley so laden with our hand-luggage that he resembled a pack mule.

We called first at the Three Tuns, where [p79] they still keep up the old custom of giving a wee glass of cherry-brandy to each guest on his arrival; but, alas! they were crowded, and we were turned from the hospitable door. We then made a tour of the inns, but not a single room was to be had, not for that night, nor for two days ahead, on account of that same election.

‘Hadn’t we better go on to Edinburgh, Aunt Celia?’ I asked, as we were resting in the door of the Jolly Sailor.

‘Edinburgh? Never!’ she replied. ‘Do you suppose that I would voluntarily spend a Sunday in those bare Presbyterian churches until the memory of these past ideal weeks has faded a little from my memory? What! leave out Durham and spoil the set?’ (In her agitation and disappointment she spoke of the cathedrals as if they were souvenir spoons.) ‘I intended to stay here for a week or more, [p80] and write up a record of our entire trip from Winchester while the impressions were fresh in my mind.’

‘And I had intended doing the same thing,’ said Mr. Copley. ‘That is, I hoped to finish off my previous sketches, which are in a frightful state of incompletion, and spend a good deal of time on the interior of this cathedral, which is unusually beautiful.’

At this juncture Aunt Celia disappeared for a moment to ask the barmaid if, in her opinion, the constant consumption of malt liquors prevents a more dangerous indulgence in brandy and whisky. She is gathering statistics, but as the barmaids can never collect their thoughts while they are drawing ale, Aunt Celia proceeds slowly.

‘For my part,’ said I, with mock humility, ‘I am a docile person, who never has any intentions of her own, but who [p81] yields herself sweetly to the intentions of other people in her immediate vicinity.’

‘Are you?’ asked Mr. Copley, taking out his pencil.

‘Yes, I said so. What are you doing?’

‘Merely taking note of your statement, that’s all. Now, Miss Van Tyck’ (of course Aunt Celia appeared at this delightful moment), ‘I have a plan to propose. I was here last summer with a couple of Harvard men, and we lodged at a farmhouse about a mile distant from the cathedral. If you will step into the coffee-room for an hour, I’ll walk up to Farmer Hendry’s and see if they will take us in. I think we might be fairly comfortable.’

‘Can Aunt Celia have Apollinaris and black coffee after her morning bath?’ I asked.

‘I hope, Katharine,’ said Aunt Celia majestically—‘I hope that I can accommodate myself to circumstances. If [p82] Mr. Copley can secure apartments for us, I shall be more than grateful.’

So here we are, all lodging together in an ideal English farmhouse. There is a thatched roof on one of the old buildings, and the dairy-house is covered with ivy, and Farmer Hendry’s wife makes a real English curtsey, and there are herds of beautiful sleek Durham cattle, and the butter and cream and eggs and mutton are delicious, and I never, never want to go home any more. I want to live here for ever and wave the American flag on Washington’s birthday.

I am so happy that I feel as if something were going to spoil it all. Twenty years old to-day! I wish mamma were alive to wish me many happy returns.

The cathedral is very beautiful in itself, and its situation is beyond all words of mine to describe. I greatly admired the pulpit, which is supported by five pillars [p83] sunk into the backs of squashed lions; but Mr. Copley, when I asked him the period, said, ‘Pure Brummagem!’

There is a nice old cell for refractory monks, that we agreed will be a lovely place for Mrs. Benedict if we can lose her in it. She arrives as soon as they can find room for her at the Three Tuns.

Memoranda:—Casual remark for breakfast-table or perhaps for luncheon—it is a trifle heavy for breakfast: ‘Since the sixteenth century, and despite the work of Inigo Jones and the great Wren (not Jenny Wren: Christopher), architecture has had, in England especially, no legitimate development.’ This is the only cathedral with a Bishop’s Throne or a Sanctuary Knocker.

* * * * *

[p84]

He

Durham, July 19.

O child of fortune, thy name is J. Q. Copley! How did it happen to be election time? Why did the inns chance to be full? How did Aunt Celia relax sufficiently to allow me to find her a lodging? Why did she fall in love with the lodging when found? I do not know. I only know Fate smiles; that Kitty and I eat our morning bacon and eggs together; that I carve Kitty’s cold beef and pour Kitty’s sparkling ale at luncheon; that I go to matins with Kitty, and dine with Kitty, and walk in the gloaming with Kitty—and Aunt Celia. And after a day of heaven like this, like Lorna Doone’s lover—ay, and like every other lover, I suppose—I go to sleep, and the roof above me swarms with angels, having Kitty under it.

[p85]

She was so beautiful on Sunday. She

has been wearing her favourite browns and

primroses through the week, but on Sunday

she blossomed into blue and white, topped

by a wonderful hat, whose brim was laden

with hyacinths. She sat on the end of a

seat in the nave, and there was a capped

and gowned crowd of university students

in the transept. I watched them and they

watched her. She has the fullest, whitest

eyelids, and the loveliest lashes. When

she looks down I wish she might never

look up, and when she looks up I am

never ready for her to look down. If it

had been a secular occasion, and she had

dropped her handkerchief, seven-eighths

of the students would have started to pick

it up—but I should have got there first!

Well, all this is but a useless prelude,

for there are facts to be considered—delightful,

warm, breathing facts!

We were coming home from evensong, [p86] Kitty and I. (I am anticipating, for she was still ‘Miss Schuyler’ then, but never mind.) We were walking through the fields, while Mrs. Benedict and Aunt Celia were driving. As we came across a corner of the bit of meadow land that joins the stable and the garden, we heard a muffled roar, and as we looked around we saw a creature with tossing horns and waving tail making for us, head down, eyes flashing. Kitty gave a shriek. We chanced to be near a pair of low bars. I hadn’t been a college athlete for nothing. I swung Kitty over the bars, and jumped after her. But she, not knowing in her fright where she was nor what she was doing, supposing also that the mad creature, like the villain in the play, would ‘still pursue her,’ flung herself bodily into my arms, crying, ‘Jack! Jack! save me!’

It was the first time she had called me ‘Jack,’ and I needed no second invitation. [p87] I proceeded to save her, in the usual way, by holding her to my heart and kissing her lovely hair reassuringly as I murmured:

‘You are safe, my darling; not a hair of your precious head shall be hurt. Don’t be frightened.’

She shivered like a leaf.

‘I am frightened,’ she said; ‘I can’t help being frightened. He will chase us, I know. Where is he? What is he doing now?’

Looking up to determine if I need abbreviate this blissful moment, I saw the enraged animal disappearing in the side-door of the barn; and it was a nice, comfortable Durham cow, that somewhat rare but possible thing—a sportive cow.

‘Is he gone?’ breathed Kitty from my waistcoat.

‘Yes, he is gone—she is gone, darling. But don’t move; it may come again.’

[p88]

My first too hasty assurance had calmed

Kitty’s fears, and she raised her charming

flushed face from its retreat and prepared

to withdraw. I did not facilitate the preparations,

and a moment of awkward

silence ensued.

‘Might I inquire,’ I asked, ‘if the dear little person at present reposing in my arms will stay there (with intervals for rest and refreshment) for the rest of her natural life?’

She withdrew entirely now, all but her hand, and her eyes sought the ground.

‘I suppose I shall have to—that is, if you think—at least, I suppose you do think—at any rate, you look as if you were thinking—that this has been giving you encouragement.’

‘I do indeed—decisive, undoubted, bare-faced encouragement.’

‘I don’t think I ought to be judged as [p89] if I were in my sober senses,’ she replied. ‘I was frightened within an inch of my life. I told you this morning that I was dreadfully afraid of bulls, especially mad ones, and I told you that my nurse frightened me, when I was a child, with awful stories about them, and that I never outgrew my childish terror. I looked everywhere about. The barn was too far, the fence too high; I saw him coming, and there was nothing but you and the open country. Of course, I took you. It was very natural, I’m sure; any girl would have done it.’

‘To be sure,’ I replied soothingly, ‘any girl would have run after me, as you say.’

‘I didn’t say any girl would have run after you—you needn’t flatter yourself; and besides, I think I was really trying to protect you as well as to gain protection, else why should I have cast myself on you [p90] like a catamount, or a catacomb, or whatever the thing is?’

‘Yes, darling, I thank you for saving my life, and I am willing to devote the remainder of it to your service as a pledge of my gratitude; but if you should take up life-saving as a profession, dear, don’t throw yourself on a fellow with—’

‘Jack! Jack!’ she cried, putting her hand over my lips, and getting it well kissed in consequence. ‘If you will only forget that, and never, never taunt me with it afterwards, I’ll—I’ll—well, I’ll do anything in reason—yes, even marry you!’

* * * * *

He

Canterbury,

July 31,

The Royal Fountain.

I was never sure enough of Kitty, at first, to dare risk telling her about that [p91] little mistake of hers. She is such an elusive person that I spend all my time in wooing her, and can never lay the flattering unction to my soul that she is really won.

But after Aunt Celia had looked up my family record and given a provisional consent, and Papa Schuyler had cabled a reluctant blessing, I did not feel capable of any further self-restraint.

It was twilight here in Canterbury, and we were sitting on the vine-shaded veranda of Aunt Celia’s lodging. Kitty’s head was on my shoulder. There is something very queer about that; when Kitty’s head is on my shoulder, I am not capable of any consecutive train of thought. When she puts it there I see stars, then myriads of stars, then, oh! I can’t begin to enumerate the steps by which ecstasy mounts to delirium; but, at all events, any operation which demands exclusive use of the intellect [p92] is beyond me at these times. Still, I gathered my stray wits together, and said:

‘Kitty!’

‘Yes, Jack?’

‘Now that nothing but death or marriage can separate us, I have something to confess to you.’

‘Yes,’ she said serenely, ‘I know what you are going to say. He was a cow.’

I lifted her head from my shoulder sternly, and gazed into her childlike, candid eyes.

‘You mountain of deceit! How long have you known about it?’

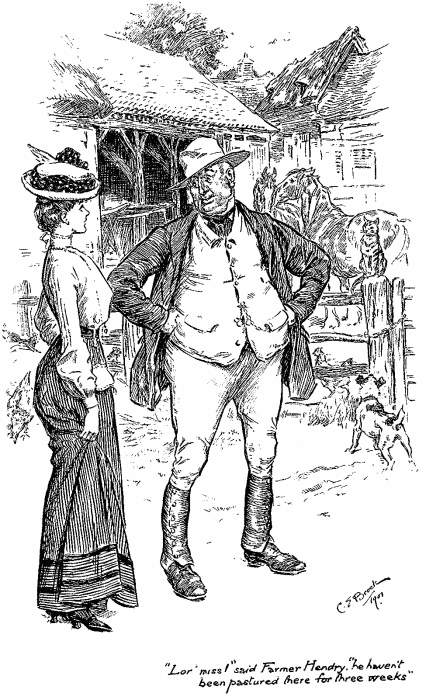

‘Ever since the first. Oh, Jack, stop looking at me in that way! Not the very first, not when I—not when you—not when we—no, not then, but the next morning, I said to Farmer Hendry, “I wish you would keep your savage bull [p94] chained up while we are here; Aunt Celia is awfully afraid of them, especially those that go mad, like yours!” “Lor’, miss!” said Farmer Hendry, “he haven’t been pastured here for three weeks. I keep him six mile away. There ben’t nothing but gentle cows in the home medder.” But I didn’t think that you knew, you secretive person! I dare say you planned the whole thing in advance, in order to take advantage of my fright!’

‘Never! I am incapable of such an unnecessary subterfuge! Besides, Kitty, I could not have made an accomplice of a cow, you know.’

‘Then,’ she said, with great dignity, ‘if you had been a gentleman and a man of honour, you would have cried, “Unhand me, girl! You are clinging to me under a misunderstanding!”’

[p95]

She

Chester,

August 8,

The Grosvenor.

Jack and I are going over this same ground next summer on our wedding journey. We shall sail for home next week, and we haven’t half done justice to the cathedrals. After the first two, we saw nothing but each other on a general background of architecture. I hope my mind is improved, but oh, I am so hazy about all the facts I have read since I knew Jack! Winchester and Salisbury stand out superbly in my memory. They acquired their ground before it was occupied with other matters. I shall never forget, for instance, that Winchester has the longest spire and Salisbury the highest nave of all the English cathedrals. And I shall never forget so long as I live that Jane Austen and Isaac Newt— Oh [p96] dear! was it Isaac Newton or Izaak Walton that was buried in Winchester and Salisbury? To think that that interesting fact should have slipped from my mind, after all the trouble I took with it! But I know that it was Isaac somebody, and that he was buried in—well, he was buried in one of those two places. I am not certain which, but I can ask Jack; he is sure to know.

THE END

BILLING AND SONS, LTD., PRINTERS, GUILDFORD