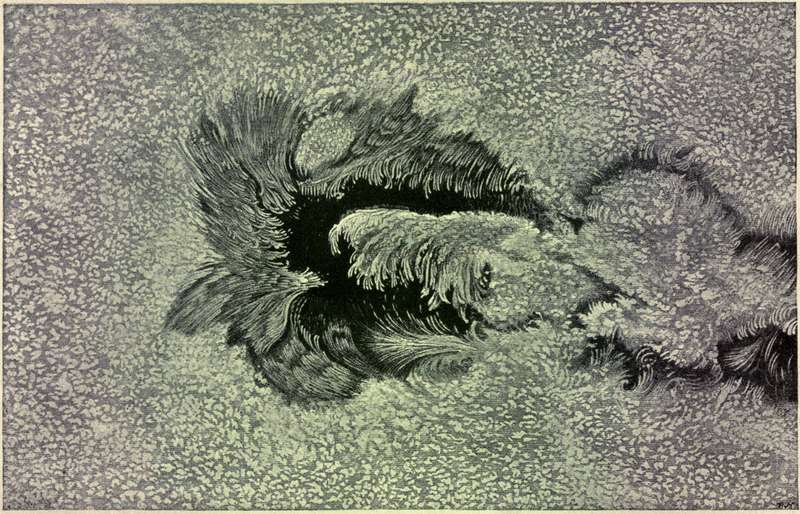

A TYPICAL SUN-SPOT

A TYPICAL SUN-SPOT

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Astronomy of Milton's 'Paradise Lost', by Thomas Orchard This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Astronomy of Milton's 'Paradise Lost' Author: Thomas Orchard Release Date: March 29, 2009 [EBook #28434] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ASTRONOMY *** Produced by David Edwards, Nigel Blower and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Minor punctuation and hyphenation inconsistencies have been corrected.

The following minor typographical errors have been corrected:

p75: “establish” changed to “established”

p99: “Firmanent” changed to “Firmament”

p111: “they thoughts” changed to “thy thoughts”

p120: “suen” changed to “seuen”

p134: “consequenc” changed to “consequence”

p146: “geographieal” changed to “geographical”

p167: “Lyrae” changed to “Lyræ” for consistency

p286: Removed redundant word “degrees” following the degree symbol

The spelling “Bernices” for “Berenices” has been retained throughout.

Ditto marks in the table on page 66 have been replaced with words.

|

These are thy glorious works, Parent of good, Almighty! thine this universal frame, Thus wondrous fair: Thyself how wondrous then! Unspeakable. |

| A Typical Sun-spot | Frontispiece |

| Venus on the Sun’s Disc | To face page 66 |

| Cluster in Hercules | ”218 |

| Great Nebula in Orion | ”230 |

| A Portion of the Moon’s Surface | ”268 |

Many able and cultured writers have delighted to expatiate on the beauties of Milton’s ‘Paradise Lost,’ and to linger with admiration over the lofty utterances expressed in his poem. Though conscious of his inability to do justice to the sublimest of poets and the noblest of sciences, the author has ventured to contribute to Miltonic literature a work which he hopes will prove to be of an interesting and instructive character. Perhaps the choicest passages in the poem are associated with astronomical allusion, and it is chiefly to the exposition and illustration of these that this volume is devoted.

The writer is indebted to many authors for information and reference, and especially to Miss Agnes M. Clerke, Professors Masson and Young, Mr. James Nasmyth, Mr. G. F. Chambers, and Sir Robert Ball. Also to the works of the late Mr.[Pg vi] R. A. Proctor, Sirs W. and J. Herschel, Admiral Smyth, Professor Grant, Mr. J. R. Hind, Sir David Brewster, Rev. A. B. Whatton, and Prebendary Webb.

Most of the illustrations have been supplied by the Publishers: Messrs. Macmillan and W. Hunt & Co. have kindly permitted the reproduction of some of their drawings.

Manchester, March 1896.

Astronomy is the oldest and most sublime of all the sciences. To a contemplative observer of the heavens, the number and brilliancy of the stars, the lustre of the planets, the silvery aspect of the Moon, with her ever-changing phases, together with the order, the harmony, and unison pervading them all, create in his mind thoughts of wonder and admiration. Occupying the abyss of space indistinguishable from infinity, the starry heavens in grandeur and magnificence surpass the loftiest conceptions of the human mind; for, at a distance beyond the range of ordinary vision, the telescope reveals clusters, systems, galaxies, universes of stars—suns—the innumerable host of heaven, each shining with a splendour comparable with that of our Sun, and, in all likelihood, fulfilling in a similar manner the same beneficent purposes.

The time when man began to study the stars is[Pg 2] lost in the antiquity of prehistoric ages. The ancient inhabitants of the Earth regarded the heavenly bodies with veneration and awe, erected temples in their honour, and worshipped them as deities. Historical records of astronomy carry us back several thousand years. During the greater part of this time, and until a comparatively recent period, astronomy was associated with astrology—a science which originated from a desire on the part of mankind to penetrate the future, and which was based upon the supposed influence of the heavenly bodies upon human and terrestrial affairs. It was natural to imagine that the overruling power which governed and directed the course of sublunary events resided in the heavens, and that its decrees might be understood by watching the movements of the heavenly bodies under its control. It was, therefore, believed that by observing the configuration of the planets and the positions of the constellations at the instant of the birth of an individual, his horoscope, or destiny, could be foretold; and that by making observations of a somewhat similar nature the occurrence of events of public importance could be predicted. When, however, the laws which govern the motions of the heavenly bodies became better known, and especially after the discovery of the great law of gravitation, astrology ceased to be a belief, though for long after it retained its power over the imagination, and was often alluded to in the writings of poets and other authors.

[Pg 3] In the early dawn of astronomical science, the theories upheld with regard to the structure of the heavens were of a simple and primitive nature, and might even be described as grotesque. This need occasion no surprise when we consider the difficulties with which ancient astronomers had to contend in their endeavours to reduce to order and harmony the complicated motions of the orbs which they beheld circling around them.

The grouping of the stars into constellations having fanciful names, derived from fable or ancient mythology, occurred at a very early period, and though devoid of any methodical arrangement, is yet sufficiently well-defined to serve the purposes of modern astronomers. Several of the ancient nations of the earth, including the Chaldeans, Egyptians, Hindus, and Chinese, claim to have been the earliest astronomers. Chinese records of astronomy reveal an antiquity of near 3,000 years B.C., but they contain no evidence that their authors possessed any scientific knowledge, and they merely record the occurrence of solar eclipses and the appearances of comets.

It is not known when astronomy was first studied by the Egyptians; but what astronomical information they have handed down is not of a very intelligible kind, nor have they left behind any data that can be relied upon. The Great Pyramid, judging from the exactness with which it faces the cardinal points, must have been designed by persons who possessed a good knowledge of astronomy, and[Pg 4] it was probably made use of for observational purposes.

It is now generally admitted that correct astronomical observations were first made on the plains of Chaldea, records of eclipses having been discovered in Chaldean cities which date back 2,234 years B.C. The Chaldeans were true astronomers: they made correct observations of the risings and settings of the heavenly bodies; and the exact orientation of their temples and public buildings indicates the precision with which they observed the positions of celestial objects. They invented the zodiac and gnomon, made use of several kinds of dials, notified eclipses, and divided the day into twenty-four hours.

To the Greeks belongs the credit of having first studied astronomy in a regular and systematic manner. Thales (640 B.C.) was one of the earliest of Greek astronomers, and may be regarded as the founder of the science among that people. He was born at Miletus, and afterwards repaired to Egypt for the purpose of study. On his return to Greece he founded the Ionian school, and taught the sphericity of the Earth, the obliquity of the ecliptic, and the true causes of eclipses of the Sun and Moon. He also directed the attention of mariners to the superiority of the Lesser Bear, as a guide for the navigation of vessels, as compared with the Great Bear, by which constellation they usually steered. Thales believed the Earth to be the centre of the universe, and that the stars were composed of fire;[Pg 5] he also predicted the occurrence of a great solar eclipse.

Thales had for his successors Anaximander, Anaximenes, and Anaxagoras, who taught the doctrines of the Ionian school.

The next great astronomer that we read of is Pythagoras, who was born at Samos 590 B.C. He studied under Thales, and afterwards visited Egypt and India, in order that he might make himself familiar with the scientific theories adopted by those nations. On his return to Europe he founded his school in Italy, and taught in a more extended form the doctrines of the Ionian school. In his speculations with regard to the structure of the universe he propounded the theory (though the reasons by which he sustained it were fanciful) that the Sun is the centre of the planetary system, and that the Earth revolves round him. This theory—the accuracy of which has since been confirmed—received but little attention from his successors, and it sank into oblivion until the time of Copernicus, by whom it was revived. Pythagoras discovered that the Morning and Evening Stars are one and the same planet.

Among the famous astronomers who lived about this period we find recorded the names of Meton, who introduced the Metonic cycle into Greece and erected the first sundial at Athens; Eudoxus, who persuaded the Greeks to adopt the year of 365¼ days; and Nicetas, who taught that the Earth completed a daily revolution on her axis.

[Pg 6] The Alexandrian school, which flourished for three centuries prior to the Christian era, produced men of eminence whose discoveries and investigations, when arranged and classified, enabled astronomy to be regarded as a true theoretical science. The positions of the fixed stars and the paths of the planets were determined with greater accuracy, and irregularities of the motions of the Sun and Moon were investigated with greater precision. Attempts were made to ascertain the distance of the Sun from the Earth, and also the dimensions of the terrestrial sphere. The obliquity of the ecliptic was accurately determined, and an arc of the meridian was measured between Syene and Alexandria. The names of Aristarchus, Eratosthenes, Aristyllus, Timocharis, and Autolycus, are familiarly known in association with the advancement of the astronomy of this period.

We now reach the name of Hipparchus of Bithynia (140 B.C.), the most illustrious astronomer of antiquity, who did much to raise astronomy to the position of a true science, and who has also left behind him ample evidence of his genius ‘as a mathematician, an observer, and a theorist.’ We are indebted to him for the earliest star catalogue, in which he included 1,081 stars. He discovered the Precession of the Equinoxes, and determined the motions of the Sun and Moon, and also the length of the year, with greater precision than any of his predecessors. He invented the sciences of plane and spherical trigonometry, and was the first to use right ascensions and declinations.

[Pg 7] The next astronomer of eminence after Hipparchus was Ptolemy (130 A.D.), who resided at Alexandria. He was skilled as a mathematician and geographer, and also excelled as a musician. His chief discovery was an irregularity of the lunar motion, called the ‘evection.’ He was also the first to observe the effect of the refraction of light in causing the apparent displacement of a heavenly body from its true position. Ptolemy devoted much of his time to extending and improving the theories of Hipparchus, and compiled a great treatise, called the ‘Almagest,’ which contains nearly all the knowledge we possess of ancient astronomy. Ptolemy’s name is, however, most widely known in association with what is called the Ptolemaic theory. This system, which originated long before his time, but of which he was one of the ablest expounders, was an attempt to establish on a scientific basis the conclusions and results arrived at by early astronomers who studied and observed the motions of the heavenly bodies. Ptolemy regarded the Earth as the immovable centre of the universe, round which the Sun, Moon, planets, and the entire heavens completed a daily revolution in twenty-four hours. After the death of Ptolemy no worthy successor was found to occupy his place, the study of astronomy began to decline among the Greeks, and after a time it ceased to be cultivated by that people.

The Arabs next took up the study of astronomy, which they prosecuted most assiduously for a period of four centuries. Their labours were, however,[Pg 8] confined chiefly to observational work, in which they excelled; unlike their predecessors, they paid but little attention to speculative theories—indeed, they regarded with such veneration the opinions held by the Greeks, that they did not feel disposed to question the accuracy of their doctrines. The most eminent astronomer among the Arabs was Albategnius (680 A.D.). He corrected the Greek observations, and made several discoveries which testified to his abilities as an observer. Ibn Yunis and Abul Wefu were Arab astronomers who earned a high reputation on account of the number and accuracy of their observations. In Persia, a descendant of the famous Genghis Khan erected an observatory, where astronomical observations were systematically made. Omar, a Persian astronomer, suggested a reformation of the calendar which, if it had been adopted, would have insured greater accuracy than can be attained by the Gregorian style now in use. In 1433, Ulugh Beg, who resided at Samarcand, made many observations, and constructed a star catalogue of greater exactness than was known to exist prior to his time. The Arabs may be regarded as having been the custodians of astronomy until the time of its revival in another quarter of the Globe.

After the lapse of many centuries, astronomy was introduced into Western Europe in 1220, and from that date to the present time its career has been one of triumphant progress. In 1230, a translation of Ptolemy’s ‘Almagest’ from Arabic into[Pg 9] Latin was accomplished by order of the German Emperor, Frederick II.; and in 1252 Alphonso X., King of Castile, himself a zealous patron of astronomy, caused a new set of astronomical tables to be constructed at his own expense, which, in honour of his Majesty, were called the ‘Alphonsine Tables.’ Purbach and Regiomontanus, two German astronomers of distinguished reputation, and Waltherus, a man of considerable renown, made many important observations in the fifteenth century.

The most eminent astronomer who lived during the latter part of this century was Copernicus. Nicolas Copernicus was born February 19, 1473, at Thorn, a small town situated on the Vistula, which formed the boundary between the kingdoms of Prussia and Poland. His father was a Polish subject, and his mother of German extraction. Having lost his parents early in life, he was educated under the supervision of his uncle Lucas, Bishop of Ermland. Copernicus attended a school at Thorn, and afterwards entered the University of Cracow, in 1491, where he devoted four years to the study of mathematics and science. On leaving Cracow he attached himself to the University of Bologna as a student of canon law, and attended a course of lectures on astronomy given by Novarra. In the ensuing year he was appointed canon of Frauenburg, the cathedral city of the Diocese of Ermland, situated on the shores of the Frisches Haff. In the year 1500 he was at Rome, where he lectured on mathematics and astronomy. He next[Pg 10] spent a few years at the University of Padua, where, besides applying himself to mathematics and astronomy, he studied medicine and obtained a degree. In 1505 Copernicus returned to his native country, and was appointed medical attendant to his uncle, the Bishop of Ermland, with whom he resided in the stately castle of Heilsberg, situated at a distance of forty-six miles from Frauenburg. Copernicus lived with his uncle from 1507 till 1512, and during that time prosecuted his astronomical studies, and undertook, besides, many arduous duties associated with the administration of the diocese; these he faithfully discharged until the death of the Bishop, which occurred in 1512. After the death of his uncle he took up his residence at Frauenburg, where he occupied his time in meditating on his new astronomy and undertaking various duties of a public character, which he fulfilled with credit and distinction. In 1523 he was appointed Administrator-General of the diocese. Though a canon of Frauenburg, Copernicus never became a priest.

After many years of profound meditation and thought, Copernicus, in a treatise entitled ‘De Revolutionibus Orbium Celestium,’ propounded a new theory, or, more correctly speaking, revived the ancient Pythagorean system of the universe. This great work, which he dedicated to Pope Paul III., was completed in 1530; but he could not be prevailed upon to have it published until 1543, the year in which he died. In 1542 Copernicus had an apoplectic[Pg 11] seizure, followed by paralysis and a gradual decay of his mental and vital powers. His book was printed at Nuremberg, and the first copy arrived at Frauenburg on May 24, 1543, in time to be touched by the hands of the dying man, who in a few hours after expired. The house in which Copernicus lived at Allenstein is still in existence, and in the walls of his chamber are visible the perforations which he made for the purpose of observing the stars cross the meridian.

Copernicus was the means of creating an entire revolution in the science of astronomy, by transferring the centre of our system from the Earth to the Sun. He accounted for the alternation of day and night by the rotation of the Earth on her axis, and for the vicissitudes of the seasons by her revolution round the Sun. He devoted the greater part of his life to meditating on this theory, and adduced several weighty reasons in its support. Copernicus could not help perceiving the complications and entanglements by which the Ptolemaic system of the universe was surrounded, and which compared unfavourably with the simple and orderly manner in which other natural phenomena presented themselves to his observation. By perceiving that Mars when in opposition was not much inferior in lustre to Jupiter, and when in conjunction resembled a star of the second magnitude, he arrived at the conclusion that the Earth could not be the centre of the planet’s motion. Having discovered in some ancient manuscripts a theory, ascribed to the Egyptians, that Mercury[Pg 12] and Venus revolved round the Sun, whilst they accompanied the orb in his revolution round the Earth, Copernicus was able to perceive that this afforded him a means of explaining the alternate appearance of those planets on each side of the Sun. The varied aspects of the superior planets, when observed in different parts of their orbits, also led him to conclude that the Earth was not the central body round which they accomplished their revolutions. As a combined result of his observation and reasoning Copernicus propounded the theory that the Sun is the centre of our system, and that all the planets, including the Earth, revolve in orbits around him. This, which is called the Copernican system, is now regarded as, and has been proved to be, the true theory of the solar system.

Tycho Brahé was a celebrated Danish astronomer, who earned a deservedly high reputation on account of the number and accuracy of his astronomical observations and calculations. The various astronomical tables that were in use in his time contained many inaccuracies, and it became necessary that they should be reconstructed upon a more correct basis. Tycho possessed the practical skill required for this kind of work.

He was born December 14, 1546, at Knudstorp, near Helsingborg. His father, Otto Brahé, traced his descent from a Swedish family of noble birth. At the age of thirteen Tycho was sent to the University of Copenhagen, where it was intended he should prepare himself for the study of the law.

[Pg 13] The prediction of a great solar eclipse, which was to happen on August 21, 1560, caused much public excitement in Denmark, for in those days such phenomena were regarded as portending the occurrence of events of national importance. Tycho looked forward with great eagerness to the time of the eclipse. He watched its progress with intense interest, and when he perceived all the details of the phenomenon occur exactly as they were predicted, he resolved to pursue the study of a science by which, as was then believed, the occurrence of future events could be foretold. From Copenhagen Tycho Brahé was sent to Leipsic to study jurisprudence, but astronomy absorbed all his thoughts. He spent his pocket-money in purchasing astronomical books, and, when his tutor had retired to sleep, he occupied his time night after night in watching the stars and making himself familiar with their courses. He followed the planets in their direct and retrograde movements, and with the aid of a small globe and pair of compasses was able by means of his own calculations to detect serious discrepancies in the Alphonsine and Prutenic tables. In order to make himself more proficient in calculating astronomical tables he studied arithmetic and geometry, and learned mathematics without the aid of a master. Having remained at Leipsic for three years, during which time he paid far more attention to the study of astronomy than to that of law, he returned to his native country in consequence of the death of an uncle, who bequeathed him a considerable[Pg 14] estate. In Denmark he continued to prosecute his astronomical studies, and incurred the displeasure of his friends, who blamed him for neglecting his intended profession and wasting his time on astronomy, which they regarded as useless and unprofitable.

Not caring to remain among his relatives, Tycho Brahé returned to Germany, and arrived at Wittenberg in 1566. Whilst residing here he had an altercation with a Danish gentleman over some question in mathematics. The quarrel led to a duel with swords, which terminated rather unfortunately for Tycho, who had a portion of his nose cut off. This loss he repaired by ingeniously contriving one of gold, silver, and wax, which was said to bear a good resemblance to the original. From Wittenberg Tycho proceeded to Augsburg, where he resided for two years. Here he made the acquaintance of several men distinguished for their learning and their love of astronomy. During his stay at Augsburg he constructed a quadrant of fourteen cubits radius, on which were indicated the single minutes of a degree; he made many valuable observations with this instrument, which he used in combination with a large sextant.

In 1571 Tycho returned to Denmark, where his fame as an astronomer had preceded him, and was the means of procuring for him a hearty welcome from his relatives and friends. In 1572, when returning one night from his laboratory—for Tycho studied alchemy as well as astronomy—he beheld[Pg 15] what appeared to be a new and brilliant star in the constellation Cassiopeia, which was situated overhead. He directed the attention of his companions to this wonderful object, and all declared that they had never observed such a star before. On the following night he measured its distance from the nearest stars in the constellation, and arrived at the conclusion that it was a fixed star, and beyond our system.

This remarkable object remained visible for sixteen months, and when at its brightest rivalled Sirius. At first it was of a brilliant white colour, but as it diminished in size it became yellow; it next changed to a red colour, resembling Aldebaran; afterwards it appeared like Saturn, and as it grew smaller it decreased in brightness, until it finally became invisible. In 1573 Tycho Brahé married a peasant-girl from the village of Knudstorp. This imprudent act roused the resentment of his relatives, who, being of noble birth, were indignant that he should have contracted such an alliance. The bitterness and mutual ill-feeling created by this affair became so intense that the King of Denmark deemed it advisable to endeavour to bring about a reconciliation.

After this Tycho returned to Germany, and visited several cities before deciding where he should take up his permanent residence.

His fame as an astronomer was now so great that he was received with distinction wherever he went, and on the occasion of a visit to Hesse-Cassel[Pg 16] he spent a few pleasant days with William, Landgrave of Hesse, who was himself skilled in astronomy.

Frederick II., King of Denmark, having recognised Tycho Brahé’s great merits as an astronomer, and not wishing that his fame should add lustre to a foreign Court, expressed a desire that he should return to his native country, and as an inducement offered him a life interest in the island of Huen, in the Sound, where he undertook to erect and equip an observatory at his own expense; the King also promised to bestow upon him a pension, and grant him other emoluments besides.

Tycho gladly accepted this generous offer, and during the construction of the observatory occupied his time in making a magnificent collection of instruments and appliances adapted for observational purposes. This handsome edifice, upon which the King of Denmark expended a sum of 20,000l., was called ‘Uranienburg’ (‘The Citadel of the Heavens’). Here Tycho resided for a period of twenty years, during which time he pursued his astronomical labours with untiring energy and zeal, and made a large number of observations and calculations of much superior accuracy to any that existed previously, which were afterwards of great service to his successors. During his long residence at Huen, Tycho was visited by many distinguished persons, who were attracted to his island home by his fame and the magnificence of his observatory. Among them was James VI. of Scotland, who,[Pg 17] whilst journeying to the Court of Denmark on the occasion of his marriage to a Danish princess, paid Tycho a visit, and enjoyed his hospitality for a week. The King was delighted with all that he saw, and on his departure presented Tycho with a handsome donation, and at his request composed some Latin verses, in which he eulogised his host and praised his observatory.

The island of Huen is situated about six miles from the coast of Zealand, and fourteen from Copenhagen. It has a circumference of six miles, and consists chiefly of an elevated plateau, in the centre of which Tycho erected his observatory, the site of which is now marked by two pits and a few mounds of earth—all that remains of Uranienburg. All went well with Tycho Brahé during the lifetime of his noble patron; but in 1588 Frederick II. died, and was succeeded by his son, a youth eleven years of age.

The Danish nobles had long been jealous of Tycho’s fame and reputation, and on the death of the King an opportunity was afforded them of intriguing with the object of accomplishing his downfall. Several false accusations were brought against him, and the Court party made the impoverished state of the Treasury an excuse for depriving him of his pension and emoluments granted by the late King.

Tycho was no longer able to bear the expense of maintaining his establishment at Huen, and fearing that he might be deprived of the island itself,[Pg 18] he took a house in Copenhagen, to which he removed all his smaller instruments.

During his residence in the capital he was subjected to annoyance and persecution. An order was issued in the King’s name preventing him from carrying on his chemical experiments, and he besides suffered the indignity of a personal assault. Tycho Brahé resolved to quit his ungrateful country and seek a home in some foreign land, where he should be permitted to pursue his studies unmolested and live in quietness and peace. He accordingly removed from the island of Huen all his instruments and appliances that were of a portable nature, and packed them on board a vessel which he hired for the purpose of transport, and, having embarked with his family, his servants, and some of his pupils and assistants, ‘this interesting barque, freighted with the glory of Denmark,’ set sail from Copenhagen about the end of 1597, and having crossed the Baltic in safety, arrived at Rostock, where Tycho found some old friends waiting to receive him. He was now in doubt as to where he should find a home, when the Austrian Emperor Rudolph, himself a liberal patron of science and the fine arts, having heard of Tycho Brahé’s misfortunes, sent him an invitation to take up his abode in his dominions, and promised that he should be treated in a manner worthy of his reputation and fame.

Tycho resolved to accept the Emperor’s kind invitation, and in the spring of 1599 arrived at[Pg 19] Prague, where he found a handsome residence prepared for his reception.

He was received by the Emperor in a most cordial manner and treated with the greatest kindness. An annual pension of three thousand crowns was settled upon him for life, and he was to have his choice of several residences belonging to his Majesty, where he might reside and erect a new observatory. From among these he selected the Castle of Benach, in Bohemia, which was situated on an elevated plateau and commanded a wide view of the horizon.

During his residence at Benach Tycho received a visit from Kepler, who stayed with him for several months in order that he might carry out some astronomical observations. In the following year Kepler returned, and took up his permanent residence with Tycho, having been appointed assistant in his observatory, a post which, at Tycho’s request, was conferred upon him by the Emperor.

Tycho Brahé soon discovered that his ignorance of the language and unfamiliarity with the customs of the people caused him much inconvenience. He therefore asked permission from the Emperor to be allowed to remove to Prague. This request was readily granted, and a suitable residence was provided for him in the city.

In the meantime his family, his large instruments, and other property, having arrived at Prague, Tycho was soon comfortably settled in his new home.

[Pg 20] Though Tycho Brahé continued his astronomical observations, yet he could not help feeling that he lived among a strange people; nor did the remembrance of his sufferings and the cruel treatment he received at the hands of his fellow-countrymen subdue the affection which he cherished towards his native land. Pondering over the past, he became despondent and low-spirited; a morbid imagination caused him to brood over small troubles, and gloomy, melancholy thoughts possessed his mind—symptoms which seemed to presage the approach of some serious malady. One evening, when visiting at the house of a friend, he was seized with a painful illness, to which he succumbed in less than a fortnight. He died at Prague on October 24, 1601, when in his fifty-fifth year.

The Emperor Rudolph, when informed of Tycho Brahé’s death, expressed his deep regret, and commanded that he should be interred in the principal church in the city, and that his obsequies should be celebrated with every mark of honour and respect.

Tycho Brahé stands out as the most romantic and prominent figure in the history of astronomy. His independence of character, his ardent attachments, his strong hatreds, and his love of splendour, are characteristics which distinguish him from all other men of his age. This remarkable man was an astronomer, astrologer, and alchemist; but in his latter years he renounced astrology, and believed[Pg 21] that the stars exercised no influence over the destinies of mankind.

As a practical astronomer, Tycho Brahé has not been excelled by any other observer of the heavens. The magnificence of his observatory at Huen, upon the equipment and embellishment of which it is stated he expended a ton of gold; the splendour and variety of his instruments, and his ingenuity in inventing new ones, would alone have made him famous. But it was by the skill and assiduity with which he carried out his numerous and important observations that he has earned for himself a position of the most honourable distinction among astronomers. In his investigation of the Lunar theory Tycho Brahé discovered the Moon’s annual equation, a yearly effect produced by the Sun’s disturbing force as the Earth approaches or recedes from him in her orbit. He also discovered another inequality in the Moon’s motion, called the variation. He determined with greater exactness astronomical refractions from an altitude of 45° downwards to the horizon, and constructed a catalogue of 777 stars. He also made a vast number of observations on planets, which formed the basis of the ‘Rudolphine Tables,’ and were of invaluable assistance to Kepler in his investigation of the laws relating to planetary motion.

Tycho Brahé declined to accept the Copernican theory, and devised a system of his own, which he called the ‘Tychonic.’ By this arrangement the Earth remained stationary, whilst all the planets[Pg 22] revolved round the Sun, who in his turn completed a daily revolution round the Earth. All the phenomena associated with the motions of those bodies could be explained by means of this system; but it did not receive much support, and after the Copernican theory became better understood it was given up, and heard of no more.

We now arrive at the name of Kepler, one of the very greatest of astronomers, and a man of remarkable genius, who was the first to discover the real nature of the paths pursued by the Earth and planets in their revolution round the Sun. After seventeen years of close observation, he announced that those bodies travelled round the Sun in elliptical or oval orbits, and not in circular paths, as was believed by Copernicus. In his investigation of the laws which govern the motions of the planets he formulated those famous theorems known as ‘Kepler’s Laws,’ which will endure for all time as a proof of his sagacity and surpassing genius. Prior to the discovery of those laws the Sun, though acknowledged to be the centre of the system, did not appear to occupy a central position as regards the motions of the planets; but Kepler, by demonstrating that the planes of the orbits of all the planets, and the lines connecting their apsides, passed through the Sun, was enabled to assign the orb his true position with regard to those bodies.

John Kepler was born at Weil, in the Duchy of Wurtemberg, December 21, 1571. His parents, though of noble family, lived in reduced circumstances,[Pg 23] owing to causes for which they were themselves chiefly responsible. In his youth Kepler suffered so much from ill-health that his education had to be neglected. In 1586 he was sent to a monastic school at Maulbronn, which had been established at the Reformation, and was under the patronage of the Duke of Wurtemberg. Afterwards he studied at the University of Tubingen, where he distinguished himself and took a degree. Kepler devoted his attention chiefly to science and mathematics, but paid no particular attention to the study of astronomy. Maestlin, the professor of mathematics, whose lectures he attended, upheld the Copernican theory, and Kepler, who adopted the views of his teacher, wrote an essay in favour of the diurnal rotation of the Earth, in which he supported the more recent astronomical doctrines. In 1594, a vacancy having occurred in the professorship of astronomy at Gratz consequent upon the death of George Stadt, Kepler was appointed his successor. He did not seek this office, as he felt no particular desire to take up the study of astronomy, but was recommended by his tutors as a man well fitted for the post. He was thus in a manner compelled to devote his time and talents to the science of astronomy. Kepler directed his attention to three subjects—viz. ‘the number, the size, and the motion of the orbits of the planets.’ He endeavoured to ascertain if any regular proportion existed between the sizes of the planetary orbits, or in the difference of their sizes, but in this he was unsuccessful. He then thought[Pg 24] that, by imagining the existence of a planet between Mars and Jupiter, and another between Venus and Mercury, he might be able to attain his object; but he found that this assumption afforded him no assistance. Kepler then imagined that as there were five regular geometrical solids, and five planets, the distances of the latter were regulated by the size of the solids described round one another. The discovery afterwards of two additional planets testified to the absurdity of this speculation. A description of these extraordinary researches was published, in 1596, in a work entitled ‘Prodromus of Cosmographical Dissertations; containing the cosmographical mystery respecting the admirable proportion of the celestial orbits, and the genuine and real causes of the number, magnitude, and periods of the planets, demonstrated by the five regular geometrical solids.’ This volume, notwithstanding the fanciful speculations which it contained, was received with much favour by astronomers, and both Tycho Brahé and Galileo encouraged Kepler to continue his researches. Galileo admired his ingenuity, and Tycho advised him ‘to lay a solid foundation for his views by actual observation, and then, by ascending from these, to strive to reach the causes of things.’ Kepler spent many years in these fruitless endeavours before he made those grand discoveries in search of which he laboured so long.

The religious dissensions which at this time agitated Germany were accompanied in many places by much tumult and excitement. At Gratz[Pg 25] the Catholics threatened to expel the Protestants from the city. Kepler, who was of the Reformed faith, having recognised the danger with which he was threatened, retired to Hungary with his wife, whom he had recently married, and remained there for near twelve months, during which time he occupied himself with writing several short treatises on subjects connected with astronomy. In 1599 he returned to Gratz and resumed his professorship.

In the year 1600 Kepler set out to pay Tycho Brahé a visit at Prague, in order that he might be able to avail himself of information contained in observations made by Tycho with regard to the eccentricities of the orbits of the planets. He was received by Tycho with much cordiality, and stayed with him for four months at his residence at Benach, Tycho in the meantime having promised that he would use his influence with the Emperor Rudolph to have him appointed as assistant in his observatory. On the termination of his visit Kepler returned to Gratz, and as there was a renewal of the religious trouble in the city, he resigned his professorship, from which he only derived a small income, and, relying on Tycho’s promise, he again journeyed to Prague, and arrived there in 1601. Kepler was presented to the Emperor by Tycho, and the post of Imperial Mathematician was conferred upon him, with a salary of 100 florins a year, upon condition that he should assist Tycho in his observatory. This appointment was of much value to[Pg 26] Kepler, because it afforded him an opportunity of obtaining access to the numerous astronomical observations made by Tycho, which were of great assistance to him in the investigation of the subject which he had chosen—viz. the laws which govern the motions of the planets, and the form and size of the planetary orbits.

As an acknowledgment of the Emperor’s great kindness, the two astronomers resolved to compute a new set of astronomical tables, and in honour of his Majesty they were to be called the ‘Rudolphine Tables.’ This project pleased the Emperor, who promised to defray the expense of their publication. Logomontanus, Tycho’s chief assistant, had entrusted to him that portion of the work relating to observations on the stars, and Kepler had charge of the part which embraced the calculations belonging to the planets and their orbits. This important work had scarcely been begun when the departure of Logomontanus, who obtained an appointment in Denmark, and the death of Tycho Brahé in October 1601, necessitated its suspension for a time. Kepler was appointed Chief Mathematician to the Emperor in succession to Tycho—a position of honour and distinction, and to which was attached a handsome salary, that was paid out of the Imperial treasury. But owing to the continuance of expensive wars, which entailed a severe drain upon the resources of the country, the public funds became very low, and Kepler’s salary was always in arrear. This condition of things involved him in serious pecuniary[Pg 27] difficulties, and the responsibility of having to maintain an increasing family added to his anxieties. It was with the greatest difficulty that he succeeded in obtaining payment of even a portion of his salary, and he was reduced to such straits as to be under the necessity of casting nativities in order to obtain money to meet his most pressing requirements.

In 1609 Kepler published his great work, entitled ‘The New Astronomy; or, Commentaries on the Motions of Mars.’ It was by his observation of Mars, which has an orbit of greater eccentricity than that of any of the other planets, with the exception of Mercury, that he was enabled, after years of patient study, to announce in this volume the discovery of two of the three famous theorems known as Kepler’s Laws. The first is, that all the planets move round the Sun in elliptic orbits, and that the orb occupies one of the foci. The second is, that the radius-vector, or imaginary line joining the centre of the planet and the centre of the Sun, describes equal areas in equal times. The third law, which relates to the connection between the periodic times and the distances of the planets, was not discovered until ten years later, when Kepler, in 1619, issued another work, called the ‘Harmonies of the World,’ dedicated to James I. of England, in which was contained this remarkable law. These laws have elevated astronomy to the position of a true physical science, and also formed the starting-point of Newton’s investigations which led to the discovery of[Pg 28] the law of gravitation. Kepler’s delight on the discovery of his third law was unbounded. He writes: ‘Nothing holds me. I will indulge in my sacred fury. I will triumph over mankind by the honest confession that I have stolen the golden vases of the Egyptians to build up a tabernacle for my God far away from the confines of Egypt. If you forgive me, I rejoice; if you are angry, I can bear it. The die is cast; the book is written, to be read either now or by posterity I care not which. It may well wait a century for a reader, as God has waited six thousand years for an observer.’

When Kepler presented his celebrated book to the Emperor, he remarked that it was his intention to make a similar attack upon the other planets, and promised that he would be successful if his Majesty would undertake to find the means necessary for carrying on operations. But the Emperor had more formidable enemies to contend with nearer home than Jupiter and Saturn, and no funds were forthcoming to assist Kepler in his undertaking.

The chair of mathematics in the University of Linz having become vacant, Kepler offered himself as a candidate for the appointment, which he was anxious to obtain; but the Emperor Rudolph was averse to his leaving Prague, and encouraged him to hope that the arrears of his salary would be paid. But past experience led Kepler to have no very sanguine expectations on this point; nor was it until after the death of Rudolph, in 1612, that he was relieved from his pecuniary embarrassments.

[Pg 29] On the accession of Rudolph’s brother, Matthias, to the Austrian throne, Kepler was reappointed Imperial Mathematician; he was also permitted to hold the professorship at Linz, to which he had been elected. Kepler was not loth to remove from Prague, where he had spent eleven years harassed by poverty and other domestic afflictions. Having settled with his family at Linz, Kepler issued another work, in 1618, entitled ‘Epitome of the Copernican Astronomy,’ in which he gave a general account of his astronomical observations and discoveries, and a summary of his opinions with regard to the theories which in those days were the subject of controversial discussion. Almost immediately after its publication it was included by the Congregation of the Index, at Rome, in the list of prohibited books. This occasioned Kepler considerable alarm, as he imagined it might interfere with the sale of his works, or give rise to difficulties in the issue of others. He, however, was assured by his friend Remus that the action of the Papal authorities need cause him no anxiety.

The Emperor Matthias died in 1619, and was succeeded by Ferdinand III., who not only retained Kepler in his office, but gave orders that all the arrears of his salary should be paid, including those which accumulated during the reign of Rudolph; he also expressed a desire that the ‘Rudolphine Tables’ should be published without delay and at his cost. But other obstacles intervened, for at this time Germany was involved in a civil and religious[Pg 30] war, which interfered with all peaceful vocations. Kepler’s library at Linz was sealed up by order of the Jesuits, and the city was for a time besieged by troops. This state of public affairs necessitated a considerable delay in the publication of the ‘Tables.’

The ‘Rudolphine Tables’ were published at Ulm in 1627. They were commenced by Tycho Brahé, and completed by Kepler, who made his calculations from Tycho’s observations, and based them upon his own great discovery of the ellipticity of the orbits of the planets. They are divided into four parts. The first and third parts contain logarithmic and other tables for the purpose of facilitating astronomical calculations; in the second are tables of the Sun, Moon, and planets; and in the fourth are indicated the positions of one thousand stars as determined by Tycho. Kepler made a special journey to Prague in order to present the ‘Tables’ to the Emperor, and afterwards the Grand Duke of Tuscany sent him a gold chain as an acknowledgment of his appreciation of the completion of this great work.

Albert Wallenstein, Duke of Friedland, an accomplished scholar and a man fond of scientific pursuits, made Kepler a most liberal offer if he would take up his residence in his dominions. After duly considering this proposal, Kepler decided to accept the Duke’s offer, provided it received the sanction of the Emperor. This was readily given, and Kepler, in 1629, removed with his family from Linz to Sagan, in Silesia. The Duke of Friedland[Pg 31] treated him with great kindness and liberality, and through his influence he was appointed to a professorship in the University of Rostock. Though Kepler was permitted to retain the pension bestowed upon him by the late Emperor Rudolph, he was unable after his removal to Silesia to obtain payment of it, and there was a large accumulation of arrears. In a final endeavour to recover the amount owing to him he travelled to Ratisbon, and appealed to the Imperial Assembly, but without success. The fatigue which Kepler endured on his journey, combined with vexation and disappointment, brought on a fever, which terminated fatally. He died on November 15, 1630, when in the sixtieth year of his age, and was interred in St. Peter’s churchyard, Ratisbon.

Kepler was a man of indomitable energy and perseverance, and spared neither time nor trouble in the accomplishment of any object which he took in hand. In thinking over the form of the orbits of the planets, he writes: ‘I brooded with the whole energy of my mind on this subject—asking why they are not other than they are—the number, the size, and the motions of the orbits.’ But many fanciful ideas passed through Kepler’s imaginative brain before he hit upon the true form of the planetary orbits. In his ‘Mysterium Cosmographicum’ he asserts that the five kinds of regular polyhedral solids, when described round one another, regulated the distances of the planets and size of the planetary orbits. In support of this theory he[Pg 32] writes as follows: ‘The orbit of the Earth is the measure of the rest. About it circumscribe a dodecahedron. The sphere including this will be that of Mars. About Mars’ orbit describe a tetrahedron; the sphere containing this will be Jupiter’s orbit. Round Jupiter’s describe a cube; the sphere including this will be Saturn’s. Within the Earth’s orbit inscribe an icosahedron; the sphere inscribed in it will be Venus’s orbit. In Venus inscribe an octahedron; the sphere inscribed in it will be Mercury’s.’

The above quotation is an instance of Kepler’s wild and imaginative genius, which ultimately led him to make those sublime discoveries associated with planetary motion which are known as ‘Kepler’s Laws.’

He describes himself as ‘troublesome and choleric in politics and domestic matters;’ but in his relations with scientific men he was affable and pleasant. He showed no jealousy of a rival, and was always ready to recognise merit in others; nor did he hesitate to acknowledge any error of his own when more recent discoveries proved that he was wrong.

Some of his works contain passages, written in a jocular strain, indicative of a bright and cheerful temperament. The following characteristic paragraph refers to the opinions of the Epicureans with regard to the appearance of a new star, which they ascribed to a fortuitous concourse of atoms: ‘When I was a youth, with plenty of idle time on[Pg 33] my hands, I was much taken with the vanity, of which some grown men are not ashamed, of making anagrams by transposing the letters of my name written in Latin so as to make another sentence. Out of Ioannes Keplerus came Serpens in akuleo (a serpent in his sting); but not being satisfied with the meaning of these words, and being unable to make another, I trusted the thing to chance, and, taking out of a pack of playing-cards as many as there were letters in the name, I wrote one upon each, and then began to shuffle them, and at each shuffle to read them in the order they came, to see if any meaning came of it. Now, may all the Epicurean gods and goddesses confound this same chance, which, although I have spent a good deal of time over it, never showed me anything like sense, even from a distance. So I gave up my cards to the Epicurean eternity, to be carried away into infinity; and it is said they are still flying about there, in the utmost confusion, among the atoms, and have never yet come to any meaning. I will tell those disputants, my opponents, not my own opinion, but my wife’s. Yesterday, when weary with writing, and my mind quite dusty with considering these atoms, I was called to supper, and a salad I had asked for was set before me. “It seems, then,” said I aloud, “that if pewter dishes, leaves of lettuce, grains of salt, drops of water, vinegar and oil, and slices of egg, had been flying about in the air from all eternity, it might at last happen by chance that there would come a salad.” [Pg 34] “Yes,” says my wife, “but not so nice and well dressed as this of mine is.”‘

Notwithstanding the frequent interruptions which, owing to various reasons, retarded his labours, Kepler was able to bring to a successful completion the numerous and important works upon which he was engaged during his lifetime, the voluminous nature of which may be imagined when it is stated that he published thirty-three separate works, besides leaving behind twenty-two volumes of manuscript.

During his researches on the motions of Mars, Kepler discovered that the planet sometimes travelled at an accelerated rate of speed, and at another time its pace was diminished. At one time he observed it to be in advance of the place where he calculated it should be found, and at another time it was behind it. This caused him considerable perplexity, and, feeling convinced in his mind that the form of the planet’s orbit could not be circular, he was compelled to turn his attention to some other closed curve, by which those inequalities of motion could be explained.

After years of careful observation and study, Kepler arrived at the conclusion that the form of the planet’s orbit is an ellipse, and that the Sun occupies one of the foci. He afterwards determined that the orbits of all the planets are of an elliptical form.

Having discovered the true form of the planetary orbits, Kepler next endeavoured to ascertain the[Pg 35] cause which regulates the unequal motion that a planet pursues in its path. He observed that when a planet approached the Sun its motion was accelerated, and as it receded from him its pace became slower.

This he explained in his next great discovery by proving that an imaginary line, or radius-vector, extending from the centre of the Sun to the centre of the planet ‘describes equal areas in equal times.’ When near the Sun, or at perihelion, a planet traverses a larger portion of its arc in the same period of time than it does when at the opposite part of its orbit, or when at aphelion; but, as the areas of both are equal, it follows that the planet does not always maintain the same rate of speed, and that its velocity is greatest when nearest the Sun, and least when most distant from him.

By the application of his first and second laws Kepler was able to formulate a third law. He found that there existed a remarkable relationship between the mean distances of the planets and the times in which they complete their revolutions round the Sun, and discovered ‘that the squares of the periodic times are to each in the same proportion as the cubes of the mean distances.’ The periodic time of a planet having been ascertained, the square of the mean distance and the mean distance itself can be obtained. It is by the application of this law that the distances of the planets are usually calculated.

[Pg 36] These discoveries are known as Kepler’s Laws, and are usually classified as follows:—

1. ‘The orbit described by every planet is an ellipse, of which the centre of the Sun occupies one of the foci.

2. ‘Every planet moves round the Sun in a plane orbit, and the radius-vector, or imaginary line joining the centre of the planet and the centre of the Sun, describes equal areas in equal times.

3. ‘The squares of the periodic times of any two planets are proportional to the cubes of their mean distances from the Sun.’[1]

These remarkable discoveries do not embrace all the achievements by which Kepler has immortalised his name, and earned for himself the proud title of ‘Legislator of the Heavens;’ he predicted transits of Mercury and Venus, made important discoveries in optics, and was the inventor of the astronomical telescope.

Galileo Galilei, the famous Italian astronomer and philosopher, and the contemporary of Kepler and of Milton, was born at Pisa on February 15, 1564.

His father, who traced his descent from an ancient Florentine family, was desirous that his son should adopt the profession of medicine, and with this intention he entered him as a student at the University of Pisa. Galileo, however, soon discovered that the study of mathematics and mechanical science possessed a greater attraction[Pg 37] for his mind, and, following his inclinations, he resolved to devote his energies to acquiring proficiency in those subjects.

In 1583 his attention was attracted by the oscillation of a brass lamp suspended from the ceiling of the cathedral at Pisa. Galileo was impressed with the regularity of its motion as it swung backwards and forwards, and was led to imagine that the pendulum movement might prove a valuable method for the correct measurement of time. The practical application of this idea he afterwards adopted in the construction of an astronomical clock.

Having become proficient in mathematics, Galileo, whilst engaged in studying the writings of Archimedes, wrote an essay on ‘The Hydrostatic Balance,’ and composed a treatise on ‘The Centre of Gravity in Solid Bodies.’ The reputation which he earned by these contributions to science procured for him the appointment of Lecturer on Mathematics at the University of Pisa. Galileo next directed his attention to the works of Aristotle, and made no attempt to conceal the disfavour with which he regarded many of the doctrines taught by the Greek philosopher; nor had he any difficulty in exposing their inaccuracies. One of these, which maintained that the heavier of two bodies descended to the earth with the greater rapidity, he proved to be incorrect, and demonstrated by experiment from the top of the tower at Pisa that, except for the unequal resistance of the air, all bodies fell to the ground with the same velocity.

[Pg 38] As the chief expounder of the new philosophy, Galileo had to encounter the prejudices of the followers of Aristotle, and of all those who disliked any innovation or change in the established order of things. The antagonism which existed between Galileo and his opponents, who were both numerous and influential, was intensified by the bitterness and sarcasm which he imparted into his controversies, and the attitude assumed by his enemies at last became so threatening that he deemed it prudent to resign the Chair of Mathematics in the University of Pisa.

In the following year he was appointed to a similar post at Padua, where his fame attracted crowds of pupils from all parts of Europe.

In 1611 Galileo visited Rome. He was received with much distinction by the different learned societies, and was enrolled a member of the Lyncæan Academy. In two years after his visit to the capital he published a work in which he declared his adhesion to the Copernican theory, and openly avowed his disbelief in the astronomical facts recorded in the Scriptures. Galileo maintained that the sacred writings were not intended for the purpose of imparting scientific information, and that it was impossible for men to ignore phenomena witnessed with their eyes, or disregard conclusions arrived at by the exercise of their reasoning powers.

The champions of orthodoxy having become alarmed, an appeal was made to the ecclesiastical[Pg 39] authorities to assist in suppressing this recent astronomical heresy, and other obnoxious doctrines, the authorship of which was ascribed to Galileo.

In 1615, Galileo was summoned before the Inquisition to reply to the accusation of heresy. ‘He was charged with maintaining the motion of the Earth and the stability of the Sun; with teaching this doctrine to his pupils; with corresponding on the subject with several German mathematicians; and with having published it, and attempted to reconcile it to Scripture in his letters to Mark Velser in 1612.’

These charges having been formally investigated by the Inquisition, Cardinal Bellarmine was authorised to communicate with Galileo, and inform him that unless he renounced the obnoxious doctrines, and promised ‘neither to teach, defend, or publish them in future,’ it was decreed that he should be committed to prison. Galileo appeared next day before the Cardinal, and, without any hesitation, pledged himself that for the future he would adhere to the pronouncement of the Inquisition.

Having, as they imagined, silenced Galileo, the Inquisition resolved to condemn the entire Copernican system as heretical; and in order to effectually accomplish this, besides condemning the writings of Galileo, they inhibited Kepler’s ‘Epitome of the Copernican System,’ and Copernicus’s own work, ‘De Revolutionibus Orbium Celestium.’

Whether it was that Galileo regarded the Inquisition as a body whose decrees were too[Pg 40] absurd and unreasonable to be heeded, or that he dreaded the consequences which might have followed had he remained obstinate, we know that, notwithstanding the pledges which he gave, he was soon afterwards engaged in controversial discussion on those subjects which he promised not to mention again.

On the accession of his friend Cardinal Barberini to the pontifical throne in 1623, under the title of Urban VIII., Galileo undertook a journey to Rome to offer him his congratulations upon his elevation to the papal chair. He was received by his Holiness with marked attention and kindness, was granted several prolonged audiences, and had conferred upon him several valuable gifts.

Notwithstanding the kindness of Pope Urban and the leniency with which he was treated by the Inquisition, Galileo, having ignored his pledge, published in 1632 a book, in dialogue form, in which three persons were supposed to express their scientific opinions. The first upheld the Copernican theory and the more recent philosophical views; the second person adopted a neutral position, suggested doubts, and made remarks of an amusing nature; the third individual, called Simplicio, was a believer in Ptolemy and Aristotle, and based his arguments upon the philosophy of the ancients.

As soon as this work became publicly known, the enemies of Galileo persuaded the Pope that the third person held up to ridicule was intended as a representation of himself—an individual[Pg 41] regardless of scientific truth, and firmly attached to the ideas and opinions associated with the writings of antiquity.

Almost immediately after the publication of the ‘Dialogues’ Galileo was summoned before the Inquisition, and, notwithstanding his feeble health and the infirmities of advanced age, he was, after a long and tedious trial, condemned to abjure by oath on his knees his scientific beliefs.

‘The ceremony of Galileo’s abjuration was one of exciting interest and of awful formality. Clothed in the sackcloth of a repentant criminal, the venerable sage fell upon his knees before the assembled cardinals, and, laying his hand upon the Holy Evangelists, he invoked the Divine aid in abjuring, and detesting, and vowing never again to teach the doctrines of the Earth’s motion and of the Sun’s stability. He pledged himself that he would nevermore, either in words or in writing, propagate such heresies; and he swore that he would fulfil and observe the penances which had been inflicted upon him.’ ‘At the conclusion of this ceremony, in which he recited his abjuration word for word and then signed it, he was conveyed, in conformity with his sentence, to the prison of the Inquisition.’[2]

Galileo’s sarcasm, and the bitterness which he imparted into his controversies, were more the cause of his misfortunes than his scientific beliefs. When he became involved in difficulties he did not possess the moral courage to enable him to abide[Pg 42] by the consequences of his acts; nor did he care to become a martyr for the sake of science, his submission to the Inquisition having probably saved him from a fate similar to what befell Bruno. Though it would be impossible to justify Galileo’s want of faith in his dealings with the Inquisition, yet one cannot help sympathising deeply with the aged philosopher, who, in this painful episode of his life, was compelled to go through the form of making a retractation of his beliefs under circumstances of a most humiliating nature.

But the persecution of Galileo did not delay the progress of scientific inquiry nor retard the advancement of the Copernican theory, which, after the discovery by Newton of the law of gravitation, was universally adopted as the true theory of the solar system.

Ferdinand, Duke of Tuscany, having exerted his influence with Pope Urban on behalf of Galileo, he was, after a few days’ incarceration, released from prison, and permission was given him to reside at Siena, where he remained for six months. He was afterwards allowed to return to his villa at Arcetri, and, though regarded as a prisoner of the Inquisition, was permitted to pursue his studies unmolested for the remainder of his days.

Galileo died at Arcetri on January 8, 1642, when in the seventy-eighth year of his age.

Though not the inventor, he was the first to construct a refracting telescope and apply it to astronomical research. With this instrument he[Pg 43] made a number of important discoveries which tended to confirm his belief in the truthfulness of the Copernican theory.

On directing his telescope to the Sun, he discovered movable spots on his disc, and concluded from his observation of them that the orb rotated on his axis in about twenty-eight days. He also ascertained that the Moon’s illumination is due to reflected sunlight, and that her surface is diversified by mountains, valleys, and plains.

On the night of January 7, 1610, Galileo discovered the four moons of Jupiter. This discovery may be regarded as one of his most brilliant achievements with the telescope; and, notwithstanding the improvement in construction and size of modern instruments, no other satellite was discovered until near midnight on September 9, 1892, when Mr. E. E. Barnard, with the splendid telescope of the Lick Observatory, added ‘another gem to the diadem of Jupiter.’

The phases of Venus and Mars, the triple form of Saturn, and the constitution of the Milky Way, which he found to consist of a countless multitude of stars, were additional discoveries for our knowledge of which we are indebted to Galileo and his telescope. Galileo made many other important discoveries in mechanical and physical science. He detected the law of falling bodies in their accelerated motion towards the Earth, determined the parabolic law of projectiles, and demonstrated[Pg 44] that matter, even if invisible, possessed the property of weight.

In these pages a short historical description is given of the progress made in astronomical science from an early period to the time in which Milton lived. The discoveries of Copernicus, Kepler, and Galileo had raised it to a position of lofty eminence, though the law of gravitation, which accounts for the form and permanency of the planetary orbits, still remained undiscovered. Theories formerly obscure or conjectural were either rejected or elucidated with accuracy and precision, and the solar system, having the Sun as its centre, with his attendant family of planets and their satellites revolving in majestic orbits around him, presented an impressive spectacle of order, harmony, and design.

The seventeenth century embraces the most remarkable epoch in the whole history of astronomy. It was during this period that those wonderful discoveries were made which have been the means of raising astronomy to the lofty position which it now occupies among the sciences. The unrivalled genius and patient labours of the illustrious men whose names stand out in such prominence on the written pages of the history of this era have rendered it one of the most interesting and elevating of studies. Though Copernicus lived in the preceding century, yet the names of Tycho Brahé, Kepler, Galileo, and Newton, testify to the greatness of the discoveries that were made during this period, which have surrounded the memories of those men with a lustre of undying fame.

Foremost among astronomers of less conspicuous eminence who made important discoveries in this century we find the name of Huygens.

Christian Huygens was born at The Hague in 1629. He was the second son of Constantine Huygens, an eminent diplomatist, and secretary to the Prince of Orange. Huygens studied at Leyden[Pg 46] and Breda, and became highly distinguished as a geometrician and scientist. He made important investigations relative to the figure of the Earth, and wrote a learned treatise on the cause of gravity; he also determined with greater accuracy investigations made by Galileo regarding the accelerated motion of bodies when subjected to the influence of that force.

Huygens admitted that the planets and their satellites attracted each other with a force varying according to the inverse ratio of the squares of their distances, but rejected the mutual attraction of the molecules of matter, believing that they possessed gravity towards a central point only, to which they were attracted. This supposition was at variance with the Newtonian theory, which, however, was universally regarded as the correct one.

Huygens originated the theory by which it is believed that light is produced by the undulatory vibration of the ether; he also discovered polarization.

Up to this time the method adopted in the construction of clocks was not capable of producing a mechanism which measured time with sufficient accuracy to satisfy the requirements of astronomers. Huygens endeavoured to supply this want, and applied his mechanical ingenuity in constructing a clock that could be relied upon to keep accurate time. Though the pendulum motion was first adopted by Galileo, he was unable to arrange its mechanism so that it should keep up a continuous movement. The oscillation of the pendulum ceased[Pg 47] after a time, and a fresh impulse had to be applied to set it in motion. Consequently, Galileo’s clock was of no service as a timekeeper.

Huygens overcame this difficulty by so arranging the mechanism of his clock that the balance, instead of being horizontal, was directed perpendicularly, and prolonged downwards to form a pendulum, the oscillations of which regulated the downward motion of the weight. This invention, which was highly applauded, proved to be of great service everywhere, and was especially valuable for astronomical purposes.

Huygens next directed his attention to the construction of telescopes, and displayed much skill in the grinding and polishing of lenses. He made several instruments superior in power and accuracy to any that existed previously, and with one of these made some remarkable discoveries when observing the planet Saturn.

The telescopic appearance of Saturn is one of the most beautiful in the heavens. The planet, surrounded by two brilliant rings, and accompanied by eight attendant moons, surpasses all the other orbs of the firmament as an object of interest and admiration. To the naked eye, Saturn is visible as a star of the first magnitude, and was known to the ancients as the most remote of the planets. Travelling in space at a distance of nearly one thousand millions of miles from the Sun, the planet accomplishes a revolution of its mighty orbit in twenty-nine and a half years.

Galileo was the first astronomer who directed a[Pg 48] telescope to Saturn. He observed that the planet presented a triform appearance, and that on each side of the central globe there were two objects, in close contact with it, which caused it to assume an ovoid shape. After further observation, Galileo perceived that the lateral bodies gradually decreased in size, until they became invisible. At the expiration of a certain period of time they reappeared, and were observed to go through a certain cycle of changes. By the application of increased telescopic power it was discovered that the appendages were not of a rounded form, but appeared as two small crescents, having their concave surfaces directed towards the planet and their extremities in contact with it, resembling the manner in which the handles are attached to a cup.

These objects were observed to go through a series of periodic changes. After having become invisible, they reappeared as two luminous straight bands, projecting from each side of the planet; during the next seven or eight years they gradually opened out, and assumed a crescentic form; they afterwards began to contract, and on the expiration of a similar period, during which time they gradually decreased in size, they again became invisible. It was perceived that the appendages completed a cycle of their changes in about fifteen years.

In 1656, Huygens, with a telescope constructed by himself, was enabled to solve the enigma which for so many years baffled the efforts of the ablest astronomers. He announced his discovery in the form[Pg 49] of a Latin cryptograph which, when deciphered, read as follows:—

‘Annulo cingitur, tenui plano, nusquam cohaerente, ad eclipticam inclinatio.’

‘The planet is surrounded by a slender flat ring everywhere distinct from its surface, and inclined to the ecliptic.’

Huygens perceived the shadow of the ring thrown on the planet, and was able to account in a satisfactory manner for all the phenomena observed in connection with its variable appearance.

The true form of the ring is circular, but by us it is seen foreshortened; consequently, when the Earth is above or below its plane, it appears of an elliptical shape. When the position of the planet is such that the plane of the ring passes through the Sun, the edge of the ring only is illumined, and then it becomes invisible for a short period. In the same manner, when the plane of the ring passes through the Earth, the illumined edge of the ring is not of sufficient magnitude to appear visible, but as the enlightened side of the plane becomes more inclined towards the Earth, the ring comes again into view. When the plane of the ring passes between the Earth and the Sun, the unillumined side of the ring is turned towards the Earth, and during the time it remains in this position it is invisible.

Huygens discovered the sixth satellite of Saturn (Titan), and also the Great Nebula in Orion.

Johann Hevelius, a celebrated Prussian astronomer, was born at Dantzig in 1611, and died in[Pg 50] that city in 1687. He was a man of wealth, and erected an observatory at his residence, where, for a period of forty years, he carried out a series of astronomical observations.

He constructed a chart of the stars, and in order to complete his work, formed nine new constellations in those spaces in the celestial vault which were previously un-named. They are known by the names Camelopardus, Canes Venatici, Coma Bernices, Lacerta, Leo Minor, Lynx, Monoceros, Sextans, and Vulpecula. He also executed a chart of the Moon’s surface, wrote a description of the lunar spots, and discovered the Libration of the Moon in Longitude.

On May 30, 1661, Hevelius observed a transit of Mercury, a description of which he published, and included with it Horrox’s treatise on the first-recorded transit of Venus. This work, after having passed through several hands, became the property of Hevelius, who was capable of appreciating its merits. The manuscript was sent to him by Huygens, and in acknowledging it he writes: ‘How greatly does my Mercury exult in the joyous prospect that he may shortly fold within his arms Horrox’s long looked-for and beloved Venus! He renders you unfeigned thanks that by your permission this much-desired union is about to be celebrated, and that the writer is able, with your concurrence, to introduce them both together to the public.’

Hevelius made numerous researches on comets,[Pg 51] and suggested that the form of their paths might be a parabola.

Giovanni Domenico Cassini was born at Perinaldo, near Nice, in 1625. He studied at Genoa and Bologna, and was afterwards appointed to the Chair of Astronomy at the latter University. He was a man of high scientific attainments, and made many important astronomical discoveries.

In 1671 he became Director of the Royal Observatory at Paris, and devoted a long life to trying and difficult observations, which in his later years deprived him of his eyesight.

In 1644 Cassini proved beyond doubt that Jupiter rotated on his axis, and also assigned his period of rotation with considerable accuracy. He published tables of the planet’s satellites, and determined their motions from observations of their eclipses. He ascertained the periods of rotation of Venus and Mars; executed a chart of the lunar surface, and observed an occultation of Jupiter by the Moon.

Cassini discovered the dual nature of Saturn’s ring, having perceived that instead of one there are two concentric rings separated by a dark space. He also discovered four of the planet’s satellites—viz. Japetus, Rhea, Dione, and Tethys. He made a near approximation to the solar parallax by means of researches on the parallax of Mars, and investigated some irregularities of the Moon’s motion. Cassini discovered the belts of Jupiter, and also the[Pg 52] Zodiacal Light, and established the coincidence of the nodes of the lunar equator and orbit.

Jaques Cassini, son of Giovanni, was born at Paris in 1677. He followed in his father’s footsteps, and wrote several treatises on astronomical subjects. He investigated the period of the rotation of Venus on her axis, and upheld the results arrived at by his father, which were afterwards confirmed by observations made by Schroeter. Cassini made some valuable researches with regard to the proper motion of the stars, and demonstrated that their change of position on the celestial vault was real, and not caused by a displacement of the ecliptic. He attempted to ascertain the apparent diameter of Sirius, and made observations with regard to the visibility of the stars. The Cassini family produced several generations of eminent astronomers, whose discoveries and investigations were of much value in advancing the science of astronomy.

Olaus Roemer, an eminent Danish astronomer, was born at Copenhagen September 25, 1644. When Picard, a French astronomer, visited Denmark in 1671, for the purpose of ascertaining the exact position of ‘Uranienburg,’ the site of Tycho Brahé’s observatory, he made the acquaintance of Roemer, who was engaged in studying mathematics and astronomy under Erasmus Bartolinus. Having perceived that the young man was gifted with no ordinary degree of talent, he secured his services to assist him in his observations, and, on the conclusion[Pg 53] of his labours, Picard was so much impressed with the ability displayed by Roemer, that he invited him to accompany him to France. This invitation he accepted, and took up his residence in the French capital, where he continued to prosecute his astronomical studies.

In 1675 Roemer communicated to the Academy of Sciences a paper, in which he announced his discovery of the progressive transmission of light. It was believed that light travelled instantaneously, but Roemer was able to demonstrate the inaccuracy of this conclusion, and determined that light travels through space with a measurable velocity.