The Project Gutenberg EBook of Shoulder-Straps, by Henry Morford

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Shoulder-Straps

A Novel of New York and the Army, 1862

Author: Henry Morford

Release Date: August 3, 2009 [EBook #29583]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SHOULDER-STRAPS ***

Produced by David Edwards, Graeme Mackreth and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

T.B. Peterson & Bros.

PHILADELPHIA.

PHILADELPHIA:

T.B. PETERSON & BROTHERS,

306 CHESTNUT STREET.

Entered according to Act of Congress in the year 1863, by

T.B. PETERSON & BROTHERS,

In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the United States,

in and for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania.

THE AUTHOR.

New York City, July, 1863.

Several months have necessarily elapsed since the commencement of this narration. Within that time many and rapid changes have occurred, both in national situation and in private character. As a consequence, there may be several words, in earlier portions of the story, that would not have been written a few months later. The writer has preferred not to make any changes in original expression, but to set down, instead, in references, the dates at which certain portions of the work were written. In one instance important assistance has been derived from a writer of ability and much military experience; and that assistance is thankfully acknowledged in a foot-note to one of the appropriate chapters. Some readers may be disappointed not to find a work more extensively military, under such a title and at this time; but the aim of the writer, while giving glances at one or two of our most important battles, has been chiefly to present a faithful picture of certain relations in life and society which have grown out, as side-issues, from the great struggle. At another time and under different circumstances, the writer might feel disposed to apologize for the great liberty of episode and digression, taken with the story; but in the days of Victor Hugo and Charles Reade, and at a time when the text of the preacher in his pulpit, and the title of a bill in a legislative body, are alike made the threads upon which to string the whole knowledge of the speaker upon every subject,—such an apology can scarcely be necessary. It should be said, in deference to a few retentive memories, that two chapters of this story, now embraced in the body of the work, were originally written for and published in the Continental Monthly, last fall, the publication of the whole work through that medium, at first designed, being prevented by a change of management and a contract mutually broken.

New York City, July, 1863.

Two Friends—Walter Lane Harding and Tom Leslie—Merchant and Journalist—A Torn Dress and a Stalwart Champion—Tom Leslie's Story of Dexter Ralston—Three Meetings—An Incident on the Potomac—The Inauguration of Lincoln—A Warning of the Virginia Secession—Governmental Blindness—Friend or Foe to the Union?

Richard Crawford and Josephine Harris—The Invalid and the Wild Madonna—An Odd Female Character and a Temptation—Discouragement and Consolation—Miss Joe Harris on the Character of Colonel Egbert Crawford—A Suggestion of Hatred and Murder—A New Agony for the Invalid—A Lady with an Attachment to Cerise Ribbon.

A Scene at Judge Owen's—Mother and Daughter—Pretty Emily with One Lover Too Many—Emily's Determination, and Judge Owen's Ultimatum—A Pompous Judge playing Grand Signeur in his own Family—Aunt Martha to the Rescue—Her Story of Marriage without Love, Wedded Misery and Outrage—How Old is Colonel John Boadley Bancker, and what is the Character of Frank Wallace?

Harding and Leslie make Discoveries on Prince Street—Secesh Flags and Emblems of the Golden Circle—What do they mean?—Tom Leslie takes a Climb and a Tumble—The Red Woman—A Carriage Chase Up-town—A Mysterious House—Amateur Detectives under a Door-step, and what they saw and heard.

Who was the Red Woman?—Tom Leslie's Strange Story of Parisian Life and Fortune-telling—The 20th of December, 1860—An Hour in the Rue la Reynie Ogniard—The Vision of the White Mist—The Secession of South Carolina seen across the Atlantic—Was the Sorceress in America?

Colonel Egbert Crawford and Miss Bell Crawford—Miss Harris entering upon the Spy-System—Some Dissertations thereon, as practised in the Army and Elsewhere—What McDowell knew before Bull Run—Colonel Crawford's Affectionate Care of his Sick Cousin—Josephine Harris behind a Glass Door—What she overheard about Cousin Mary and the Rich Uncle at West Falls—Colonel Crawford trying his Hand at Doctoring—A Suspicious Bandage, and what the Watcher thought of it

Introduction of the Contraband—What He Was and What He Is—Three Months Earlier—Colonel Egbert Crawford in Thomas Street—Aunt Synchy, the Obi Woman—How a Man who is only half evil can be tempted to murder—The Black Paste of the Obi Poison

Colonel John Boadley Bancker and Frank Wallace at Judge Owen's—A Pouting Lover and a Satisfied Rival—The Philosophy of Male and Female Jealousy—Frank Wallace doing the Insulting—A Bit of a Row—A Smash-up in the Streets, and a True Test of Relative Courage

The First Week of July—News of the Reverses before Richmond—Painful Feeling of the Whole Country—How a Nation weeps Tears of Blood—The Estimation of McClellan—The Curse of Absenteeism—Public Abhorrence of the Shoulder-strapped Heroes on Broadway—A Scene at the World Corner, and a Hero in Disguise

Leslie and Harding following up the Prince-Street Mystery—A Call upon Superintendent Kennedy—How Tom Leslie wished to play Detective—A Bit of a Rebuff—A Massachusetts Regiment going to the War—Miss Joe Harris and Bell Crawford in a Street Difficulty—A Rescue and a Recognition—A Trip into Taylor's Saloon

The True Characters of Men and of Houses—Fifth Avenue and the Swamp—Gilded Vice, and Vice without Ornament—The Progress of Temptation—The Legends of the Lurline and the Frozen Hand—Dangers of Fashionable Restaurants—Scenes at Taylor's Saloon—Tom Leslie, Joe Harris and Bell Crawford at Lunch—The Fortune-teller selected by Miss Harris for a Visit—Wanted, a Knight for Two Distressed Damsels—Tom Leslie enlists, and goes after his Armor

A Glance at Fortune-telling and other Delusions—Our Domestic and Personal Superstitions—Omens and their Origin—The Witch of Endor, Hamlet and Macbeth—One Strange Illustration of Prophecy in Dreams—The Fortune-tellers of New York, Boston and Washington

Ten Minutes at a Costumer's—Among the Robes of Queens and the Rags of Beggars—How Tom Leslie suddenly grew to Sixty, and changed Clothes accordingly—Josephine Harris and Bell Crawford still at Lunch, with a Dissertation upon One Pair of Eyes—An Unwarrantable Intrusion, and a Decided Sensation at Taylor's

Necromancy in a Thunder-storm—How Tom Leslie and his Female Companions called upon Madame Elise Boutell, from Paris, in Prince Street—A New Way of Gambling for Precedence—Bell Crawford takes her Turn—A very improper Joining of Hands in the Outer Apartment—About Chances, Accidents and Little Things—The Change in Bell Crawford's Eyes—Eyes that have looked within—Two Pictures in the Old Dusseldorf Gallery—Joe Harris Undergoing the Ordeal—A Thunder-clap and a Shriek of Terror—What Tom Leslie saw in the Apartment of the Red Woman—A Mask removed, and one more Temptation

Camp Lyon, and Colonel Egbert Crawford's Two Hundredth Regiment—Recruiting Discipline in the Summer of 1862—What Smith and Brown saw—Lager-beer, Cards and the Dice-box—An Adjutant who obeys Orders—A Dress Parade a la mode—How Seven Hundred Men may be squeezed into Three

A Few Words on the Two Modern Modes of writing Romances—How to tell what is not known and can never be known—The Bound of a Loyal Pen—More of the Up-town Mystery—How the Reliable Detectives posted a Watch, and how they kept it—Cold Water dampening Enthusiasm—An Escape, and the Post mortem hold on a Vacant House—Trails left by the Secession Serpent

Pictures at the Seat of War—Looking for John Crawford the Zouave—Hopeful and Discouraged Letters Home—Events which had preceded Malvern Hill—An Army winning Victories in Retreat—The Morning after White-Oak Swamp—How the Sun shines on Fields of Carnage—Appearance of the Retreating Army—The Camp of Fitz-John Porter's Division—The Soldiers of Home, and the Soldiers of the Field—The First Rebel Attack at the Cross Roads—Why the Potomac Army was not demoralized—The Repulse, and the Pause before the Heavier Storm

More of the First Battle of Malvern—A Word about Skulkers—An Attempt to flank the Union Forces—A Storm of Lead and Iron rivalling the War of the Elements—The Rebels Repulsed—The Attack on the Main Position, and the Second Battle of Malvern—The most Terrible Artillery Duel of the Century—Patriotism against Gunpowdered Whiskey—Shells from the Gun-boats, and their Effect—The Dead upon Carter's Field—The Last Repulse of the Rebels, and the General Advance of the Union Forces—Strange Incidents of the Close of the Battle—Odd Bravery in Meagher's Brigade—The Apparition in White, and its Effect—Close of the Great Battle

John Crawford the Zouave, and Bob Webster—Incidents of the Charge of Duryea's Zouaves—Bush-fighting and its Result—A Wound not bargained for—The Burning House and its Two Watchers—A Strange Death-scene—Marion Hobart and her Dying Grandfather—Death under the Old Flag—An Oath of Protection—A Furlough—John Crawford brings his Newly-acquired Family to New York

Judge Owen's Condemnation of the Rioters at his House—How Frank Wallace was exiled, and what came of it—The Burly Judge making a Household Arrest at Wallack's—Emily Owen and Joe Harris—A Recognition which may cause Further Trouble

Another Scene at Richard Crawford's—Josephine Harris playing the Detective, with Musical Accompaniments—A Sudden Demand for Dark Paste, with Difficulty in supplying it—A Young Girl who wished to be believed a Coward—Ever of Thee, with some Feelings thereunto attached—Josephine Harris pays a Visit to Doctor LaTurque—Her Discoveries with reference to the Obi Poison

A Little Arrangement between Tom Leslie and Joe Harris—Going to West Falls and Niagara—A Detention and a Night Scene on the Hudson-River Road—Why Joe Harris hid her Saucy Face—Oneida Scenery—Aunt Betsey, Little Susy, and a Peep at the Halstead Homestead, with Pigs, Chickens and Cherries

Josephine Harris in quest of Information—The Big House on the Hill—Extracting the Secrets of the Crawford Family—How a Big Fib may sometimes be told for a Good Purpose—Aunt Betsey made an Accomplice—Mary Crawford, the Country Girl, and a Terrible Revelation—A Bold Letter to a Bold Man

The Piazza of the Big House on the Hill—John Crawford the Human Wreck, and Egbert Crawford on the Eve of Marriage—Chanticleer on the Garden Fence, with Remembrances of Peter and Judas Iscariot—John Crawford instructs his Expectant Son-in-law—Arrival of the Domestic Post, with a Letter of Import—A Hit or a Miss?—Strida la Vampa

Affairs in the Crawford Family in New York—The Two Brothers together—Marion Hobart the Enigma—How Richard Crawford thought that he was not able to ride to the Central Park, and found that he could ride to Niagara

Tom Leslie at Niagara—A Dash at Scenery there—What he saw with his Natural Eyes, and what with his Inner Consciousness—The Wreck and the Rainbow—Another Rencontre with Dexter Ralston—The Eclipse on the Falls—Leslie under the impression that he can be discounted, and that he knows little or nothing on any subject

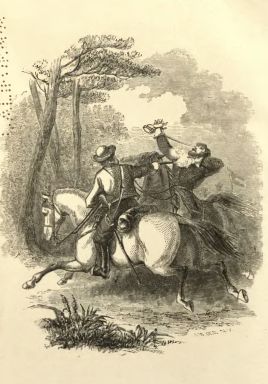

Society and Shoulder-Straps at the Falls—The Delights and Duties of a Journalist—Leslie and Harding Exploring Canada—How one Fine Morning War was declared between England and the United States, and Canada annexed to New York—A Meeting at the Cataract—Another Rencontre with the Strange Virginian—An Abduction and a Pursuit

The Sequel at West Falls—How Colonel Egbert Crawford was supposed to have been telegraphed for from Albany—Mary Crawford once more at the Halstead's—The Final Instructions and Promises of the Chief Conspirator—Joe Harris returns to the Great City, and her Disappointment therein—Another Conspiracy hatched, threatening to blow Judge Owen's Domestic Tranquillity to Atoms

Some Speculations on Moonlight and Insanity—Captain Robert Slivers, of the Sickles Brigade, makes his Appearance at Judge Owen's—He draws Graphic Pictures of the War, for the Edification of Colonel Bancker—A Controversy, with further inquiries as to the Age of the Colonel—The Market brisk for Hirsute Excrescences on the Cranium, and no Supply—Judge Owen laughs ponderously

Gathering the Ravelled Threads of a Long Story—What befel Several Persons heretofore named—Marriages in Demand, and only a few furnished—A Raid into Canada—What befell Colonel Egbert Crawford and the Two Hundredth Regiment—A Cavalry Charge at Antietam, and a Farewell

Two Friends—A Rencontre before Niblo's—Three Meetings with a Man of Mark—Mount Vernon and the Inauguration—Friend or Foe to the Union?

Just before the close of the performances at Niblo's Garden, where the Jarrett combination was then playing, one evening in the latter part of June, 1862, two young men came out from the doorway of the theatre and took their course up Broadway toward the Houston Street corner. Any observer who might have caught a clear view of the faces of the two as they passed under one of the large lamps at the door, would have noted each as being worth a second glance, but would at the same time have observed that two persons more dissimilar in appearance and in indication of character, could scarcely have been selected out of all the varied thousands resident in the great city.

The one walking on the inside as they passed on, with the right hand of his companion laid on his left arm in that confidential manner so common with intimate friends who wish to walk together in the evening without being jostled apart by hurried chance passengers, was somewhat tall in figure, dark-haired, dark side-whiskered, and sober-faced, though decidedly fine-looking; and in spite of the heat of the weather he preserved the appearance of winter dress clothing by a full suit of dark gray summer stuff that might well have been mistaken for broadcloth. Not even in hat or boots did he make any apparent concession to the season, for his glossy round hat would have been quite as much in place in January as in June, and his well-fitting and glossy patent-leather boots would have been thought oppressively warm by a hotter-blooded and more plethoric man. Those who should have seen the baptismal register recording his birth some five-and-thirty years before, would have known his name to be Walter Lane Harding; and those who met him in business or society would have become quite as well aware that he was a prosperous merchant, doing business in one of the leading mercantile streets running out of Broadway, not far from the City Hospital. So far as the somewhat precise mercantile appearance of Harding was concerned, a true disciple of Lavater would have judged correctly of him, for there were few men in the city of New York who displayed more steadiness, or greater money-making capacity in all the details of business; and yet even the close observer would have been likely to derive a false impression from this very preciseness, as to the social qualities of the man. There were quite as few better or heartier laughers than Harding, when duly aroused to mirth; and those persons were very rare, making the characters of mankind their professional study, who saw slight indications of disposition more quickly, or better enjoyed whatever gave food for quiet merriment. Once away from his counting-house, too, Walter Harding seemed to assume a second of his two natures that had before been lying dormant, and to enter into the permitted gaieties of city life with a zest that many a professed good fellow might have envied. He visited the theatre, as we have seen; went to the opera when it pleased him, not for fashion's sake, but because he liked music and was a connoisseur of singing and acting; liked a stroll in the streets with a congenial companion (male or female); could smoke a good cigar with evident enjoyment; and sometimes, though rarely, sipped a glass of fine old wine, and indulged in the freer pleasures of the table; though he was scrupulously careful of his company, and no man had ever seen his foot cross the threshold of a house of improper character. It is sufficient, in addition, at the present moment, to say that he was still a bachelor, occupying rooms in an up-town street, and enjoying life in that pleasant and rational mode which seemed to promise long continuance.

Harding's companion, who has already been indicated as his opposite, was markedly so in personal appearance, at least. He was two or three inches shorter than Harding, and much stouter, displaying a well-rounded leg through the folds of his loose pants of light-gray Melton cloth, and being quite well aware of that advantage of person. He had a smoothly rounded face, with a complexion that had been fair until hard work, late hours, and some exposure to the elements, had browned and roughened it; brown hair, with an evident tendency to curl, if he had not worn it so short on account of the heat of the season, that a curl was rendered impossible; a heavy dark brown moustache, worn without other beard; a sunny hazel eye that seemed made for laughter, and a full, red, voluptuous lip that might have belonged to a sensualist; while the eye could really do other things than laughing, and the lip was quite as often compressed or curled in the bitterness of disdain or the earnestness of close thought, as employed to express any warmer or more sympathetic feeling.

Tom Leslie, who might have been called by the more respectful and dignified name of "Thomas," but that no one had ever expended the additional amount of breath necessary to extend the name into two syllables, was a cadet of a leading family in a neighboring state, who at home had been reckoned the black sheep of the flock, because he would not settle quietly down like the rest to money-getting and the enjoyment of legislative offices; a man who at thirty had passed through much experience, seen a little dissipation, traveled over most States of the Union in the search for new scenery, or the fulfilment of his avocation as a newspaper correspondent and man of letters; been twice in Europe, alternately flying about like a madman, and sitting down to study life and manners in Paris, Vienna, and Rome, and gathering up all kinds of useful and useless information; taken a short turn at war in the Crimea, in 1853, as a private in the ranks of the French army; seen service for a few months in the Brazilian navy, from which he had brought a severe wound as a flattering testimonial. He was at that time located in New York as an editorial contributor and occasional "special correspondent" of a leading newspaper. He had seen much of life—tasted much of its pains and pleasures—perhaps thought more than either; and though with a little too much of a propensity for late hours and those long stories which would grow out of current events seen in the light of past experience, he was held to be a very pleasant companion by other men than Walter Harding.

Perhaps even the long stories were more a misfortune than a fault. The Ancient Mariner found it one of the saddest penalties of his crime, that he was obliged to button-hole all his friends and be written down an incorrigible bore; and who doubts that the Wandering Jew, with the weight of twenty centuries of experience and observation upon his head, finds a deeper pang than the tropic heat or the Arctic snow could give, in the want of an occasional quiet and patient listener to the story of his wanderings?

On the present occasion it may be noted, at once to complete the picture and give additional insight of a character which did very independent and outre things, that Tom Leslie had gone to Niblo's with his carefully-dressed and precise friend Harding, and sat conspicuously in an orchestra chair, in a gray business sack, no vest and no pretence at a collar. In other men, Harding would have noticed the dress with disapprobation: in Leslie it seemed to be legitimately a part of the man to dress as he liked; and neither Harding, or any one else who knew him, paid any more attention to his outward appearance than they would have bestowed upon a harmless lunatic under the same circumstances. Wherever Leslie boarded, (and his places of boarding were very numerous, taking the whole year together,) it was always noted that he filled up the hat-rack with a collection of hats of all odd and rapid styles, with a few of the more sedate and respectable; and on this evening's visit to Niblo's, when there was not a shadow of occasion for a hat with any brim whatever, he had completed his personal appearance by a fine gray beaver California soft hat, of not less than eighteen or twenty inches in the whole circumference, which gave him somewhat the appearance of being under a collapsed umbrella, and yet became him as well as any thing else could have done, and left him unmistakably a handsome fellow.

An oddly mixed compound, certainly—even odder than Harding; and yet what a dull, dead world this would prove to be, if there were no odd and outre characters to startle the grave people from their propriety, and throw an occasional pebble splashing into the pool of quiet and irreproachable mediocrity!

The two companions, whose description has occupied a much longer time than it needed to walk from the door of Niblo's to the Houston Street corner, were just passing the corner of that street on their way up to Bleecker, when they were momentarily stopped by a very ordinary incident. A girl, evidently of the demi-monde from her bold eyes, lavish display of charms and general demeanor, was turning the corner from Broadway into Houston Street immediately in front of Harding and Leslie; and as she swept around, her long dress trailing on the pavement, a careless fellow, lounging along, cigar in mouth, and eyes everywhere else than at his feet, stepped full upon her skirt, and before she could check the impetus of her sudden turn, literally tore the garment from her, the dark folds of the dress falling on the pavement and leaving the under-clothing painfully exposed. The girl turned suddenly, one of those harsh oaths upon her lips which even more than any action betray the fallen woman, and hissed out a malediction on his brutal carelessness. The man, probably one who literally knew no better, instead of remembering the provocation, apologizing for the injury he had done and offering to make any reparation in his power, replied by an oath still more shocking than that of the lost girl, hurled at her the most opprobrious epithet which man bestows upon woman in the English language, and one by far too obscene to be repeated in these pages,—and was passing on, leaving the poor girl to gather her torn drapery as she best could, when his course was suddenly arrested.

A tall figure had come up from below during the altercation, unnoticed by either; and the instant after the man had disgraced his humanity by that abuse of a fallen woman, he found himself seized by the collar with a hand that managed him as if he had been a child, and himself full off the sidewalk into the street, and among the wheels of the passing omnibuses, with the quick sharp words ringing in his ear:

"The devil take you! If you can't learn to walk along the pavement without tearing off women's dresses and afterwards abusing them, go out into the street with the brutes, where you belong!"

The two friends noticed, casually, that a policeman stood on the upper corner, and at this act of violence on the part of the new-comer, they naturally expected to see him interfere to preserve the peace, if not make an arrest; but he was either too lazy to cross the street, (such things have been,) or too well satisfied that the coarse ruffian had met the treatment he deserved, to make any step forward. The fellow, thus suddenly sent to the company of worn-out omnibus-horses and swearing stage-drivers on a slippery pavement, turned with an oath, when he recovered himself, made a movement as if to return to the sidewalk and seek satisfaction for the violence, but evidently did not like the looks of his antagonist, when he caught a fair glance of his proportions, and solaced himself with a few more muttered oaths as he dodged across to the other side of Broadway and disappeared in the crowd.

The second and prudential resolve of this person seemed fully justified by even a hasty survey of his assailant, who happened to be thrown under the light of the lamp at the corner, and in full view of our companions. He was perhaps six feet and an inch in height, cast in a most powerful model, and evidently possessing herculean strength—with a dark complexion, high cheek bones, showing almost as if he had a cross of the old Indian blood in his descent, fiery dark eyes set under brows of the pent-house or Webster mould, heavy massed black curly hair worn a little long, and a very heavy black moustache entirely concealing the mouth, while the beard shorn away from the lower portions of the face left the square, strong chin in full prominence. He was dressed in dark frock coat with white vest and pants, and wore a dark wide-brimmed slouched hat almost the counterpart of Leslie's, except in color, which harmonized well with his personal appearance in other regards, and while it left him looking the gentleman, made him the gentleman of some other locality than the city of New York.

The new-comer, the moment he had sent the other whirling into the street, approached the girl, who still remained standing on the corner, her ungathered dress sweeping the pavement, and said:

"Madame, your dress is badly torn. Allow me to offer you a few pins." He drew a large pin-cushion from his large vest pocket, (every thing seemed to be of a large pattern about this man,) and was handing it to the girl, who stretched out her left hand to receive it, when he suddenly seemed to recognize her.

"Why, Kate!" He spoke in tones of the most unfeigned surprise—"Kate, what the deuce! I thought you were in—"

"Yes, Deck!" answered the girl, with a coarse familiarity, "but you see I am here! And you? I thought you were in—"

"Hush-h-h!" said the man, in a quick, sharp, decided tone, prolonged almost to be a hiss. "That will do! Now use some of these pins—quick, fasten up your skirt, and then go with me!"

He spoke as if he was in the habit of being obeyed, or as if he had some peculiar claim that he should be obeyed in this instance. And the girl seemed fully to understand him, for only a moment served to supply so many pins to the torn gathers of the dress as enabled her to walk and hid her exposed under-clothing; and the instant that object was accomplished she thrust her arm into his, he making no attempt to repel the familiarity, but walking with hasty strides and almost dragging her after him, down into the partial gloom of Houston Street.

When they had disappeared, and not till then, the two friends removed from the spot where they had been standing entirely silent, and passed on up Broadway.

"A strange person—a very strange person, that!" said Harding, the moment after, to Leslie, who appeared to be thinking intently, and who had not uttered a word since the affair commenced.

"Y—a—es!" said Leslie, in that slow, abstracted tone which indicates that the man who uses it is doing so mechanically and without knowing what he says.

"Poor devil! how the new man whirled him out into the street!" Harding went on, his attention on the incident, as Leslie's apparently was not. "Just the treatment he deserved for being brutal to a woman, no matter how lost or degraded she may be! Tearing off her dress was all right enough, however, for all the woman deserve nothing better than to have their dresses torn into ribbons for thrusting them under our feet and sweeping the streets with them, as they do!"

Harding was thinking, at the moment, of a little adventure of his own a few weeks before, in which, hurrying along to an appointment, early in the evening, not far from the St. Nicholas, he had come up with a party of theatre-goers, trodden upon the dress of one of the ladies in attempting to pass—in extricating himself from that awkwardness, trodden upon the dresses of two more—and left the whole three nearly naked in the street; while three female voices were screaming in shame and mortification, and three male voices sending words after him the very reverse of complimentary.

"You think that a singular person?" at length said Leslie, as if waking from a reverie, but proving at the same time that he had heard the words of his friend. "You are right, he is so!"

"What! do you know him?" asked Harding, surprised.

"I do, indeed," was the reply of Leslie; "but I should as soon have thought of meeting Schamyl or Garibaldi in the streets of New York, at this moment, as the man we have just encountered. Fortunately, he did not recognize me—perhaps, thanks to this hat—(it is an immense hat, isn't it, Harding?) What can be his position, and what is his business here at the present moment, I wonder?" he went on, speaking more to himself than to his companion, as they turned down Bleecker from Broadway towards Leslie's lodgings, on Bleecker near Elm.

"Well, but you have not yet told me his name, or any thing about him, while you go on tantalizing me with speculations as to how he came to be here, and what he is doing!" said Harding.

"True enough," answered Leslie. "Well, he is not the sort of man to talk about loosely in the streets; so wait a moment, until I use my night-key and we get up into my room. There we can smoke a cigar, and I will tell you all I know of him, which is just enough to excite my wonder to a much greater height than your own."

Less than five minutes sufficed to fulfil the conditions prescribed; and in Leslie's little room, himself occupying the three chairs it contained, by sitting in one, and stretching out his two legs on the others, while Harding threw off his coat and lounged on the bed, Leslie poured out his story, and the smoke from his cigar, with about equal rapidity.

"The name of that singular man," he said, "is Dexter Balston, and he is by birth a Virginian. You heard the girl call him 'Deck,' which you no doubt took to be 'Dick,' but which she really meant as a familiar abbreviation of his name. It is a little singular that I should have met him first at a theatre, and not far from the one at which we just now encountered him. It was in the fall of 1857, I think, going in with a party of friends, one night, to Laura Keene's, that one of the ladies of the party was rudely jostled by a large man, who caught his foot in the matting of the vestibule and fell against her with such violence as nearly to throw her to the floor. He turned and apologized at once, and with so much high-toned and gentlemanly dignity, that all the party felt almost glad that the little accident had occurred. This made the first step of an acquaintance between him and myself; and when, in the intermission the same evening, I met him for a few moments in a saloon near the theatre, we drank together, held some slight conversation, exchanged cards, and each invited the other to call at his lodgings. His card lies somewhere in the bureau there at this moment, and it read, I remember, 'Dexter Ralston, Charles City, Virginia,' with 'St. Nicholas' written in pencil in the corner. He was a wealthy planter, living near Charles City, as I afterwards gathered from conversation with him, and had an interest in tobacco transactions at the North which kept him a large proportion of his time in this city.

"Of his own choice Ralston attended the theatres very frequently, as I did from professional duty; and the consequence was that we met often, and sometimes supped together. I liked him, and he seemed to be pleased with me, though I should be perverting the truth to say that I ever became very cordial or intimate with him. There was something about the man which forbade familiarity; though I remember thinking, several times, that if one only could penetrate beneath the crust made by that evident pride and haughty reserve, he was a man to be liked to the death by a man, and loved by a woman with eternal devotion. After a time, and without my receiving any 'P.P.C.' to say that he was going to leave the city, he disappeared, and I saw him no more in the street or at any of his favorite places of amusement.

"Well, I went down to Mount Vernon with a party of friends from Washington, on board the steamboat George Page. Did you ever know Page himself, the fat old Washingtonian who invented something about the circular-saw, and has some kind of a patent-right on all that are made above a certain number of inches in diameter? No? Well, he is an odd genius, and I will some day tell you something about him. But I was just now speaking of the steamboat named after him. The Rebels had her last year, you remember, using her as a gunboat somewhere up Aquia Creek, until they got scared and burned her one night,—though she was about as fit for that purpose as an Indian bark-canoe. The Page was running as an excursion boat to Mount Vernon, and sometimes going down to Aquia Creek in connection with the railroad, in the winter and spring of 1858-9. I was doing some reporting, and a little lobbying, in the Senate, at the beginning of March, and, as I have said, ran down with a party of friends to see the Tomb of Washington, curse the neglect that hung over it like a nightmare, and execrate the meanness which sold off bouquets from the garden, and canes from the woods, at a quarter each, by the hands of a pack of dirty slaves, to the hands of a pack of dirtier curiosity-hunters.

"Going down the river I found no acquaintances on board, outside of my own party; but when we had made the due inspection, and were returning in the afternoon, just when we were off Fort Washington, an acquaintance belonging to the capital came up, in conversation with a thin, scrawny, hard-featured man, dressed, in black, and looking like a cross between a decayed Yankee schoolmaster and a foreign Count gone into the hand-organ business. As we exchanged salutations he stopped, made a step backward, and astounded me by this introduction:

"'Col. Washington, my friend, Mr. Leslie—Mr. Leslie, Col. John A. Washington, proprietor of Mount Vernon.'

"I do not suppose that there was any merit in it, any more than there would have been in refusing to drink a nauseous dose; but, really, I felt that I was fulfilling a stern duty (no pun intended) in turning my back short upon the Colonel, and saying:

"'Much obliged to you, Mr. ——, but I have no desire whatever to know Col. John A. Washington!'

"I will do the Colonel (though he did afterwards die a rebel as he deserved) the justice to say that I do not think he cared much for the cut. I noticed that his sallow face looked a shade nearer to green than before, but he merely drew himself up and took no other notice of my decidedly cavalier conduct. Not so, however, with some of the passengers, who had been near enough to hear the words, and who seemed to think that the memory of the great dead was insulted, instead of honored, by this rebuff to the miserable offshoot who kept Mount Vernon as a cross between a pig-stye and a Jew old-clo' shop. Some of them, I suppose, were Virginians, and neighbors of 'the Colonel.' At all events, I heard mutterings, and the ladies in my company (they were all ladies) looked a little alarmed.

"Directly one of the F.F.V.'s, as I suppose them to have been, stepped forward immediately in front of me, and said:

"'D—n it, sir, the man who insults a Washington must answer to me!'

"'Must he?' I said, not much scared, I think, but a little flustered, and quite undecided whether to get into a row on the spot by striking the last man.

"'He must!' replied the F.F.V., with another curse or two thrown in by way of emphasis. 'You may be some cursed Yankee, peddling buttons, and afraid to fight; but if not—'

"'He will have no occasion to fight,' said a voice coming through the crowd from the side of the vessel. 'I will take that little job off his hands. Eh, Leslie, is that you? They tell me you have been giving the cut-direct to that mean humbug who calls himself John A. Washington. Give me your hand, old boy; you have done nothing more than your duty. I am a Virginian, and no d—d Yankee—does anybody want to fight me?'

"It was Dexter Ralston. How many of the people on board knew him I have no idea, or what they knew of him. He seemed to exercise some strange influence, however, for Col. Washington turned away, with the friend who had offered to introduce him; and the man who had offered to fight me also disappeared. The crowd at that spot on the deck seemed to be gone in a moment. Ralston and myself exchanged a few words. I thanked him for having extricated me from a possible scrape, as well as for his good opinion of my conduct, all which he waived with a 'pshaw!' He received an introduction to the ladies with all due courtesy, chatted with them a few moments, and then strolled off, smoking a cigar. I was engaged with my party for the remainder of the trip, and did not see him again until we had reached Washington and the passengers dispersed from the steamboat, when of course I lost him, without any inquiry being made as to his address or present residence. I went to Europe, the last time, as you know, the summer following, and so perhaps lost him more effectually. Tired?"

The latter word was especially addressed to Harding, who gave symptoms of going to sleep. Refreshed, however, by a cigar which Leslie thrust between his lips and insisted upon his smoking, Harding managed, even in his recumbent position, to keep awake for what followed.

"Confound you!" said Leslie, "you might manage to get along without yawning at my story, when you asked me to tell it! However, who cares! You are not the only man who does not know a good thing when he sees or hears it! Some of my best things in print have probably been received in like manner, by people just as stupid!"

"Very likely," said Harding, drily; and Leslie continued.

"I came home from Europe in the winter of 1860-61, as you may likewise remember if you are not too sleepy; and I was one of the ten thousand who went down from this city to Washington, to attend the inauguration of Abraham Lincoln. Nine thousand nine hundred and ninety odd went armed to the teeth, carrying each from one revolver to three, and a few bowie-knives, in anticipation of there being a general row on inauguration morning, if not an open attempt to assassinate the President. One man whom I could name actually carried four revolvers and a dirk, without knowing any more about the use of either than a child of ten years might have done. There was danger of a collision, of course, growing out of the very fact that everybody went down armed. I was one of the very few who could not borrow a revolver or did not want one—no matter which.

"Suffice it to say that I reached Washington on Sunday morning—the day previous to the inauguration—found the hotels full and took lodgings at a private house a few hundred yards from the Capitol, and spent the early part of the day in inspecting the preparations made for the holiday show, in and about the Capitol building. The courtesy of Colonel Forney, then Clerk of the House, arranged for my admission to the building during the ceremonies of the next day; and that of Douglas Wallach, of the Star, furnished me a seat in the reporters' gallery of the Senate for that evening when the last session of the expiring Congress was to be held and a last effort made for putting through those 'compromise resolutions' which it was then believed might 'save the Union,' but which we now know to have been as useless, even if they could have been passed, as so much whistling against the wind.

"Although it was Sunday, time was pressing, and the fate of the nation seemed to be hanging upon a breath; so the Senate had arranged a session for five o'clock, which seemed very likely to last well into the night, and was almost certain to be crowded to suffocation. As you will remember, it did last until seven the next morning—after daylight, and witnessed one of the most exciting debates in the history of that body,—in which Baker of Oregon flashed out even more than usual of his patriotic eloquence; and white-haired, sad old Crittenden of Kentucky moaned out words of fear for the nation, that have since been but too truly realized; and Mason of Virginia showed more boldly than ever the cloven foot of the traitor who would not have reconciliation at any price; and Douglas rose above his short stature in alternately lashing one and the other of those whom he believed to be equally enemies to his type of conservatism. No one who sat out that session will ever forget it—but enough of this, which should be written and not spoken.

"Of course after dinner that day I went down to the Hotels on the Avenue, to take a peep at the political barometer and see what was the prospect for violence on the morrow. It was a dark and stormy one. Most of the avowedly Southern element had disappeared from the street, and there were not many of the secession cockades to be met; but a few were flaunted by beardless young men who should that day have been arrested and thrown into the Old Capitol; and every foot of space in Willard's and the other leading houses was full all day long of a moving, surging, anxious and excited crowd, all talking, nobody listening, everybody inquiring, many significant hints, a few threats, an occasional quarrel and the interference of the police, but not much violence and no bloodshed. The evening shut down stormy, as to the national atmosphere, and I went home to supper impressed with the belief that the morrow could not pass off quietly—a belief strengthened by the fears of Scott; which were shown in the calling out of the volunteer militia in large force,—by the tap of the drum and the challenge of the sentry, which could be heard all around Capitol Hill,—and by the knowledge that files of regulars were barracked at different places on the Hill, ready for service in the morning and so posted as to command every avenue of ingress to the inauguration.

"One of the high winds which belong to the normal condition of Washington began blowing at dark, and it increased to a gale during the evening, rattling shutters, creaking signs and filling the air with clouds of blinding dust which went whirling around the Capitol as if they would bury it. This added materially to the appearance and feeling of desolation, especially when the white stone being worked for the Extension would gleam and disappear through the cloud, and suggest graveyards and monuments for the national greatness that seemed to be falling. Then at dusk we had the report that several hundreds of armed horsemen had been discovered by one of Scott's scouts, lying in wait over Anacosti, and ready to make a descent upon the doomed city the moment that it should be buried in slumber. Many doubted this report, but some believed it; and I have an impression that hundreds went to bed in Washington that night with a lingering doubt whether they would not be involved, before morning, or at all events before the noon of the next day, in such scenes of violence and bloodshed as the continent had never yet witnessed.

"I went over to the Capitol after tea, and took the place that had been kindly kept for me in the reporters' gallery of the Senate. No matter what occurred there—history has made it a part of our painful record, and that is quite sufficient. It was between one and two o'clock in the morning, Crittenden had just concluded his heart-breaking appeal to the North to be generous and not let the Union go by default, and Baker had just closed his noble appeal to the new dominant party (of which he was one) not to peril a nation by the adoption of the old Roman cry of 'Vae Victis,'—when I left the Senate gallery for an hour, intending to return when I had breathed for awhile outside of that suffocating atmosphere. I passed to the front through the entrance under the collonade, and was just about to step out into the open air, when a voice arrested me. Surely I had heard it before.

"'Straws against a whirlwind!' I heard it say. 'The work is already done, and no human power can undo it!'

"'I yet believe that the Union can be saved by the adoption of the plan proposed by Crittenden!' said the other voice. 'Mason is right when he says that Virginia will join the seceding States if no concession is made; but—'

"A laugh, deep, sonorous, and yet hollow and mocking, broke out from the lips of the first speaker, and rung through the arches—such a laugh as we may suppose to have rung from the bearded lips of the Norse Jarl when the poor Viking asked his daughter's hand and the father intended to stun if not to kill him with the bitter scoff. I had heard that laugh before, more moderately given, and minus the accompaniment of the rushing wind without and the ringing of the hollow arches within. It was that of Dexter Ralston, and I now detected that he and his companion were standing just within one of the embrasures, so as to be partially sheltered from the wind, and I could trace their outlines. Ralston was enveloped in a large cloak, and wearing his inevitable broad hat; and his companion seemed much smaller, dressed in dark clothes, and wearing the usual 'stovepipe.' I had no intention to play listener, but there really did not seem to be any wish for privacy on the part of the man who could laugh in that manner; and, at all events, I stood still in the doorway and listened to the discussion of that topic, as I might not have done to another.

"'Well, what does the laugh mean?' asked the other, in a tone that did not indicate remarkable good humor, when the sound had ceased.

"'Excuse me, I was not laughing at you!' said Ralston, 'but at the blind, besotted fools who believe that they hold in their hands the destinies of this Republic, and who really have no more power over them than so many children playing at marbles! Hear Crittenden and Baker begging and pleading within there, to save what is lost; and Mason, the sly old fox, threatening them with what is already done!'

"'What do you mean?' asked the other? 'Virginia—'

"'Virginia has seceded!' spoke Ralston, with an accent that sounded like a hiss. I do not to this moment know whether it expressed triumph or anger.

"'Seceded!' spoke the other, startled, as was evident from his voice. As for myself, I was trembling like a leaf, for I felt that the words were true, that the treason was already unfathomable, and that the Capitol was tumbling down about my ears long before it was finished.

"'Seceded? Yes, I spoke the word!' said Ralston, 'and you are not very likely to believe that I am mistaken.'

"'No, no, certainly not!' replied the other, in a tone of energetic disclaimer which showed that he knew why Ralston was not deceived. 'But then, if this is so, why does Mason remain, and why is the fact kept in the dark?'

"'To gain time!' answered Ralston, 'and to procure more arms. Virginia is a 'loyal State,' and arms may be shipped to her, while they cannot to the States that are known to have seceded. You can guess that the arms go further south almost as fast as they reach Richmond, and that Colt's pistols, especially, will pretty soon be beyond the reach of many men who live north of Mason and Dixon's line. Do you understand now?' he concluded.

"'Humph! Yes, I begin to know something more than I did a while ago!' answered the other. 'Then, as you say, all that is going on in yonder is a farce, and—'

"'And to-morrow's proceedings will be a more notable one!' Ralston broke in. 'Some of them, I believe, have been afraid of violence to-morrow. No fear of that—the game is to be played differently, and it is not yet ripe for blood. Well, I have had enough of it. Good-night!'

"At the word Ralston stepped out from the arch, and his companion followed him. By the lamp-light in front I caught a view of the face as the former went out, and saw that I had not been mistaken as to the voice. I had intended, when I first knew it was Ralston, to accost him before he left, but I had now lost the desire, while my head was in that whirl and his own position seemed to be so ambiguous. He stepped toward the gateway, and, I believe, entered a carriage and drove off. The other, whose face I recognized by the lamp-light to be that of a certain New York Congressman of more than doubtful antecedents, went back again the moment after, and I suppose returned to the Senate Chamber.

"As for myself, I may say that within half an hour after, late as it was, I had placed myself in communication with a leading member of the new party in power, with whom I happened to be well acquainted and who was well known to have the ear of the new President, even if he did not receive, within the next week, the portfolio of a Cabinet officer. I need not say, at present, whether he received the Cabinet appointment or not, as it is a matter of no consequence to my story. Without mentioning any names, I told him what had fallen under my notice, and gave him my opinion that Government ought to act as if Virginia had already seceded. He thanked me for the trouble I had taken, and for my earnestness; said that if the assertion was true, it would be highly important, as guiding the immediate policy of the administration; but, pshaw!—and the whole story is that he did not believe it. Of course the new administration did not act as if Virginia had seceded; the Rebels were allowed to gather arms at will and at leisure, Fortress Monroe came very near to falling into their hands, and Norfolk Navy Yard did so, with the destruction of half our best vessels, and ten millions of dollars worth of Government property—all which might have been avoided if they had taken a hint from a fool. Everybody understands now,[1] that Virginia had formally seceded before the inauguration, and that she played loyal for the very purposes indicated by Ralston.

[1] September, 1862.

"Now," Leslie concluded, "you know as much of Dexter Ralston as I do. And I think you will quite agree with me that he is one of the last men I could have expected to meet in the streets of New York at the present moment, when martial law is so prevalent and Fort Lafayette so convenient."

"Humph!" said Harding, getting up from the bed where he had lounged so long, examining his watch to see that it was nearly midnight, and lighting a fresh cigar to go home. "Humph! well, what do you make of him? A leading traitor, deep in the counsels of Jeff. Davis, Yancey and Company?"

"Humph!" said Leslie in return, "what else can he be?"

"Or a Virginia Unionist, faithful among the faithless, and too brave to be afraid anywhere?" suggested Harding.

"Ah!" answered Leslie, in that tone which suggests a new idea, or the corroboration of an old one.

"Or a trusted agent of the Federal Government, giving up old prejudices for the sake of patriotism, and better acquainted with Seward than Slidell—eh?"

"By George!" exclaimed Leslie, "there is something in that idea! He must be one of the three—but which?"

"That we may know better one of these days," said Harding, as Leslie accompanied him out to the street. "Meanwhile he is certainly a most singular person, and I shall not be sorry to know more of him, whether as friend or foe to the nation!"

How soon and how remarkably his wish was fulfilled, to some extent, we shall see hereafter.

The Invalid and the Wild Madonna—A Brave Heart Beating the Bars of its Prison—Odd Comfort and Doubtful Consolation—The Dawn of a Terrible Suspicion.

In the neat and tastefully-furnished back parlor of a house on West 3—th Street, one afternoon, at very nearly the same period mentioned in a previous chapter—the latter part of June, 1862—lay on the sofa a young man, of perhaps twenty-five, with a countenance that would have been strikingly handsome if it had not been drawn and attenuated by suffering. He had a well-chiselled face, clear blue eyes, and light-brown, curling hair, closely shaven of beard or moustache; still showing, spite of sickness, the manly nature that lay within, and which always makes, when it radiates outward, a pleasanter picture for the eye of a true woman than can be supplied by even high health and the most perfect physical beauty without it. The limbs, extended upon the sofa as he lay, though a little attenuated like the face, showed that they were well-formed and athletic. And the hand, drooping over the side of the couch, though too thinly white to suggest a love-pressure, indicated, in the taper of the fingers, and the fine round of the back, without any coarse protruding knuckles, what a handsome little Napoleonic hand it must have been when the owner was in full health and the life-blood coursing freely through his veins.

By the appearance of the little back parlor, it seemed to be half sick-room and half study, for, in addition to the sofa and an easy-chair, there was a well-filled book-case, in walnut, and a writing-desk open on a small table, with blank paper, some manuscripts, pens, ink, and a book or two lying open, as if the occupant had been writing not long before, and lain down from pain and weariness, without waiting to replace his writing materials in their proper position. Through the open door of a small room adjoining, some pieces of bed-room furniture could be seen, showing that when the invalid wished to find more complete repose, he could do so without painful removal to any distance. Close by his side lay a daily newspaper fallen upon the floor, with the sensation-headings of war-time displayed at the top of one of the columns; and in his hand he held a palm-leaf fan, with which he had apparently been trying to wave off some portion of the sultry heat of the afternoon. At length the fan grew still, the weak hand fell down on his breast, and he seemed to be dropping away into quiet slumber.

Suddenly a strain of martial music floated through the open windows—at first low and gentle, then bursting loud and clear, with the rattle of drums, the screaming of reeds and the clash of cymbals, as a band came nearer along the avenue and approached the corner of the street. The invalid's face lit up—he made a motion to rise hastily from the sofa—a sudden spasm of pain crossed his countenance, and he fell back exhausted, with a slight cry which instantly brought the sound of sliding doors between the little back parlor and the large room that adjoined it in front, and sent a pair of light feet flying into the room.

"Trying to get up again, eh, old fellow? I know you! Couldn't lie still when that music was going by! Now you great big boy, you ought to know better!" Such were the words with which the young girl greeted the sufferer, as she dropped down on her knees by the side of the sofa and took one of his hands in both hers.

"Yes, Joe, I was trying to get up and listen to the music," was the reply. "You know how I have always loved the brass band, and how it seems to rack my frame even worse than disease, just now! See what a wreck I am, when I cannot even attempt to rise from the sofa without screaming in that manner and alarming the house!"

"Oh, never mind alarming the house!" replied the girl, whom he had called "Joe," the very convenient and popular abbreviation of the Christian name of Miss Josephine Harris. She was, it may be said here, an almost every-day visitor from the house of her widowed mother, a lady in very comfortable circumstances, living not many blocks away up-town from the residence of the Crawfords. In ordinary seasons Joe and her mother (the young lady is made to precede the other, advisedly)—had a habit of getting away from the city, early in the season, to one of the watering-places or some cool retreat in the country; but this year perhaps the illness of Richard Crawford had something to do with retaining at least the daughter late in town. "The house can get along well enough—it is you that is to be taken care of, and I should like to know, Dick Crawford, how any body is going to do it if you do not manage to moderate your transports and lie still when you have not strength to do any thing else!"

How her tongue ran on, and what a tongue she had! Not a bit of sting in it, except when she was fully aroused to anger, and then it would suddenly develope the faculty of morally flaying her victim alive, with words of indignation that tumbled over each other without calculation or order, in the effort to escape the tears of vexation that were sure to follow close behind. At such moments Joe's tongue was actually cruel, though without premeditation; at other times it was simply a very rapid and noisy tongue, that spoke very sweet words most of the time and exercised an influence all around it that no one could attempt to describe. But perhaps the tongue was not alone concerned in the matter. There may have been something in the rather tall and lithe form—the brown cheek with a dash of color shining through it the moment she was in the least degree warmed or excited—the eyes dark but sunny, wavering between hazel brown and Irish gray, and the most difficult eyes in the world to look into and yet keep your head—the profile uneven and partially spoiled by the nose being decidedly pert, retroussé and too small for the other features—the pouting red lips that never seemed to fade and grow pale as the lips of so many American women do before one half their sweetness has been extracted by the human bee—the wealth of glossy black hair, coming down on the low forehead and plainly swept back in the Madonna fashion over a face that otherwise had the purity and goodness of the Madonna in it, but very little of her devotion,—perhaps there was something in all this, besides the influence of her flood-tide of language, to make Josephine Harris the delight, the botheration and the absolute tyrant of more than half the persons with whom she was thrown in contact. Perhaps there was even more than all, to those with whom she came into closer intercourse, in the breath that always seemed as if it came over a bank of over-ripe strawberries dying in the sun, late in summer—and that intoxicated with its aroma as rare old wine does with its flavor.

It is not difficult to believe (par parenthese) that the pearls and diamonds that dropped from the mouth of the good little princess in the old fairy story, every time she opened the ruby portals of her lips, dissolved themselves into air and came out in breath suggestive of spice-fields and orange-groves, and that the toads and scorpions falling from the mouth of her wicked sister manifested themselves in a corresponding rank and fetid odor. So bear with us, lady of the fevered breath, if we take the privilege of ago and long sight to drink in your flood of pleasant wisdom from a distance; and think not your lover overbold, Edie of the Red Lips, if he bends so near you when you speak, that the waves of brown and the curls of black even nestle together!

"Another sermon, eh, Joseph?" said the invalid, trying to smile and apparently soothed away from his pain by the very presence of the young girl. "Another sermon just because I cannot always remember that I am a poor miserable wreck!"

"Miserable fiddlestick!" said Joe, smoothing down his hair with both hands and accidentally stooping down so low that her lips came near enough to his forehead to breathe on it and send a pleasant creeping chill to the very tips of his toes. "I read you sermons, as you call them, because you are very impatient and very imprudent, and because I really have no one but yourself who is tied down so as not to be able to run away when I begin preaching. Don't you see that?"

"Yes, I do!" said the invalid, whom she had unconsciously introduced to us in calling him Dick Crawford—"I see!" and his face grew into a transient smile in spite of himself. "But where is my sister, and what was the music?"

"Two questions at once, like all the men!" the saucy girl answered. "But go ahead, for asking questions won't hurt your rheumatism. Bell has gone out shopping, I believe. She discovered an hour ago that there was a shade of cerise ribbon somewhere or other that she had not managed to get hold of, and of course she ordered the carriage at once and posted after it. As for the music—oh, the music was a brass band accompanying the One Hundred and Ninetieth Regiment. They are going to leave to-morrow, and they came up the avenue to receive a set of colors from Mrs. Pearl Dowlas, the ugly old woman with all that brown-stone incumbrance and three flags in the windows, round the corner."

"Going to-morrow!" said the invalid, and the old pained expression came back to his face. "Going to-morrow!—everybody is going!—and I lie here like a crushed worm, unable to move from my couch, useless to myself or to any one else, when the country is calling upon all her children to aid her! Pest on it! I would trade life, hopes, brains if I have any, every thing, for a sound body to-day!"

"And make a great fool of yourself in doing so!" was the flattering response of Josephine. "Now I suppose that music and my gabble have started the mill, and we shall have nothing else during the rest of the day than the same old weepings and wailings and gnashings of teeth. Just as if, because a war exists, there was nothing else in the world to do but to go to the war! Just as if we did not require some attention paid to the needs of the country at home, as well as on the battle-field! Just as if we did not need that the trade, and the literature—yes, the literature of the country—should be sustained."

"Pshaw!" said Crawford, impatiently, and making an effort to turn over, with his face to the wall.

"No you don't, old fellow!" cried the young girl, exercising the little restraint that was necessary. "You don't get away from me in that manner. I will stop your grumbling before I have done with you, by a remedy a little worse than the disease—plenty of my own gabble! I said literature—do you see that desk littered with papers, you ungrateful wretch?" (It will be seen that Josephine Harris had a habit of using strong Saxon words, as well as some that were "fast," not to say bordering upon popular slang; and the reader may as well be horrified with her, and get over it, first as last.) "You have sent out from that desk words that have done more good to the patriotic cause than the raising of ten regiments, and yet you have not the grace to thank God for giving you the strength to do that! You dare to lie there and call yourself useless! Out upon you—I am ashamed of you!"

"Words are not deeds!" said the young man, again moving uneasily.

"Words, when they come from the furnace of a true heart, shape themselves into deeds in others," was the reply.

"In the days of the Revolution, my ancestors did their deeds, instead of shaping them," said the invalid. "Two of them dead in the Old Sugar House and the prison ships at the Wallabout, and another crippled for life at Saratoga, bore witness that patriotism with them was no hollow pretence. And look at the present. My brother John going through battle after battle with Duryea's Zouaves, in Virginia, like a brave man and a soldier; and I lying helpless here, while my cousin Egbert has his regiment almost raised."

"Almost," said the young girl, in a tone which showed that she did not think he had quite accomplished that laudable endeavor.

"And will be going down directly," Crawford continued.

"Yes, going down, clear down, that is if he ever starts!" commented saucy Josephine.

"Yes, I remember, you do not like my cousin Egbert," said the invalid.

"I do not like humbugs anywhere!" sharply said the young girl. "Why don't you call him 'Eg.,' as you do sometimes? Then I should be tempted to make a few bad puns, and to say that in my opinion he is not a 'good egg,' but a 'hard egg,' if not a 'bad egg,' and that I hope if he ever gets among the Virginia sands he will come out a 'roast egg' or a 'cracked' one!"

"Shame, Joe, what do you mean!" said the invalid, really pained by her flippancy.

"Mean? why, mean what I say!" was the answer, "and that is a good deal more than most of the people do now-a-days. Your cousin Egbert is a big humbug! I never see him strutting about, with his shoulder-straps and his red sword-belts, but I have a mind to take the first off his shoulders, with claws like a cat, and use the second to strap him with, like a truant school-boy!"

"Why, Josephine, Josephine!" cried the invalid, still more surprised.

"Don't stop me!" said the wild girl. "I have intended for some time to say this to you, but you have been very sick, and somehow I could not begin the conversation. Now that it is begun, I am going to out with it, if it costs a lawsuit. I do not like that man, nor would you if you could know him half as well as I do. In the first place, I believe he is a coward, and worth no more to the cause than just what his gimcracks would sell for."

"Shame!" again said the invalid. "Josephine, you are really going too far. If he was a coward, why would he have placed himself in a position which must by-and-by be one of danger?

"Bah!" said the young girl, "I do not see that he has done any thing of the kind. Officers have the right of resigning, and some of them have the habit of skulking, I have heard. I will bet my best bonnet against your old worn-out slippers there, that if ever brought to the test your shoulder-strapped cousin would do one or the other! Besides—" and here she paused.

"Well, what is the 'besides'?" asked the young man, a little impatiently.

"Besides, he hates you like a rattlesnake, and would do any thing in his power to get you out of his way," the young girl said, giving out the words as if she was performing a painful operation and only doing it under a strong sense of duty. "Tell me: is there any point in which your interests would run counter to each other? I have seen daggers and poison in that man's eyes when looking at you, and when you have not observed him!"

"Interests?—in conflict? Good heavens, what are you saying, Josephine? Hate me—he?" and a terrible shadow passed over the face of the invalid. A moment before he had been unable to raise himself from the sofa, or bear the least motion, without agony. Now, in the excitement produced by her words and by some horrible doubt which they seemed to have awakened, he forgot the pain, or did not heed it, and struggled up to a sitting posture, his hands to his head and the whole expression of his face changed to one of intense mental suffering.

"Mr. Crawford—Dick!" the young girl cried in alarm; "what has happened—what have I said?—tell me: are you in sudden pain?" and she threw her arm around him to sustain him in his sitting position.

"Do not ask me!" he said, hoarsely. "I cannot speak just now, but you have agitated me very much. My cousin—in his way—heavens!"

At this moment, and when the young girl, frightened at what she had done, scarcely dared to speak another word, and was altogether at a loss what to do, there was a rattle of carriage wheels at the door, the sound of a latch-key applied to the lock, then steps and voices in the hall.

"Talk of the Prince of Darkness, and he is not very far from your elbow!" said Josephine, whose ears were sharper than those of the invalid. "I hear Bell's voice and that of the puissant and patriotic Colonel Egbert Crawford, who has evidently come home with her."

"His voice with hers, after what you have said!" the invalid gasped. "Lay me down quick, and hurt me as little as possible. I have not strength to sit up, and this pain—this pain—it drives me to distraction!" One hand was still at his head, and the other had fallen, whether accidentally or otherwise, over his heart. Whether the one hand or the other covered the pain of which he had that moment spoken, was difficult to tell. One thing was certain—that something in the last few moments had broken him down in health and spirits, even more than his long previous sickness. What was it?

Josephine, ever an excellent nurse in sickness (spite of her rapid tongue), and the one of all a crowd who was certain to have the head of the fainted woman on her breast, and her hands chafing the pallid temples,—assisted the invalid back to his recumbent position as quickly and as easily as possible; and at the moment when she had once more arranged the pillow under his head on the sofa, the glass doors between the front and back parlors slid gently apart, and Isabel Crawford and her cousin the Colonel, who had lately been the subject of so much speculation and agitation, approached the sofa of the rheumatic. His eyes were closed, and Josephine was standing at the open window with its closed blinds. Still she saw what the new-comers did not—a quick, convulsive shudder pass over the recumbent form, and the hand that lay on his heart close with a nervous spasm, as if it was crushing something hateful and dangerous that lay within it.

But the personal appearance of the two who had just entered, and the after events of that interview, must be recorded in a subsequent chapter.

Mother and Daughter—Love, Hate, and Disobedience—Judge Owen in a Storm—Aunt Martha and Her Record of Unloving Marriage and Wedded Outrage.

It was a very pleasant picture upon which Mrs. Maria Owen, wife of Judge Owen of the ——th District Court, was looking just at twilight of a June evening; but something in that picture, or its surroundings, did not seem to please her; for her comely though matronly face was drawn into an expression of displeasure, and the little mice about the wainscot, if any there were, might occasionally have heard her foot patting the floor with impatience and vexation.

The time has been already indicated. The place was the back parlor of Judge Owen's house, on a street not far from the Harlem River—the window open and the parlor opening into a neat little yard, half garden and half conservatory, with glimpses over the unoccupied lots beyond, of the junction of Harlem River with the Sound, up which the Boston boats had only a little while before disappeared on their way eastward, and where a few white sails of trading-schooners and pleasure-boats could yet be seen through the gathering twilight.

But this did not comprise all the picture upon which Mrs. Maria Owen looked; for in the window, with the last rays of the dying daylight falling upon face and figure, sat her daughter Emily, listlessly toying with the leaves of a book that she had been reading until the light grew too indistinct, and with a slight pout on her lip and an expression of dissatisfaction generally distributed over her pretty face, which showed that her own vexation and that of her mother had some kind of connection more or less mysterious. The face was not only pretty, as every one could see,—but softly rounded, womanly and most loveable while yet girlish, as only those could fully realize who had known something of the comparative characters of women. The eyes (in a better light) were hazel, with a depth and transparency which made the very thought of a mean action in her presence apparently impossible; the cheek that showed against the fading light had been rounded to perfection in the soft atmosphere floating about eighteen, as a peach is rounded and colored by the genial air and sunshine of late summer: the heavy masses of hair that had partially fallen out of their confinement and swept down to her shoulders, were scarcely darker than nut-brown; and the hand toying with the book would have shown, even without a better glimpse of the half recumbent figure, that that figure was of medium height, fully rounded and delicately voluptuous. It is not to be supposed that Emily Owen knew quite all this of herself. Some others realized all her perfections, however, as will more fully and at large appear (to use the conveyancers' phraseology); and for the purposes of this narrative it is necessary to have the lady distinctly before us.

And now what had caused the shadow on the matronly face of Mrs. Owen, and the pout on the red lip of Emily? The old—old story: told over at some period or other in almost every household on earth. Old eyes and young eyes, seeing very differently; old hearts and young hearts, beating to very different tunes, and informing the whole being with very different aspirations. There was a love—there was a dislike—and there was a certain amount of parental solicitude and determination—excellent materials from which to construct a serious disagreement and an eventual family row. Not Hecate, when she threw "eye of newt and tail of frog" into the infernal brew on the blasted heath, could have been more certain of the final nature of her compound, than may the presiding genius of any "well regulated family" be of the eventual result when the two acids of love and hate are brought chemically together in the heart of budding womanhood.

There was a certain John Boadley Bancker, a man of a family exceedingly respectable, though decayed, who had himself been a speculator in lands and stocks and amassed more or less money, and who was popularly understood to have been intrusted by Major General Governor Morgan with the authority of Colonel and the permission to raise a regiment for the war. There was a certain Frank Wallace, a young man of no particular family that any one had ever heard mentioned, a fellow of infinite jest and agreeableness, but very little money and no commission at all except to make love when necessary and extract as much comfort as possible from the passing hour,—who carried on a small printing business which just made him a comfortable livelihood, in a narrow street within a stone's throw of the Museum. It was the bounden duty of Miss Emily Owen, seeing that the portly Judge, her father, and the pleasant matron, her mother, had formed the very highest opinion of one of these gentlemen, to fall in love with him as quickly as possible. Of course she had contracted for him a most unconquerable aversion! It was her bounden duty to ignore the other, even if she did not hate and despise him—seeing that he found no other friend in her family: could there have been a stronger guaranty for her going madly in love with the scapegrace?

A moment after the period when we saw them sitting in silence and mutual discomfort, mother and daughter resumed the conversation which had brought about that state of feeling.

"You will be sorry for what you have said, Emily!" said the mother.

"So will you, for what you have said!" was the reply of the daughter, with that species of iteration which displays no wit but a great deal of earnestness.

"You know, as well as I do, that your father has set his heart upon this match," continued the mother, "and you know how much he is in the habit of allowing others to oppose him."

"Yes, I know," replied the young girl, "and I know one thing more."

"Indeed! and what is that?" asked the mother, with the slightest perceptible shade of a sneer in her voice.

"—That both you and my father made a serious blunder in bringing me into the world, if you meant to get along entirely without opposition!"

"Hoity toity!" exclaimed the mother, quite as much surprised as nettled at this original and forcible way of stating a domestic fact. "What has become of your modesty? Do you mean to insult both your father and myself?"

"No!" said the young girl, in a sharper tone and with her words cut off much shorter and more decidedly than was her habit. While those plump little white fingers had been toying with the leaves of the book, sitting there in the twilight, heart and hand had evidently both been busy, and they had produced any other effect rather than making their owner more tractable. "No! mother, no! But I tell you, once for all, that the match you are talking of is hateful! I have tried to keep still while the affair seemed at some distance, but now that you bring it closer it fills my whole being with disgust! Do drop it if you do not wish to drive me mad or make me disobedient. Oh, mother!" and the whole manner of the young girl seemed to change and melt in a moment, as she rose hastily from her chair, ran to that on which her mother was seated, threw herself on her knees with her arms around her parent, and buried her face in the sheltering lap,—"oh mother! do be my friend instead of my enemy, in this! I cannot—indeed I cannot marry that man!"

There are a good many things they think they cannot do—these young girls—and they never know themselves until they are tried. Perhaps it may not always be well to try them to their full capacity, however!

What Mrs. Maria Owen might have answered to this appeal, under other circumstances, is uncertain. She was, or intended to be, a good and tender mother, and would have cut off her right hand rather than do any thing which could make against the ultimate happiness of her daughter; and she really, at that moment, must have caught a glimpse of the fact that the heart of the young girl was very much interested in her refusal. But if there was any sentiment which the worthy woman entertained more deeply than another, it was the belief that Judge Owen, her husband, was the most wonderful man in the world. She thought of him with pride when his portly figure disappeared down the steps of a morning, when he was starting to go to "Court." She thought of him with a respect amounting to reverence when she contemplated him sitting

"At once mild and severe,

On his seat of dooming,"