THEY CAME TO THE PLACE WHERE HE HAD LEFT HER

Page 79

Project Gutenberg's Cossack Fairy Tales and Folk Tales, by Anonymous This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Cossack Fairy Tales and Folk Tales Author: Anonymous Illustrator: Noel L. Nisbet Translator: R. Nisbet Bain Release Date: August 12, 2009 [EBook #29672] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK COSSACK FAIRY TALES AND FOLK TALES *** Produced by David Edwards, Dan Horwood and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net. (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive.)

Uniform with this Volume

RUSSIAN FAIRY TALES

From the Skazki of Polevoi. By

R. Nisbet Bain. Illustrated in

Colour and Black and White by

Noel L. Nisbet

LONDON: GEORGE G. HARRAP & CO.

2 & 3 PORTSMOUTH STREET KINGSWAY W.C.

MCMXVI

PRINTED AT THE COMPLETE PRESS

WEST NORWOOD ENGLAND

| PAGE | |

| Introduction | 9 |

| Oh: The Tsar of the Forest | 15 |

| The Story of the Wind | 29 |

| The Voices at the Window | 49 |

| The Story of Little Tsar Novishny, the False Sister, and the Faithful Beasts | 57 |

| The Vampire and St Michael | 83 |

| The Story of Tremsin, the Bird Zhar, and Nastasia, the Lovely Maid of the Sea | 95 |

| The Serpent-Wife | 105 |

| The Story of Unlucky Daniel | 111 |

| The Sparrow and the Bush | 123 |

| The Old Dog | 129 |

| The Fox and the Cat | 133 |

| The Straw Ox | 139 |

| The Golden Slipper | 147 |

| The Iron Wolf | 159 |

| The Three Brothers | 167 |

| The Tsar and the Angel | 173 |

| The Story of Ivan and the Daughter of the Sun | 183 |

| The Cat, the Cock, and the Fox | 191 |

| The Serpent-Tsarevich and His Two Wives | 197 |

| The Origin of the Mole | 207 |

| The Two Princes | 211 |

| The Ungrateful Children and the Old Father Who Went to School Again | 219 |

| Ivan the Fool and St Peter’s Fife | 229 |

| The Magic Egg | 239 |

| The Story of the Forty-First Brother | 255 |

| The Story of the Unlucky Days | 261 |

| The Wondrous Story of Ivan Golik and the Serpents | 267 |

| PAGE | |

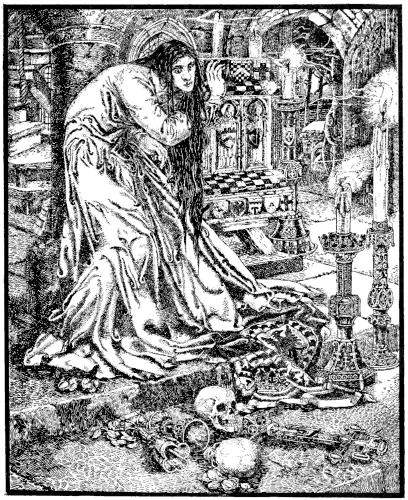

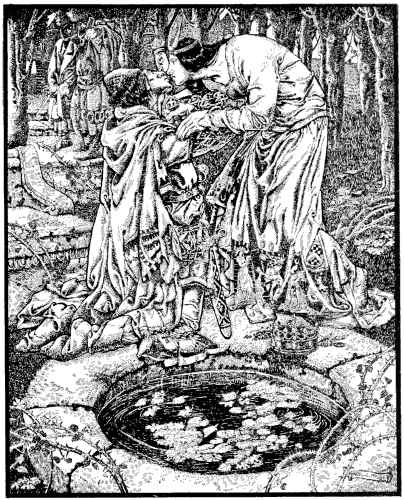

| They came to the place where he had left her | Frontispiece |

| All manner of evil powers walked abroad | 16 |

| “How much do you want for that horse?” | 24 |

| The wind came and swept all his corn away | 30 |

| “Out of the drum, my henchmen!” | 40 |

| The Tsarivna arose from her coffin | 86 |

| They were both on their knees | 90 |

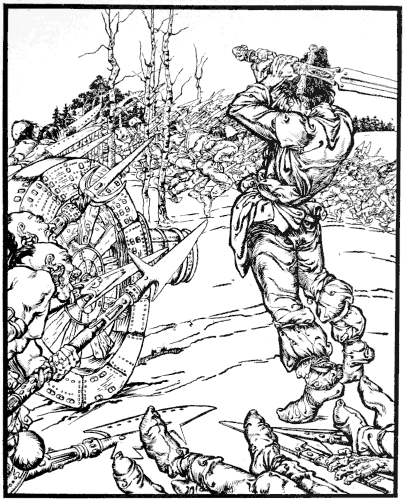

| Daniel waved his sword | 114 |

| His wife caressed and wheedled him | 118 |

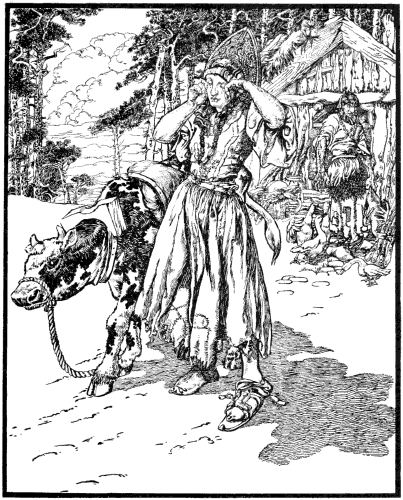

| The girl drove the heifer out to graze | 148 |

| The Tsar’s councillors went to the houses of all the nobles and princes | 154 |

| The Tsar went about inquiring of his people if any were wronged | 178 |

| The rulers of Hell laid hands upon the overseer straightway | 186 |

| Nineteen times did she cast off one of her suits of clothes | 198 |

| Suddenly St Peter appeared to him | 230 |

| Ivan Golik drew the bow | 276 |

The favourable reception given to my volume of Russian Fairy Tales has encouraged me to follow it up with a sister volume of stories selected from another Slavonic dialect extraordinarily rich in folk-tales––I mean Ruthenian, the language of the Cossacks.

Ruthenian is a language intermediate between Russian and Polish, but quite independent of both. Its territory embraces, roughly speaking, that vast plain which lies between the Carpathians, the watershed of the Dnieper, and the Sea of Azov, with Lemberg and Kiev for its chief intellectual centres. Though it has been rigorously repressed by the Russian Government, it is still spoken by more than twenty millions of people. It possesses a noble literature, numerous folk-songs, not inferior even to those of Serbia, and, what chiefly concerns us now, a copious collection of justly admired folk-tales, many of them of great antiquity, which are regarded, both in Russia and Poland, as quite unique of their kind. Mr Ralston, I fancy, was the first to call the attention of the West to these curious stories, though the want at that time of a good Ruthenian dictionary (a want since supplied by the excellent lexicon of Zhelekhovsky and Nidilsky) prevented him from utilizing them. Another Slavonic scholar, Mr Morfill, has also frequently alluded to them in terms of enthusiastic but by no means extravagant praise.

The three chief collections of Ruthenian folk-lore are those of Kulish, Rudchenko, and Dragomanov, 10 which represent, at least approximately, the three dialects into which Ruthenian is generally divided. It is from these three collections that the present selection has been made. Kulish, who has the merit of priority, was little more than a pioneer, his contribution merely consisting of some dozen kazki (Märchen) and kazochiki (Märchenlein), incorporated in the second volume of his Zapiski o yuzhnoi Rusi (“Descriptions of South Russia,” Petrograd, 1856-7). Twelve years later Rudchenko published at Kiev what is still, on the whole, the best collection of Ruthenian folk-tales, under the title of Narodnuiya Yuzhnorusskiya Skazki (“Popular South Russian Folk-tales”). Like Lïnnröt among the Finns, Rudchenko took down the greater part of these tales direct from the lips of the people. In a second volume, published in the following year, he added other stories gleaned from various minor manuscript collections of great rarity. In 1876 the Imperial Russian Geographical Society published at Kiev, under the title of Malorusskiya Narodnuiya Predonyia i Razkazui (“Little-Russian Popular Traditions and Tales”), an edition of as many manuscript collections of Ruthenian folk-lore (including poems, proverbs, riddles, and rites) as it could lay its hands upon. This collection, though far less rich in variants than Rudchenko’s, contained many original tales which had escaped him, and was ably edited by Michael Dragomanov, by whose name, indeed, it is generally known.

The present attempt to popularize these Cossack stories is, I believe, the first translation ever made from Ruthenian into English. The selection, though naturally restricted, is fairly representative; every variety 11 of folk-tale has a place in it, and it should never be forgotten that the Ruthenian kazka (Märchen), owing to favourable circumstances, has managed to preserve far more of the fresh spontaneity and naïve simplicity of the primitive folk-tale than her more sophisticated sister, the Russian skazka. It is maintained, moreover, by Slavonic scholars that there are peculiar and original elements in these stories not to be found in the folk-lore of other European peoples; such data, for instance, as the magic handkerchiefs (generally beneficial, but sometimes, as in the story of Ivan Golik, terribly baleful), the demon-expelling hemp-and-tar whips, and the magic cattle-teeming egg, so mischievous a possession to the unwary. It may be so, but, after all that Mr Andrew Lang has taught us on the subject, it would be rash for any mere philologist to assert positively that there can be anything really new in folk-lore under the sun. On the other hand, the comparative isolation and primitiveness of the Cossacks, and their remoteness from the great theatres of historical events, would seem to be favourable conditions both for the safe preservation of old myths and the easy development of new ones. It is for professional students of folk-lore to study the original documents for themselves.

R. N. B.

The olden times were not like the times we live in. In the olden times all manner of Evil Powers[1] walked abroad. The world itself was not then as it is now: now there are no such Evil Powers among us. I’ll tell you a kazka[2] of Oh, the Tsar of the Forest, that you may know what manner of being he was.

ALL MANNER OF EVIL POWERS WALKED ABROAD

Once upon a time, long long ago, beyond the times that we can call to mind, ere yet our great-grandfathers or their grandfathers had been born into the world, there lived a poor man and his wife, and they had one only son, who was not as an only son ought to be to his old father and mother. So idle and lazy was that only son that Heaven help him! He would do nothing, he would not even fetch water from the well, but lay on the stove all day long and rolled among the warm cinders. If they gave him anything to eat, he ate it; and if they didn’t give him anything to eat, he did without. His father and mother fretted sorely because of him, and said, “What are we to do with thee, O son? for thou art good for nothing. Other people’s children are a stay and a support to their parents, but thou art but a fool and dost consume our bread for naught.” But it was of no use at all. He would do nothing but sit on the stove and play with the cinders. So his father and mother grieved over him for many a long day, and at last his mother said to his father, “What is to be done with our son? Thou dost see that he has grown up and 16 yet is of no use to us, and he is so foolish that we can do nothing with him. Look now, if we can send him away, let us send him away; if we can hire him out, let us hire him out; perchance other folk may be able to do more with him than we can.” So his father and mother laid their heads together, and sent him to a tailor’s to learn tailoring. There he remained three days, but then he ran away home, climbed up on the stove, and again began playing with the cinders. His father then gave him a sound drubbing and sent him to a cobbler’s to learn cobbling, but again he ran away home. His father gave him another drubbing and sent him to a blacksmith to learn smith’s work. But there too he did not remain long, but ran away home again, so what was that poor father to do? “I’ll tell thee what I’ll do with thee, thou son of a dog!” said he. “I’ll take thee, thou lazy lout, into another kingdom. There, perchance, they will be able to teach thee better than they can here, and it will be too far for thee to run home.” So he took him and set out on his journey.

They went on and on, they went a short way and they went a long way, and at last they came to a forest so dark that they could see neither earth nor sky. They went through this forest, but in a short time they grew very tired, and when they came to a path leading to a clearing full of large tree-stumps, the father said, “I am so tired out that I will rest here a little,” and with that he sat down on a tree-stump and cried, “Oh, how tired I am!” He had no sooner said these words than out of the tree-stump, nobody could say how, sprang such a little, little old man, all so wrinkled and puckered, and his beard was quite green and reached right down to 17 his knee.––“What dost thou want of me, O man?” he asked.––The man was amazed at the strangeness of his coming to light, and said to him, “I did not call thee; begone!”––“How canst thou say that when thou didst call me?” asked the little old man.––“Who art thou, then?” asked the father.––“I am Oh, the Tsar of the Woods,” replied the old man; “why didst thou call me, I say?”––“Away with thee, I did not call thee,” said the man.––“What! thou didst not call me when thou saidst ‘Oh’?”––“I was tired, and therefore I said ‘Oh’!” replied the man.––“Whither art thou going?” asked Oh.––“The wide world lies before me,” sighed the man. “I am taking this sorry blockhead of mine to hire him out to somebody or other. Perchance other people may be able to knock more sense into him than we can at home; but send him whither we will, he always comes running home again!”––“Hire him out to me. I’ll warrant I’ll teach him,” said Oh. “Yet I’ll only take him on one condition. Thou shalt come back for him when a year has run, and if thou dost know him again, thou mayst take him; but if thou dost not know him again, he shall serve another year with me.”––“Good!” cried the man. So they shook hands upon it, had a good drink to clinch the bargain, and the man went back to his own home, while Oh took the son away with him.

Oh took the son away with him, and they passed into the other world, the world beneath the earth, and came to a green hut woven out of rushes, and in this hut everything was green; the walls were green and the benches were green, and Oh’s wife was green and his children were green––in fact, everything there was 18 green. And Oh had water-nixies for serving-maids, and they were all as green as rue. “Sit down now!” said Oh to his new labourer, “and have a bit of something to eat.” The nixies then brought him some food, and that also was green, and he ate of it. “And now,” said Oh, “take my labourer into the courtyard that he may chop wood and draw water.” So they took him into the courtyard, but instead of chopping any wood he lay down and went to sleep. Oh came out to see how he was getting on, and there he lay a-snoring. Then Oh seized him, and bade them bring wood and tie his labourer fast to the wood, and set the wood on fire till the labourer was burnt to ashes. Then Oh took the ashes and scattered them to the four winds, but a single piece of burnt coal fell from out of the ashes, and this coal he sprinkled with living water, whereupon the labourer immediately stood there alive again and somewhat handsomer and stronger than before. Oh again bade him chop wood, but again he went to sleep. Then Oh again tied him to the wood and burnt him and scattered the ashes to the four winds and sprinkled the remnant of the coal with living water, and instead of the loutish clown there stood there such a handsome and stalwart Cossack[3] that the like of him can neither be imagined nor described but only told of in tales.

There, then, the lad remained for a year, and at the end of the year the father came for his son. He came to the self-same charred stumps in the self-same forest, sat him down, and said, “Oh!” Oh immediately 19 came out of the charred stump and said, “Hail! O man!”––“Hail to thee, Oh!”––“And what dost thou want, O man?” asked Oh.––“I have come,” said he, “for my son.”––“Well, come then! If thou dost know him again, thou shalt take him away; but if thou dost not know him, he shall serve with me yet another year.” So the man went with Oh. They came to his hut, and Oh took whole handfuls of millet and scattered it about, and myriads of cocks came running up and pecked it. “Well, dost thou know thy son again?” said Oh. The man stared and stared. There was nothing but cocks, and one cock was just like another. He could not pick out his son. “Well,” said Oh, “as thou dost not know him, go home again; this year thy son must remain in my service.” So the man went home again.

The second year passed away, and the man again went to Oh. He came to the charred stumps and said, “Oh!” and Oh popped out of the tree-stump again. “Come!” said he, “and see if thou canst recognize him now.” Then he took him to a sheep-pen, and there were rows and rows of rams, and one ram was just like another. The man stared and stared, but he could not pick out his son. “Thou mayst as well go home then,” said Oh, “but thy son shall live with me yet another year.” So the man went away, sad at heart.

The third year also passed away, and the man came again to find Oh. He went on and on till there met him an old man all as white as milk, and the raiment of this old man was glistening white. “Hail to thee, O man!” said he.––“Hail to thee also, my father!”––“Whither doth God lead thee?”––“I am going to 20 free my son from Oh.”––“How so?”––Then the man told the old white father how he had hired out his son to Oh and under what conditions.––“Aye, aye!” said the old white father, “’tis a vile pagan thou hast to deal with; he will lead thee about by the nose for a long time.”––“Yes,” said the man, “I perceive that he is a vile pagan; but I know not what in the world to do with him. Canst thou not tell me then, dear father, how I may recover my son?”––“Yes, I can,” said the old man.––“Then prythee tell me, darling father, and I’ll pray for thee to God all my life, for though he has not been much of a son to me, he is still my own flesh and blood.”––“Hearken, then!” said the old man; “when thou dost go to Oh, he will let loose a multitude of doves before thee, but choose not one of these doves. The dove thou shalt choose must be the one that comes not out, but remains sitting beneath the pear-tree pruning its feathers; that will be thy son.” Then the man thanked the old white father and went on.

He came to the charred stumps. “Oh!” cried he, and out came Oh and led him to his sylvan realm. There Oh scattered about handfuls of wheat and called his doves, and there flew down such a multitude of them that there was no counting them, and one dove was just like another. “Dost thou recognize thy son?” asked Oh. “An thou knowest him again, he is thine; an thou knowest him not, he is mine.” Now all the doves there were pecking at the wheat, all but one that sat alone beneath the pear-tree, sticking out its breast and pruning its feathers. “That is my son,” said the man.––“Since thou hast guessed him, take him,” replied Oh. Then the father took the dove, and immediately it 21 changed into a handsome young man, and a handsomer was not to be found in the wide world. The father rejoiced greatly and embraced and kissed him. “Let us go home, my son!” said he. So they went.

As they went along the road together they fell a-talking, and his father asked him how he had fared at Oh’s. The son told him. Then the father told the son what he had suffered, and it was the son’s turn to listen. Furthermore the father said, “What shall we do now, my son? I am poor and thou art poor: hast thou served these three years and earned nothing?”––“Grieve not, dear dad, all will come right in the end. Look! there are some young nobles hunting after a fox. I will turn myself into a greyhound and catch the fox, then the young noblemen will want to buy me of thee, and thou must sell me to them for three hundred roubles––only, mind thou sell me without a chain; then we shall have lots of money at home, and will live happily together!”

They went on and on, and there, on the borders of a forest, some hounds were chasing a fox. They chased it and chased it, but the fox kept on escaping, and the hounds could not run it down. Then the son changed himself into a greyhound, and ran down the fox and killed it. The noblemen thereupon came galloping out of the forest. “Is that thy greyhound?”––“It is.”––“’Tis a good dog; wilt sell it to us?”––“Bid for it!”––“What dost thou require?”––“Three hundred roubles without a chain.”––“What do we want with thy chain, we would give him a chain of gold. Say a hundred roubles!”––“Nay!”––“Then take thy money and give us the dog.” They counted down the money and 22 took the dog and set off hunting. They sent the dog after another fox. Away he went after it and chased it right into the forest, but then he turned into a youth again and rejoined his father.

They went on and on, and his father said to him, “What use is this money to us after all? It is barely enough to begin housekeeping with and repair our hut.”––“Grieve not, dear dad, we shall get more still. Over yonder are some young noblemen hunting quails with falcons. I will change myself into a falcon, and thou must sell me to them; only sell me for three hundred roubles, and without a hood.”

They went into the plain, and there were some young noblemen casting their falcon at a quail. The falcon pursued but always fell short of the quail, and the quail always eluded the falcon. The son then changed himself into a falcon and immediately struck down its prey. The young noblemen saw it and were astonished. “Is that thy falcon?”––“’Tis mine.”––“Sell it to us, then!”––“Bid for it!”––“What dost thou want for it?”––“If ye give three hundred roubles, ye may take it, but it must be without the hood.”––“As if we want thy hood! We’ll make for it a hood worthy of a Tsar.” So they higgled and haggled, but at last they gave him the three hundred roubles. Then the young nobles sent the falcon after another quail, and it flew and flew till it beat down its prey; but then he became a youth again, and went on with his father.

“How shall we manage to live with so little?” said the father.––“Wait a while, dad, and we shall have still more,” said the son. “When we pass through the fair I’ll change myself into a horse, and thou must sell 23 me. They will give thee a thousand roubles for me, only sell me without a halter.” So when they got to the next little town, where they were holding a fair, the son changed himself into a horse, a horse as supple as a serpent, and so fiery that it was dangerous to approach him. The father led the horse along by the halter; it pranced about and struck sparks from the ground with its hoofs. Then the horse-dealers came together and began to bargain for it. “A thousand roubles down,” said he, “and you may have it, but without the halter.”––“What do we want with thy halter? We will make for it a silver-gilt halter. Come, we’ll give thee five hundred!”––“No!” said he. Then up there came a gipsy, blind of one eye. “O man! what dost thou want for that horse?” said he.––“A thousand roubles without the halter.”––“Nay! but that is dear, little father! Wilt thou not take five hundred with the halter?”––“No, not a bit of it!”––“Take six hundred, then!” Then the gipsy began higgling and haggling, but the man would not give way. “Come, sell it,” said he, “with the halter.”––“No, thou gipsy, I have a liking for that halter.”––“But, my good man, when didst thou ever see them sell a horse without a halter? How then can one lead him off?”––“Nevertheless, the halter must remain mine.”––“Look now, my father, I’ll give thee five roubles extra, only I must have the halter.”––The old man fell a-thinking. “A halter of this kind is worth but three grivni[4] and the gipsy offers me five roubles for it; let him have it.” So they clinched the bargain with a good drink, and the old man went home with the money, and the gipsy walked off 24 with the horse. But it was not really a gipsy, but Oh, who had taken the shape of a gipsy.

“HOW MUCH DO YOU WANT FOR THAT HORSE?”

Then Oh rode off on the horse, and the horse carried him higher than the trees of the forest, but lower than the clouds of the sky. At last they sank down among the woods and came to Oh’s hut, and Oh went into his hut and left his horse outside on the steppe. “This son of a dog shall not escape from my hands so quickly a second time,” said he to his wife. At dawn Oh took the horse by the bridle and led it away to the river to water it. But no sooner did the horse get to the river and bend down its head to drink than it turned into a perch and began swimming away. Oh, without more ado, turned himself into a pike and pursued the perch. But just as the pike was almost up with it, the perch gave a sudden twist and stuck out its spiky fins and turned its tail toward the pike, so that the pike could not lay hold of it. So when the pike came up to it, it said, “Perch! perch! turn thy head toward me, I want to have a chat with thee!”––“I can hear thee very well as I am, dear cousin, if thou art inclined to chat,” said the perch. So off they set again, and again the pike overtook the perch. “Perch! perch! turn thy head round toward me, I want to have a chat with thee!” Then the perch stuck out its bristly fins again and said, “If thou dost wish to have a chat, dear cousin, I can hear thee just as well as I am.” So the pike kept on pursuing the perch, but it was of no use. At last the perch swam ashore, and there was a Tsarivna[5] whittling an ash twig. The perch changed itself into a gold ring set with garnets, and the Tsarivna saw it and 25 fished up the ring out of the water. Full of joy she took it home, and said to her father, “Look, dear papa! what a nice ring I have found!” The Tsar kissed her, but the Tsarivna did not know which finger it would suit best, it was so lovely.

About the same time they told the Tsar that a certain merchant had come to the palace. It was Oh, who had changed himself into a merchant. The Tsar went out to him and said, “What dost thou want, old man?”––“I was sailing on the sea in my ship,” said Oh, “and carrying to the Tsar of my own land a precious garnet ring, and this ring I dropped into the water. Has any of thy servants perchance found this precious ring?”––“No, but my daughter has,” said the Tsar. So they called the damsel, and Oh began to beg her to give it back to him, “for I may not live in this world if I bring not the ring,” said he. But it was of no avail, she would not give it up.

Then the Tsar himself spoke to her. “Nay, but, darling daughter, give it up, lest misfortune befall this man because of us; give it up, I say!” Then Oh begged and prayed her yet more, and said, “Take what thou wilt of me, only give me back the ring.”––“Nay, then,” said the Tsarivna, “it shall be neither mine nor thine,” and with that she tossed the ring upon the ground, and it turned into a heap of millet-seed and scattered all about the floor. Then Oh, without more ado, changed into a cock, and began pecking up all the seed. He pecked and pecked till he had pecked it all up. Yet there was one single little grain of millet which rolled right beneath the feet of the Tsarivna, and that he did not see. When he had done 26 pecking he got upon the window-sill, opened his wings, and flew right away.

But the one remaining grain of millet-seed turned into a most beauteous youth, a youth so beauteous that when the Tsarivna beheld him she fell in love with him on the spot, and begged the Tsar and Tsaritsa right piteously to let her have him as her husband. “With no other shall I ever be happy,” said she; “my happiness is in him alone!” For a long time the Tsar wrinkled his brows at the thought of giving his daughter to a simple youth; but at last he gave them his blessing, and they crowned them with bridal wreaths, and all the world was bidden to the wedding-feast. And I too was there, and drank beer and mead, and what my mouth could not hold ran down over my beard, and my heart rejoiced within me.

Once upon a time there dwelt two brethren in one village, and one brother was very, very rich, and the other brother was very, very poor. The rich man had wealth of all sorts, but all that the poor man had was a heap of children.

One day, at harvest-time, the poor man left his wife and went to reap and thresh out his little plot of wheat, but the Wind came and swept all his corn away down to the very last grain. The poor man was exceeding wrath thereat, and said, “Come what will, I’ll go seek the Wind, and I’ll tell him with what pains and trouble I had got my corn to grow and ripen, and then he, forsooth! must needs come and blow it all away.”

THE WIND CAME AND SWEPT ALL HIS CORN AWAY

So the man went home and made ready to go, and as he was making ready his wife said to him, “Whither away, husband?”––“I am going to seek the Wind,” said he; “what dost thou say to that?”––“I should say, do no such thing,” replied his wife. “Thou knowest the saying, ‘If thou dost want to find the Wind, seek him on the open steppe. He can go ten different ways to thy one.’ Think of that, dear husband, and go not at all.”––“I mean to go,” replied the man, “though I never return home again.” Then he took leave of his wife and children, and went straight out into the wide world to seek the Wind on the open steppe.

He went on farther and farther till he saw before him a forest, and on the borders of that forest stood a hut on hens’ legs. The man went into this hut and was filled with astonishment, for there lay on the floor a 30 huge, huge old man, as grey as milk. He lay there stretched at full length, his head on the seat of honour,[6] with an arm and leg in each of the four corners, and all his hair standing on end. It was no other than the Wind himself. The man stared at this awful Ancient with terror, for never in his life had he seen anything like it. “God help thee, old father!” cried he.––“Good health to thee, good man!” said the ancient giant, as he lay on the floor of the hut. Then he asked him in the most friendly manner, “Whence hath God brought thee hither, good man?”––“I am wandering through the wide world in search of the Wind,” said the man. “If I find him, I will turn back; if I don’t find him, I shall go on and on till I do.”––“What dost thou want with the Wind?” asked the old giant lying on the floor. “Or what wrong hath he done thee, that thou shouldst seek him out so doggedly?”––“What wrong hath he done me?” replied the wayfarer. “Hearken now, O Ancient, and I will tell thee! I went straight from my wife into the field and reaped my little plot of corn; but when I began to thresh it out, the Wind came and caught and scattered every bit of it in a twinkling, so that there was not a single little grain of it left. So now thou dost see, old man, what I have to thank him for. Tell me, in God’s name, why such things be? My little plot of corn was my all-in-all, and in the sweat of my brow did I reap and thresh it; but the Wind came and blew it all away, so that not a trace of it is to be found in the wide world. Then I thought to myself, ‘Why should he do this?’ 31 And I said to my wife, ‘I’ll go seek the Wind, and say to him, “Another time, visit not the poor man who hath but a little corn, and blow it not away, for bitterly doth he rue it!”’”––“Good, my son!” said the giant who lay on the floor. “I shall know better in future; in future I will not blow away the poor man’s corn. But, good man, there is no need for thee to seek the Wind in the open steppe, for I myself am the Wind.”––“Then if thou art the Wind,” said the man, “give me back my corn.”––“Nay,” said the giant; “thou canst not make the dead come back from the grave. Yet, inasmuch as I have done thee a mischief, I will now give thee this sack, good man, and do thou take it home with thee. And whenever thou wantest a meal say, ‘Sack, sack, give me to eat and drink!’ and immediately thou shalt have thy fill both of meat and drink, so now thou wilt have wherewithal to comfort thy wife and children.”

Then the man was full of gratitude. “I thank thee, O Wind!” said he, “for thy courtesy in giving me such a sack as will give me my fill of meat and drink without the trouble of working for it.”––“For a lazy loon, ’twere a double boon,” said the Wind. “Go home, then, but look now, enter no tavern by the way; I shall know it if thou dost.”––“No,” said the man, “I will not.” And then he took leave of the Wind and went his way.

He had not gone very far when he passed by a tavern, and he felt a burning desire to find out whether the Wind had spoken the truth in the matter of the sack. “How can a man pass a tavern without going into it?” thought he; “I’ll go in, come what may. 32 The Wind won’t know, because he can’t see.” So he went into the tavern and hung up his sack upon a peg. The Jew who kept the tavern immediately said to him, “What dost thou want, good man?”––“What is that to thee, thou dog?” said the man.––“You are all alike,” sneered the Jew, “take what you can, and pay for nothing.”––“Dost think I want to buy anything from thee?” shrieked the man; then, turning angrily to the sack, he cried, “Sack, sack, give me to eat and drink!” Immediately the table was covered with all sorts of meats and liquors. Then all the Jews in the tavern crowded round full of amazement, and asked all manner of questions. “Why, what is this, good man?” said they; “never have we seen anything like this before!”––“Ask no questions, ye accursed Jews!” cried the man, “but sit down to eat, for there is enough for all.” So the Jews and the Jewesses set to and ate until they were full up to the ears; and they drank the man’s health in pitchers of wine of every sort, and said, “Drink, good man, and spare not, and when thou hast drunk thy fill thou shalt lodge with us this night. We’ll make ready a bed for thee. None shall vex thee. Come now, eat and drink whatever thy soul desires.” So the Jews flattered him with devilish cunning, and almost forced the wine-jars to his lips.

The simple fellow did not perceive their malice and cunning, and he got so drunk that he could not move from the place, but went to sleep where he was. Then the Jews changed his sack for another, which they hung up on a peg, and then they woke him. “Dost hear, fellow!” cried they; “get up, it is time to go home. Dost thou not see the morning light?” The man sat 33 up and scratched the back of his head, for he was loath to go. But what was he to do? So he shouldered the sack that was hanging on the peg, and went off home.

When he got to his house, he cried, “Open the door, wife!” Then his wife opened the door, and he went in and hung his sack on the peg and said, “Sit down at the table, dear wife, and you children sit down there too. Now, thank God! we shall have enough to eat and drink, and to spare.” The wife looked at her husband and smiled. She thought he was mad, but down she sat, and her children sat down all round her, and she waited to see what her husband would do next. Then the man said, “Sack, sack, give to us meat and drink!” But the sack was silent. Then he said again, “Sack, sack, give my children something to eat!” And still the sack was silent. Then the man fell into a violent rage. “Thou didst give me something at the tavern,” cried he; “and now I may call in vain. Thou givest nothing, and thou hearest nothing”––and, leaping from his seat, he took up a club and began beating the sack till he had knocked a hole in the wall, and beaten the sack to bits. Then he set off to seek the Wind again. But his wife stayed at home and put everything to rights again, railing and scolding at her husband as a madman.

But the man went to the Wind and said, “Hail to thee, O Wind!”––“Good health to thee, O man!” replied the Wind. Then the Wind asked, “Wherefore hast thou come hither, O man? Did I not give thee a sack? What more dost thou want?”––“A pretty sack indeed!” replied the man; “that sack of thine has been the cause of much mischief to me and mine.”––“What 34 mischief has it done thee?”––“Why, look now, old father, I’ll tell thee what it has done. It wouldn’t give me anything to eat and drink, so I began beating it, and beat the wall in. Now what shall I do to repair my crazy hut? Give me something, old father.”––But the Wind replied, “Nay, O man, thou must do without. Fools are neither sown nor reaped, but grow of their own accord––hast thou not been into a tavern?”––“I have not,” said the man.––“Thou hast not? Why wilt thou lie?”––“Well, and suppose I did lie?” said the man; “if thou suffer harm through thine own fault, hold thy tongue about it, that’s what I say. Yet it is all the fault of thy sack that this evil has come upon me. If it had only given me to eat and to drink, I should not have come to thee again.” At this the Wind scratched his head a bit, but then he said, “Well then, thou man! there’s a little ram for thee, and whenever thou dost want money say to it, ‘Little ram, little ram, scatter money!’ and it will scatter money as much as thou wilt. Only bear this in mind: go not into a tavern, for if thou dost, I shall know all about it; and if thou comest to me a third time, thou shalt have cause to remember it for ever.”––“Good,” said the man, “I won’t go.”––Then he took the little ram, thanked the Wind, and went on his way.

So the man went along leading the little ram by a string, and they came to a tavern, that very same tavern where he had been before, and again a strong desire came upon the man to go in. So he stood by the door and began thinking whether he should go in or not, and whether he had any need to find out the truth about the little ram. “Well, well,” said he at last, 35 “I’ll go in, only this time I won’t get drunk. I’ll drink just a glass or so, and then I’ll go home.” So into the tavern he went, dragging the little ram after him, for he was afraid to let it go.

Now, when the Jews who were inside there saw the little ram, they began shrieking and said, “What art thou thinking of, O man! that thou bringest that little ram into the room? Are there no barns outside where thou mayst put it up?”––“Hold your tongues, ye accursed wretches!” replied the man; “what has it got to do with you? It is not the sort of ram that fellows like you deal in. And if you don’t believe me, spread a cloth on the floor and you shall see something, I warrant you.”––Then he said, “Little ram, little ram, scatter money!” and the little ram scattered so much money that it seemed to grow, and the Jews screeched like demons.––“O man, man!” cried they, “such a ram as that we have never seen in all our days. Sell it to us! We will give thee such a lot of money for it.”––“You may pick up all that money, ye accursed ones,” cried the man, “but I don’t mean to sell my ram.”

Then the Jews picked up the money, but they laid before him a table covered with all the dishes that a man’s heart may desire, and they begged him to sit down and make merry, and said with true Jewish cunning, “Though thou mayst get a little lively, don’t get drunk, for thou knowest how drink plays the fool with a man’s wits.”––The man marvelled at the straightforwardness of the Jews in warning him against the drink, and, forgetting everything else, sat down at table and began drinking pot after pot of mead, and talking with the Jews, and his little ram went clean out of his 36 head. But the Jews made him drunk, and laid him in the bed, and changed rams with him; his they took away, and put in its place one of their own exactly like it.

When the man had slept off his carouse, he arose and went away, taking the ram with him, after bidding the Jews farewell. When he got to his hut he found his wife in the doorway, and the moment she saw him coming, she went into the hut and cried to her children, “Come, children! make haste, make haste! for daddy is coming, and brings a little ram along with him; get up, and look sharp about it! An evil year of waiting has been the lot of wretched me, but he has come home at last.”

The husband arrived at the door and said, “Open the door, little wife; open, I say!”––The wife replied, “Thou art not a great nobleman, so open the door thyself. Why dost thou get so drunk that thou dost not know how to open a door? It’s an evil time that I spend with thee. Here we are with all these little children, and yet thou dost go away and drink.”––Then the wife opened the door, and the husband walked into the hut and said, “Good health to thee, dear wife!”––But the wife cried, “Why dost thou bring that ram inside the hut, can’t it stay outside the walls?”––“Wife, wife!” said the man, “speak, but don’t screech. Now we shall have all manner of good things, and the children will have a fine time of it.”––“What!” said the wife, “what good can we get from that wretched ram? Where shall we get the money to find food for it? Why, we’ve nothing to eat ourselves, and thou dost saddle us with a ram besides. Stuff and nonsense! 37 I say.”––“Silence, wife,” replied the husband; “that ram is not like other rams, I tell thee.”––“What sort is it, then?” asked his wife.––“Don’t ask questions, but spread a cloth on the floor and keep thine eyes open.”––“Why spread a cloth?” asked the wife.––“Why?” shrieked the man in a rage; “do what I tell thee, and hold thy tongue.”––But the wife said, “Alas, alas! I have an evil time of it. Thou dost nothing at all but go away and drink, and then thou comest home and dost talk nonsense, and bringest sacks and rams with thee, and knockest down our little hut.”––At this the husband could control his rage no longer, but shrieked at the ram, “Little ram, little ram, scatter money!”––But the ram only stood there and stared at him. Then he cried again, “Little ram, little ram, scatter money!”––But the ram stood there stock-still and did nothing. Then the man in his anger caught up a piece of wood and struck the ram on the head, but the poor ram only uttered a feeble baa! and fell to the earth dead.

The man was now very much offended and said, “I’ll go to the Wind again, and I’ll tell him what a fool he has made of me.” Then he took up his hat and went, leaving everything behind him. And the poor wife put everything to rights, and reproached and railed at her husband.

So the man came to the Wind for the third time and said, “Wilt thou tell me, please, if thou art really the Wind or no?”––“What’s the matter with thee?” asked the Wind.––“I’ll tell thee what’s the matter,” said the man; “why hast thou laughed at and mocked me and made such a fool of me?”––“I laugh at thee!” 38 thundered the old father as he lay there on the floor and turned round on the other ear; “why didst thou not hold fast what I gave thee? Why didst thou not listen to me when I told thee not to go into the tavern, eh?”––“What tavern dost thou mean?” asked the man proudly; “as for the sack and the ram thou didst give me, they only did me a mischief; give me something else.”––“What’s the use of giving thee anything?” said the Wind; “thou wilt only take it to the tavern. Out of the drum, my twelve henchmen!” cried the Wind, “and just give this accursed drunkard a good lesson that he may keep his throat dry and listen a little more to old people!”––Immediately twelve henchmen leaped out of his drum and began giving the man a sound thrashing. Then the man saw that it was no joke and begged for mercy. “Dear old father Wind,” cried he, “be merciful, and let me get off alive. I’ll not come to thee again though I should have to wait till the Judgment Day, and I’ll do all thy behests.”––“Into the drum, my henchmen!” cried the Wind.––“And now, O man!” said the Wind, “thou mayst have this drum with the twelve henchmen, and go to those accursed Jews, and if they will not give thee back thy sack and thy ram, thou wilt know what to say.”

“OUT OF THE DRUM, MY HENCHMEN!”

So the man thanked the Wind for his good advice, and went on his way. He came to the inn, and when the Jews saw that he brought nothing with him they said, “Hearken, O man! don’t come here, for we have no brandy.”––“What do I want with your brandy?” cried the man in a rage.––“Then for what hast thou come hither?”––“I have come for my own.”––“Thy own,” 39 said the Jews; “what dost thou mean?”––“What do I mean?” roared the man; “why, my sack and my ram, which you must give up to me.”––“What ram? What sack?” said the Jews; “why, thou didst take them away from here thyself.”––“Yes, but you changed them,” said the man.––“What dost thou mean by changed?” whined the Jews; “we will go before the magistrate, and thou shalt hear from us about this.”––“You will have an evil time of it if you go before the magistrate,” said the man; “but at any rate, give me back my own.” And he sat down upon a bench. Then the Jews caught him by the shoulders to cast him out and cried, “Be off, thou rascal! Does any one know where this man comes from? No doubt he is an evil-doer.” The man could not stand this, so he cried, “Out of the drum, my henchmen! and give the accursed Jews a sound drubbing, that they may know better than to take in honest folk!” and immediately the twelve henchmen leaped out of the drum and began thwacking the Jews finely.––“Oh, oh!” roared the Jews; “oh, dear, darling, good man, we’ll give thee whatever thou dost want, only leave off beating us! Let us live a bit longer in the world, and we will give thee back everything.”––“Good!” said the man, “and another time you’ll know better than to deceive people.” Then he cried, “Into the drum, my henchmen!” and the henchmen disappeared, leaving the Jews more dead than alive. Then they gave the man his sack and his ram, and he went home, but it was a long, long time before the Jews forgot those henchmen.

So the man went home, and his wife and children saw him coming from afar. “Daddy is coming home 40 now with a sack and a ram!” said she; “what shall we do? We shall have a bad time of it, we shall have nothing left at all. God defend us poor wretches! Go and hide everything, children.” So the children hastened away, but the husband came to the door and said, “Open the door!”––“Open the door thyself,” replied the wife.––Again the husband bade her open the door, but she paid no heed to him. The man was astonished. This was carrying a joke too far, so he cried to his henchmen, “Henchmen, henchmen! out of the drum, and teach my wife to respect her husband!” Then the henchmen leaped out of the drum, laid the good wife by the heels, and began to give her a sound drubbing. “Oh, my dear, darling husband!” shrieked the wife, “never to the end of my days will I be sulky with thee again. I’ll do whatever thou tellest me, only leave off beating me.”––“Then I have taught thee sense, eh?” said the man.––“Oh, yes, yes, good husband!” cried she. Then the man said: “Henchmen, henchmen! into the drum!” and the henchmen leaped into it again, leaving the poor wife more dead than alive.

Then the husband said to her, “Wife, spread a cloth upon the floor.” The wife scudded about as nimbly as a fly, and spread a cloth out on the floor without a word. Then the husband said, “Little ram, little ram, scatter money!” And the little ram scattered money till there were piles and piles of it. “Pick it up, my children,” said the man, “and thou too, wife, take what thou wilt!”––And they didn’t wait to be asked twice. Then the man hung up his sack on a peg and said, “Sack, sack, meat and drink!” Then he caught 41 hold of it and shook it, and immediately the table was as full as it could hold with all manner of victuals and drink. “Sit down, my children, and thou too, dear wife, and eat thy fill. Thank God, we shall now have no lack of food, and shall not have to work for it either.”

So the man and his wife were very happy together, and were never tired of thanking the Wind. They had not had the sack and the ram very long when they grew very rich, and then the husband said to the wife, “I tell thee what, wife!”––“What?” said she.––“Let us invite my brother to come and see us.”––“Very good,” she replied; “invite him, but dost thou think he’ll come?”––“Why shouldn’t he?” asked her husband. “Now, thank God, we have everything we want. He wouldn’t come to us when we were poor and he was rich, because then he was ashamed to say that I was his brother, but now even he hasn’t got so much as we have.”

So they made ready, and the man went to invite his brother. The poor man came to his rich brother and said, “Hail to thee, brother; God help thee!”––Now the rich brother was threshing wheat on his threshing-floor, and, raising his head, was surprised to see his brother there, and said to him haughtily, “I thank thee. Hail to thee also! Sit down, my brother, and tell us why thou hast come hither.”––“Thanks, my brother, I do not want to sit down. I have come hither to invite thee to us, thee and thy wife.”––“Wherefore?” asked the rich brother.––The poor man said, “My wife prays thee, and I pray thee also, to come and dine with us of thy courtesy.”––“Good!” replied the rich brother, smiling secretly. “I will come whatever thy dinner may be.”

So the rich man went with his wife to the poor man, and already from afar they perceived that the poor man had grown rich. And the poor man rejoiced greatly when he saw his rich brother in his house. And his tongue was loosened, and he began to show him everything, whatsoever he possessed. The rich man was amazed that things were going so well with his brother, and asked him how he had managed to get on so. But the poor man answered, “Don’t ask me, brother. I have more to show thee yet.” Then he took him to his copper money, and said, “There are my oats, brother!” Then he took and showed him his silver money, and said, “That’s the sort of barley I thresh on my threshing-floor!” And, last of all, he took him to his gold money, and said, “There, my dear brother, is the best wheat I’ve got.”––Then the rich brother shook his head, not once nor twice, and marvelled at the sight of so many good things, and he said, “Wherever didst thou pick up all this, my brother?”––“Oh! I’ve more than that to show thee yet. Just be so good as to sit down on that chair, and I’ll show and tell thee everything.”

Then they sat them down, and the poor man hung up his sack upon a peg. “Sack, sack, meat and drink!” he cried, and immediately the table was covered with all manner of dishes. So they ate and ate, till they were full up to the ears. When they had eaten and drunken their fill, the poor man called to his son to bring the little ram into the hut. So the lad brought in the ram, and the rich brother wondered what they were going to do with it. Then the poor man said, “Little ram, scatter money!” And the little ram scattered money, till there were piles and piles of it on 43 the floor. “Pick it up!” said the poor man to the rich man and his wife. So they picked it up, and the rich brother and his wife marvelled, and the brother said, “Thou hast a very nice piece of goods there, brother. If I had only something like that I should lack nothing;” then, after thinking a long time, he said, “Sell it to me, my brother.”––“No,” said the poor man, “I will not sell it.”––After a little time, however, the rich brother said again, “Come now! I’ll give thee for it six yoke of oxen, and a plough, and a harrow, and a hay-fork, and I’ll give thee besides, lots of corn to sow, thus thou wilt have plenty, but give me the ram and the sack.” So at last they exchanged. The rich man took the sack and the ram, and the poor man took the oxen and went out to the plough.

Then the poor brother went out ploughing all day, but he neither watered his oxen nor gave them anything to eat. And next day the poor brother again went out to his oxen, but found them rolling on their sides on the ground. He began to pull and tug at them, but they didn’t get up. Then he began to beat them with a stick, but they uttered not a sound. The man was surprised to find them fit for nothing, and off he ran to his brother, not forgetting to take with him his drum with the henchmen.

When the poor brother came to the rich brother’s, he lost no time in crossing his threshold, and said, “Hail, my brother!”––“Good health to thee also!” replied the rich man, “why hast thou come hither? Has thy plough broken, or thy oxen failed thee? Perchance thou hast watered them with foul water, so that their blood is stagnant, and their flesh inflamed?”––“The 44 murrain take ’em if I know thy meaning!” cried the poor brother. “All that I know is that I thwacked ’em till my arms ached, and they wouldn’t stir, and not a single grunt did they give; till I was so angry that I spat at them, and came to tell thee. Give me back my sack and my ram, I say, and take back thy oxen, for they won’t listen to me!”––“What! take them back!” roared the rich brother. “Dost think I only made the exchange for a single day? No, I gave them to thee once and for all, and now thou wouldst rip the whole thing up like a goat at the fair. I have no doubt thou hast neither watered them nor fed them, and that is why they won’t stand up.”––“I didn’t know,” said the poor man, “that oxen needed water and food.”––“Didn’t know!” screeched the rich man, in a mighty rage, and taking the poor brother by the hand, he led him away from the hut. “Go away,” said he, “and never come back here again, or I’ll have thee hanged on a gallows!”––“Ah! what a big gentleman we are!” said the poor brother; “just thou give me back my own, and then I will go away.”––“Thou hadst better not stop here,” said the rich brother; “come, stir thy stumps, thou pagan! Go home ere I beat thee!”––“Don’t say that,” replied the poor man, “but give me back my ram and my sack, and then I will go.”––At this the rich brother quite lost his temper, and cried to his wife and children, “Why do you stand staring like that? Can’t you come and help me to pitch this insolent rogue out of the house?” This, however, was something beyond a joke, so the poor brother called to his henchmen, “Henchmen, henchmen! out of the drum, and give this brother of mine and his wife a sound drubbing, 45 that they may think twice about it another time before they pitch a poor brother out of their hut!” Then the henchmen leaped out of the drum, and laid hold of the rich brother and his wife, and trounced them soundly, until the rich brother yelled with all his might, “Oh, oh! my own true brother, take what thou wilt, only let me off alive!” whereupon the poor brother cried to his henchmen, “Henchmen, henchmen! into the drum!” and the henchmen disappeared immediately.

Then the poor brother took his ram and his sack, and set off home with them. And they lived happily ever after, and grew richer and richer. They sowed neither wheat nor barley, and yet they had lots and lots to eat. And I was there, and drank mead and beer. What my mouth couldn’t hold ran down my beard. For you, there’s a kazka, but there be fat hearth-cakes for me the asker. And if I have aught to eat, thou shalt share the treat.

A nobleman went hunting one autumn, and with him went a goodly train of huntsmen. All day long they hunted and hunted, and at the end of the day they had caught nothing. At last dark night overtook them. It had now grown bitterly cold, and the rain began to fall heavily. The nobleman was wet to the skin, and his teeth chattered. He rubbed his hands together and cried, “Oh, had we but a warm hut, and a white bed, and soft bread, and sour kvas,[7] we should have naught to complain of, but would tell tales and feign fables till dawn of day!” Immediately there shone a light in the depths of the forest. They hastened up to it, and lo! there was a hut. They entered, and on the table lay bread and a jug of kvas; and the hut was warm, and the bed therein was white––everything just as the nobleman had desired it. So they all entered after him, and said grace, and had supper, and laid them down to sleep.

They all slept, all but one, but to him slumber would not come. About midnight he heard a strange noise, and something came to the window and said, “Oh, thou son of a dog! thou didst say, ‘If we had but a warm hut, and a white bed, and soft bread, and sour kvas, we should have naught to complain of, but would tell tales and feign fables till dawn’; but now thou hast forgotten thy fine promise! Wherefore this shall befall thee on thy way home. Thou shalt fall in with an apple-tree full of apples, and thou shalt desire to taste of them, 50 and when thou hast tasted thereof thou shalt burst. And if any of these thy huntsmen hear this thing and tell thee of it, that man shall become stone to the knee!” All this that huntsman heard, and he thought, “Woe is me!”

And about the second cockcrow something else came to the window and said, “Oh, thou son of a dog! thou didst say, ‘If we had but a warm hut, and a white bed, and soft bread, and sour kvas, we should have naught to complain of, but would tell tales and feign fables till dawn’; but now thou hast forgotten thy fine promises! Wherefore this shall befall thee on thy way home. Thou shalt come upon a spring by the roadside, a spring of pure water, and thou shalt desire to drink of it, and when thou hast drunk thereof thou shalt burst. But if any of these thy huntsmen hear and tell thee of this thing, he shall become stone to the girdle.” All this that huntsman heard, and he thought to himself, “Woe is me!”

Again, toward the third cockcrow, he heard something else coming to the window, and it said, “Oh, thou son of a dog! thou didst say, ‘If only we had a warm hut, and a white bed, and soft bread, and sour kvas, we should have naught to complain of, but would tell tales and feign fables till dawn’; but now thou hast forgotten all thy fine promises! Wherefore this shall befall thee on thy way home. Thou shalt come upon a feather-bed in the highway; a longing for rest shall come over thee, and thou wilt lie down on it, and the moment thou liest down thereon thou shalt burst. But if any of thy huntsmen hear this thing and tell it thee, he shall become stone up to the neck!” All this 51 that huntsman heard, and then he awoke his comrades and said, “It is time to depart!”––“Let us go then,” said the nobleman.

So on they went, and they had not gone very far when they saw an apple-tree growing by the wayside, and on it were apples so beautiful that words cannot describe them. The nobleman felt that he must taste of these apples or die; but the wakeful huntsman rushed up and cut down the apple-tree, whereupon apples and apple-tree turned to ashes. But the huntsman galloped on before and hid himself.

They went on a little farther till they came to a spring, and the water of that spring was so pure and clear that words cannot describe it. Then the nobleman felt that he must drink of that water or die; but the huntsman rushed up and splashed in the spring with his sword, and immediately the water turned to blood. The nobleman was wrath, and cried, “Cut me down that son of a dog!” But the huntsman rode on in front and hid himself.

They went on still farther till they came upon a golden bed in the highway, full of white feathers so soft and cosy that words cannot describe it. The nobleman felt that he must rest in that bed or die. Then the huntsman rushed up and struck the bed with his sword, and it turned to coal. But the nobleman was very wrath, and cried, “Shoot me down that son of a dog!” But the huntsman rode on before and hid himself.

When they got home the nobleman commanded them to bring the huntsman before him. “What hast thou 52 done, thou son of Satan?” he cried. “I must needs slay thee!” But the huntsman said, “My master, bid them bring hither into the courtyard an old mare fit for naught but the knacker.” They brought the mare, and he mounted it and said, “My master, last midnight something came beneath the window and said, ‘Oh, son of a dog! thou saidst, “If only we had a warm hut, and a white bed, and soft bread, and sour kvas, we should grieve no more, but tell tales and feign fables till dawn,” and now thou hast forgotten thy promise. Wherefore this shall befall thee on thy way home: thou shalt come upon an apple-tree covered with apples by the wayside, and straightway thou shalt long to eat of them, and the moment thou tastest thereof thou shalt burst. And if any of thy huntsmen hears this thing, and tells thee of it, he shall become stone up to the knee.’” When the huntsman had spoken so far, the horse on which he sat became stone up to the knee. Then he went on, “About the second cockcrow something else came to the window and said the selfsame thing, and prophesied, ‘He shall come upon a spring by the roadside, a spring of pure water, and he shall long to drink thereof, and the moment he tastes of it he shall burst; and whoever hears and tells him of this thing shall become stone right up to the girdle.’” And when the huntsman had spoken so far, the horse on which he sat became stone right up to the breast. And he continued, and said, “About the third cockcrow something else came to the window and said the selfsame thing, and added, ‘This shall befall thy lord on his way home. He shall come upon a white bed on the road, and he shall desire to rest upon it, and 53 the moment he rests upon it he shall burst; and whoever hears and tells him of this thing shall become stone right up to the neck!’” And with these words he leaped from the horse, and the horse became stone right up to its neck. “That therefore, my master, was why I did what I did, and I pray thee pardon me.”

Once upon a time, in a certain kingdom, in a certain empire, there dwelt a certain Tsar who had never had a child. One day this Tsar went to the bazaar (such a bazaar as we have at Kherson) to buy food for his needs. For though he was a Tsar, he had a mean and churlish soul, and used always to do his own marketing, and so now, too, he bought a little salt fish and went home with it. On his way homeward, a great thirst suddenly fell upon him, so he turned aside into a lonely mountain where he knew, as his father had known before him, there was a spring of crystal-clear water. He was so very thirsty that he flung himself down headlong by this spring without first crossing himself, wherefore that Accursed One, Satan, immediately had power over him, and caught him by the beard. The Tsar sprang back in terror, and cried, “Let me go!” But the Accursed One held him all the tighter. “Nay, I will not let thee go!” cried he. Then the Tsar began to entreat him piteously. “Ask what thou wilt of me,” said he, “only let me go.”––“Give me, then,” said the Accursed One, “something that thou hast in the house, and then I’ll let thee go!”––“Let me see, what have I got?” said the Tsar. “Oh, I know. I’ve got eight horses at home, the like of which I have seen nowhere else, and I’ll immediately bid my equerry bring them to thee to this spring––take them.”––“I won’t have them!” cried the Accursed One, and he held him still more tightly by the beard. 58 “Well, then, hearken now!” cried the Tsar. “I have eight oxen. They have never yet gone a-ploughing for me, or done a day’s work. I’ll have them brought hither. I’ll feast my eyes on them once more, and then I’ll have them driven into thy steppes––take them.”––“No, that won’t do either!” said the Accursed One. The Tsar went over, one by one, all the most precious things he had at home, but the Accursed One said “No!” all along, and pulled him more and more tightly by the beard. When the Tsar saw that the Accursed One would take none of all these things, he said to him at last, “Look now! I have a wife so lovely that the like of her is not to be found in the whole world, take her and let me go!”––“No!” replied the Accursed One, “I will not have her.” The Tsar was in great straits. “What am I to do now?” thought he. “I have offered him my lovely wife, who is the very choicest of my chattels, and he won’t have her!”––Then said the Accursed One, “Promise me what thou shalt find awaiting thee at home, and I’ll let thee go.”

The Tsar gladly promised this, for he could think of naught else that he had, and then the Accursed One let him go.

But while he had been away from home, there had been born to him a Tsarevko[8] and a Tsarivna; and they grew up not by the day, or even by the hour, but by the minute: never were known such fine children. And his wife saw him coming from afar, and went out to meet him, with her two children, with great joy. But he, the moment he saw them, 59 burst into tears. “Nay, my dear love,” cried she, “wherefore dost thou burst into tears? Or art thou so delighted that such children have been born unto thee that thou canst not find thy voice for tears of joy?”––And he answered her, “My darling wife, on my way back from the bazaar I was athirst, and turned toward a mountain known of old to my father and me, and it seemed to me as though there were a spring of water there, though the water was very near dried up. But looking closer, I saw that it was quite full; so I bethought me that I would drink thereof, and I leaned over, when lo! that Evil-wanton (I mean the Devil) caught me by the beard and would not let me go. I begged and prayed, but still he held me tight. ‘Give me,’ said he, ‘what thou hast at home, or I’ll never let thee go!’––And I said to him, ‘Lo! now, I have horses.’––‘I don’t want thy horses!’ said he.––‘I have oxen,’ I said.––‘I don’t want thine oxen!’ said he.––‘I have,’ said I, ‘a wife so fair that the like of her is not to be found in God’s fair world; take her, but let me go.’––‘I don’t want thy fair wife!’ said he.––Then I promised him what I should find at home when I got there, for I never thought that God had blessed me so. Come now, my darling wife! and let us bury them both lest he take them!”––“Nay, nay! my dear husband, we had better hide them somewhere. Let us dig a ditch by our hut––just under the gables!” (For there were no lordly mansions in those days, and the Tsars dwelt in peasants’ huts.) So they dug a ditch right under the gables, and put their children inside it, and gave them provision of bread and water. Then they covered it up and 60 smoothed it down, and turned into their own little hut.

Presently the serpent (for the Accursed One had changed himself into a serpent) came flying up in search of the children. He raged up and down outside the hut––but there was nothing to be seen. At last he cried out to the stove, “Stove, stove, where has the Tsar hidden his children?”––The stove replied, “The Tsar has been a good master to me; he has put lots of warm fuel inside me; I hold to him.”––So, finding he could get nothing out of the stove, he cried to the hearth-broom, “Hearth-broom, hearth-broom, where has the Tsar hidden his children?”––But the hearth-broom answered, “The Tsar has always been a good master to me, for he always cleans the warm grate with me; I hold to him.” So the Accursed One could get nothing out of the hearth-broom.––Then he cried to the hatchet, “Hatchet, hatchet, where has the Tsar hidden his children?”––The hatchet replied, “The Tsar has always been a good master to me. He chops his wood with me, and gives me a place to lie down in; so I’ll not have him disturbed.”––Then the Devil cried to the gimlet, “Gimlet, gimlet, where has the Tsar hidden his children?”––But the gimlet replied, “The Tsar has always been a good master to me. He drills little holes with me, and then lets me rest; so I’ll let him rest too.”––Then the serpent said to the gimlet, “So the Tsar’s a good master to thee, eh! Well, I can only say that if he’s the good master thou sayest he is, I am rather surprised that he knocks thee on the head so much with a hammer.”––“Well, that’s true,” 61 said the gimlet, “I never thought of that. Thou mayst take hold of me if thou wilt, and draw me out of the top of the hut, near the front gable; and wherever I fall into the marshy ground, there set to work and dig with me!”

The Devil did so, and began digging at the spot where the gimlet fell out on the marshy ground till he had dug out the children. Now, as they had been growing all along, they were children no more, but a stately youth and a fair damsel; and the serpent took them up and carried them off. But they were big and heavy, so he soon got tired and lay down to rest, and presently fell asleep. Then the Tsarivna sat down on his head, and the Tsarevko sat down beside her, till a horse came running up. The horse ran right up to them and said, “Hail! little Tsar Novishny; art thou here by thy leave or against thy leave?”––And the little Tsar Novishny replied, “Nay, little nag! we are here against our leave, not by our leave.”––“Then sit on my back!” said the horse, “and I’ll carry you off!” So they got on his back, for the serpent was asleep all the time. Then the horse galloped off with them; and he galloped far, far away. Presently the serpent awoke, looked all round him, and could see nothing till he had got up out of the reeds in which he lay, when he saw them in the far distance, and gave chase. He soon caught them up; and little Tsar Novishny said to the horse, “Oh! little nag, how hot it is. It is all up with thee and us!” And, in truth, the horse’s tail was already singed to a coal, for the serpent was hard behind them, blazing like fire. The horse perceived that he could do no more, so he 62 gave one last wriggle and died; but they, poor things, were left alive. “Whom have you been listening to?” said the serpent as he flew up to them. “Don’t you know that I only am your father and tsar, and have the right to carry you away?”––“Oh, dear daddy! we’ll never listen to anybody else again!”––“Well, I’ll forgive you this time,” said the serpent; “but mind you never do it again.”

Again the serpent took them up and carried them off. Presently he grew tired and again lay down to rest, and nodded off. Then the Tsarivna sat down on his head, and the Tsarevko sat down beside her, till a humble-bee came flying up. “Hail, little Tsar Novishny!” cried the humble-bee.––“Hail, little humble-bee!” said the little Tsar.––“Say, friends, are you here by your leave or against your leave?”––“Alas! little humble-bumble-bee, ’tis not with my leave I have been brought hither, but against my leave, as thou mayst see for thyself.”––“Then sit on my back,” said the bee, “and I’ll carry you away.”––“But, dear little humble-bumble-bee, if a horse couldn’t save us, how will you?”––“I cannot tell till I try,” said the humble-bee. “But if I cannot save you, I’ll let you fall.”––“Well, then,” said the little Tsar, “we’ll try. For we two must perish in any case, but thou perhaps mayst get off scot-free.” So they embraced each other, sat on the humble-bee, and off they went. When the serpent awoke he missed them, and raising his head above the reeds and rushes, saw them flying far away, and set off after them at full speed. “Alas! little humble-bumble-bee,” cried little Tsar Novishny, “how burning hot ’tis getting. We shall all three 63 perish!” Then the humble-bee turned his wing and shook them off. They fell to the earth, and he flew away. Then the serpent came flying up and fell upon them with open jaws. “Ah-ha!” cried he, with a snort, “you’ve come to grief again, eh? Didn’t I tell you to listen to nobody but me!” Then they fell to weeping and entreating, “We’ll listen to you alone and to nobody else!” and they wept and entreated so much that at last he forgave them.

So he took them up and carried them off once more. Again he sat down to rest and fell asleep, and again the Tsarivna sat upon his head and the Tsarevko sat down by her side, till a bullock came up, full tilt, and said to them, “Hail, little Tsar Novishny! art thou here with thy leave or art thou here against thy leave?”––“Alas! dear little bullock, I came not hither by my leave; but maybe I was brought here against my leave!”––“Sit on my back, then,” said the bullock, “and I’ll carry you away.”––But they said, “Nay, if a horse and a bee could not manage it, how wilt thou?”––“Nonsense!” said the bullock. “Sit down, and I’ll carry you off!” So he persuaded them.––“Well, we can only perish once!” they cried; and the bullock carried them off. And every little while they went a little mile, and jolted so that they very nearly tumbled off. Presently the serpent awoke and was very very wrath. He rose high above the woods and flew after them––oh! how fast he did fly! Then cried the little Tsar, “Alas! bullock, how hot it turns. Thou wilt perish, and we shall perish also!”––Then said the bullock, “Little Tsar! look into my left ear and thou wilt see a horse-comb. Pull it out and throw it behind 64 thee!”––The little Tsar took out the comb and threw it behind him, and it became a huge wood, as thick and jagged as the teeth of a horse-comb. But the bullock went on at his old pace: every little while they went a little mile, and jolted so that they nearly tumbled off. The serpent, however, managed to gnaw his way through the wood, and then flew after them again. Then cried the little Tsar, “Alas! bullock, it begins to burn again. Thou wilt perish, and we shall perish also!”––Then said the bullock, “Look into my right ear, and pull out the brush thou dost find there, and fling it behind thee!”––So he threw it behind him, and it became a forest as thick as a brush. Then the serpent came up to the forest and began to gnaw at it; and at last he gnawed his way right through it. But the bullock went on at his old pace: every little while they went a little mile, and they jolted so that they nearly tumbled off. But when the serpent had gnawed his way through the forest, he again pursued them; and again they felt a burning. And the little Tsar said, “Alas! bullock, look! look! how it burns. Look! look! how we perish.” Now the bullock was already nearing the sea. “Look into my right ear,” said the bullock, “draw out the little handkerchief thou findest there, and throw it in front of me.” He drew it out and flung it, and before them stood a bridge. Over this bridge they galloped, and by the time they had done so, the serpent reached the sea. Then said the bullock to the little Tsar, “Take up the handkerchief again and wave it behind me.” Then he took and waved it till the bridge doubled up behind them, and went and spread out again right in front 65 of them. The serpent came up to the edge of the sea; but there he had to stop, for he had nothing to run upon.

So they crossed over that sea right to the other side, and the serpent remained on his own side. Then the bullock said to them, “I’ll lead you to a hut close to the sea, and in that hut you must live, and you must take and slay me.” But they fell a-weeping sore. “How shall we slay thee!” they cried; “thou art our own little dad, and hast saved us from death!”––“Nay!” said the bullock; “but you must slay me, and one quarter of me you must hang up on the stove, and the second quarter you must place on the ground in a corner, and the third quarter you must put in the corner at the entrance of the hut, and the fourth quarter you must put round the threshold, so that there will be a quarter in all four corners.” So they took and slew him in front of the threshold, and they hung his four quarters in the four corners as he had bidden them, and then they laid them down to sleep. Now the Tsarevko awoke at midnight, and saw in the right-hand corner a horse so gorgeously caparisoned that he could not resist rising at once and mounting it; and in the threshold corner there was a self-slicing sword, and in the third corner stood the dog Protius[9], and in the stove corner stood the dog Nedviga[9]. The little Tsar longed to be off. “Rise, little sister!” cried he. “God has been good to us! Rise, dear little sister, and let us pray to God!” So they arose and prayed to God, and while they prayed the day dawned. Then he mounted his horse and took the dogs with him, that he might live by what they caught.

So they lived in their hut by the sea, and one day the sister went down to the sea to wash her bed-linen and her body-linen in the blue waters. And the serpent came and said to her, “How didst thou manage to jump over the sea?”––“Look, now!” said she, “we crossed over in this way. My brother has a handkerchief which becomes a bridge when he waves it behind him.”––And the serpent said to her, “I tell thee what, ask him for this handkerchief; say thou dost want to wash it, and take and wave it, and I’ll then be able to cross over to thee and live with thee, and we’ll poison thy brother.”––Then she went home and said to her brother, “Give me that handkerchief, dear little brother; it is dirty, so I’ll wash and give it back to thee.” And he believed her and gave it to her, for she was dear to him, and he thought her good and true. Then she took the handkerchief, went down to the sea, and waved it––and behold there was a bridge. Then the serpent crossed over to her side, and they walked to the hut together and consulted as to the best way of destroying her brother and removing him from God’s fair world. Now it was his custom to rise at dawn, mount his horse, and go a-hunting, for hunting he dearly loved. So the serpent said to her, “Take to thy bed and pretend to be ill, and say to him, ‘I dreamed a dream, dear brother, and lo, I saw thee go and fetch me wolf’s milk to make me well.’ Then he’ll go and fetch it, and the wolves will tear his dogs to pieces, and then we can take and do to him as we list, for his strength is in his dogs.”

So when the brother came home from hunting the serpent hid himself, but the sister said, “I have 67 dreamed a dream, dear brother. Methought thou didst go and fetch me wolf’s milk, and I drank of it, and my health came back to me, for I am so weak that God grant I die not.”––“I’ll fetch it,” said her brother. So he mounted his horse and set off. Presently he came to a little thicket, and immediately a she-wolf came out. Then Protius ran her down and Nedviga held her fast, and the little Tsar milked her and let her go. And the she-wolf looked round and said, “Well for thee, little Tsar Novishny, that thou hast let me go. Methought thou wouldst not let me go alive. For that thou hast let me go, I’ll give thee, little Tsar Novishny, a wolf-whelp.”––Then she said to the little wolf, “Thou shalt serve this dear little Tsar as though he were thine own dear father.” Then the little Tsar went back, and now there were with him two dogs and a little wolf-whelp that trotted behind them.

Now the serpent and the false sister saw him coming from afar, and three dogs trotting behind him. And the serpent said to her, “What a sly, wily one it is! He has added another watch-dog to his train! Lie down, and make thyself out worse than ever, and ask bear’s milk of him, for the bears will tear him to pieces without doubt.” Then the serpent turned himself into a needle, and she took him up and stuck him in the wall. Meanwhile the brother dismounted from his horse and came with his dogs and the wolf to the hut, and the dogs began snuffing at the needle in the wall. And his sister said to him, “Tell me, why dost thou keep these big dogs? They let me have no rest.” Then he called to the dogs, and they sat down. And his sister said to him, “I dreamed a dream, my 68 brother. I saw thee go and search and fetch me from somewhere bear’s milk, and I drank of it, and my health came back to me.”––“I will fetch it,” said her brother.

But first of all he laid him down to sleep. Nedviga lay at his head, and Protius at his feet, and Vovchok[10] by his side. So he slept through the night, and at dawn he arose and mounted his good steed and hied him thence. Again they came to a little thicket, and this time a she-bear came out. Protius ran her down, Nedviga held her fast, and the little Tsar milked her and let her go. Then the she-bear said, “Hail to thee, little Tsar Novishny; because thou hast let me go, I’ll give thee a bear-cub.” But to the little bear she said, “Obey him as though he were thine own father.” So he set off home, and the serpent and his sister saw that four were now trotting behind him. “Look!” said the serpent, “if there are not four running behind him! Shall we never be able to destroy him? I tell thee what. Ask him to get thee hare’s milk; perhaps his beasts will gobble up the hare before he can milk it.” So he turned himself into a needle again, and she fastened him in the wall, only a little higher up, so that the dogs should not get at him. Then, when the little Tsar dismounted from his horse, he and his dogs came into the hut, and the dogs began snuffing at the needle in the wall and barked at it, but the brother knew not the cause thereof. But his sister burst into tears and said, “Why dost thou keep such monstrous dogs? Such a kennel of them makes me ill with anguish!” Then he shouted to the dogs, and 69 they sat down quite still. Then she said to him, “I am so ill, brother, that nothing will make me well but hare’s milk. Go and get it for me.”––“I’ll get it,” said he.