THE STARLING

The Starling

A Scottish Story

BY

NORMAN MACLEOD

Author of

"Reminiscences of a Highland Parish" "Character Sketches"

"The Old Lieutenant and his Son" &c. &c.

BLACKIE & SON LIMITED

LONDON AND GLASGOW

BLACKIE & SON LIMITED

50 Old Bailey, London

17 Stanhope Street, Glasgow

BLACKIE & SON (INDIA) LIMITED

Warwick House, Fort Street, Bombay

BLACKIE & SON (CANADA) LIMITED

1118 Bay Street, Toronto

Printed in Great Britain by Blackie & Son, Ltd., Glasgow

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE

Norman Macleod was born, in 1812, at Campbeltown, in Argyllshire, where his father was parish minister. Educated in Campbeltown and Campsie for a time, he entered the University of Glasgow in 1827, and in 1837 became a licensed minister of the Church of Scotland. From 1838 to 1843 ne was minister of Loudoun parish in Ayrshire, from 1843 to 1851 of Dalkeith parish, and from 1851 till his death in 1872 of the Barony Parish, Glasgow. He was appointed chaplain to Queen Victoria in 1857, and next year received the degree of D.D. from Glasgow University. He edited Good Words from its foundation in 1860 till his death, and he also gained great literary success with the following books: The Gold Thread (1861), The Old Lieutenant and his Son (1862), Parish Papers (1862), Wee Davie (1864), Eastward (1866), Reminiscences of a Highland Parish (1867), The Starling (1867), Peeps at the Far East (1871), The Temptation of Our Lord (1872), and Character Sketches (1872).

Contents

CHAP.

List of Illustrations

"Here he is! Tak' him and finish him" Frontispiece

"Are you aware, Mr. Mercer, of what has just happened?"

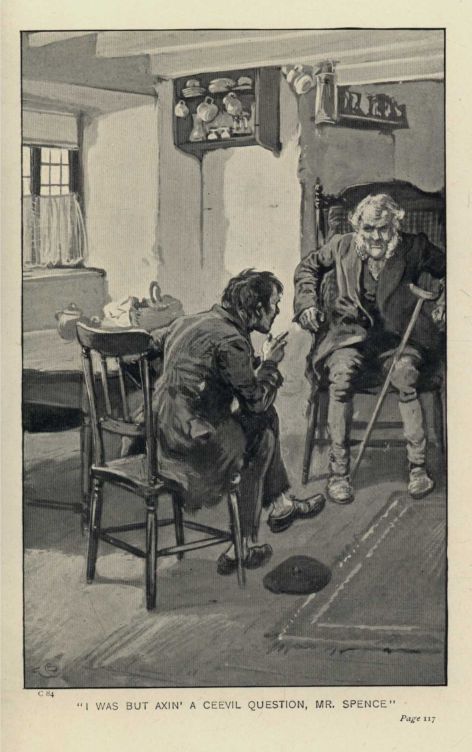

"I was but axin' a ceevil question, Mr. Spence"

THE STARLING

CHAPTER I

ANTECEDENTS

"The man was aince a poacher!" So said, or rather breathed with his hard wheezing breath, Peter Smellie, shopkeeper and elder, into the ears of Robert Menzies, a brother elder, who was possessed of a more humane disposition. They were conversing in great confidence about the important "case" of Sergeant Adam Mercer. What that case was, the reader will learn by and by. The only reply of Robert Menzies was, "Is't possible!" accompanied by a start and a steady gaze at his well-informed brother. "It's a fac' I tell ye," continued Smellie, "but ye'll keep it to yersel'--keep it to yersel', for it doesna do to injure a brither wi'oot cause; yet it's richt ye should ken what a bad beginning our freen' has had. Pit your thumb on't, however, in the meantime--keep it, as the minister says, in retentis, which I suppose means, till needed."

Smellie went on his way to attend to some parochial duty, nodding and smiling, and again admonishing his brother to "keep it to himsel'." He seemed unwilling to part with the copyright of such a spicy bit of gossip. Menzies inwardly repeated, "A poacher! wha would have thocht it? At the same time, I see----" But I will not record the harmonies, real or imaginary, which Mr. Menzies so clearly perceived between the early and latter habits of the Sergeant.

And yet the gossiping Smellie, whose nose had tracked out the history of many people in the parish of Drumsylie, was in this, as in most cases, accurately informed. The Sergeant of whom he spoke had been a poacher some thirty years before, in a district several miles off. The wonder was how Smellie had discovered the fact, or how, if true, it could affect the present character or position of one of the best men in the parish. Yet true it was, and it is as well to confess it, not with the view of excusing it, but only to account for Mercer's having become a soldier, and to show how one who became "meek as a sheathed sword" in his later years, had once been possessed of a very keen and ardent temperament, whose ruling passion was the love of excitement, in the shape of battle with game and keepers. I accidentally heard the whole story, which, on account of other circumstances in the Sergeant's later history, interested me more than I fear it may my readers.

Mercer did not care for money, nor seek to make a trade of the unlawful pleasure of shooting without a licence. Nor in the district in which he lived was the offence then looked upon in a light so very disreputable as it is now; neither was it pursued by the same disreputable class. The sport itself was what Mercer loved for its own sake, and it had become to him quite a passion. For two or three years he had frequently transgressed, but he was at last caught on the early dawn of a summer's morning by John Spence, the gamekeeper of Lord Bennock. John had often received reports from the underkeeper and watchers, of some unknown and mysterious poacher who had hitherto eluded every attempt to seize him. Though rather too old for very active service, Spence resolved to concentrate all his experience--for, like many a thoroughbred keeper, he had himself been a poacher in his youth--to discover and secure the transgressor; but how he did so it would take pages to tell. Adam never suspected John of troubling himself about such details as that of watching poachers, and John never suspected that Adam was the poacher. The keeper, we may add, was cousin-german to Mercer's mother. The capture itself was not difficult; for John, having lain in wait, suddenly confronted Adam, who, scorning the idea of flying, much more of struggling with his old cousin, quietly accosted him with, "Weel, John, ye hae catched me at last."

"Adam Mercer!" exclaimed the keeper, with a look of horror. "It canna be you! It's no' possible!"

"It's just me, John, and no mistak'," said Adam, quietly throwing himself down on the heather, and twisting a bit about his finger. "For better or waur, I'm in yer power; but had I been a ne'er-do-weel, like Willy Steel, or Tam M'Grath, I'd hae blackened my face, and whammel'd ye ower and pit yer head in a wallee afore ye could cheep as loud as a stane-chucker; but when I saw wha ye war, I gied in."

"I wad raither than a five-pun-note I had never seen yer face! Keep us! what's to be dune! What wull yer mither say? and his Lordship? Na, what wull onybody say wi' a spark o' decency when they hear----"

"Dinna fash yer thoomb, John; tak' me and send me to the jail."

"The jail! What gude will that do to you or me, laddie? I'm clean donnered about the business. Let me sit down aside ye; keep laigh, in case the keepers see ye, and tell me by what misshanter ye ever took to this wicked business, and under my nose, as if I couldna fin' ye oot!"

"Sport, sport!" was Mercer's reply. "Ye ken, John, I'm a shoemaker, and it's a dull trade, and squeezing the clams against the wame is ill for digestion; and when that fails, ane's speerits fail, and the warld gets black and dowie; and whan things gang wrang wi' me, I canna flee to drink: but I think o' the moors that I kent sae weel when my faither was a keeper to Murray o' Cultrain. Ye mind my faither? was he no' a han' at a gun!"

"He was that--the verra best," said John.

"Aweel," continued Adam, "when doon in the mouth, I ponder ower the braw days o' health and life I had when carrying his bag, and getting a shot noos and thans as a reward; and it's a truth I tell ye, that the whirr kick-ic-ic o' a covey o' groose aye pits my bluid in a tingle. It's a sort o' madness that I canna accoont for; but I think I'm no responsible for't. Paitricks are maist as bad, though turnips and stubble are no' to be compared wi' the heather, nor walkin' amang them like the far-aff braes, the win'y taps o' the hills, or the lown glens. Mony a time I hae promised to drap the gun and stick to the last; but when I'm no' weel, and wauken and see the sun glintin', and think o' the wide bleak muirs, and the fresh caller air o' the hill, wi' the scent o' the braes an' the bog myrtle, and thae whirrin' craturs--man, I canna help it! I spring up and grasp the gun, and I'm aff!"

The reformed poacher and keeper listened with a poorly-concealed smile, and said, "Nae doot, nae doot, Adam, it's a' natural--I'm no denyin' that; it's a glorious business; in fac', it's jist pairt o' every man that has a steady han' and a guid e'e and a feeling heart. Ay, ay. But, Adam, were ye no' frichtened?"

"For what?"

"For the keepers!"

"The keepers! Eh, John, that's half the sport! The thocht o' dodgin' keepers, jinkin' them roon' hills, and doon glens, and lyin' amang the muir-hags, and nickin' a brace or twa, and then fleein' like mad doon ae brae and up anither; and keekin' here, and creepin' there, and cowerin' alang a fail dyke, and scuddin' thro' the wood--that's mair than half the life o't, John! I'm no sure if I could shoot the birds if they were a' in my ain kailyard, and my ain property, and if I paid for them!"

"But war ye no' feared for me that kent ye?" asked John.

"Na!" replied Adam, "I was mair feared for yer auld cousin, my mither, gif she kent what I was aboot, for she's unco' prood o' you. But I didna think ye ever luiked efter poachers yersel'? Noo I hae telt ye a' aboot it."

"I' faith," said John, taking a snuff and handing the box to Adam, "it's human natur'! But ye ken, human natur's wicked, desperately wicked! and afore I was a keeper my natur' was fully as wicked as yours,--fully, Adam, if no waur. But I hae repented--ever sin' I was made keeper; and I wadna like to hinder your repentance. Na, na. We mauna be ower prood! Sae I'll---- Wait a bit, man, be canny till I see if ony o' the lads are in sicht;" and John peeped over a knoll, and cautiously looked around in every direction until satisfied that he was alone. "--I'll no' mention this job," he continued, "if ye'll promise me, Adam, never to try this wark again; for it's no' respectable; and, warst o' a', it's no' safe, and ye wad get me into a habble as weel as yersel'. Sae promise me, like a guid cousin, as I may ca' ye,--and bluid is thicker than water, ye ken,--and then just creep doon the burn, and alang the plantin', and ower the wa', till ye get intil the peat road, and be aff like stoor afore the win'; but I canna wi' conscience let ye tak' the birds wi' ye."

Adam thought a little, and said, "Ye're a gude sowl, John, and I'll no' betray ye." After a while he added, gravely, "But I maun kill something. It's no in my heart as wickedness; but my fingers maun draw a trigger." After a pause, he continued, "Gie's yer hand, John; ye hae been a frien' to me, and I'll be a man o' honour to you. I'll never poach mair, but I'll 'list and be a sodger! Till I send hame money,--and it'ill no' be lang,--be kind tae my mither, and I'll never forget it."

"A sodger!" exclaimed John.

But Adam, after seizing John by the hand and saying, "Fareweel for a year and a day," suddenly started off down the glen, leaving two brace of grouse, with his gun, at John's feet; as much as to say, Tell my Lord how you caught the wicked poacher, and how he fled the country.

Spence told indeed how he had caught a poacher, who had escaped, but never gave his name, nor ever hinted that Adam was the man.

It was thus Adam Mercer poached and enlisted.

One evening I was at the house of a magistrate with whom I was acquainted, when a man named Andrew Dick called to get my friend's signature to his pension paper, in the absence of the parish minister. Dick had been through the whole Peninsular campaign, and had retired as a corporal. I am fond of old soldiers, and never fail when an opportunity offers to have a talk with them about "the wars". On the evening in question, my friend Findlay, the magistrate, happened to say in a bluff kindly way, "Don't spend your pension in drink."

Dick replied, saluting him, "It's very hard, sir, that after fighting the battles of our country, we should be looked upon as worthless by gentlemen like you."

"No, no, Dick, I never said you were worthless," was the reply.

"Please your honour," said Dick, "ye did not say it, but I consider any man who spends his money in drink is worthless; and, what is mair, a fool; and, worse than all, is no Christian. He has no recovery in him, no supports to fall back on, but is in full retreat, as we would say, from common decency."

"But you know," said my friend, looking kindly on Dick, "the bravest soldiers, and none were braver than those who served in the Peninsula, often exceeded fearfully--shamefully; and were a disgrace to humanity."

"Well," replied Dick, "it's no easy to make evil good, and I won't try to do so; but yet ye forget our difficulties and temptations. Consider only, sir, that there we were, not in bed for months and months; marching at all hours; ill-fed, ill-clothed, and uncertain of life--which I assure your honour makes men indifferent to it; and we had often to get our mess as we best could,--sometimes a tough steak out of a dead horse or mule, for when the beast was skinned it was difficult to make oot its kind; and after toiling and moiling, up and down, here and there and everywhere, summer and winter, when at last we took a town with blood and wounds, and when a cask of wine or spirits fell in the way of the troops, I don't believe that you, sir, or the justices of the peace, or, with reverence be it spoken, the ministers themselves, would have said 'No', to a drop. You'll excuse me, sir; I'm perhaps too free with you."

"I didn't mean to lecture you, or to blame you, Dick, for I know the army is not the place for Christians."

"Begging your honour's pardon, sir," said Dick, "the best Christians I ever knowed were in the army--men who would do their dooty to their king, their country, and their God."

"You have known such?" I asked, breaking into the conversation, to turn it aside from what threatened to be a dispute.

"I have, sir! There's ane Adam Mercer, in this very parish, an elder of the Church--I'm a Dissenter mysel', on principle, for I consider----"

"Go on, Dick, about Mercer; never mind your Church principles."

"Well, sir, as I was saying--though, mind you, I'm not ashamed of being a Dissenter, and, I houp, a Christian too--Adam was our sergeant; and a worthier man never shouldered a bayonet. He was nae great speaker, and was quiet as his gun when piled; but when he shot, he shot! that did he, short and pithy, a crack, and right into the argument. He was weel respeckit, for he was just and mercifu'--never bothered the men, and never picked oot fauts, but covered them; never preached, but could gie an advice in two or three words that gripped firm aboot the heart, and took the breath frae ye. He was extraordinar' brave! If there was any work to do by ordinar', up to leading a forlorn hope, Adam was sure to be on't; and them that kent him even better than I did then, said that he never got courage frae brandy, but, as they assured me, though ye'll maybe no' believe it, his preparation was a prayer! I canna tell hoo they fan' this oot, for Adam was unco quiet; but they say a drummer catched him on his knees afore he mounted the ladder wi' Cansh at the siege o' Badajoz, and that Adam telt him no' to say a word aboot it, but yet to tak' his advice and aye to seek God's help mair than man's."

This narrative interested me much, so that I remembered its facts, and connected them with what I afterwards heard about Adam Mercer many years ago, when on a visit to Drumsylie.

CHAPTER II

THE ELDER AND HIS STARLING

When Adam Mercer returned from the wars, more than half a century ago, he settled in the village of Drumsylie, situated in a county bordering on the Highlands, and about twenty miles from the scene of his poaching habits, of which he had long ago repented. His hot young blood had been cooled down by hard service, and his vehement temperament subdued by military discipline; but there remained an admirable mixture in him of deepest feeling, regulated by habitual self-restraint, and expressed in a manner outwardly calm but not cold, undemonstrative but not unkind. His whole bearing was that of a man accustomed at once to command and to obey. Corporal Dick had not formed a wrong estimate of his Christianity. The lessons taught by his mother, whom he fondly loved, and whom he had in her widowhood supported to the utmost of his means from pay and prize-money, and her example of a simple, cheerful, and true life, had sunk deeper than he knew into his heart, and, taking root, had sprung up amidst the stormy scenes of war, bringing forth the fruits of stern self-denial and moral courage tempered by strong social affections.

Adam had resumed his old trade of shoemaker. He occupied a small cottage, which, with the aid of a poor old woman in the neighbourhood, who for an hour morning and evening did the work of a servant, he kept with singular neatness. His little parlour was ornamented with several memorials of the war--a sword or two picked up on memorable battle-fields; a French cuirass from Waterloo, with a gaudy print of Wellington, and one also of the meeting with Blücher at La Belle Alliance.

The Sergeant attended the parish church as regularly as he used to do parade. Anyone could have set his watch by the regularity of his movements on Sunday mornings. At the same minute on each succeeding day of holy rest and worship, the tall, erect figure, with well-braced shoulders, might be seen stepping out of the cottage door--where he stood erect for a moment to survey the weather--dressed in the same suit of black trousers, brown surtout, buff waistcoat, black stock, white cotton gloves, with a yellow cane under his arm--everything so neat and clean, from the polished boots to the polished hat, from the well-brushed grey whiskers to the well-arranged locks that met in a peak over his high forehead and soldier-like face. And once within the church there was no more sedate or attentive listener.

There were few week-days and no Sunday evenings on which the Sergeant did not pay a visit to some neighbour confined to bed from sickness, or suffering from distress of some kind. He manifested rare tact--made up of common sense and genuine benevolence--on such occasions. His strong sympathies put him instantly en rapport with those whom he visited, enabling him at once to meet them on some common ground. Yet in whatever way the Sergeant began his intercourse, whether by listening patiently--and what a comfort such listening silence is!--to the history of the sickness or the sorrow which had induced him to enter the house, or by telling some of his own adventures, or by reading aloud the newspaper--he in the end managed with perfect naturalness to convey truths of weightiest import, and fraught with enduring good and comfort--all backed up by a humanity, an unselfishness, and a gentleman-like respect for others, which made him a most welcome guest. The humble were made glad, and the proud were subdued--they knew not how, nor probably did the Sergeant himself, for he but felt aright and acted as he felt, rather than endeavoured to devise a plan as to how he should speak or act in order to produce a definite result. He numbered many true friends; but it was not possible for him to avoid being secretly disliked by those with whom, from their character, he would not associate, or whom he tacitly rebuked by his own orderly life and good manners.

Two events, in no way connected, but both of some consequence to the Sergeant, turned the current of his life after he had resided a few years in Drumsylie. One was, that by the unanimous choice of the congregation, to whom the power was committed by the minister and his Kirk Session, Mercer was elected to the office of elder in the parish.[#] This was a most unexpected compliment, and one which the Sergeant for a time declined; indeed, he accepted it only after many arguments addressed to his sense of duty, and enforced by pressing personal reasons brought to bear on his kind heart by his minister, Mr. Porteous.

[#] Every congregation in the Church of Scotland is governed by a court, recognized by civil law, composed of the minister, who acts as "Moderator", and has only a casting vote, and elders ordained to the office, which is for life. This court determines, subject to appeal to higher courts, who are to receive the Sacrament, and all cases of Church discipline. No lawyer is allowed to plead in it. Its freedom from civil consequences is secured by law. In many cases it also takes charge of the poor. The eldership has been an unspeakable blessing to Scotland.

The other event, of equal--may we not safely say of greater importance to him?--was his marriage! We need not tell the reader how this came about; or unfold all the subtle magic ways by which a woman worthy to be loved loosed the cords that had hitherto tied up the Sergeant's heart; or how she tapped the deep well of his affections into which the purest drops had for years been falling, until it gushed out with a freshness, fulness, and strength, which are, perhaps, oftenest to be found in an old heart, when it is touched by one whom it dares to love, as that old heart of Adam Mercer's must do if it loved at all.

Katie Mitchell was out of her teens when Adam, in a happy moment of his life, met her in the house of her widowed mother, who had been confined to a bed of feebleness and pain for years, and whom she had tended with a patience, cheerfulness, and unwearied goodness which makes many a humble and unknown home a very Eden of beauty and peace. Her father had been a leading member of a very strict Presbyterian body, called the "Old Light", in which he shone with a brightness which no Church on earth could of itself either kindle or extinguish, and which, when it passed out of the earthly dwelling, left a subdued glory behind it which never passed away. "Faither" was always an authority with Katie and her mother, his ways a constant teaching, and his words were to them as echoes from the Rock of Ages.

The marriage took place after the death of Kate's mother, and soon after Adam had been ordained to the eldership.

A boy was born to the worthy couple, and named Charles, after the Sergeant's father.

It was a sight to banish bachelorship from the world, to watch the joy of the Sergeant with Charlie from the day he experienced the new and indescribable feelings of being a father, until the flaxen-haired blue-eyed boy was able to toddle to his waiting arms, and then be mounted on his shoulders, while he stepped round the room to the tune of the old familiar regimental march, performed by him with half-whistle half-trumpet tones, which vainly expressed the roll of the band that crashed harmoniously in memory's ear. Katie "didna let on" her motherly pride and delight at the spectacle, which never became stale or common-place.

Adam had a weakness for pets. Dare we call such tastes a weakness, and not rather a minor part of his religion, which included within its wide embrace a love of domestic animals, in which he saw, in their willing dependence on himself, a reflection of more than they could know, or himself even fully understand? At the time we write a starling was his special friend. It had been caught and tamed for his boy Charlie. Adam had taught the creature with greatest care to speak with precision. Its first and most important lesson, was, "I'm Charlie's bairn". And one can picture the delight with which the child heard this innocent confession, as the bird put his head askance, looked at him with his round full eye, and in clear accents acknowledged his parentage: "I'm Charlie's bairn!" The boy fully appreciated his feathered confidant, and soon began to look upon him as essential to his daily enjoyment. The Sergeant had also taught the starling to repeat the words, "A man's a man for a' that", and to whistle a bar or two of the ditty, "Wha'll be king but Charlie!"

Katie had more than once confessed that she "wasna unco' fond o' this kind o' diversion". She pronounced it to be "neither natural nor canny", and had often remonstrated with the Sergeant for what she called his "idle, foolish, and even profane" painstaking in teaching the bird. But one night, when the Sergeant announced that the education of the starling was complete, she became more vehement than usual on this assumed perversion of the will of Providence.

"Nothing," said the Sergeant, "can be more beautiful than his 'A man's a man for a' that'."

"The mair's the pity, Adam!" said Katie. "It's wrang--clean wrang--I tell ye; and ye'll live tae rue't. What right has he to speak? cock him up wi' his impudence! There's mony a bairn aulder than him canna speak sae weel. It's no' a safe business, I can tell you, Adam."

"Gi' ower, gi' ower, woman," said the Sergeant; "the cratur' has its ain gifts, as we hae oors, and I'm thankfu' for them. It does me mair gude than ye ken whan I tak' the boy on my lap, and see hoo his e'e blinks, and his bit feet gang, and hoo he laughs when he hears the bird say, 'I'm Charlie's bairn'. And whan I'm cuttin', and stitchin', and hammerin', at the window, and dreamin' o' auld langsyne, and fechtin' my battles ower again, and when I think o' that awfu' time that I hae seen wi' brave comrades noo lying in some neuk in Spain; and when I hear the roar o' the big guns, and the splutterin' crackle o' the wee anes, and see the crood o' red coats, and the flashin' o' bagnets, and the awfu' hell--excuse me--o' the fecht, I tell you it's like a sermon to me when the cratur' says 'A man's a man for a' that!'" The Sergeant would say this, standing up, and erect, with one foot forward as if at the first step of the scaling ladder. "Mind ye, Katie, that it's no' every man that's 'a man for a' that'; but mair than ye wad believe are a set o' fushionless, water-gruel, useless cloots, cauld sooans, when it comes to the real bit--the grip atween life and death! O ye wad wunner, woman, hoo mony men when on parade, or when singin' sangs aboot the war, are gran' hands, but wha lie flat as scones on the grass when they see the cauld iron! Gie me the man that does his duty, whether he meets man or deevil--that's the man for me in war or peace; and that's the reason I teached the bird thae words. It's a testimony for auld freends that I focht wi', and that I'll never forget--no, never! Dinna be sair, gudewife, on the puir bird."--"Eh, Katie," he added, one night, when the bird had retired to roost, "just look at the cratur'! Is'na he beautifu'? There he sits on his bawk as roon' as a clew, wi' his bit head under his wing, dreamin' aboot the wuds maybe--or aboot wee Charlie--or aiblins aboot naething. But he is God's ain bird, wonderfu' and fearfully made."

Still Katie, feeling that "a principle"--as she, à la mode, called her opinion--was involved in the bird's linguistic habits, would still maintain her cause with the same arguments, put in a variety of forms. "Na, na, Adam!" she would persistingly affirm, "I will say that for a sensible man an' an elder o' the kirk, ye're ower muckle ta'en up wi' that cratur'. I'll stick to't, that it's no' fair, no' richt, but a mockery o' man. I'm sure faither wadna hae pitten up wi't!"

"Dinna be flyting on the wee thing wi' its speckled breast and bonnie e'e. Charlie's bairn, ye ken--mind that!"

"I'm no flyting on him, for it's you, no' him, that's wrang. Mony a time when I spak' to you mysel', ye were as deaf as a door nail to me, and can hear naething in the house but that wee neb o' his fechting awa' wi' its lesson. Na, ye needna glower at me, and look sae astonished, for I'm perfect serious."

"Ye're speaking perfect nonsense, gudewife, let me assure you; and I am astonished at ye," replied Adam, resuming his work on the bench.

"I'm no sic' a thing, Adam, as spakin' nonsense," retorted his wife, sitting down with her seam beside him. "I ken mair aboot they jabbering birds maybe than yersel'. For I'll never forget an awfu' job wi' ane o' them that made a stramash atween Mr. Carruthers, our Auld Licht minister, and Willy Jamieson the Customer Weaver. The minister happened to be veesitin' in Willy's house, and exhortin' him and some neebours that had gaithered to hear. Weel, what hae ye o't, but ane o' thae parrots, or Kickcuckkoo birds--or whatever ye ca' them--had been brocht hame by Willy's brither's son--him that was in the Indies--and didna this cratur' cry oot 'Stap yer blethers!' just ahint the minister, wha gied sic a loup, and thocht it a cunning device o' Satan!"

"Gudewife, gudewife!" struck in the Sergeant, as he turned to her with a laugh, "O dinna blether yoursel', for ye never did it afore. They micht hae hung the birdcage oot while the minister was in. But what had the puir bird to do wi' Satan or religion? Wae's me for the religion that could be hurt by a bird's cracks! The cratur' didna ken what it was saying."

"Didna ken what it was saying!" exclaimed Katie, with evident amazement. "I tell ye, I've see'd it mony a time, and heard it, too; and it was a hantle sensibler than maist bairns ten times its size. I was watchin' it that day when it disturbed Mr. Carruthers, and I see'd it lookin' roon', and winkin' its een, and scartin' its head lang afore it spak'; and it tried its tongue--and black it was, as ye micht expek, and dry as ben leather--three or four times afore it got a soond out; and tho' a' the forenoon it had never spak a word, yet when the minister began, its tongue was lowsed, and it yoked on him wi' its gowk's sang, 'Stap yer blethers, stap yer blethers!' It was maist awfu' tae hear't! I maun alloo, hooever, that it cam' frae a heathen land, an wasna therefore sae muckle to be blamed. But I couldna mak' the same excuse for your bird, Adam!"

A loud laugh from Adam proved at once to Katie that she had neither offended nor convinced him by her arguments.

But all real or imaginary differences between the Sergeant and his wife about the starling, ended with the death of their boy. What that was to them both, parents only who have lost a child--an only child--can tell. It "cut up", as they say, the Sergeant terribly. Katie seemed suddenly to become old. She kept all her boy's clothes in a press, and it was her wont for a time to open it as if for worship, every night, and to "get her greet out". The Sergeant never looked into it. Once, when his wife awoke at night and found him weeping bitterly, he told his first and only fib; for he said that he had an excruciating headache. A headache! He would no more have wept for a headache of his own than he would for one endured by his old foe, Napoleon.

This great bereavement made the starling a painful but almost a holy remembrancer of the child. "I'm Charlie's bairn!" was a death-knell in the house. When repeated, no comment was made. It was generally heard in silence; but one day, Adam and his wife were sitting at the fireside taking their meal in a sad mood, and the starling, perhaps under the influence of hunger, or--who knows?--from an uneasy instinctive sense of the absence of the child, began to repeat rapidly the sentence, "I'm Charlie's bairn!" The Sergeant rose and went to its cage with some food, and said, with as much earnestness as if the bird had understood him, "Ay, ye're jist his bairn, and ye'll be my bairn tae as lang as ye live!"

"A man's a man for a' that!" quoth the bird.

"Sometimes no'," murmured the Sergeant.

CHAPTER III

THE STARLING A DISTURBER OF THE PEACE

It was a beautiful Sunday morning in spring. The dew was glittering on every blade of grass; the trees were bursting into buds for coming leaves, or into flower for coming fruit; the birds were "busy in the wood" building their nests, and singing jubilate; the streams were flashing to the sea; the clouds, moisture laden, were moving across the blue heavens, guided by the winds; and signs of life, activity, and joy filled the earth and sky.

The Sergeant hung out Charlie in his cage to enjoy the air and sunlight. He had not of late been so lively as usual; his confession as to his parentage was more hesitating; and when giving his testimony as to a man being a man, or as to the exclusive right of Charlie to be king, he often paused as if in doubt. All his utterances were accompanied by a spasmodic chirp and jerk, evidencing a great indifference to humanity. A glimpse of nature might possibly recover him. And so it did; for he had not been long outside before he began to spread his wings and tail feathers to the warm sun, and to pour out more confessions and testimonies than had been heard for weeks.

Charlie soon gathered round him a crowd of young children with rosy faces and tattered garments who had clattered down from lanes and garrets to listen to his performances. Every face in the group became a picture of wonder and delight, as intelligible sounds were heard coming from a hard bill; and any one of the crowd would have sold all he had on earth--not a great sacrifice after all, perhaps a penny--to possess such a bird. "D'ye hear it, Archy?" a boy would say, lifting up his little brother on his shoulder, to be near the cage. Another would repeat the words uttered by the distinguished speaker, and direct attention to them. Then, when all were hushed into silent and eager expectancy awaiting the next oracular statement, and the starling repeated "I'm Charlie's bairn!" and whistled "Wha'll be king but Charlie!" a shout of joyous merriment followed, with sundry imitations of the bird's peculiar guttural and rather rude pronunciation. "It's a witch, I'll wager!" one boy exclaimed. "Dinna say that," replied another, "for wee Charlie's dead." Yet it would be difficult to trace any logical contradiction between the supposed and the real fact.

This audience about the cage was disturbed by the sudden and unexpected appearance from round the corner, of a rather portly man, dressed in black clothes; his head erect; his face intensely grave; an umbrella, handle foremost, under his right arm; his left arm swinging like a pendulum; a pair of black spats covering broad flat feet, that advanced with the regular beat of slow music, and seemed to impress the pavement with their weight. This was the Rev. Daniel Porteous, the parish minister.

No sooner did he see the crowd of children at the elder's door than he paused for a moment, as if he had unexpectedly come across the execution of a criminal; and no sooner did the children see him, than with a terrified shout of "There's the minister!" they ran off as if they had seen a wild beast, leaving one or two of the younger ones sprawling and bawling on the road, their natural protectors being far too intent on saving their own lives, to think of those of their nearest relatives.

The sudden dispersion of these lambs by the shepherd soon attracted the attention of their parents; and accordingly several half-clad, slatternly women rushed from their respective "closes". Flying to the rescue of their children, they carried some and dragged others to their several corners within the dark caves. But while rescuing their wicked cubs, they religiously beat them, and manifested their zeal by many stripes and not a few admonitions:--"Tak' that--and that--and that--ye bad--bad--wicked wean! Hoo daur ye! I'll gie ye yer pay! I'll mak' ye! I'se warrant ye!" &c. &c. These were some of the motherly teachings to the terrified babes; while cries of "Archie!" "Peter!" "Jamie!" with threatening shakes of the fist, and commands to come home "immeditly", were addressed to the elder ones, who had run off to a safe distance. One tall woman, whose brown hair escaped from beneath a cap black enough to give one the impression that she had been humbling herself in sackcloth and ashes, proved the strength of her convictions by complaining very vehemently to Mr. Porteous of the Sergeant for having thrown such a temptation as the starling in the way of her children, whom she loved so tenderly and wished to bring up so piously. All the time she held a child firmly by the hand, who attempted to hide its face and tears from the minister. Her zeal we must assume was very real, since her boy had clattered off from the cage on shoes made by the Sergeant, which his mother had never paid for, nor was likely to do now, for conscience' sake, on account of this bad conduct of the shoemaker. We do not affirm that Mrs. Dalrymple never liquidated her debts, but she did so after her own fashion.

It was edifying to hear other mothers declare their belief that their children had been at the morning Sabbath School, and express their wonder and anger at discovering for the first time their absence from it; more especially as this--the only day, of course, on which it had occurred--should be the day that the minister accidentally passed to church along their street!

The minister listened to the story of their good intentions, and of the ill doings of his elder with an uneasy look, but promised speedy redress.

CHAPTER IV

THE REV. DANIEL PORTEOUS

Mr. Porteous had been minister of the parish for upwards of thirty years. Previously he had been tutor in the family of a small laird who had political interest in those old times, and through whose influence with the patron of the parish he had obtained the living of Drumsylie. He was a man of unimpeachable character. No one could charge him with any act throughout his whole life inconsistent with the "walk and conversation" becoming his profession. He performed all the duties of his office with the regularity of a well-adjusted, well-oiled machine. He visited the sick, and spoke the right words to the afflicted, the widow, and the orphan, very much in the same calm, regular, and orderly manner in which he addressed the Presbytery or wrote out a minute of Kirk Session. Never did a man possess a larger or better-assorted collection of what he called "principles" in the carefully-locked cabinet of his brain, applicable at any moment to any given ecclesiastical or theological question which was likely to come before him. He made no distinction between "principles" and his own mere opinions. The dixit of truth and the dixit of Porteous were looked upon by him as one. He had never been accused of error on any point, however trivial, except on one occasion when, in the Presbytery, a learned clerk of great authority interrupted a speech of his by suggesting that their respected friend was speaking heresy. Mr. Porteous exclaimed, to the satisfaction of all, "I was not aware of it, Moderator! but if such is the opinion of the Presbytery, I have no hesitation in instantly withdrawing my unfortunate and unintentional assertion". His mind ever after was a round, compact ball of logically spun theological worsted, wound up, and "made up". The glacier, clear, cold, and stern, descends into the valley full of human habitations, corn-fields, and vineyards, with flowers and fruit-trees on every side; and though its surface melts occasionally, it remains the glacier still. So it had hitherto been with him. He preached the truth--truth which is the world's life and which stirs the angels--but too often as a telegraphic wire transmits the most momentous intelligence: and he grasped it as a sparrow grasps the wire by which the message is conveyed. The parish looked up to him, obeyed him, feared him, and so respected him that they were hardly conscious of not quite loving him. Nor was he conscious of this blank in their feelings; for feelings and tender affections were in his estimation generally dangerous and always weak commodities,--a species of womanly sentimentalism, and apt sometimes to be rebellious against his "principles", as the stream will sometimes overflow the rocky sides that hem it in and direct its course. It would be wrong to deny that he possessed his own "fair humanities". He had friends who sympathised with him; and followers who thankfully accepted him as a safe light to guide them, as one stronger than themselves to lean on, and as one whose word was law to them. To all such he could be bland and courteous; and in their society he would even relax, and indulge in such anecdotes and laughter as bordered on genuine hilarity. As to what was deepest and truest in the man we know not, but we believe there was real good beneath the wood, hay, and stubble of formalism and pedantry. There was doubtless a kernel within the hard shell, if only the shell could be cracked. Might not this be done? We shall see.

It was this worthy man who, after visiting a sick parishioner, suddenly came round the corner of the street in which the Sergeant lived. He was, as we said, on his way to church, and the bell had not yet begun to ring for morning worship. Before entering the Sergeant's house (to do which, after the scene he had witnessed, was recognized by him to be an important duty), he went up to the cage to make himself acquainted with all the facts of the case, so as to proceed with it regularly. He accordingly put on his spectacles and looked at the bird, and the bird, without any spectacles, returned the inquiring gaze with most wonderful composure. Walking sideways along his perch, until near the minister, he peered at him full in the face, and confessed that he was Charlie's bairn. Then, after a preliminary kic and kirr, as if clearing his throat, he whistled two bars of the air, "Wha'll be king but Charlie!" and, concluding with his aphorism, "A man's a man for a' that!" he whetted his beak and retired to feed in the presence of the Church dignitary.

"I could not have believed it!" exclaimed the minister, as he walked into the Sergeant's house, with a countenance by no means indicating the sway of amiable feelings.

CHAPTER V

THE SERGEANT AND HIS STARLING IN TROUBLE

The Sergeant and his wife, after having joined, as was their wont, in private morning worship, had retired, to prepare for church, to their bedroom in the back part of the cottage, and the door was shut. Not until a loud knock was twice repeated on the kitchen-table, did the Sergeant emerge in his shirt-sleeves to reply to the summons. His surprise was great as he exclaimed, "Mr. Porteous! can it be you? Beg pardon, sir, if I have kept you waiting; please be seated. No bad news, I hope?"

Mr. Porteous, with a cold nod, and remaining where he stood, pointed with his umbrella to the cage hanging outside the window, and asked the Sergeant if that was his bird.

"It is, sir," replied the Sergeant, more puzzled than ever; "it is a favourite starling of mine, and I hung it out this morning to enjoy the air, because----"

"You need not proceed, Mr. Mercer," interrupted the minister; "it is enough for me to know from yourself that you acknowledge that bird as yours, and that you hung it there."

"There is no doubt about that, sir; and what then? I really am puzzled to know why you ask," said the Sergeant.

"I won't leave you long in doubt upon that point," continued the minister, more stern and calm if possible than before, "nor on some others which it involves."

Katie, at this crisis of the conversation, joined them in her black silk gown. She entered the kitchen wuth a familiar smile and respectful curtsey, and approached the minister, who, barely noticing her, resumed his subject. Katie, somewhat bewildered, sat down in the large chair beside the fire, watching the scene with curious perplexity.

"Are you aware, Mr. Mercer, of what has just happened?" inquired the minister.

"I do not take you up, sir," replied the Sergeant.

"Well, then, as I approached your house a crowd of children were gathered round that cage, laughing and singing, with evident enjoyment, and disturbing the neighbourhood by their riotous proceedings, thus giving pain and grief to their parents, who have complained loudly to me of the injury done to their most sacred feelings and associations by you----please, please, don't interrupt me, Mr. Mercer; I have a duty to perform, and shall finish presently."

The Sergeant bowed, folded his arms, and stood erect. Katie covered her face with her hands, and exclaimed "Tuts, tuts, I'm real sorry--tuts."

"I went up to the cage," said Mr. Porteous, continuing his narrative, "and narrowly inspected the bird. To my--what shall I call it? astonishment? or shame and confusion?--I heard it utter such distinct and articulate sounds as convinced me beyond all possibility of doubt--yet you smile, sir, at my statement!--that----"

"Tuts, Adam, it's dreadfu'!" ejaculated Katie.

"That the bird," continued the minister, "must have been either taught by you, or with your approval: and having so instructed this creature, you hang it out on this, the Sabbath morning, to whistle and to speak, in order to insult--yes, sir, I use the word advisedly----"

"Never, sir!" said the Sergeant, with a calm and firm voice; "never, sir, did I intentionally insult mortal man."

"I have nothing to do with your intentions, but with facts; and the fact is, you did insult, sir, every feeling the most sacred, besides injuring the religious habits of the young. You did this, an elder--my elder, this day, to the great scandal of religion."

The Sergeant never moved, but stood before his minister as he would have done before his general, calm, in the habit of respectful obedience to those having authority. Poor Katie acted as a sort of chorus at the fireside.

"I never thocht it would come to this," she exclaimed, twisting her fingers. "Oh! it's a pity! Sirs a day! Waes me! Sic a day as I have lived to see! Speak, Adam!" at length she said, as if to relieve her misery.

The silence of Adam so far helped the minister as to give him time to breathe, and to think. He believed that he had made an impression on the Sergeant, and that it was possible things might not be so bad as they had looked. He hoped and wished to put them right, and desired to avoid any serious quarrel with Mercer, whom he really respected as one of his best elders, and as one who had never given him any trouble or uneasiness, far less opposition. Adam, on the other hand, had been so suddenly and unexpectedly attacked, that he hardly knew for a moment what to say or do. Once or twice the old ardent temperament made him feel something at his throat, such as used to be there when the order to charge was given, or the command to form square and prepare to receive cavalry. But the habits of "drill" and the power of passive endurance came to his aid, along with a higher principle. He remained silent.

When the steam had roared off, and the ecclesiastical boiler of Mr. Porteous was relieved from extreme pressure, he began to simmer, and to be more quiet about the safety valve. Sitting down, and so giving evidence of his being at once fatigued and mollified, he resumed his discourse. "Sergeant"--he had hitherto addressed him as Mr. Mercer--"Sergeant, you know my respect for you. I will say that a better man, a more attentive hearer, a more decided and consistent Churchman, and a more faithful elder, I have not in my parish----"

Adam bowed.

"Be also seated," said the minister.

"Thank you, sir," said Adam, "I would rather stand."

"I will after all give you credit for not intending to do this evil which I complain of; I withdraw the appearance even of making any such charge," said Mr. Porteous, as if asking a question.

After a brief silence, the Sergeant said, "You have given me great pain, Mr. Porteous."

"How so, Adam?"--still more softened.

"It is great pain, sir, to have one's character doubted," said Adam.

"But have I not cause?" inquired the minister.

"You are of course the best judge, Mr. Porteous; but I frankly own to you that the possibility of there being any harm in teaching a bird never occurred to me."

"Oh, Adam!" exclaimed Katie, "I ken it was aye your mind that, but it wasna mine, although at last----"

"Let me alone, Katie, just now," quietly remarked Adam.

"What of the scandal? what of the scandal?" struck in the minister. "I have no time to discuss details this morning; the bells have commenced."

"Well, then," said the Sergeant, "I was not aware of the disturbance in the street which you have described; I never, certainly, could have intended that. I was, at the time, in the bedroom, and never knew of it. Believe me when I say't, that no man lives who would feel mair pain than I would in being the occasion of ever leading anyone to break the Lord's day by word or deed, more especially the young; and the young aboot our doors are amang the warst. And as to my showing disrespect to you, sir!--that never could be my intention."

"I believe you, Adam, I believe you; but----"

"Ay, weel ye may," chimed in Katie, now weeping as she saw some hope of peace; "for he's awfu' taen up wi' guid, is Adam, though I say it."

"Oh, Katie; dinna, woman, fash yersel' wi' me," interpolated Adam.

"Though I say't that shouldna say't," continued Katie, "I'm sure he has the greatest respec' for you, sir. He'll do onything to please you that's possible, and to mak' amends for this great misfortun'."

"Of that I have no doubt--no doubt whatever, Mrs. Mercer," said Mr. Porteous, kindly; "and I wished, in order that he should do so, to be faithful to him, as he well knows I never will sacrifice my principles to any man, be he who he may--never!

"There is no difficulty, I am happy to say," the minister resumed, after a moment's pause, "in settling the whole of this most unpleasant business. Indeed I promised to the neighbours, who were very naturally offended, that it should never occur again; and as you acted, Adam, from ignorance--and we must not blame an old soldier too much," the minister added with a patronising smile,--"all parties will be satisfied by a very small sacrifice indeed--almost too small, considering the scandal. Just let the bird be forthwith destroyed--that is all."

Adam started.

"In any case," the minister went on to say, without noticing the Sergeant's look, "this should be done, because being an elder, and, as such, a man with grave and solemn responsibilities, you will I am sure see the propriety of at once acquiescing in my proposal, so as to avoid the temptation of your being occupied by trifles and frivolities--contemptible trifles, not to give a harsher name to all that the bird's habits indicate. But when, in addition to this consideration, these habits, Adam, have, as a fact, occasioned serious scandal, no doubt can remain in any well-constituted mind as to the necessity of the course I have suggested."

"Destroy Charlie--I mean, the starling?" enquired the Sergeant, stroking his chin, and looking down at the minister with a smile in which there was more of sorrow and doubt than of any other emotion. "Do you mean, Mr. Porteous, that I should kill him?"

"I don't mean that, necessarily, you should do it, though you ought to do it as the offender. But I certainly mean that it should be destroyed in any way, or by any person you please, as, if not the best possible, yet the easiest amends which can be made for what has caused such injury to morals and religion, and for what has annoyed myself more than I can tell. Remember, also, that the credit of the eldership is involved with my own."

"Are you serious, Mr. Porteous?" asked the Sergeant.

"Serious! Serious!--Your minister?--on Sabbath morning!--in a grave matter of this kind!--to ask if I am serious! Mr. Mercer, you are forgetting yourself."

"I ask pardon," replied the Sergeant, "if I have said anything disrespectful; but I really did not take in how the killing of my pet starling could mend matters, for which I say again, that I am really vexed, and ax yer pardon. What has happened has been quite unintentional on my part, I do assure you, sir."

"The death of the bird," said the minister, "I admit, in one serse, is a mere trifle--a trifle to you: but it is not so to me, who am the guardian of religion in the parish, and as such have pledged my word to your neighbours that this, which I have called a great scandal, shall never happen again. The least that you can do, therefore, I humbly think, as a proof of your regret at having been even the innocent cause of acknowledged evil; as a satisfaction to your neighbours, and a security against a like evil occurring again; and as that which is due to yourself as an office-bearer, to the parish, and, I must add, to me as your pastor, and my sense of what is right; and, finally, in order to avoid a triumph to Dissent on the one hand, and to infidelity on the other,--it is, I say, beyond all question your clear duty to remove the cause of the offence, by your destroying that paltry insignificant bird. I must say, Mr. Mercer, that I feel not a little surprised that your own sense of what is right does not compel you at once to acquiesce in my very moderate demand--so moderate, indeed, that I am almost ashamed to make it."

No response from the Sergeant.

"Many men, let me tell you," continued Mr. Porteous, "would have summoned you to the Kirk Session, and rebuked you for your whole conduct, actual and implied, in this case, and, if you had been contumacious, would then have libelled and deposed you!" The minister was warming as he proceeded. "I have no time," he added, rising, "to say more on this painful matter. But I ask you now, after all I have stated, and before we part, to promise me this favour--no, I won't put it on the ground of a personal favour, but on principle--promise me to do this--not to-day, of course, but on a week-day, say to-morrow--to destroy the bird,--and I shall say no more about it. Excuse my warmth, Adam, as I may be doing you the injustice of assuming that you do not see the gravity of your own position or of mine." And Mr. Porteous stretched out his hand to the Sergeant.

"I have no doubt, sir," said the Sergeant, calmly, "that you mean to do what seems to you to be right, and what you believe to be your duty. But----" and there was a pause, "but I will not deceive you, nor promise to do what I feel I can never perform. I must also do my duty, and I daurna do what seems to me to be wrang, cruel, and unnecessar'. I canna' kill the bird. It is simply impossible! Do pardon me, sir. Dinna think me disrespectful or prood. At this moment I am neither, but verra vexed to have had ony disturbance wi' my minister. Yet----"

"Yet what, Mr. Mercer?"

"Weel, Mr. Porteous, I dinna wish to detain you; but as far as I can see my duty, or understand my feelings----"

"Feelings! forsooth!" exclaimed Mr. Porteous.

"Or understand my feelings," continued Adam, "I canna--come what may, let me oot with it--I will not kill the bird!"

Mr. Porteous rose and said, in a cold, dry voice, "If such is your deliverance, so be it. I have done my duty. On you, and you only, the responsibility must now rest of what appears to me to be contumacious conduct--an offence, if possible, worse than the original one. You sin with light and knowledge--and it is, therefore, heinous by reason of several aggravations. I must wish you good-morning. This matter cannot rest here. But whatever consequences may follow, you, and you alone, I repeat, are to blame--my conscience is free. You will hear more of this most unfortunate business, Sergeant Mercer." And Mr. Porteous, with a stiff bow, walked out of the house.

Adam made a movement towards the door, as if to speak once more to Mr. Porteous, muttering to himself, "He canna be in earnest!--The thing's impossible!--It canna be!" But the minister was gone.

CHAPTER VI

THE STARLING ON HIS TRIAL

Adam was left alone with his wife. His only remark as he sat down opposite to her was: "Mr. Porteous has forgot himself, and was too quick;" adding, "nevertheless it is our duty to gang to the kirk."

"Kirk!" exclaimed Katie, walking about in an excited manner, "that's a' ower! Kirk! pity me! hoo can you or me gang to the kirk? Hoo can we be glowered at and made a speculation o', and be the sang o' the parish? The kirk! waes me; that's a' by! I never, never thocht it wad come to this wi' me or you, Adam! I think it wad hae kilt my faither. It's an awfu' chasteesement."

"For what?" quietly asked the Sergeant.

"Ye needna speer--ye ken weel eneuch it's for that bird. I aye telt ye that ye were ower fond o't, and noo!--I'm real sorry for ye, Adam. It's for you, for you, and no' for mysel', I'm sorry. Sirs me, what a misfortun'!"

"What are ye sae sorry for?" meekly inquired Adam.

"For everything!" replied Katie, groaning; "for the stramash amang the weans; for the clish-clash o' the neebors; for you and me helping to break the Sabbath; for the minister being sae angry, and that nae doubt, for he kens best, for gude reasons; and, aboon a', for you, Adam, my bonnie man, an elder o' the kirk, brocht into a' this habble for naething better than a bit bird!" And Katie threw herself into the chair, covering her face with her hands.

The Sergeant said nothing, but rose and went outside to bring in the cage. There were signs of considerable excitement in the immediate neighbourhood. The long visit of the minister in such circumstances could mean only a conflict with Adam, which would be full of interest to those miserable gossips, who never thought of attending church except on rare occasions, and who were glad of something to occupy their idle time on Sunday morning. Sundry heads were thrust from upper windows, directing their gaze to the Sergeant's house. Some of the boys reclined on the grass at a little distance, thus occupying a safe position, and commanding an excellent retreat should they be pursued by parson or parents. The cage was the centre of attraction to all.

The Sergeant at a glance saw how the enemy lay, but without appearing to pay any attention to the besiegers, he retired with the cage into the house and fixed it in its accustomed place over his boy's empty cot. When the cage was adjusted, the starling scratched the back of his head, as if something annoyed him; he then cleaned his bill on each side of the perch, as if present duties must be attended to; after this he hopped down and began to describe figures with his open bill on the sanded floor of the cage, as if for innocent recreation. Being refreshed by these varied exercises, he concluded by repeating his confession and testimony with a precision and vigour never surpassed.

Katie still occupied the arm-chair, blowing her nose with her Sunday pocket-handkerchief. The Sergeant sat down beside her.

"It's time to gang to the kirk, gudewife," he remarked, although, from the bells having stopped ringing, and from the agitated state of his wife's feelings, he more than suspected that, for the first time during many years, he would be obliged to absent himself from morning worship--a fact which would form another subject of conversation for his watchful and thoughtful neighbours.

"Hoo can we gang to the kirk, Adam, wi' this on our conscience?" muttered Katie.

"I hae naething on my conscience, Katie, to disturb it," said her husband; "and I'm sorry if onything I hae done should disturb yours. What can I do to lighten 't?"

Katie was silent.

"If ye mean," said the Sergeant, "that the bird should be killed, by a' means let it be done. I'll do onything to please you, though Mr. Porteous has, in my opinion, nae richt whatever to insist on my doin't to please him; for he kens naething aboot the cratur. But if you, that kens as weel as me a' the bird has been to us baith, but speak the word, the deed will be allooed by me. I'll never say no."

"Do yer duty, Adam!" said his wife.

"That is, my duty to you, mind, for I owe it to nane else I ken o'. But that duty shall be done--so ye've my full leave and leeberty tae kill the bird. Here he is! Tak' him oot o' the cage, and finish him. I'll no interfere, nor even look on, cost what it may." And the Sergeant took down the cage, and held it near his wife. But she said nothing, and did nothing.

"I'm Charlie's bairn!" exclaimed the starling.

"Dinna tell me, Adam, tae kill the bird! It's no' me, but you, should do sic wark. Ye're a man and a sodger, and it was you teached him, and got us into this trouble."

"Sae be't!" said the Sergeant. "I've done mair bluidy jobs in my day, and needna fear tae spill, for the sake o' peace, the wee drap bluid o' the puir h airmless thing. What way wid ye like it kilt?"

"Ye should ken best yersel', gudeman; killin' is no woman's wark," said Katie, in a low voice, as she turned her head away and looked at the wall.

"Aweel then, since ye leave it to me," replied Adam, "I'll gie him a sodger's death. It's the maist honourable, and the bit mannie deserves a' honour frae our hands, for he has done his duty pleasantly, in fair and foul, in simmer and winter, to us baith, and tae----Never heed--I'll shoot him at dawn o' day, afore he begins whistlin' for his breakfast; and he'll be buried decently. You and Mr. Porteous will no' be bothered wi' him lang. Sae as that's settled and determined, we may gang to the kirk wi' a guid conscience."

Adam rose, as if to enter his bedroom.

"What's your hurry, Adam?" asked Katie, in a half-peevish tone of voice. "Sit doon and let a body speak."

The Sergeant resumed his seat.

"I'm jist thinking," said Katie, "that ye'll maybe no' get onybody to gie ye a gun for sic a cruel job; and if ye did, the noise sae early in the morning wad frichten folk, and mak' an awfu' clash amang neeboors, and luik dreadfu' daft in an elder."

"Jock Hall has a gun I could get. But noo that I think o't, Jock himsel' will do the job, for he's fit for onything, and up tae everything except what's guid. I'll send him Charlie and the cage in the morning, afore ye rise; sae keep your mind easy," said the Sergeant, carelessly.

"I wadna trust Charlie into Jock Hall's power--the cruel ne'er-do-weel that he is! Na, na; whatever has to be done maun be done decently by yersel', gudeman," protested Katie.

"Ye said, gudewife, to Mr. Porteous," replied Adam, "that ye kent I wad do onything to please him and to gie satisfaction for this misfortun', as ye ca'ed it; and sin' you and him agree that the bird is to be kilt, I suppose I maun kill him to please ye baith; I see but ae way left o' finishing him."

"What way is that?" asked Katie.

"To thraw his bit neck."

"Doonricht cruelty," suggested Katie, "to thraw the neck o' a wee thing like that! Fie on ye, gudeman! Ye're no like yersel' the day."

"It's the only way left, unless we burn him; so I'll no' argue mair about it. There's nae use o' pittin' 't aff ony langer; the better day, the better deed. Sae here goes! It will be a' ower wi' him in a minute; and syne ye'll get peace----"

The Sergeant rose and placed the cage on a table near the window where the bird was accustomed to be fed. Charlie, in expectation of receiving food, was in a high state of excitement, and seemed anxious to please his master by repeating all his lessons as rapidly and correctly as possible. The Sergeant rolled up his white shirt-sleeves, to keep them from being soiled by the work in which he was about to be engaged. Being thus prepared, he opened the door of the cage, thrust in his hand, and seized the bird, saying, "Bid fareweel to yer mistress, my wee Charlie."

Katie sprang from her chair, and with a loud voice commanded the Sergeant to "haud his han' and let the bird alane!"

"What's wrang?" asked the Sergeant, as he shut the door of the cage and went towards his wife, who again sank back in her chair, and covered hef eyes with her pocket-handkerchief.

"Oh, Adam!" she said, "I'm a waik, waik woman. My nerves are a' gane; my head and heart are baith sair. A kind o' glamour, a temptation has come ower me, and I dinna ken what's richt or what's wrang. I wuss I may be forgie'n if I'm wrang, for the heart I ken is deceitfu' aboon a' things and desperately wicked:--but, richt or wrang, neither by you nor by ony ither body can I let that bird be kilt! I canna thole't! for I just thocht e'enoo that I seed plainly afore me our ain wee bairn that's awa'--an' oh, Adam!----"

Katie burst into a fit of weeping, and could say no more. The Sergeant hung up the cage in its old place; then going to his wife, he gently clapped her shoulder, and bending over her whispered in her ear, "Dinna ye fear, Katie, aboot Charlie's bairn!"

Katie clasped her hands round his neck and drew his grey head to her cheek, patting it fondly.

"Dry yer een, wifie," said Adam, "and feed the cratur, and syne we'll gang to the kirk in the afternoon."

He then retired to the bedroom, shut the door, and left Katie alone with her starling and her conscience--both at peace, and both whistling, each after its own fashion.

CHAPTER VII

THE SERGEANT ON HIS TRIAL

The Sergeant went to church in the afternoon, but he went alone. Katie was unable to accompany him. "She didna like," she said. But this excuse being not quite satisfactory to her conscience, she had recourse to that accommodating malady which comes to the rescue of universal Christendom when in perplexity--a headache. In her case it really existed as a fact, for she suffered from a genuine pain which she had not sufficient knowledge or fashion to call "nervous", but which, more than likely, really came under that designation. Her symptoms, as described by herself, were that "her head was bizzin' and bummin' like a bees' skep".

As the Sergeant marched to church, with his accustomed regular pace and modest look, he could, without seeming to remark it, observe an interest taken in his short journey never manifested before. An extra number of faces filled the windows near his house, and looked at him with half smile, half sneer.

There was nothing in the sermon of Mr. Porteous which indicated any wish to "preach to the times",--a temptation which is often too strong for preachers to resist who have nothing else ready or more interesting to preach about. Many in a congregation who may be deaf and blind to the Gospel, are wide-awake and attentive to gossip, from the pulpit. The good man delivered himself of an excellent sermon, which, as usual, was sound in doctrine and excellent in arrangement, with suitable introduction, "heads of discourse", and practical conclusion. His hearers, as a whole, were not of a character likely either to blame or praise the teaching, far less to be materially influenced by it. They were far too respectable and well-informed for that. They had "done the right thing" in coming to church as usual, and were satisfied. There was one remark often made in the minister's praise, that he was singularly exact in preaching forty-five minutes, and in dismissing the congregation at the hour and a half.

But there were evident signs of life in the announcement which he made at the end of this day's service. He "particularly requested a meeting of Kirk Session in the vestry after the benediction, and expressed a hope that all the elders would, if possible, attend".

Adam Mercer snuffed the battle from afar; but as it was his "duty" to obey the summons, he obeyed accordingly.

The Kirk Session, in spite of defects which attend all human institutions, including the House of Lords, with its Bench of Bishops, is one of the most useful courts in Scotland, and has contributed immensely in very many ways to improve the moral and physical condition of the people. Its members, as a rule, are the strength and comfort of the minister, and it is, generally speaking, his own fault if they are not. In the parish of Drumsylie the Session consisted of seven elders, with the Minister as "Moderator". These elders represented very fairly, on the whole, the sentiments of the congregation and parish on most questions which could come before them.

As all meetings of Kirk Session are held in private, reporters and lawyers being alike excluded, we shall not pretend to give any account of what passed at this one. The parish rumours were to the effect that the "Moderator", after having given a narrative of the occurrences of the morning, explained how many most important principles were involved in the case as it now stood--principles affecting the duty and powers of Kirk Sessions; the social economy of the parish; the liberties and influence of the Church, and the cause of Christian truth; and concluded by suggesting the appointment of two members, Mr. Smellie and Mr. Menzies, to "deal" with Mr. Mercer, and to report to the next meeting of Session. This led to a sharp discussion, in which Mr. Gordon, a proprietor in the neighbourhood, protested against any matter which "he presumed to characterise as trifling and unworthy of their grave attention", being brought before them at all. He also appealed the whole case to the next meeting of Presbytery, which unfortunately was not to take place for two months.

The Sergeant, strange to say, lost his temper when, having declared "upon his honour as a soldier" that he meant no harm, and could therefore make no apology, he was called to order by the Moderator for using such a word as "honour" in a Church court. Thinking his honour itself called in question, Adam abruptly left the meeting. Mr. Gordon, it was alleged, had been seen returning home, at one moment laughing, and the next evidently crying because of these proceedings; and more than one of the elders, it was rumoured, were disposed to join him, but were afraid of offending Mr. Porteous--a fear not unfrequently experienced in the case of many of his parishioners. The minister, it may be remarked, was fond of quoting the text, "first pure, then peaceable". But he never seemed to have attained the "first" in theory, if one might judge from his neglect of the second in practice.

It was after this meeting of Session that Mr. Smellie remarked to Mr. Menzies, as we have already recorded, that "the man was aince a poacher!" a fact which, by the way, he had communicated to Mr. Porteous also for the sake of "edification". Mr. Smellie bore a grudge towards the Sergeant, who had somehow unwittingly ruffled his vanity or excited his jealousy. He was smooth as a cat; and, like a cat, could purr, fawn, see in the dark, glide noiselessly, or make a sudden spring on his prey. The Sergeant, from certain circumstances which shall be hereafter noticed, understood his character as few in the parish did. Mr. Menzies was a different, and therefore better man, his only fault being that he believed in Smellie.

The Sergeant was later than usual in returning home. It was impossible to conceal from the inquiring and suspicious look of his wife that something was out of joint, to the extent at least of making it allowable and natural on her part to ask, "What's wrang noo, Adam?"

"Nothing particular, except wi' my honour," was the Sergeant's cool reply.

"Yer honour! What's wrang wi' that?"

"The minister," said the Sergeant, "doots it, and he tells me that it was wrang to speak aboot it."

On this, Katie, who did not quite comprehend his meaning, begged to know what had taken place. "What did they say? What did they do? Wha spak'?" And she poured out a number of questions which could not speedily be answered. We hope it will not diminish the reader's interest in this excellent woman if we admit that for a moment she, too, became the slave of gossip. We deny that this prostration of the heart and head to a mean idol is peculiar to woman--this craving for small personal talk, this love of knowledge regarding one's neighbours in those points especially which are not to their credit, or which at least are naturally desired by them to be kept secret from the world. Weak, idle, and especially vain men are as great traffickers as women in this dissocial intercourse. Like small insects, they use their small stings for annoyance, and are flattered when they make strong men wince.

Katie's fit was but momentary, and in the whole circumstances of the case excusable.

The Sergeant told her of his pass at arms, and ended with an indignant protest about his honour.

"What do they mak'," partly asserted, partly inquired Katie, "o' 'Honour to whom honour?'--and 'Honour all men?'--and 'Honour the king?'--and 'Honour faither and mither?'--what I did a' my life! I'll maintain the word is Scriptoral!"

But the Sergeant, not being critical or controversial, did not wish to contend with his wife on the connection which, as she supposed, existed between the word honour, and his word of honour. His mind was becoming perplexed and filled with painful thoughts. This antagonism into which he had been driven with those whom he had hitherto respected and followed with unhesitating confidence, was growing rapidly into a form and shape which was beyond his experience--alien to his quiet and unobtrusive disposition, and contrary to his whole purpose of life. He sat down by the fireside, and went over all the events of the day. He questioned himself as to what he had said or done to give offence to mortal man. He recalled the history of his relationship to the starling, to see, if possible, any wrong-doing in it. He reviewed the scene in the Kirk Session; and his conclusion, on the one hand, was a stone blindness as to the existence of any guilt on his part, and on the other, a strong suspicion that his minister could not do him a wrong--could not be so displeased upon unjust, ignorant, or unrighteous grounds, and that consequently there was a something--though what it was he could neither discover nor guess--which Mr. Porteous had misunderstood and had been misled by. He went over and over again the several items of this long account of debit and credit, without being able to charge aught against himself, except possibly his concealment from his minister of the reason why the starling was so much beloved, and also the fact perhaps of his having taken offence, without adequate cause, at the meeting of Session. The result of all these complex cogitations between himself and the red embers in the grate, was a resolution to go that evening to the Manse, and by a frank explanation put an end to all misunderstanding. In his pure heart the minister was reflected as a man of righteousness, love, and peace. He almost became annoyed with the poor starling, especially as it seemed to enjoy perfect ease and comfort on its perch, where it had settled for the night.

By and by he proceeded to call on the minister, but did not confide the secret to Katie.

CHAPTER VIII

THE CONFERENCE IN THE MANSE

The manse inhabited by Mr. Porteous, like most of its parochial companions at that time--for much improvement in this as in other buildings has taken place since those days--was not beautiful, either in itself or in its surroundings. Its three upper windows stared day and night on a blank hill, whose stupid outline concealed the setting, and never welcomed the rising sun. The two lower windows looked into a round plot of tawdry shrubs, surrounded by a neglected boxwood border which defended them from the path leading from the small green gate to the door; while twenty yards beyond were a few formal ugly-looking trees that darkened the house, and separated it from the arable land of the glebe. No blame to the minister for his manse or its belongings! On £200 per annum, he could not keep a gardener, or afford any expensive ornaments. And for the same reason he had never married, although his theory as to "feelings" may have possibly hindered him from taking this humanising step. And who knows what effect the small living and the bachelor life may have had on his "principles"!

His sister lived with him. To many a manse in Scotland the minister's sister has been a very angel in the house, a noble monument of devoted service and of self-sacrificing love--only surpassed by that paragon of excellence, if excellent at all, the minister's wife. But with all charity, Miss Porteous--Thomasina she was called by her father, after his brother in the West Indies, from whom money was expected, but who had left her nothing--was not in any way attractive, and never gave one the impression of self-sacrifice. She evidently felt her position to be a high one. Being next to the Bishop, she evidently considered herself an Archdeacon, Dean, or other responsible ecclesiastical personage. She was not ugly, for no woman is or can be that; but yet she was not beautiful. Being about fifty, as was guessed by the most charitable, her looks were not what they once were, nor did they hold out any hope of being improved, like wine, by age. Her hair was rufous, and the little curls which clustered around her forehead suggested, to those who knew her intimately, the idea of screws for worming their way into characters, family secrets, and similar private matters. She was, unfortunately, the minister's newspaper, his remembrancer, his spiritual detective and confidential informant as to all that belonged to the parish and its passing history.

Miss Thomasina Porteous, in the absence of the servant, who was "on leave" for a day or two, opened the door to the Sergeant. Mr. Porteous was in his study, popularly so called,--a small room, with a book-press at one end, and a table in the centre, with a desk on it, a volume of Matthew Henry's Commentary, Cruden's Concordance, an Edinburgh Almanac, and a few Reports. Beside the table, and near the fire, was an arm-chair, in which the minister sat reading a volume of sermons. No sooner was the Sergeant announced than Mr. Porteous rose, looked over his spectacles, hesitated, and at last shook hands, as if with an icicle, or in conformity with Act of Parliament. Then, motioning Mr. Mercer to a seat, he begged to inquire to what he owed this call, accompanying the questioning with a hint to Thomasina to leave the room. The Sergeant's first feeling was that he had made a great mistake, and he wished he had never left the army.

"Well, Mr. Mercer?" inquired the minister, as he sat opposite to the Sergeant.

"I am sorry to disturb you, sir," replied the Sergeant, "but I wished to say that I think I was too hot and hasty this afternoon in the Session."

"Pray don't apologise to me, Mr. Mercer," said the minister. "Whatever you have to say on that point, had better be said publicly before the Kirk Session. Anything else?"

The Sergeant wavered, as military historians would say, before this threatened opposition, as if suddenly met by a square of bristling bayonets.

"Well, then," he at last said, "I wish to tell you frankly, and in as few words as possible, what no human being kens but my wife. I never blame ignorance, and I'm no gaun to blame yours, Mr. Porteous, but----"

"My ignorance!" exclaimed the minister. "It's come to a pretty pass indeed, if you are to blame it, or remove it! Ignorance of what, pray?"

"Your ignorance, Mr. Porteous," continued the Sergeant, "on a point which I should have made known to you, and for which I alone and not you are in faut."

The minister seemed relieved by this admission.