Vol. II. Frontispiece.

A larger version of the map on page 302 can be viewed by clicking on the map in a web browser.

Additional Transcriber's Notes are at the end.

SPANISH AMERICA

THE SOUTH AMERICAN SERIES

Demy 8vo, cloth.

1. CHILE. By G. F. Scott Elliott, F.R.G.S. With an Introduction by Martin Hume, a Map, and 39 Illustrations. (4th Impression.)

2. PERU. By C. Reginald Enock, F.R.G.S. With an Introduction by Martin Hume, a Map, and 72 Illustrations. (3rd Impression.)

3. MEXICO. By C. Reginald Enock, F.R.G.S. With an Introduction by Martin Hume, a Map, and 64 Illustrations. (3rd Impression.)

4. ARGENTINA. By W. A. Hirst. With an Introduction by Martin Hume, a Map, and 64 Illustrations. (4th Impression.)

5. BRAZIL. By Pierre Denis. With a Historical Chapter by Bernard Miall, a Map, and 36 Illustrations. (2nd Impression.)

6. URUGUAY. By W. H. Koebel. With a Map and 55 Illustrations.

7. GUIANA: British, French, and Dutch. By James Rodway. With a Map and 36 Illustrations.

8. VENEZUELA. By Leonard V. Dalton, B.Sc. (Lond.), F.G.S., F.R.G.S. With a Map and 36 Illustrations. (2nd Impression.)

9. LATIN AMERICA: Its Rise and Progress. By F. Garcia Calderon. With a Preface by Raymond Poincaré, President of France, a Map, and 34 Illustrations. (2nd Impression.)

10. COLOMBIA. By Phanor James Eder, A.B., LL.B. With 2 Maps and 40 Illustrations. (2nd Impression.)

11. ECUADOR. By C. Reginald Enock, F.R.G.S.

12. BOLIVIA. By Paul Walle. With 62 Illustrations and 4 Maps.

13. PARAGUAY. By W. H. Koebel.

14. CENTRAL AMERICA. By W. H. Koebel.

"The output of the books upon Latin America has in recent years been very large, a proof doubtless of the increasing interest that is felt in the subject. Of these the South American Series edited by Mr. Martin Hume is the most noteworthy."—Times.

"Mr. Unwin is doing good service to commercial men and investors by the production of his 'South American Series.'"—Saturday Review.

"Those who wish to gain some idea of the march of progress in these countries cannot do better than study the admirable 'South American Series.'"—Chamber of Commerce Journal.

Vol. II. Frontispiece.

ITS ROMANCE, REALITY AND FUTURE

BY

C. R. ENOCK, C.E., F.R.G.S.

AUTHOR OF "THE ANDES AND THE AMAZON," "PERU," "MEXICO," "ECUADOR," ETC.

WITH 26 ILLUSTRATIONS AND A MAP

VOL. II

T. FISHER UNWIN LTD

LONDON: ADELPHI TERRACE

First published in 1920

(All rights reserved)

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| IX. | THE LANDS OF THE SPANISH MAIN: COLOMBIA AND VENEZUELA | 11 |

| X. | THE LANDS OF THE SPANISH MAIN: VENEZUELA AND GUIANA | 32 |

| XI. | THE AMAZON VALLEY: IN COLOMBIA, VENEZUELA, ECUADOR, BOLIVIA, PERU AND BRAZIL | 74 |

| XII. | BRAZIL | 111 |

| XIII. | THE RIVER PLATE AND THE PAMPAS: ARGENTINA, URUGUAY AND PARAGUAY | 158 |

| XIV. | THE RIVER PLATE AND THE PAMPAS: ARGENTINA, URUGUAY AND PARAGUAY | 202 |

| XV. | TRADE AND FINANCE | 236 |

| XVI. | TO-DAY AND TO-MORROW | 254 |

| INDEX | 303 | |

| BRONZE STATUE OF BOLÍVAR IN THE PLAZA, CARÁCAS, VENEZUELA | Frontispiece |

| TO FACE PAGE | |

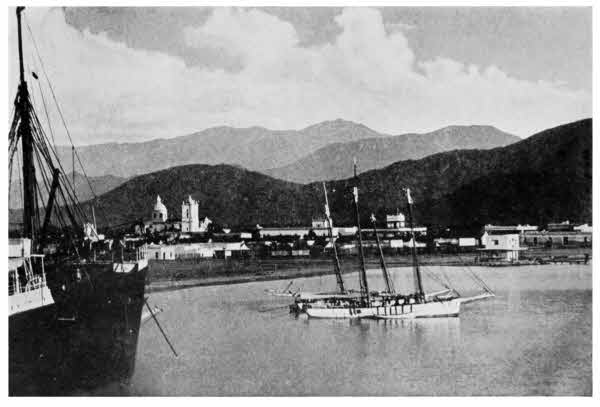

| A SEAPORT ON THE AMERICAN MEDITERRANEAN, SANTA MARTA, COLOMBIA | 14 |

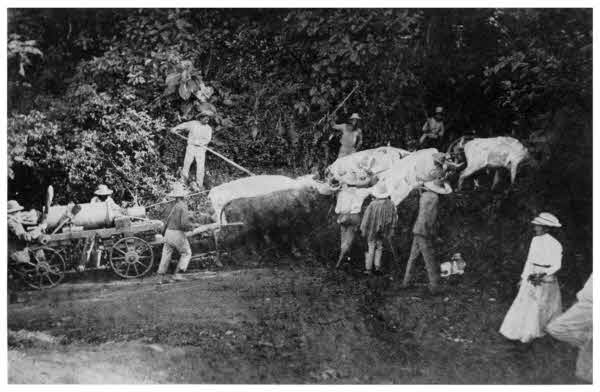

| TRANSPORTING MACHINERY IN THE COLOMBIAN ANDES | 22 |

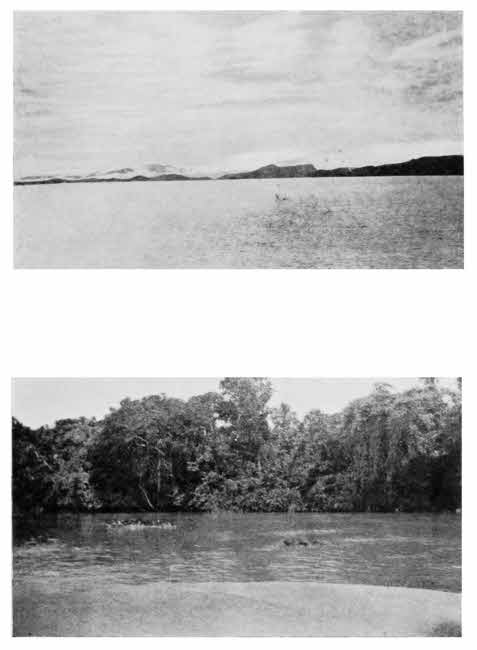

| THE MAINLAND FROM TRINIDAD, AND VIEW IN THE DELTA OF THE ORINOCO | 34 |

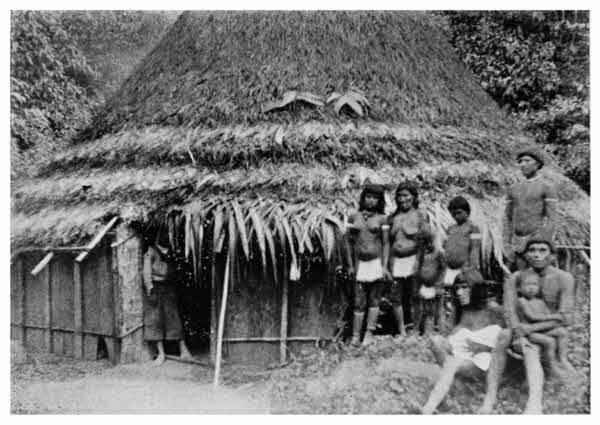

| INDIANS AT HOME, GUIANA | 52 |

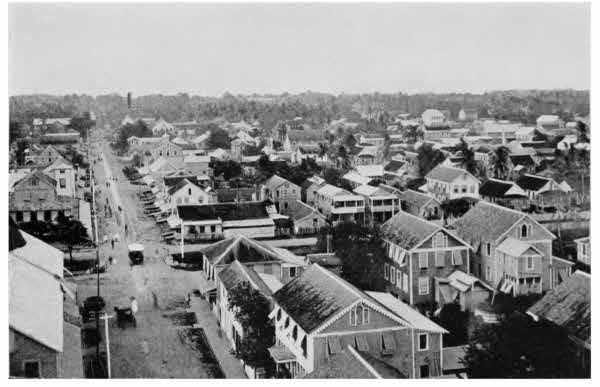

| GEORGETOWN, BRITISH GUIANA | 64 |

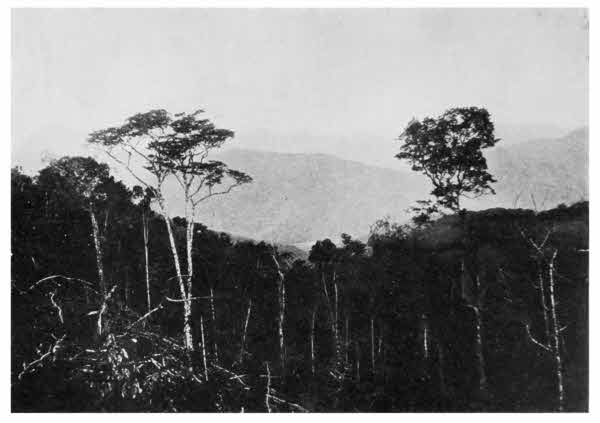

| IN THE PERUVIAN MONTAÑA | 78 |

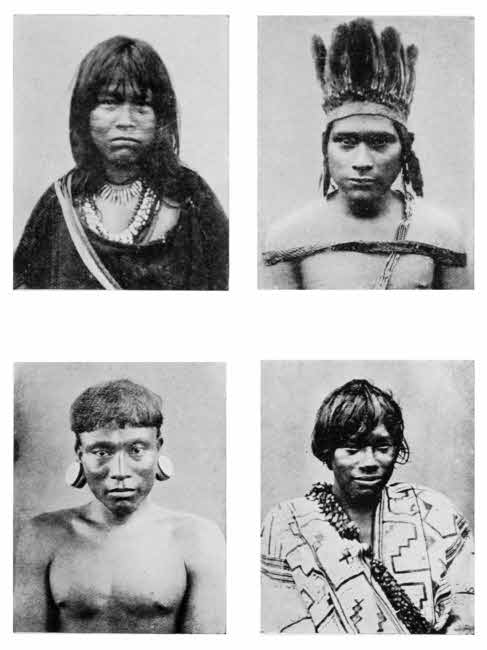

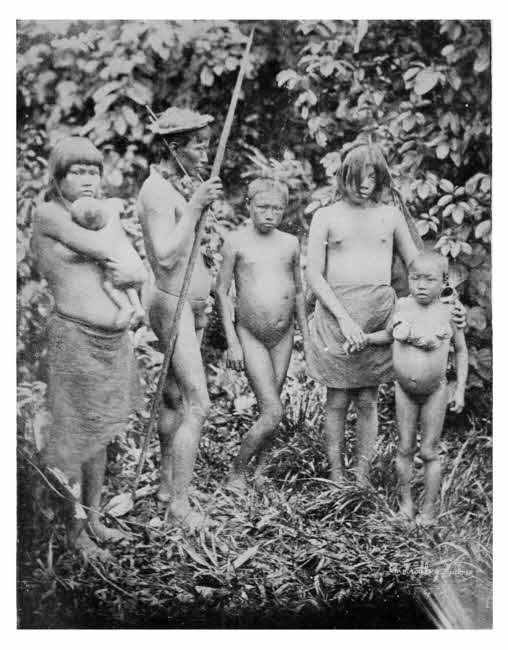

| UNCIVILIZED FOREST INDIANS OF THE PERUVIAN AMAZON | 90 |

| INDIANS OF THE NAPO, PERUVIAN-AMAZON REGION | 96 |

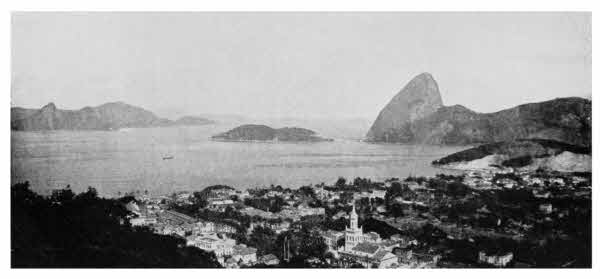

| THE BAY OF RIO DE JANEIRO | 112 |

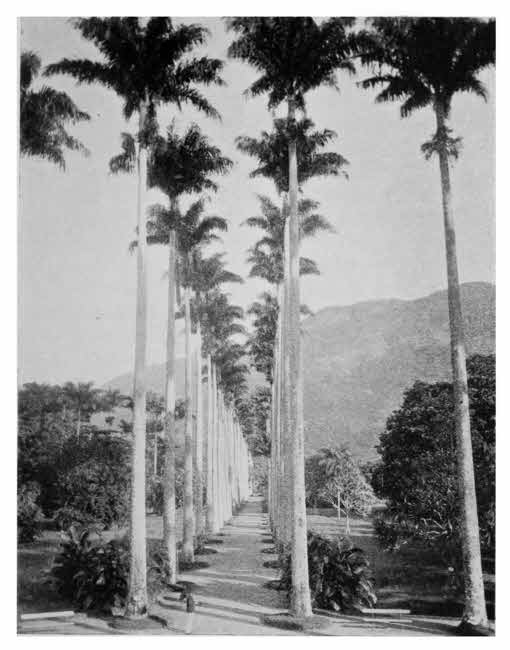

| PALM AVENUE, RIO DE JANEIRO | 128 |

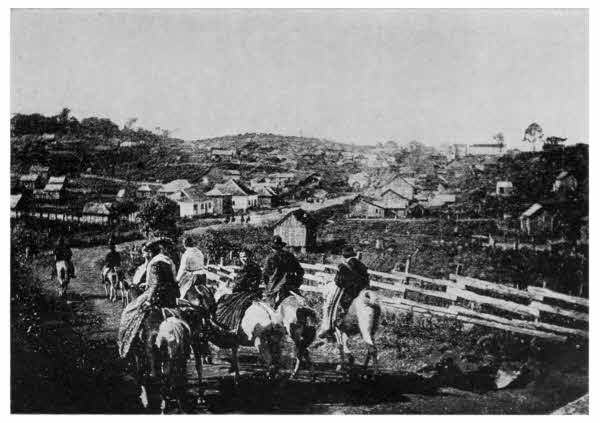

| A COLONY, RIO GRANDE | 132 |

| A VIEW IN SAO PAULO | 140 |

| COFFEE HARVEST, BRAZIL | 150 |

| BUENOS AYRES | 160 |

| MAR DEL PLATA | 166 |

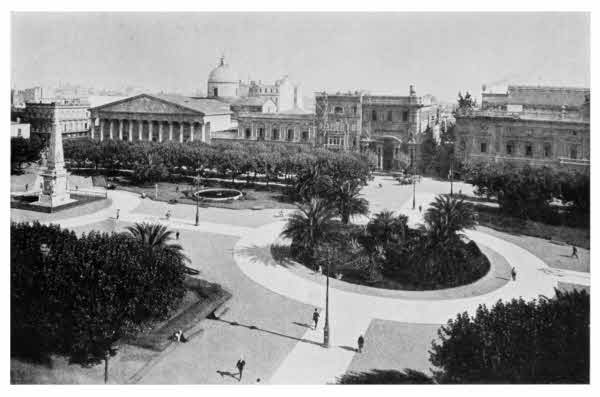

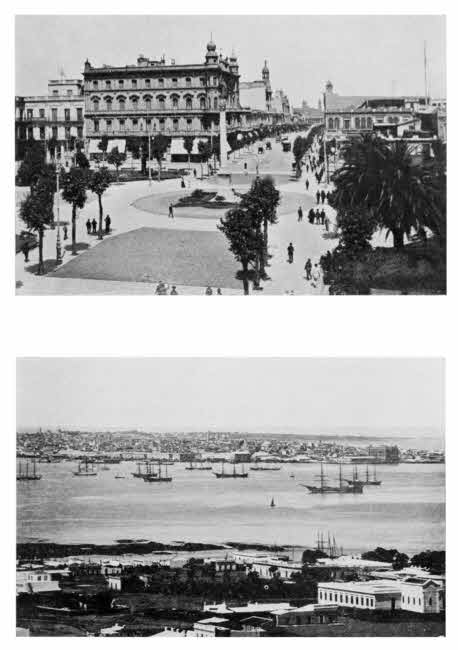

| MONTEVIDEO: THE PLAZA | 178[10] |

| MONTEVIDEO: THE HARBOUR | 178 |

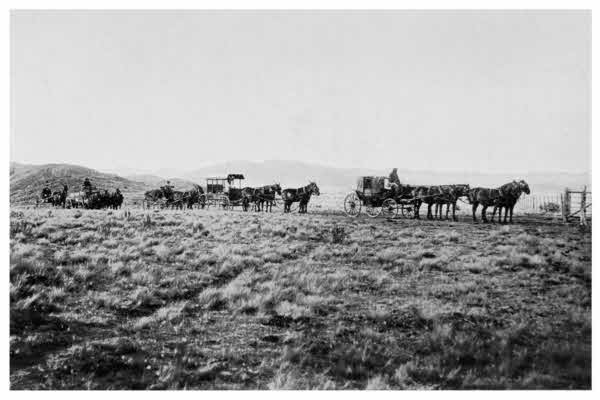

| THE PAMPAS, ARGENTINA | 204 |

| THE CITY OF CORDOBA, ARGENTINA | 206 |

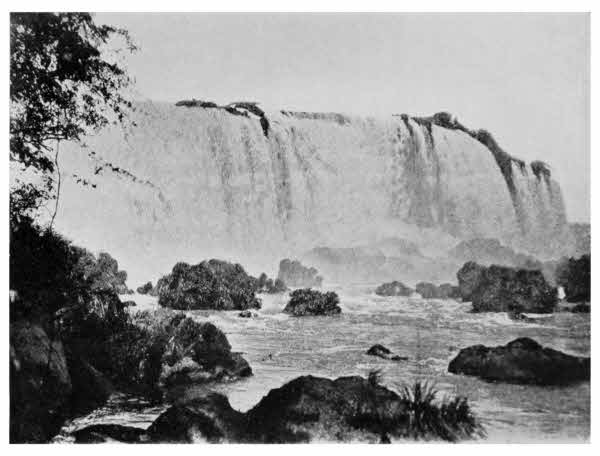

| IGUAZU FALLS | 210 |

| A CHACO FLOOD | 214 |

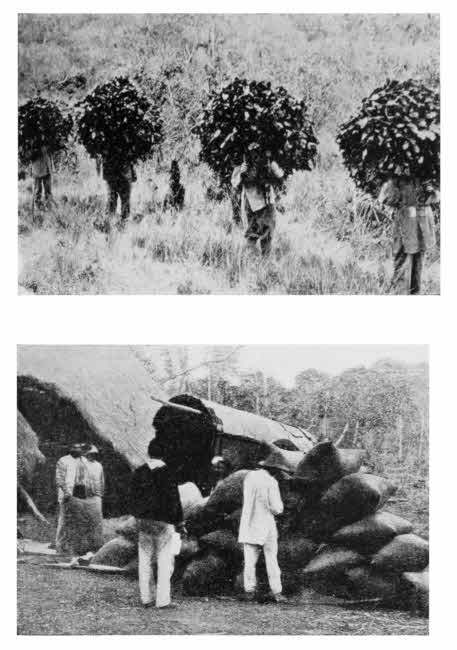

| BRINGING HOME YERBA | 220 |

| PACKING YERBA | 220 |

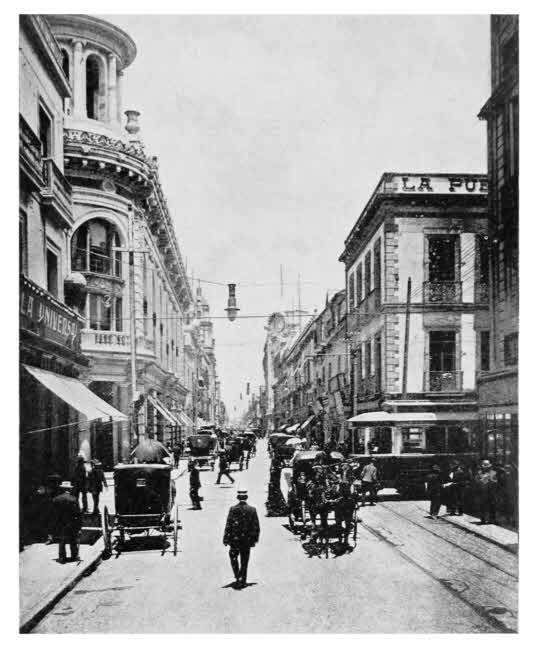

| STREET IN MEXICO CITY. CATHEDRAL IN DISTANCE | 264 |

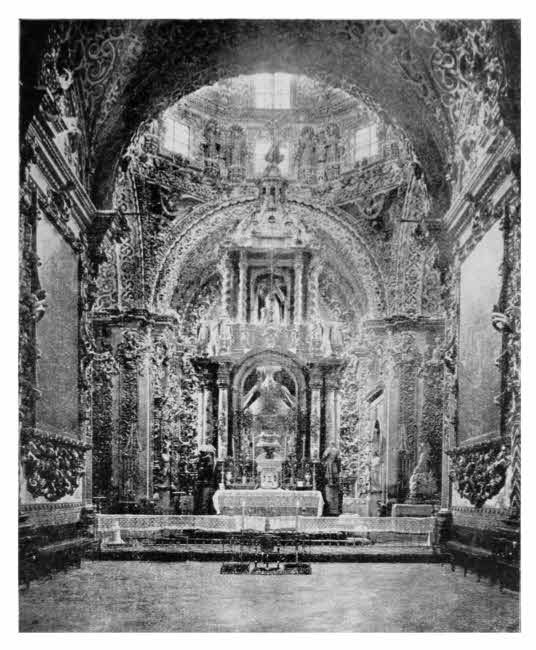

| CHAPEL OF THE ROSARIO, MEXICO | 266 |

SPANISH AMERICA

A sea-wall of solid masonry, a rampart upon whose flat top we may walk at will, presents itself to the winds and spray that blow in from the Gulf of Darien upon the ancient city of Cartagena, and the booming of the waves there, in times of storm, might be the echo of the guns of Drake, for this rampart was raised along the shore in those days when he and other famous sea rovers ranged the Spanish Main, over which Cartagena still looks out.

Cartagena was a rich city in those days, the outlet for the gold and silver and other seductive matters of New Granada, under the viceroys, and the buccaneers knew it well, this tempting bait of a treasure storehouse and haven of the Plate ships. This, then, was the reason for the massive sea-wall, one of the strongest and oldest of the Spanish fortifications of the New World, which Spain had monopolized and which the sea rovers disputed.

There is a certain Mediterranean aspect about[12] Cartagena, which was named by its founder, the Spaniard, Pedro de Heredia, in 1533, after the Spanish city of Carthage, founded by the Phœnicians of the famous Carthage of Africa. The steamer on which we have journeyed has crossed the American Mediterranean, as the Caribbean has been not altogether fancifully termed, for there is a certain analogy with the original, and passing the islands and entering the broad channel brings into view the ancient and picturesque town, with the finest harbour on the northern coast of the continent, a smooth, land-locked bay, with groups of feathery palms upon its shores.

Backed by the verdure-clad hills—whereon the better-class residents have their homes, thereby escaping the malarias of the littoral—the walls and towers of the town arise, and, entering, we are impressed by a certain old-world dignity and massiveness of the place, a one-time home of the viceroy and of the Inquisition. There are many memories of the past here of interest to the English traveller. Among these stands out the attempt of Admiral Vernon, in 1741, who with a large naval force and an army—under General Wentworth—arrived expecting an outpost of the place, which Drake had so easily held to ransom, to fall readily before him. The attempt was a failure, otherwise the British Empire might have been established upon this coast.

Colombia, like Mexico, has been a land of what might be termed vanished hopes and arrested development.[13] But the old land of New Granada, as Colombia was earlier termed, has not the weight of wasted opportunity and outraged fortune which now envelops the land of New Spain, which in our generation promised so much and fell from grace. Colombia, by a slower path, may yet reach a greater height than Mexico as an exponent of Spanish American culture.

But a century ago, at the time Colombia freed herself, in company with her neighbours, from the rule of Spain, her statesmen as well as her neighbours hailed her as a favoured land upon which fortune was to shine, which was to lead in industrial achievement, to redress the balance of the Old World, to offer liberty and opportunity to the settler, riches to the trader, to be a centre of art and thought. At that time, indeed, New Granada was the leading State in all the newly born constellation of Spanish America, and during her earlier republican period one of her orators, with that command of grandiloquent phrase with which the Spanish American statesman is endowed, spoke as follows:

"United, neither the empire of the Assyrians, the Medes or the Persians, the Macedonian or the Roman Empire can ever be compared with this colossal Republic!"

The speaker—Zea, the vice-president—was referring to the Republic of La Gran Colombia, formed, under Bolivar, of Venezuela, Colombia and Ecuador—a union which was soon disrupted and which neither geography nor human politics could[14] have done aught but tend to separate. The union, like that of Central America, fell asunder amid strife and bloodshed.

But let us take the road to Bogota, the beautiful and in many respects highly cultured capital of Colombia.

We do not, however, take the road, but the river, starting either from Cartagena by the short railway to Barranquilla, the seaport at the mouth of the Magdalena River, or direct from that port, and thence by the various interrupted stages of a journey that has become a synonym of varied travel to a South American capital.

Barranquilla is an important place—the principal commercial centre of the Republic. Here we embark upon a stern-wheel river steamer of the Mississippi type, flat-bottomed, not drawing more than three to five feet of water. The smaller boat, though less pretentious, may sometimes be the better on the long voyage upstream, and may pass the bigger and swifter craft if haply, as occurs at times, that craft be stranded on a shoal. For the river falls greatly in the dry season.

Vol. II. To face p. 14.

Journeying thus, we reach La Dorada, six hundred miles upstream, in about nine days, for there are many obstacles against time on the way, such as the current, the taking-in of fuel, the sand bars, which prohibit progress by night, slow discharge of merchandise and so forth. The heat may be stifling. A gauze mosquito bar or net is among the equipment of the prudent traveller, as is a cot or hammock, and rugs against the chill[15] and damp of the nights. Also food, for the commissariat on board often leaves much to be desired. In Colombia the traveller requires clothing both light and heavy, as indeed in almost all Spanish American countries. Quinine, moreover, must always be among his equipment.

At Puerto Berrio, five hundred miles up the river, a railway runs to the interesting city of Medellin, in the mountains, the second city in importance in Colombia.

There are, from La Dorada, various changes to be made before Bogota is reached. We must change to the railway that runs to—near—Honda, circumventing the rapids, a line about twenty miles long. Here we have a choice of routes and methods. We may proceed on mule-back through magnificent scenery and the refreshing atmosphere of the Andes, with tolerable inns, or we may take the steamer again to Giradot, on the Upper Magdalena, and then a further trajectory of eighty miles by rail. Seven changes are necessary in this journey from Cartagena to the capital—ocean-steamer to train, thence to river-steamer, from that to the train again, thence to river-steamer once more, thence to the train, and again to another train—doubtless a record of varied travel.

The remote and famous city of Santa Fé de Bogota, founded by Quesada in 1538, the old viceregal capital of New Granada, the "Athens of South America" as some of its admirers have termed it, stands pleasingly upon its Sabana, or upland plain—one of the largest cultivated mountain[16] plateaux in the world—at an elevation of 8,600 feet above sea-level, higher than the famous city of Mexico. It is in the heart of the Tropics, but four degrees north of the Equator, and its equable climate, a result of the offsetting of latitude by altitude, is in many respects delightful.

Here the typical Spanish American character is stamped on the city and reflected in the life of its people, where Parisian dress rubs shoulders with the blanketed Indian. Here the aristocracy of Colombia, implanted by Spain, centres. One street may be lined with the handsome residences of the correct and elegant upper class, folk perhaps educated in foreign universities, men of the world, passing by in silk hat and frock-coat—attire beloved of the wealthy here—or in motor-car or carriage, which whirls past the groups of half-starved, half-clothed (and perhaps half-drunken) Indian or poor Mestizo folk, whose homes are in the hovels of a neighbouring street and whose principal source of entertainment is the chicheria, or drinking-den, such as exists in profusion. And without desiring to institute undue comparisons—for wealth and misery go side by side in London or New York, or any city of Christendom—it may be pointed out that despite the claim of Bogota to be a centre of literary thought and high culture, little more perhaps than a tenth of the population of Colombia can read and write.

There are handsome plazas, with gardens and statuary, but few imposing public buildings, although a certain simplicity is pleasing here. The[17] streets generally are narrow, and the houses low, as a precaution against earthquake shocks. The Capitiolio, the building of the Legislature, is spacious and handsome. Upon a marble tablet, upon its façade, in letters of gold, is an inscription to the memory of the British Legion, the English and Irish who lent their aid to Colombia and Venezuela, under Bolivar, to secure independence from Spain a century or more ago.

The story of the British soldiers in this liberation is an interesting one.

"With insubordination and murmurings among his own generals, decreased troops and depleted treasure, and without the encouragement of decisive victories to make good these deficiencies, the outlook for Bolivar and for the cause in which he was fighting might well have disheartened him at this time. In March, however, Colonel Daniel O'Leary had arrived with the troops raised by Colonel Wilson in London, consisting largely of veterans of the Napoleonic wars. These tried soldiers, afterwards known as the British Legion, were destined to play an all-important part in the liberation of Venezuela, and Bolivar soon recognized their value, spending the time till December in distributing these new forces to the best advantage.

"Elections were arranged in the autumn, and on February 15, 1819, Congress was installed in Angostura. Bolivar took the British Constitution as his model, with the substitute of an elected[18] president for an hereditary king, and was himself proclaimed provisional holder of the office. The hereditary form of the Senate was, however, soon given up."[1]

Before the Conquest Bogota was the home of the Chibchas people—Tunja was their northern capital—the cultured folk of Colombia, who, although inferior to the Incas of Peru, had their well-built towns and a flourishing agriculture and local trade, their temples of no mean structure, with an advanced religion which venerated and adored the powers of Providence as represented by Nature; who worked gold and silver and ornaments of jewels beautifully and skilfully, such things as Quesada's Spaniards coveted—a culture which knew how to direct the Indian population, but which, alas! fell before the invaders as all other early American cultures fell.

To-day, as then, the high mountains look down upon the Sabana, and the rills of clear water descend therefrom. Still the beautiful Mesa de Herveo, the extinct volcano, displays like a great tablecloth from a giant table its gleaming mantle of perpetual snow, over 3,000 feet of white drapery. Still the emerald mines of Muzo yield their emeralds, and still the patient Indian cultivates the many foods and fruits which Nature has so bountifully lavished upon his fatherland.

Colombia, like Peru or Mexico, or Ecuador or other of the sisterhood of nations in our survey,[19] is a land of great contrasts, whether of Nature or man. The unhealthy lowlands of the coast give place to the delightful valleys of higher elevations, which in their turn merge into the bitter cold of the melancholy paramos, or upland passes, and tablelands of the Andes. Or the cultivated lands pass to savage forests, where roam tribes of natives who perhaps have never looked upon the face of the white man.

Every product of Nature in these climates is at hand or possible, and the precious minerals caused New Granada to be placed high on the roll of gold-producing colonies of the Indies. The coffee of the lowlands, the bananas, shipped so largely from the pretty port of Santa Marta, the cotton, the sugar and the cocoa, grown so far mainly for home consumption; the coconuts, the ivory-nuts—tagua, or coróza, for foreign use in button-making largely—the rice, the tobacco, the quinine, of which shipments have been considerable; the timber, such as cedar and mahogany; the cattle and hides, the gold, silver, platinum, copper, coal, emeralds, cinnabar, lead, the iron and petroleum—such are the chief products of this favoured land.

Many of the mines and railways are under British control, but in general trade German interests have been strong, and the German has identified himself, after his custom, with the domestic life of the Republic. A rich flora, including the beautiful orchids, is found here, as in the neighbouring State of Venezuela.

Two-fifths of Colombia is mountainous territory, the plateaux and spurs of the Andes, between which latter run the Magdalena and Cauca Rivers. The roads are mule-trails, such as bring again and again before us as we experience their discomforts the fact that Colombia, in common with all the Andine Republics, is still in the Middle Ages as far as means of rural transport are concerned. Yet the landscape is often of the most delightful, and the traveller, in the intervals of expending his breath in cursing the trails, will raise his eyes in admiration of the work of Nature here.

Especially is this the case when, in the dry season, travel is less onerous and when nothing can be more pleasing than the varying scenery. Here "dipping down into a delightful little valley, formed by a sparkling rivulet whose banks are edged with cane, bamboo and tropical trees, inter-wreathed with twining vines; there, circling a mountain-side and looking across at a vast amphitheatre where the striking vegetation, in wild profusion, is the gigantic wax-palm, that towers sometimes to a height of 100 feet; then, reaching the level of the oak and other trees of the temperate zone, or still higher at an altitude of 10,000 or 11,000 feet, the paramos, bare of all vegetation save low shrubs, which might be desolate were it not for the magnificent mountain scenery, with the occasional view of the glorious snow-peaks of the Central Cordillera.

"At times the road is poor: now and then, cut into the solid rock of the mountain-side, towering sheer hundreds of feet above you, while a precipice yawns threateningly on the other side, it may narrow down to a scant yard or two in width; it may, for a short distance, climb at an angle of almost forty-five degrees, with the roughest cobble paving for security against the mules slipping; or in a stretch of alluvial soil, the ruts worn by the constant tread of the animals in the same spot have worn deep narrow trenches, characteristic of Andean roads, against the sides of which one's knees will knock roughly if constant vigilance be not exercised; worse yet, these trenches will not be continuous, but will be interrupted by mounds over which the mules have continually stepped, sinking the road-bed deeper and deeper by the iterated stamping of their hoofs in the same hollow, till deep excavations are formed, which in the rainy season are pools filled with the most appalling mud. Such is a fair picture applicable to many a stretch of so-called road in Colombia.

"The 'hotel accommodations' on the way are poor, of course; one stops at the usual shanty and takes such fare as one can get, a sancocho or arepas, eked out with the foods prudentially brought along. It is in such passes as the Quindio, too, when one reaches the paramos, thousands of feet in altitude, and far above the clouds, that one experiences the rigorous cold of the Tropics. The temperature at night is nearly always below[22] forty degrees; occasionally it drops to freezing-point, and one feels it all the more after a sojourn in the hot lowlands. No amount of clothing then seems adequate. Travellers will remember the bitter cold nights they have passed in the paramos."[2]

This bitter atmosphere is experienced, let us remember, on or near the Equator. But we are led on to the beautiful Cauca Valley perhaps, whence, if we wish, we may continue on through the pretty town of Cali, and up over the tablelands of Popayan and Pasto, and, passing the frontier, so ride on to Quito, the capital of Ecuador—a journey which will leave us with sensations both painful and pleasurable.

Vol. II. To face p. 22.

"If you cannot withstand the petty discomforts of the trail for the sake of the ever-shifting panorama of snow-peaks, rugged mountains, cosy valleys, smiling woodlands, trim little valleys, then you are not worthy to be exhilarated by the sun-kissed winds of the Andes, or soothed by the languorous tropical moonlight of the lower lands, or to partake of the open-handed hospitality which will greet you.

"Such is the fame of the Cauca Valley that it was long known throughout Colombia simply as the valley, and that is now its legal name. It is the valley par excellence. The name is used to designate especially that stretch, about 15 to[23] 25 miles wide and 150 miles long, where the Cauca River has formed a gently sloping plain, at an altitude of 3,000 to 3,500 feet above sea-level, between the Central and the Western Cordilleras. A little north of Cartago and a little south of La Bolsa, the two ranges hem it in. The Cauca is one of the real garden spots of the world. No pen can describe the beauty of the broad smiling valley, as seen from favourable points on either range, with its broad green pastures, yellow fields of sugar-cane, dark woodlands, its towns nestling at the foothills, the Cauca River in the midst, silvered by the reflected sun, and looking across the lomas of the rapidly ascending foothills, with cameo-cut country houses, topped by the dense forests of the upper reaches of the mountains, rising to majestic heights. From some places in the western range will be seen the snow-clad Huila in icy contrast to the blazing sun shining on the luxuriant tropic vegetation beneath.

"The best developed parts of the hot and temperate zones of Cundinamarca are along the Magdalena Valley and the routes of the Girardot Railway, the road to Cambao and the Honda trail. In the warmer zone there are good sugar plantations: in the temperate zone is grown the coffee so favourably known in the markets of the world under the name of Bogota: it attains its perfection at an altitude of about 5,000 feet, and nowhere else in Colombia has such careful attention been given to its cultivation. The Sabana itself, by which name the plateau of Bogota is known, is[24] all taken up with farms and towns—there is scarcely a foot of undeveloped land. The climate is admirably adapted to the European-blooded animals, and the gentleman-farmer of Bogota takes great pride in his stock. The finest cattle in Colombia, a great many of imported Durham and Hereford stock, and excellent horses of English and Norman descent are bred here. This is the only section in Colombia, too, where dairying on any extensive scale is carried on, and where the general level of agriculture has risen above the primitive. The lands not devoted to pasture are utilized chiefly for wheat, barley and potatoes.

"To offset bad water, the food supply is excellent, and of wonderful variety. That is one of the beauties of the climate of the Sabana. One gets all northern fruits and flowers, blooming the year round, and vegetables as well as quite a few of the tropical ones. It is an interesting sight to see tropical palms growing side by side with handsome northern trees, like oaks and firs. Some of the Sabana roads are lined with blackberries, and one gets delicious little wild strawberries; apples, pears and peaches are grown, though usually of a poor quality, not properly cultivated. Even oranges can grow on the Sabana, and from the nearby hot country they send up all manner of tropical fruits and vegetables. Then there is no dearth of good cooks: the epicure can enjoy private dinners and public banquets equal to any in the world. The one lady who reads this book will be interested to know that[25] the servant problem is reduced to a minimum in Bogota; good domestics are plentiful and cheap—five to ten dollars a month is high pay. In the houses of the well-to-do the servants are well treated and lead happy lives; they have ample quarters of their own, centring around their own patio; and enough of the old patriarchal regime survives to make them really a part of the family."[3]

Descending from the mountainous part of the country, we reach, to the east, that portion of Colombia situated upon the affluents of the Orinoco, a region which we may more readily consider in our description of that great river, lying mainly in the adjoining Republic of Venezuela. Here stretch the llanos, or plains, and the forests which are the home of the wilder tribes, for Colombia has various grades of civilization among her folk, of which the last are these aboriginals, and the middle the patient Christianized Indians, who constitute the bulk of the working classes. These last have the characteristics, with small differences, of the Indian of the Cordillera in general, of whom I have elsewhere ventured upon some study.

In Colombia, although in some respects the Republic is pervaded by a truly democratic spirit as between class and class, power and privilege, land and education are in the hands of a small upper class. This condition does not make for[26] social progress, and in the future may seriously jeopardize the position of that class. Wisdom here, as elsewhere in Spanish America, would advise a broader outlook. Political misrule in the past has been rampant, although revolutions of late years have been infrequent.

There are innumerable matters in Colombia which the observant traveller will find of the utmost interest, but upon which we cannot dwell here. Our way lies back to the Spanish Main, whence we take steamer along the coast to the seaports of Venezuela.

Colombia is in a unique geographical position upon the South American Continent, in that it is the only State with an Atlantic and Pacific coast; added to which is the hydrographic condition which gives the country an outlet also to the fluvial system of the Amazon, by means of the great affluents the Yapura and the Negro, as also the Putumayo—if that stream is to be regarded in Colombian territory, for the region is on the debatable ground claimed by three countries, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru.

Indeed, this portion of South America, one of the wildest parts of the earth's surface, is of great hydrographic interest, and looking at the map, we see how these navigable streams bend north, east and south, with the peculiar link of the Casiquiare "Canal" or river, uniting the fluvial systems of the Orinoco and the Amazon. (It is—but on a vaster scale—as if a natural waterway existed between the Thames and the Severn, or[27] the Mississippi and the St. Lawrence.) This "Canal" lies but 150 miles from the Equator, a few miles from the border of Colombia, in Venezuela. Beyond, to the north-east, is Guiana, the land of Raleigh's El Dorado. Doubtless this region, in the future—far-off it may be—will become of much importance, and what is now savage woodland and danger-haunted waterways may some day be teeming with life and activity.

The conditions as regards navigability are, of course, relative in many instances here. Again, the region is not necessarily altogether an uninhabited one, for the rubber-stations have been increasing rapidly of late years.

A somewhat forbidding coast presents itself as our steamer, casting anchor, comes to rest in the waters of La Guayra, the principal seaport of Venezuela.

Here a bold rocky wall, apparently arising sheer from the sea, a granite escarpment more than a mile high, cuts off all view of the interior, and, reflecting the heat of the tropic sun, makes of the small and somewhat unprepossessing town at its base one of the hottest seaports on the face of the globe, as it was formerly one of the most dangerous from the exposure of its roadstead.

But, as if in some natural compensation, there lies beyond this rocky, maritime wall one of the most beautiful capital cities of South America—Caracas, reached by yonder railway, strung along the face of the precipice, and affording from the[28] train a magnificent panorama of the seaport and the blue Caribbean.

La Guayra, ranged like an amphitheatre around the indentations in the precipice in which it lies, with its tiers of ill-paved streets, has nevertheless some good business houses, and the Republic expended a million pounds sterling upon its harbour works, executed and controlled by a British company.

Looking seaward from its quay walls, we may recall the doings of the old buccaneers of the Spanish Main, and of other filibusters, who from time to time have sacked the place since its founding in the sixteenth century. Upon these quays are filled bags of cocoa and coffee, and mountains of hides, brought down from the interior, and other products from plain and field and forest of the hinterland, for La Guayra monopolizes, for State reasons, much of the trade that might more naturally find outlet through other seaports.

The little railway which bears us up and beyond to Caracas winds, to gain elevation and passage, for twenty-four miles, in order to cover a distance in an air-line between the port and the capital of about six. We find ourselves set down in what enthusiastic descriptions of this particular zone love to term a region of perpetual spring; and indeed, at its elevation of 3,000 feet, the city is alike free from the sweltering heat of the coast and from the cold of the higher mountainous districts beyond.

A handsome plaza confronts us, with an equestrian[29] statue of Bolivar. The plaza is mosaic-paved, electrically lighted, shaded by trees and, in the evening and on Sunday, the military bands entertain the people after the customary Spanish American method. Some showy public buildings, and a museum with some famous paintings are here; there are pleasing suburbs, luxurious gardens and well laid-out streets, and this high capital takes not unjustifiable pride to itself for its beauty and artistic environment and atmosphere—conditions which deserve a wider fame.

When we leave the Venezuelan capital and travel over the wide territory of the Republic, we find it is one of the most sparsely populated of the Spanish American nations. Conditions in internal development and social life are very much like those of Colombia, with highlands and lowlands, river and forest, cultivated plain and smiling valley, malarial districts and dreary uplands. We find the rudest Indian villages and the most pleasing towns: the most ignorant and backward Indian folk, the more docile and industrious Christianized labouring class, and the highly educated, sensitive and oligarchical upper class.

Again, we find the same variety of climate, products and the gifts of Nature in general. We see great plantations of coffee, especially in that fertile region of Maracaibo, which Colombia in part enjoys, and which gives its name to the superior berry there produced for export. We see broad estates, in their thousands, devoted to the production of the cacao, or chocolate, and similar[30] areas over which waves the succulent and vivid green sugar-cane, whereon sugar is produced often by old-fashioned methods. These products yield returns so excellent that the growing of cotton, on the vast lands suitable thereto, are in large degree neglected, and must be regarded as an asset for the future, whenever local labour may become better organized or more plentiful.

Agriculture in this varied Republic, as in its neighbour, Colombia, has been kept backward by the same lack of labour, largely a punishment for the decimation of the labouring folk in the civil and other wars that have so often laid waste both man and land.

Maracaibo, lake and district, of which we have made mention, is in some respects a curious region. Let us look at the map. We remark a great indent on the coast of the Spanish Main. It is the Gulf of Venezuela, continuing far inland to what is termed Lake Maracaibo. The gulf is partly closed by the curious Goajira Peninsula.

From the appearance of the dwellings of the Indian on this lake-shore, the name of Venezuela, or "Little Venice," was given to the mainland here; the lake-dwellings are built on piles driven into the water. When the first Spaniards visited the coast, under Alonzo de Ojeada—on board with him was Amerigo Vespucci, the Florentine who gave his name to America—they were struck by the curious appearance of the Indian settlements, and from so accidental a circumstance was[31] the region baptized. The same type of dwelling still characterizes the lake, and were it not for the busy and important town of Maracaibo, the traveller might almost fancy himself back in the sixteenth century, coasting with the early explorers.

Indeed, as far as the Indians of the peninsula are concerned, we might still be in these early times, for these sturdy descendants of the Caribs, whom the Spaniards came to dread, have maintained their independence to this day, and although they trade with the white folk, resist all attempts at governmental control. This is a curious circumstance upon the coast, which was the first part of South America to be discovered, although it might be conceivable in the far interior—especially in view of the proximity of the busy and populous city on the lake, a port of greater importance than La Guayra in some respects, full of modern life and trade. Maracaibo was at one time one of the principal educational centres of South America. Unfortunately the bar at the mouth of the harbour unfits the place for the entry of large vessels.

In this district lie the important petroleum fields, which have been made the seat of recent enterprise for the production of that coveted oil of commerce.

If, as we have said, the approach to the Republic of Venezuela at La Guayra seems forbidding and inaccessible, it must not be inferred that this is an inevitable characteristic of the coast. The Caribbean Hills are splendid in their aspect from the sea. They are forbidding in their grandeur. The mighty ramparts rise almost sheer from the ocean for thousands of feet, with cloud-veils flung across them at times, and if, from the steamer's deck, we may wonder how access to the hinterland can be gained, we shall find that Nature has furnished her passes, and some of the early English adventurers of the Spanish Main scaled these, as we may read in the stirring pages of Hakluyt.[4] Personally, I retain strong impressions of these cool-appearing, towering ramparts of Nature seen whilst sweltering in the tropic heat on shipboard.

Moreover, the great spurs of the Andes die[33] out into the sea as we go east, and so Nature has broken down the rampart, giving vent to her marvellous hydrographic forces, which here triumph over the orographic, in the Gulf of Paria and the delta of the Orinoco, clothed with the densest of tropical vegetation, the home of wild beast and wild man, as shortly we shall observe.

There are further memories of British activity in regard to Venezuelan seaports, more modern, less picturesque than those we have already remarked. For, in the year 1903, the loans and arrears upon interest, the defaulted payments and disputed interpretations of contracts, in railway construction and other matters, and alleged arbitrary behaviour on the part of Venezuelan Government officials, came to a head, with the result that Great Britain, Germany and Italy sent a combined fleet to blockade the seaports, and an enforced settlement of the creditors' claims was brought about.

However, these unfortunate incidents are of the past. Venezuela has shown a desire for more cordial relations with the outside world. Lately she sent a representative to London with the purpose of inaugurating closer commercial relations with Britain.[5]

We have now to explore the great river of Venezuela, the famous Orinoco.

The Orinoco, which pours its huge volume of water into the Atlantic on the northern shore of[34] the continent, through a vast delta of over thirty mouths, a volume derived from over four hundred tributaries which descend from the spurs of the Andes or from the wild and mysterious forests of Guiana, flows through what might be one of the richest valleys of the earth's surface, and doubtless in the future may so become. But, like the valley of the Amazon, its resources are comparatively little utilized at present. Devastating floods, malarious forests, ferocious crocodiles are some of the elements the traveller encounters on the higher waters of this great stream, notwithstanding that Columbus wrote to his Spanish sovereign that he had "found one of the rivers flowing from the Earthly Paradise."

Unfortunately it may be said that the Spaniard and his descendants have wrought destruction rather than benefit here, and the population of the valley is less now than it was four centuries ago.

We may ascend the Orinoco, in the stern-wheel steamers which ply thereon, for about four hundred miles to Ciudad Bolivar, which town forms the chief and indeed almost the only trade centre, and in the rainy season, when the river is high, which is generally from June to November, by smaller craft up the lengthy affluents. Such are the Apure, the Meta, the Arauca and the Guaviare, many hundreds of miles in length, rising far away to the west amid the Cordillera, the cold eastern slopes of whose lofty summits condense and pour down torrents of water into an extraordinary network of rivers which flow across the[35] plains of Colombia and Venezuela, flooding enormous areas of land in their passage to the main stream. Boats and barges may reach the Andes, whose beautiful landscape forms the water-parting of this remarkable fluvial system.

Vol. II. To face p. 34.

In the dry season snags and sandbanks render navigation almost impossible on many of these tributaries, and in some cases in the remote districts the hordes of savages who dwell on the banks add to the dangers of the voyager. There are miles of rapids on certain of the waterways, and great cataracts, whilst the forest comes down to the water's edge, forming an impenetrable screen of tropical vegetation, in which the traveller who strays from his way is lost. This jungle is flooded in the rainy season, the waters driving back all animal life to the higher ground.

From the east comes the great Ventuari affluent, with its unexplored head-waters in Guiana.

The Orinoco River is of much interest, whether to the traveller or the hydrographer, and doubtless some day its potentialities will be more greatly utilized. In some respects this fluvial system would lend itself to the improvements of the engineer, and might perform for the region which it waters services such as the Nile renders for Egypt, instead of being, as it is, largely a destructive agent. The general slope of the river is comparatively slight, and thus canalization and consequent improvement in navigation might be carried out. Nearly a thousand miles from the mouth the waters of one of the principal affluents[36] are little above sea-level, but the rise and fall of the flood is sometimes as much as fifty feet, and confluences two miles wide in the dry season are increased three or four times during the rains.

One of the most interesting features of these rivers, as already remarked, is found in the singular natural canal connecting the Orinoco with the Amazon—the waterway of the Casiquiare Canal,[6] which cuts across the water-parting of the two hydrographic systems. Here the adventurous canoe voyager may descend from the Orinoco and reach the Rio Negro, falling into the Amazon near Manaos.

The endless waterways of the upper reaches of the Orinoco share often that silent, deserted character which we shall remark upon the Amazon tributaries, and which indeed, is common to tropical streams often. Bird and animal life seems all to have concealed itself. Even the loathly alligator is not to be seen, nor the turtle, nor other creature of the waters. Occasionally, however, a scarlet ibis appears to break the monotony, or an eagle or heron. For mile upon mile, league upon league, there may be no opening in the green wall of the dismal forest, until, suddenly, as we pass, the wall gives way, a small clearing is seen, with perhaps a Carib Indian hut, dilapidated and solitary, whose miserable occupant, hastily entering his canoe, shoots out from the[37] bank with some meagre objects of sale or barter in the form of provisions or other.

Such, however, is not always the nature of these rivers. The scene changes: there are sandy shores and bayous, beautiful forest flowers and gorgeous insect life, the chatter of the monkeys and the forms of the characteristic tropical fauna. Rippling streams flow from inviting woodland glades untrodden by man, and high cascades send their showers of sparkling drops amid the foliage and over the fortress-like rocks around. Wafted along by sail or paddle, guided by the expert Indian boatmen, the craft weathers all dangers, and the passenger sees pass before him a panorama of the wilds whose impression will always remain upon his mind. Thus the charm of exploration never fails, and, borne upon the bosom of some half-unknown stream, the traveller's cup of adventure may on the Orinoco be filled to the brim.

For many hundreds of miles these western tributaries of the Orinoco flow through the llanos, as the plains of this part of South America—in Colombia and Venezuela—are termed, whose characteristic flatness we shall remark from the deck of the vessel. A sea of grass stretches away to the horizon on every side, giving place in some districts to forest.

The level plains, lying generally about four hundred feet above the sea, were once the home of enormous herds of cattle and horses and of a hardy, intrepid race of folk known as the llaneros,[38] men who kept and tended the cattle and were expert in horsemanship and woodcraft. These folk flourished best in the Colonial period. They formed some of the best fighting material in South America, and made their mark in the War of Independence, when, under Bolivar, the Spanish yoke was thrown off. Again, civil war, revolution and hardships and losses consequent thereon seriously reduced their numbers, and to-day both they and their herds have almost disappeared.

The great plains which were the scene of these former activities might, under better auspices, become an important source of food supply, both for home and foreign needs. They could again support vast herds of cattle on their grassy campos, irrigated by the overflow of the Orinoco. This overflow, it is true, causes extensive lagoons to form, known locally as esteros or cienagas, but these dry up in great part after the floods, which have meantime refreshed the soil and herbage.

"The great green or brown plain of the Llanos is often beautified by small golden, white and pink flowers, and sedges and irises make up much of the small vegetation. Here and there the beautiful 'royal' palm, with its banded stem and graceful crown, the moriche, or one of the other kinds, forms clumps to break the monotony, and along the small streams are patches of chaparro bushes, cashew-nuts, locusts and so forth. The banks of the rivers often support denser groves of ceibas, crotons, guamos, etc.; the last-named bears a pod[39] covered with short, velvety hair, within which, around the beans (about the size of our broad beans), is a cool, juicy, very refreshing pulp, not unlike that of the young cocoa-pod. Along the banks of the streams in front of the trees are masses of reeds and semi-aquatic grasses, which effectually conceal the higher vegetation from a traveller in a canoe at water-level."[7]

Much stress has been laid upon the possible economic value of the llanos by some writers, whilst others regard these possibilities as exaggerated.[8] Their area is calculated at 100,000 square miles. They are neither prairies nor desert. During a large part of the year they are subject to heavy rainfall and become swamped, followed by a drought so intense that the streams dry up and the parched grass affords no pasture for stock. There is a total lack of roads, and the rivers are unbridged, and the region is far from the ocean. The trade wind blows fiercely across them.

The view over these vast plains as the traveller's eyes suddenly rest upon them as he descends the Andes is very striking, and has been described by various observers, among them Humboldt.

In the wet season, when the river overflows, the cattle are driven back to higher ground. When the waters retire alligators and water snakes bury themselves in the mud to pass the dry season.

In this connexion stories are told of travellers and others who, having camped for the night in some hut or chosen spot, are suddenly awakened by the upheaval of the ground beneath them and the emergence of some dreadful monster therefrom. A certain traveller's experience in the night was that of being awakened by the barking of his dogs, the noise of which had roused a huge alligator, which heaved up the floor of the hut, attacked the dogs and then made off.[9]

As for the old type llanero, half Spanish, half Indian, the wild, brave, restless, devil-may-care cowboy, a Cossack of the Colombian Steppes and a boastful Tartarin full of poetic fire rolled into one, is rapidly disappearing. Vanished is the poetry and romance of his life, if it ever really existed outside of his remarkable cantos, wherein heroic exploits as soldier, as hunter and as gallant lover are recounted with a superb hyperbole. He seems to have tamed down completely, in spite of the solitary, open-air life, and in spite of the continuance of a certain element of danger, battling with the elements. Encounters with jaguars, reptiles, savage Indians are, however, the rarest of episodes in the life of even the most daring and exposed llanero.[10]

A "picturesque" character of original llanero stamp was the notorious President Castro of Venezuela, who defied the whole world at one time, and almost succeeded in bringing about a conflict[41] between England and the United States over the Guiana-Venezuela boundary.

The wild tribes of Venezuela, and part of British Guiana, are typified in those inhabiting the delta of the Orinoco. They have preserved their racial character in marked degree here, and have been regarded as an offshoot of the Caribs.

"They are dark copper in colour, well set up, and strong, though not as a rule tall, and with low foreheads, long and fine black hair, and the usual high cheek-bones and wide nostrils of the South American 'Indians.' Where they have not come into contact with civilization they are particularly shy and reticent, but they soon lose this character, and some are said to show considerable aptitude as workmen.

"Living as they do mainly in the delta, their houses are of necessity near water, and are raised from the ground as a protection against floods, being sometimes, it is said, even placed on platforms in trees. The roof is supported in the middle by two vertical posts and a ridge pole, and is composed of palm-leaves, supported at the corners by stakes. The sides of this simple hut consist of light palm-leaf curtains, and the floor is of palm-planks. The hammocks are slung on the ridge pole, and the bows and arrows of the occupants fixed in the roof, while their household furniture, consisting of home-made earthenware pots, calabashes of various sizes, etc., lie promiscuously about the floor. Some of the[42] Warraus are nomadic, and live in canoes, but the majority are grouped in villages of these huts, with captains responsible to the Venezuelan local government authorities.

"The staple diet of these people is manioc and sago, with chicha (a mixture of manioc meal and water). For clothing they dispense with everything in their homes, except the buja or guayuco, a tiny apron of palm-fibre or ordinary cloth, held in position by a belt of palm-fibre or hair. That worn by women is triangular, and often ornamented with feathers or pearls. Among the whites the men always wear a long strip of blue cloth, one end of which passes round the waist, the other over the shoulder, hanging down in front; the women have a kind of long sleeveless gown. For ornament they wear necklaces of pearls, or more frequently of red, blue and white beads, and tight bracelets and bangles of hair or curagua (palm-fibre); some pierce ears, nose and lower lips for the insertion of pieces of reed, feathers or berries on fête days. The characteristic dull red paint on their bodies is intended to act as a preventive against mosquitoes, and it is made by boiling the powdered bark and wood of a creeper in turtle or alligator fat. All hair is removed from the body by the simple but painful process of pulling each one out with a split reed.

"Marriage, as is usual among savage races, takes place at a very early age, the husband being often only fourteen, the wife ten or twelve years of age. Polygamy is common, but not universal;[43] where a chief or rich man has several wives, the first, or the earliest to become a mother, takes charge of the establishment during the absence of the owner on his hunting or fishing expeditions. The girls are sometimes betrothed at the age of five or six years, living in the house of the future husband from that time on.

"At birth the mother is left in a separate house alone, where all food that she may need is placed for her, though she remains unvisited by any of her companions throughout the day; meanwhile the father remains in his hammock for several days, apparently owing to a belief that some evil may befall the child; there he receives the congratulations of the villagers, who bring him presents of the best game caught on their expeditions. This male child-bed, or couvade, is common to many of the Indian tribes.

"The dead are mourned with elaborate ceremony—shouting, weeping and slow, monotonous music; the nearest relatives of the defunct cut their hair. The body is placed in leaves and tied up in the hammock used by the owner during life, and then placed in a hollow tree-trunk or in his canoe. This rude coffin is then generally placed on a small support, consisting of bamboo trestles, and so left in the deserted house of the dead man."[11]

The wild animal life of this part of South America has always been of interest, whether to[44] the scientist or the general reader. It is varied, as it is in Mexico and elsewhere in Spanish America, by the natural topographical and climatic divisions of tierra caliente, tierra templada and tierra fria, or hot, temperate and cold lands respectively.

The various kinds of monkeys include the spider-monkeys, the squirrel-monkeys, the marmosets, the vampires, the jaguar and puma—the former of which has been credited with living in the high branches of the trees in flood-times, to the perturbation of the monkeys, upon whose home it intrudes, chasing them to the tree-tops. In the Andes the peculiar "Speckled bear" has its abode. The manati is a native of the Orinoco, and the sloth of its forests, as also the "Ant-bear" and armadillo.

These creatures may not always be readily seen by the passing traveller, but the birds are more present, although, as elsewhere in the Tropics, their plumage is more noteworthy than their song.

"Beautifully coloured jays, the peculiar cassiques, with their hanging nests, starlings, and the many violet, scarlet and other tanagers, with some very pretty members of the finch tribe, are all fairly abundant in Venezuela. Greenlets, some of the allied waxwings, and thrushes of various kinds, with the equally familiar wrens, are particularly abundant, nor does the cosmopolitan swallow absent himself from this part of the world. The numerous family of the American flycatchers has[45] fifty representatives in Venezuela, and the allied ant-birds constitute one of the exceptions to the rule, in possessing a pleasant warbling note. The chatterers include some of the most notable birds of Venezuela, and we may specially notice the strange-looking umbrella-bird which extends into the Amazon territory, known from its note as the fife-bird; the variegated bell-bird, which makes a noise like the ringing of a bell; the gay manikins, whose colours include blue, crimson, orange and yellow, mingled with sober blacks, browns and greens; the nearly allied cock-of-the-rock is one of the most beautiful birds of Guayana, orange-red being the principal colour in its plumage, while its helmet-like crest adds to its grandeur; the hen is a uniform reddish-brown. The wood-hewers are more of interest from their habits than the beauty of their plumage.

"The beautiful green jacamars, the puff-birds, and the bright-coloured woodpeckers are found all over Venezuela in the forests, but their relatives the toucans are among the most peculiar of the feathered tribe. With their enormous beaks and gaudy plumage they are easily recognized when seen, and can make a terrible din if a number of them collected together are disturbed, the individual cry being short and unmelodious. Several cuckoos are found in Venezuela, some having more or less dull plumage and being rare, while others with brighter feathers are gregarious. With the trogons, however, we come to the near relatives of the beautiful quezal, all medium-sized birds, with[46] the characteristic metallic blue or green back and yellow or red breasts. The tiny, though equally beautiful, humming-birds are common sights in the forest, but a sharp eye is needed to detect them in their rapid flight through the dim light; some of the Venezuelan forms are large, however, notably the king humming-bird of Guayana; and the crested coquettes, though smaller, are still large enough to make their golden-green plumage conspicuous. The birds which perhaps most force themselves, not by sight but by sound, upon the notice of travellers are the night-jars; the 'who are you?' is as well known in Trinidad as in Venezuela. The great wood night-jar of Guayana has a very peculiar mournful cry, particularly uncanny when heard in the moonlight. The king-fisher-like motmots have one representative in Venezuela, but the other member of the group, which includes all the preceding birds, constitute a family by itself. This is the oil-bird, or guacharo, famous from Humboldt's description of the cave of Caripe in which they were first found. The young birds are covered with thick masses of yellow fat, for which they are killed in large numbers by the local peasantry. They live in caves wherever they are found, and only come out to feed at dusk.

"Other birds which are sure to be observed even by the least ornithological traveller are the parrots and macaws, which fly in flocks from tree to tree of the forest, uttering their discordant cries. The macaws have blue and red or yellow plumage,[47] but the parrots and parraquets are all wholly or mainly of a green hue. The several owls are naturally seldom seen, and, in the author's experience, rarely heard.

"There are no less than thirty-two species of falcons or eagles known from Venezuela, and of these many are particularly handsome, such as the swallow-tailed kite and the harpy eagle of Guayana. Their loathsome carrion-eating cousins, the vultures, have four representatives.

"In the rivers and caños of the lowlands there are abundant water-birds, and the identified species include a darter, two pelicans, several herons or garzas, the indiscriminate slaughter of which in the breeding season for egret plumes has been one of the disgraces of Venezuela, as well as storks and ibises. Among the most beautiful birds of these districts are the rosy, white or scarlet flamingoes, huge flocks of which are sometimes seen rising from the water's edge at the approach of a boat or canoe. There are also seven Venezuelan species of duck.

"The various pigeons and doves possess no very notable characteristics, and one or two of the American quails are found in the Andes. Other game-birds include the fine-crested curassows of Guayana, the nearly allied guans and the pheasant-like hoatzin. There are several rails, and the finfeet are represented. The sun bittern is very common on the Orinoco. There are members of the following groups: the trumpeters (tamed in Brazil to protect poultry), plovers, terns, petrels,[48] grebes, and, lastly, seven species of the flightless tinamous.

"Descending lower in the scale, we come to the animals which are, or used to be, most often associated in the mind with the forests of South America. The snakes are very numerous, but only a minority are poisonous. Of the latter, the beautiful but deadly coral-snake is not very common, but a rattlesnake and the formidable 'bushmaster' are often seen. Of the non-poisonous variety the water-loving boas and tigres or anacondas are mainly confined to the delta and the banks of the Guayana rivers. The cazadora (one of the colubers) and the Brazilian wood-snake or sipo, with its beautiful coloration, are common; the blind or velvet snake is often found in the enclosures of dwellings.

"One of the lizards, the amphisbæna, is known in the country as the double-headed snake, and is popularly supposed to be poisonous, but there are many species of the pretty and more typical forms, especially in the dry regions, while the edible iguana is common in the forests. There are eleven species of crocodiles, of which the caiman infests all the larger rivers and caños. The Chelonidæ include only two land tortoises, but there are several turtles in the seas and rivers, and representatives of this family from the Gulf of Paria often figure on the menus of City companies.

"There are some six genera of frogs and toads to represent the Amphibians, and the evening croaking of the various species of the former on[49] the Llanos is very characteristic of those regions; one, in particular, emits a sound like a human shout, and a number of them give the impression of a crowd at a football match.

"Fish abound in rivers, lakes and seas, but, considering their number, remarkably little is known about them. Some are regarded as poisonous, and others are certainly dangerous, such as the small but ferocious caribe of the Llano rivers, which is particularly feared by bathers, as an attack from a shoal results in numbers of severe, often fatal, wounds. The temblador, or electric eel, is very abundant in the western Llanos, and is as dangerous in its way as the caribe.

"The insects are too numerous for more than casual reference, but it may be noted that the mosquito of the Spaniards is a small and very annoying sandfly; the mosquito, as we know it, is, and always has been, called zancudo de noche by the Spanish-speaking inhabitants of Venezuela. The gorgeous butterflies and the emerald lights of the fireflies are in a measure a compensation for the discomforts caused by their relatives, but of the less attractive forms, the most interesting are the hunting ants, which swarm through houses at times devouring all refuse, and the parasol ants, which make with the leaves they carry hot-beds, as it were, for the fungus upon which they feed.

"One of the most unpleasant of the lower forms of life in the forests is the araña mono, or big spider of Guayana, which sometimes measures more than six inches across; it is found in the remote[50] parts of the forest, and its bites cause severe fever. The better-known tarantula, though less dangerous, can inflict severe bites. The extremely poisonous scorpions, and the garrapatas, or ticks, must be seen or felt to be appreciated.

"We may leave the lower forms of life to more technical works, but the amusing 'calling-crab' deserves special mention. With his one enormous paw of pincers the male, if disturbed, will sit upon the mud or sand and apparently challenge all the world to 'come on' in a most amusing fashion."[12]

The wild people and the wild life of northern South America remind us again that the first discovered part of the continent is in some respects still the least known and most backward. The "streams flowing from the Earthly Paradise" of Columbus still traverse an Elysium for the adventurous traveller.

The coast of the Spanish Main trends now eastwards to the possession of Britain, in the Guayanas, and the beautiful Island of Trinidad, which we shall now enter upon.

Columbus, on his voyage in 1496, approaching South America, beheld three peaks rising from a beautiful island clothed with verdure. Uniting the pious custom of his time with his impression of the topography of the new land, he called the island "Trinidad," or the Trinity. Spain held it. Sir Walter Raleigh burned its capital, and finally it fell to Britain at the beginning of the nineteenth[51] century. To-day, this land off this wild coast, under the flag of Britain, is a revelation to the traveller, who—British or other—may have forgotten its existence. Its capital, Port of Spain, is one of the most pleasing towns in the West Indies, with two cathedrals, shaded streets, tramways, government institutions and public buildings, libraries, shops, a beautiful botanical garden and other evidences of a very modern civilization and activity. The soil is rich, the climate good, the hurricanes that from time to time devastate the West Indies do not visit it. It lies almost in the mouth of the river Orinoco. Venezuela claims it as hers. I well recollect the aspect of this foothold of Britain after the wilds of South America. But its modernity does not detract from the interest of the more ancient Spanish American communities.

British Guiana, whose coast we soon approach, and its neighbours, Dutch and French Guiana, are ranged in sequence along the Atlantic front for seven hundred miles, and present topographical conditions curiously alike.

Guiana, as a geographical term, is that district lying between the water-parting of the Orinoco and the Amazon and the coast; and is almost a topographical entity, embodying part of Venezuela. It is, in a sense, an island, by reason of the union of the Orinoco and Amazon fluvial systems by the Casiquiare.

Students of Anglo-American relations will recollect that the controversy over the boundary line[52] between British and Venezuelan territory here became the subject of contention—and almost of war—between Great Britain and the United States in 1895, by reason of the work of the wild President Castro and the unwarranted behaviour of President Cleveland of the United States—behaviour which was greatly resented by English people in South America and which has not yet been forgotten. Happily arbitration was entered upon—Britain practically being awarded what she had justly claimed.

British Guiana is one of the neglected outposts of the British Empire, the only foothold of England on the mainland of South America, a place of considerable interest, beauty and utility, but about which the good folk of Great Britain know and perhaps care little.

The British public cannot be expected to be well acquainted with all the outlying parts of the immense empire which fortune or providence has delivered over to them, but, through their statesmen, they could, if they were so minded, bring about a much more constructive and energetic policy than that which the inaccessible and old-fashioned Colonial Office and Crown Colony officials consider does duty for government and development.

The population of this land is a handful of folk of about the size of a second-rate English town, notwithstanding that the extent of the country is equal to the whole of Great Britain. Its rich littoral is watered by large rivers, rising in a little-known[53] interior. Sugar is produced, but might be produced in quantities to satisfy the British house-wife did British folk know anything about the subject. There are enormous timber resources and valuable minerals.

Vol. II. To face p. 52.

But in such development comes the cry for "labour." It is the first cry of all tropical possessions. Where is labour to come from? The remedy generally proposed is that of bringing in coloured labour from other parts of the empire, coolies and others. This policy has some fatal defects. Among these the practice of bringing in hordes of coloured men without their women or families is one of the most unwise. It is unnatural to condemn these folk to live without their female partners, and if persisted in will, sooner or later, bring serious evils upon the community that practises it. The existing labour should be more carefully fostered, and if labour be imported it should be as far as possible in the form of permanent settlers, with their wives and families, the condition of whose life and surroundings should be intelligently mapped out beforehand.[13]

Guiana brings back sad memories of Sir Walter Raleigh, he who by reason of his antagonism to Spain was a popular hero, and around whose figure much romance has centred.

Partly with the object of recouping his fortune, Raleigh sailed, in 1595, to Guiana, a voyage of exploration and conquest, with the main object of finding that El Dorado which was so strong an obsession of Elizabethan times, imagined to be hidden somewhere amid the Cordillera or forests of Spanish America. His book, recounting the incidents of this voyage, The Discoverie of Guiana, which he published upon his return home, is one of the most thrilling adventurous narratives of the period, although it has been said that it contains much that was romance rather than fact: and incredulity marked its reception. On his second expedition, after Elizabeth's death—an expedition which was perhaps one of the saddest of forlorn hopes, whereby Raleigh hoped, trusting perhaps to a chapter of accidents, to escape from the dreadful position of disfavour and threatened execution into which he had fallen in the reign of James I—he reached Trinidad and sailed up the Orinoco, fell sick of a fever and suffered many[55] disasters in the endeavour to carry out his undertaking to find a vast gold mine upon territory not belonging to Spain. Should he fail, or trespass upon Spanish territory, he was to be executed as a pirate, a fate which practically befell him, though he was executed under his old sentence of conspiracy.

The illustrious Raleigh—whose name some writers love to belittle—"took a pipe of tobacco a little before he went to the scaffold," for the habit of smoking tobacco—that beautiful gift of the Spanish American Indian to the Old World—had become rooted among the Elizabethan courtiers.

But to return to Guiana. The topography of this part of South America is full of interest and variety, as are the history and customs of its people, aboriginal and other, although much of the past is marked by dreadful happenings. Wars, the deeds of buccaneers, rebellions of negroes, massacre of the whites, deaths from fevers and so forth stand out from its pages.

It is a magnificent country, with grand rivers, cascades and the most wonderful mountains and scenery, which it is difficult to surpass in any part of South America. And here the traveller and the naturalist may revel in the works of Nature.

Guiana was the first part of the New World to be explored by adventurers other than the Spaniard and the Portuguese, and to this day it stands out as foreign to the rest of Spanish[56] America. The English, the French, the Dutch fought between themselves for its territory and its colonizing and trading stations. The English sought an El Dorado, the Dutchman thought of its tobacco—which the Spaniards would not permit him to obtain from their colonies—the Frenchman took part possibly out of national pride, thinking he ought not to be left out in the partition, but his work seems to have been of a disastrous nature ever since he set foot there. The Pilgrim Fathers, before they "moored their bark on a wild New England coast," had dreams of settling here, where the warm climate and tropic possibilities seemed to hold out greater allurements than the cold coasts of the more northern continent. When Surinam, or Dutch Guiana, was exchanged for the New Netherlands and New Amsterdam—to-day New York—few Dutchmen dissented, and some English protested.

"Like the valley of the Amazon, to which system it may be considered an offshoot, it is a land of forest and stream. The coast is generally an alluvial flat, often below high-water mark, fringed with courida (Avicennia nitida) on the seashore, and mangrove (Rhizophora manglier) on the banks of the tidal rivers. Where it is not empoldered it is subject to the wash of the sea in front and the rising of the swamp water behind. In fact, it is a flooded country, as the name, from wina or Guina (water) seems to imply.

"The lowest land is the delta of the Orinoco,[57] where the rising of the river often covers the whole. Coming to the north-west of British Guiana, we have a number of channels (itabos) forming natural waterways through swamps, navigable for canoes and small vessels. A similar series of natural canals is found in Dutch Guiana. From the Orinoco to Cayenne this alluvium is rarely above high-water mark, and is subject to great changes from currents, the only protection being the natural palisade of courida, with its fascine-like roots. On the coast of Cayenne, however, the land rises, and there are rocky islands; here the swamps come at some distance behind the shore, and between ridges and banks of sand.

"Behind this low land comes the old beach of some former age—reefs of white quartz sand, the stunted vegetation of which can only exist because the rainfall is heavy and almost continuous. This is the fringe of the great forest region which extends over the greater part of the country. Here the land rises and becomes hilly, and the rivers are obstructed by a more or less continuous series of rocks, which form rapids and prevent them running dry when the floods recede. Behind these, to the south, the hills gradually rise to mountains of 5,000 feet, and in the case of a peculiar group of sandstone castellated rocks, of which Roraima is the highest, to 8,000 feet.

"The numerous rivers bring down vegetable matter in solution, clay and fine sand suspended and great masses of floating trees and grasses.[58] These form islands in the larger estuaries and bars at the mouths of most of the rivers; they also tinge the ocean for about fifty miles beyond the coast from green to a dirty yellow. Wind and wave break down the shore in one place and extend it in another, giving a great deal of trouble to the plantations by tearing away the dams which protect their cultivation. Every large river has its islands, which begin with sand-banks, and by means of the courida and mangrove become ultimately habitable. In the Essequebo there are several of a large extent, on which formerly were many sugar plantations, one of which remains in Wakenaam. The Corentyne and Marowyne have also fair-sized islands, but none of these has ever been settled. Off the coast of Cayenne the rocky Iles du Salut and Connetable are quite exceptional, for the coast is elsewhere a low mud-flat, sloping very gradually, and quite shallow.

"The longest river is the Essequebo, which rises in the extreme south, and like most of the larger streams, flows almost due north. It is about 600 miles in length; the Corentyne is nearly as long, and the Marowyne and Oyapok are probably about the same length. Other rivers that would be considered of great importance in Europe are seen at intervals of a few miles all along the coast. The Demerara, on which the capital of British Guiana is situated, is about the size of the Thames, and 250 miles long, and the Surinam, on the left bank of which is Paramaribo, 300. All are blocked by rapids at various distances[59] from 50 to about 100 miles inland, up to which they are navigable for small vessels, but beyond, only for properly constructed boats that can be drawn through the falls or over portages.

"The smaller rivers, called creeks, whether they fall into the sea or into the larger streams, are very numerous; over a thousand have Indian names. Many of them are of a fair size, and the majority have dark water of the colour of weak coffee, whence the name Rio Negro has been given to several South American rivers. These take their rise in the pegass swamps, so common everywhere, and are tinged by the dead leaves of the dense growth of sedges, which prevent these bodies of water from appearing like lakes. There are, however, a few deeper swamps, where a lake-like expanse is seen in the centre, but no real lakes appear to exist anywhere. The creeks are often connected with each other by channels, called itabos, or, by the Venezuelans, canos, through which it is possible to pass for long distances without going out to sea. During the rainy season these channels are easily passable, and light canoes can be pushed through from the head of one creek to that of another, the result being that large tracts of country are easily passed. In this way the Rio Negro and Amazon can be reached from the Essequebo in one direction and the Orinoco in another, the watersheds being ill-defined from there being no long mountain ranges.

"The higher hills and mountains are not grouped in any order. The group called the Pakaraima[60] are the most important from their position on the boundary between British Guiana, Venezuela and Brazil, and also from the neighbourhood of Roraima giving rise to streams which feed the Orinoco, Amazon and Essequebo. This peculiar clump of red sandstone rocks forms the most interesting natural object in Guiana. Roraima is the principal, but there are others, named Kukenaam, Iwaikarima, Waiakapiapu, etc., almost equally curious and striking. All have the appearance of great stone castles, standing high above the slopes, which are covered with rare and beautiful plants, some of which are unknown elsewhere. The main characteristics of this group are due to weathering, the result being grotesque forms that stand boldly forth, together with fairy dells, waterfalls decorated with most delicate ferns and mosses and grand clumps of orchids and other flowering plants."[14]

It is not to be supposed that British Guiana has been neglected by its modern administration. A great deal has been done in draining, in reconstructing the villages, in fostering agriculture, in organizing the natives, in providing against malaria and disease by scientific methods, such as at Panama had been found so beneficial. The treatment of immigrant labour is almost paternal in some respects. Surinam is also progressing, stimulated by the example of Demerara. Cayenne, the[61] French possession, suffers still from being a penal settlement.

The life of the coloured folk, who so largely predominate among the population, offers many problems, whose solutions will doubtless work themselves out. The people of Guiana are possibly more varied than those of any other community in the world, with representations of every race—the European and Indo-European, the African negro, the Chinese, folk from Java and Annam, together with its own native races, and the white American, with many mixed breeds.

In the views of the writer already quoted—

"Among the other points of interest there is the impress of the three nationalities upon the negro, which are very conspicuous in the women. The French negress is unlike her sister in Surinam, and she differs also from the English type in Demerara. Again, they all stand apart from the real African and the bush negro, illustrating the possibility of the perpetuation of acquired characters and the manner in which tribal differences have been developed. 'The French,' said an old writer, 'are a civil, quick and active sort of people, given to talking, especially those of the female sex'; the Dutch have a more heavy look and wear their clothes loose and baggy, cleanliness being more conspicuous than a good fit; the English (including specially the Barbardian) are decidedly careless and slovenly, and inclined to ape the latest fashion. A Frenchman speaks of the Demerara negress as[62] dressing up in her mistress's old gowns and wanting a style of her own; we have seen a cook going to market in an old silk dress once trimmed with lace, now smudged with soot and reeking with grease. They all have a love for finery but no taste in colour; here and there, however, a girl with a pure white dress and embroidered head-kerchief pleases the eye and proves that dress is of some importance in our estimate of these people.

"The negro man has no peculiarity in his clothes; he simply follows the European. His working dress is generally the dirty and ragged remains of what we may call his Sunday suit. He may be clean otherwise, but his covering gives us the contrary impression. There is a character about the Demerara creole, but he is not so English as the Barbadian, who is 'neither Carib nor creole, but true Barbadian born.' Loyalty to the Mother Country as well as to his own island is very conspicuous; he has followed the white man in this as well as in his language, which retains some of the obsolete words and phrases of the Stuart period, including the asseveration 'deed en fait' for 'in deed and in faith.' These national characteristics go to prove that the negro has been changed somewhat by environment, and this can be easily seen when he is compared with the African, who is represented here and there by a few of the old people who were rescued from slavers.

"The bush negro of Surinam, who ranges also through Cayenne and into Brazilian territory, is a[63] distinct type. Made up of a number of African tribes, and probably dominated by the Coromantee, the most independent of these, he has not been much affected by his short service under the Dutch. From a physical standpoint he is a fine fellow, muscular and brawny; a good boatman and warrior, he has held his own for two centuries. Having first gained his freedom by his strong arm, he fought to retain it; the result is a man that must be respected. Possibly he learnt something from the native Indian, but he has never been very friendly, for the aborigines do not like the negro. In Demerara, and to a less extent in Surinam, Indians were formerly employed to hunt runaway slaves, and this accounts for the ill-feeling.