Vol. XV OCTOBER, 1953 No. 6

Devoted to a better understanding of living things and fine surroundings in which we live

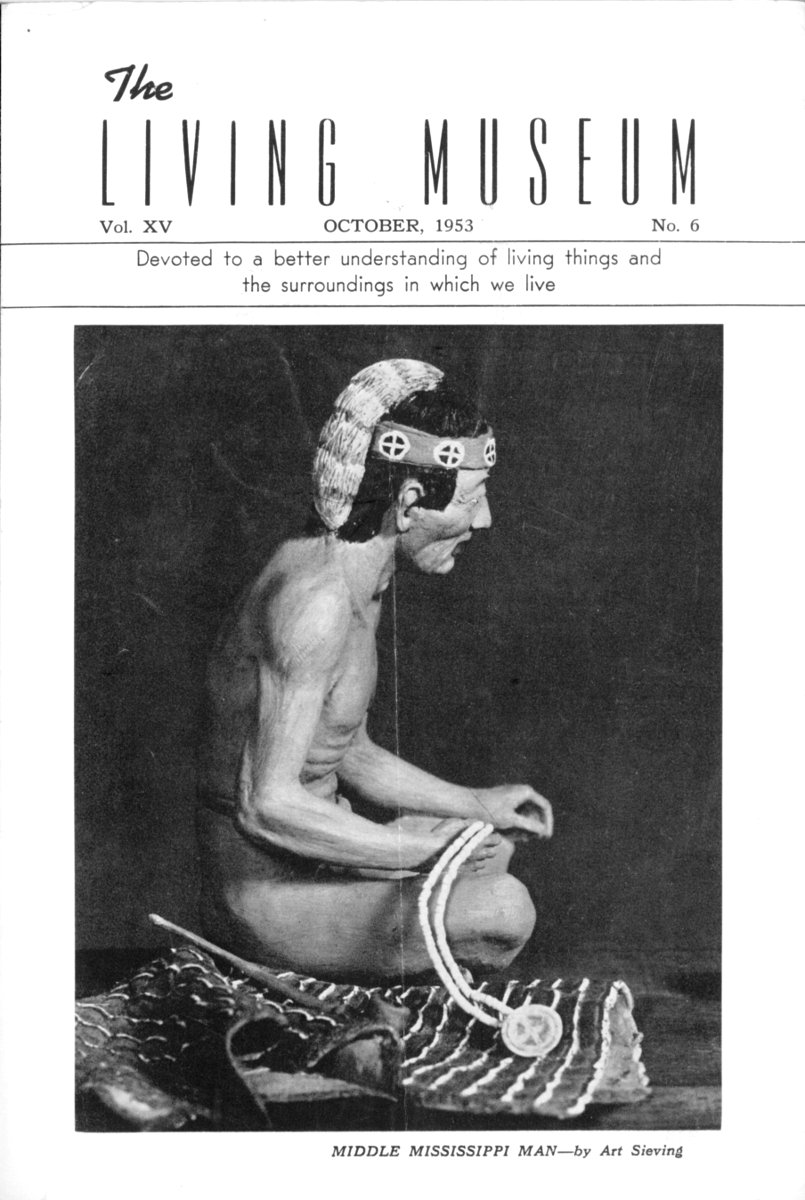

MIDDLE MISSISSIPPI MAN—by Art Sieving

Fifth Floor of the Centennial Building

Springfield, Illinois, State Capitol Group

ALWAYS FREE

Hours: Daily, 8:30 to 5. Sundays, 2 to 5 p. m.

Open every day except New Year’s Day, Fourth of July, Thanksgiving, and Christmas.

Dept. of Registration and Education

State of Illinois

Hon. Vera M. Binks, Director

Hon. William G. Stratton, Governor

Museum Board of Advisers

Hon. Vincent Y. Dallman, Chairman

Editor, Illinois State Register, Springfield

Hon. Robt. H. Becker, Outdoor Editor

Chicago Tribune, Chicago

M. M. Leighton, Ph.D., Chief

State Geological Survey, Urbana

Virginia S. Eifert, Editor

Thorne Deuel, Museum Director

(Printed by authority of the State of Illinois)

by Melvin Fowler, Curator of Anthropology

Museum visitors often wonder about the appearance of the prehistoric peoples of Illinois, but pictures of unearthed skeletons and pieces of aboriginal jewelry in museum cases do not wholly satisfy this interest. Anthropologists also are deeply concerned with ancient fashions of dress, yet remains or evidence of garments, cloth, and hair styles seldom come to light. True, anthropologists are able to determine something from beads, ear ornaments, and bracelets found with the dead in graves, and the relationship of these objects to the skeleton sometimes gives clues about the uses of the objects. For instance, it is a fair presumption that disc-shaped ornaments found near the ear region of a skull were ear pendants or decorations.

Occasionally, however, small clay figures are found which give considerable information on the dress and appearance of prehistoric Illinoisians. The purposes for which these statuettes were made by the Indians is not known; they often depict human beings, their clothing, and ornaments. Some are made of clay, others are carved of stone. In addition to statuettes, sculptures are sometimes added as decoration on pottery vessels and in modeling smoking pipes.

Recently a study has been made of the figures and objects made by Hopewellian peoples (who lived about 200 B.C. to 800 A.D.?) and much has been learned about their appearance.[1] Many figures and representations of human beings belonging to the Middle Mississippi Culture in Illinois (1200-1600 A.D.) have also been discovered. A study is being made of these figures at the present time to learn about Middle Mississippi costume, research which is necessary in preparing exhibits on Amerindians (American Indians) in the Museum and the Museumobile.

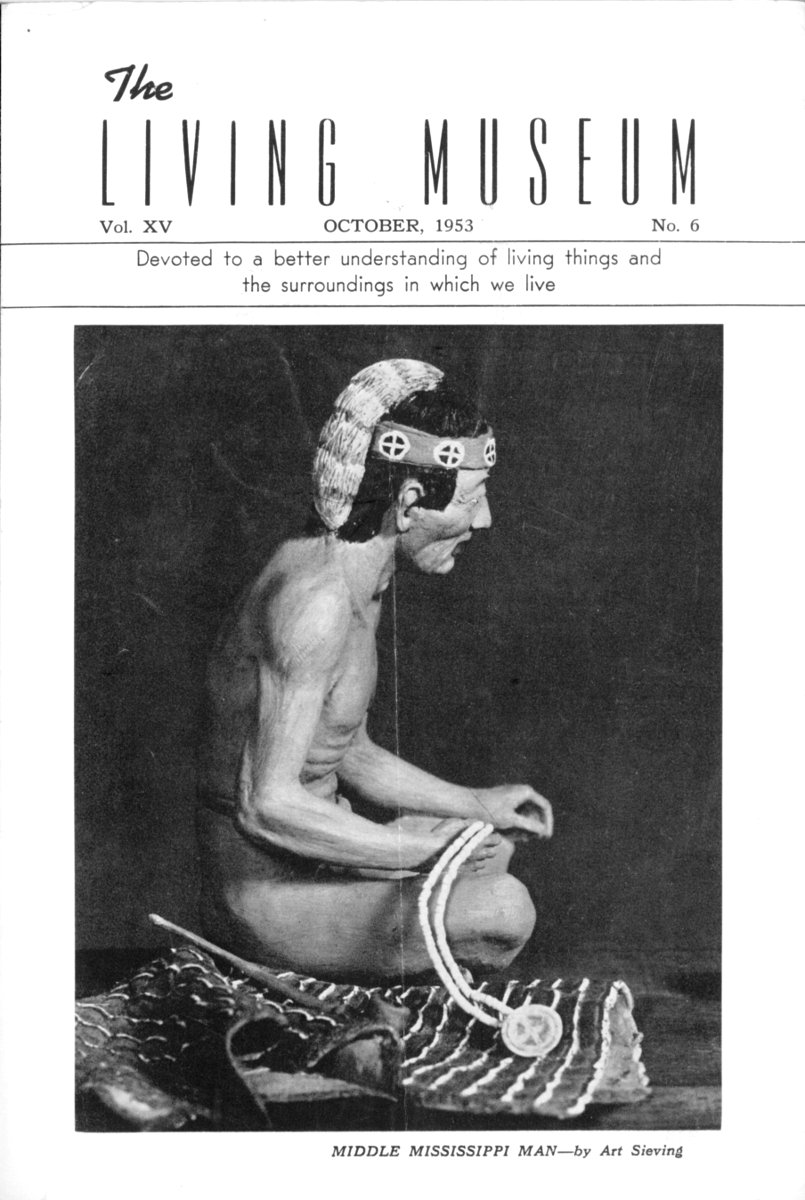

Already, much has been learned from the study of the figures available. For example, in studying a human figure in stone from the Kincaid Site near Brookport in Massac County, it was observed that the hair styling which was represented consisted of three main elements: a band of some sort around the head, hair bobbed over 419 the ears and cut at shoulder length behind, and an appendage or hair braid commencing on top of the head and trailing down behind. In turning to other Middle Mississippi figures represented in the Museum collection, several were found showing these same characteristics.

Original (right) and restored (left) Middle Mississippi Figurine

One of the most interesting figures of this type is the fragmentary top of a water bottle from Cahokia found by Mr. Gregory Perino of Belleville, Illinois. The opening of the bottle is made where the face of the figure would be. The hairdo is shown in detail, including all of the features mentioned above except that on this figure the hair is bobbed all around the head. The novel feature of this figure is the knot of hair shown in detail with the attached appendage indicating, in this case at least, that the pendant which trails down behind is not of hair, but something else.

When the early explorers came through the southeastern United States they found Middle Mississippi Indians still living there. Because the accounts of chroniclers of DeSoto’s expedition and the early French settlers of Louisiana are especially full, we are thus able to fill in our knowledge of the appearance of these Indians. From these sources, we find that headbands were commonly worn and the hair was often knotted on top of the head with “the tails of animals or their entire skins fastened to the hair....”[2]

Putting these fragments of evidence together, we have been able to construct a figure representing a Middle Mississippi man. The hair styling consists of the main features shown in the statuettes and figures. The head band is decorated with a circle and cross, a design found painted on Middle Mississippi pottery and engraved on pendants. A coon tail is attached to the hairknot on the crown of the head. In the man’s hand is a string of cut shell beads to which is attached a gorget (breast ornament) made of sea shell. At his side is a robe made of turkey feathers.

By these means we can at last answer the Museum visitor’s and the anthropologist’s questions, “How did they look?”—“How did Middle Mississippi people dress?”

Beginning October 10th, the Illinois State Museum Art Gallery under the direction of Frances S. Ridgely, Curator of Art, features an exhibition of textiles used in the restoration of pre-revolutionary homes. From among the many fabrics which Franco Scalamandré has reproduced for restoration of historic American houses, the Scalamandré Museum of Textiles has assembled this exhibition of woven materials of the 17th and 18th centuries.

Among the 17th century homes are those of the two noted Quakers, “Pennsbury Manor”, the country estate of William Penn, and the John Bowne House, Flushing, New York. The Hudson River Valley Dutch era is shown in “Philipse Castle”, North Tarrytown, New York. New England is represented by the modest cottage of Paul Revere, Boston, Massachusetts. The Howland House, Plymouth, Massachusetts, is reputed to be the only house still standing where once was heard the foot treads of the Pilgrims, and there is the famous Buckman Tavern, Lexington, Massachusetts, which was headquarters of the Minute Men, April 19, 1775, the night that ushered in the War of Independence.

As the colonies increased in population and wealth in the succeeding century, the homes became more pretentious in their furnishings. The textiles used in the 18th century homes were the beautiful silk damasks, brocatelles, lampases, brocades, velvets, and toiles.

Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia, is represented by the Governor’s Palace, the abode of the royal governors appointed by the King; the Wythe House, residence of George Wythe, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, and the Raleigh Tavern, the most famous hostelry of its time.

The town and plantation houses of the landed gentry include “Kenmore”, the home of George Washington’s only sister, Betty Washington Lewis, at Fredericksburg, Virginia; the Heyward-Washington House, Charleston, South Carolina; the Hammond-Harwood House, Annapolis, Maryland; the Ford Mansion, Morristown, New Jersey, Washington’s headquarters at the time Lafayette arrived to bring the glad tidings that France was sending an army to help the American cause. There are a number of others equally as famous. The owners of these houses were the famous colonists who, with the exception of a few who remained royalists, played prominent roles in the struggle for freedom. They are the patriots who obtained their niche in history as having fought and struggled in making America a free and great nation.

Some of this atmosphere of the exciting past comes to the Museum with this exhibition of textiles from these old homes. The walls of the Museum Gallery hung with five-yard lengths of these colorful textiles radiate a galaxy of colors in shimmering and lustrous silks. Framed charts are included with photographs of exteriors and interiors of each house. A brief resume of the lives of the owners, the period of architecture, and a description of color schemes of the rooms and contents are also given.

It is an exhibit of interest and educational value to every American, and alike, instructive to interior decorators and students of interior design. College and public school students studying American history will be enlightened as to how their famous forefathers lived.

by Donald F. Hoffmeister, Assistant Professor of Zoology and Curator of the Natural History Museum, University of Illinois

Photograph by E. P. Haddon, Fish and Wild Life Service

Although for many years the badger was common in Illinois, it all but vanished from this State about the first half of the 19th century. By 1861, an Illinois biologist commenting on the badger wrote that the species had “nearly abandoned the State,” and by the latter part of the past century the badger was definitely on the wane in Illinois.

But strangely enough, within recent years the badger once more has increased in numbers in northern Illinois and has reinvaded some of the territory it formerly occupied in central Illinois. It is most abundant in our northwestern counties, but even as far south as Fulton County this animal has been seen in nearly a dozen different localities in the past ten years. Two badgers were taken nearly as far east as the Indiana line in 1953. The badger, in spite of man’s attempt to control it, apparently is increasing and spreading.

Although you may live in an area where the badger is common, it would not be surprising if you had never seen this animal, for it is abroad principally at night. However, its presence is usually well known by the abundance of its diggings. The badger is excellently equipped to dig, with powerful forelegs tipped with long, strong claws. It is squat and streamlined for getting through—not over—the ground. More than once, a group of men have cornered a badger in a shallow burrow, but one badger with its own digging apparatus extended the burrow faster than the crew of men could shovel. When pursuing or pursued, the badger never rests on its “shovels”, but keeps them going at such a rapid pace that the tunnel behind is soon filled with 422 moved dirt. The front legs loosen the dirt and push it under the animal, where the hind legs pick up the process and continue the earth on out behind. The operation proceeds like an endless track, without a wasted motion. As many as ten men, all equipped with shovels, have failed to keep up with the excavating of a badger, and the latter has escaped their intents. Ten men against a 30-pound badger! No wonder it has been called a master excavator. With the powerful front legs, the badger is not readily deterred in its burrowing. I have seen where a badger had decided to come to the surface from its subterranean burrow beneath a heavily macadamized road. The well-packed rocks, gravel, and tar, some four or five inches thick, were torn away and a sizeable hole made as if no roadway were there. A captive badger was given the run of a concrete basement. This seemed like a safe enough place. However, the animal found a crack and enlarged it until he was successful in removing a piece of concrete.

The badger is yellowish gray in color, with a conspicuous white stripe on the head, extending from the nose over the forehead, and disappearing on the back. Because the animal belongs to the weasel and skunk family, it possesses scent glands and a strong odor which is emitted only infrequently. When tormented, the badger holds its stubby tail erect, skunk-fashion, and hisses in a menacing way.

In Illinois, the badger is at home on the rolling, sandy prairies, as well as on prairies with heavier soils. Franklin ground squirrels, thirteen-lined ground squirrels, woodchucks, and meadow mice provide food for the badger population. When prey is sensed in the badger’s underground burrow, the dirt flies until the hunter has it securely in mouth. Snakes, frogs, insects, and rabbits also are eaten; and because the majority of these items in its diet are pests of man, the badger is considered a most important animal in northern Illinois in keeping small mammals in check and is vastly underrated as a natural control of many of our pests. To condemn the woodchuck and badger, or the ground squirrel and badger, in the same breath would be like despising both garbage and the garbage man.

Badgers have a single litter of young each year in May or June. The young are cared for in a nest at the end of a protective subterranean burrow. In wintertime, badgers are said to hibernate, but they do not do so in the strict sense of the word. They may become inactive during periods of extreme cold, but they do not enter into the deep sleep, with reduced metabolic activities, that the woodchucks and ground squirrels do in Illinois.

In our State, the badger has few, if any, enemies, other than man. Man traps the badger, makes unusable some of its preferred habitat, poisons off the squirrels and woodchucks which are its preferred source of food, and runs it down on the highway. The fur of the badger nowadays has little or no value, but in former years it was in demand, and a badger hide, at inflated prices, would have been worth as much as ten dollars. Conservationists maintain that it is unwise not to give some protection to one of our most interesting mammals, a potentially valuable fur-bearer, and a foremost controller of rodent pests.

May the “diggings” of the badger, the next time you encounter them, thrill you with the thoughts of one of Illinois’ first and foremost engineers, a master excavator.

by Milton D. Thompson, Assistant Director

There will be two identical programs each Saturday this fall, on four consecutive Saturdays from October 31 to November 21, one at 9:00 A.M. and the second at 10:30 A.M. in the auditorium of the Centennial Building. This double program is offered in response to the tremendous crowds with standing room only which we experienced last spring. We will have room for between 1200 and 1300 persons each Saturday. Parents and group leaders are invited to attend with their young people. We appreciate a few adults scattered through the audience.

Out-of-town groups making reservations in advance will have a block of seats reserved for them until five minutes before starting time. These Saturday morning programs and a visit to the Museum, Lincoln’s Home, Lincoln’s Tomb, and perhaps a trip out to New Salem make a wonderful weekend excursion for your club or class, and these interesting places are not nearly as crowded in the fall as in the spring.

9:00 A.M. and 10:30 A.M.

About 1 Hour and 15 Minutes Each

October 31—The Forgotten Village. This is the story of a small Mexican village, a primitive place, where the people prefer the chants and lotions of their “Witch Doctor” or “Wise Woman” to the modern knowledge of the village teacher. It is a stirring and vigorous film with the thrills and suspense of a Hollywood production.

November 7—Wedding of Palo. An exciting story of Greenland Eskimo life filmed by that famous Danish Arctic explorer, Knud Rasmussen. The sound track is in native Eskimo with English titles; there is a rousing surprise-ending to this tale of the Far North.

November 14—Wildlife Wonders. Presented in person by Drs. Lorus and Margery Milne, a “Western movie” like no other Western, for this is the story of wildlife of the Jackson Hole country of Wyoming. We will see elk roaming in herds among the quaking aspen trees, pronghorn antelope and badger in the sagebrush, moose browsing along the Snake River, buffalo taking dust baths, and the rare trumpeter swans. Drs. Lorus and Margery Milne who tell this tale will be here in person under the auspices of Audubon Screen Tours.

November 21—American Pioneer Highlights. This is the presentation of three films on exciting pioneer episodes of American history—The Kentucky Pioneers; Daniel Boone; and Pocahontas, the Indian girl who saved Captain John Smith and Jamestown. The trio forms an interesting story of some of America’s spectacular historic pioneer events.

In the new novel, Three Rivers South, a Tale of Young Abe Lincoln, Virginia S. Eifert, editor of The Living Museum, has written a story based on Abraham Lincoln’s famous flatboat trip in the spring of the year, 1831. Into the fabric of fiction, Mrs. Eifert has woven the few known facts of this obscure period in Lincoln’s life, and has created a narrative of adventure down three rivers of Mid-America.

These three streams are the Sangamon, the Illinois, and the Mississippi. The tale begins with young Abe and his kinsmen building a flatboat at Sangamo Town because their employer had neglected to procure a boat at the specified time in order to haul a load of corn and pork down to New Orleans. The story covers the month occupied in building the boat, the month enroute down the flooding rivers to the rowdy, elegant city of New Orleans, where the three spent a month exploring the city before returning to the Illinois country where Abe had a job at New Salem.

Three Rivers South has been capably and dramatically illustrated by one of America’s foremost artists, Thomas Hart Benton. It was published in September by Dodd, Mead and Company, New York, and is priced at $2.95. It may be obtained from your local book shop and from the Book Department of the Illinois State Museum.

The Living Museum

THE ILLINOIS STATE MUSEUM

Springfield, Illinois

Return Postage Guaranteed

Sec. 34.65(e) P. L. & R.

U. S. POSTAGE

PAID

Springfield, Illinois

Permit No. 878