TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

This book is a collection of twenty separate ‘Chap-books’. Each Chap-book has its own page numbering from 1 to 24.

There is only one Footnote, which has been placed at the end of its Chap-book.

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Many minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book.

THE

SCOTTISH CHAP LITERATURE

OF LAST CENTURY CLASSIFIED

RELIGIOUS AND SCRIPTURAL.

GLASGOW:

ROBERT LINDSAY, QUEEN STREET.

1877.

THE LIFE

AND

MERITORIOUS TRANSACTIONS,

OF

JOHN KNOX,

THE GREAT SCOTTISH

REFORMER.

GLASGOW:

PRINTED FOR THE BOOKSELLERS.

At the Reformation one half of the lands of Scotland were the property of the church. David I. had made over almost the whole of those belonging to the crown, and his example was imitated, not only by many of his successors, but by all orders of men, with whom the founding a monastery, or endowing a church, was thought to be a sufficient atonement for the breach of every command in the decalogue.

Besides the influence derived from the nature and extent of their property, generally let on lease, on easy terms, to the younger sons and dependants of great families, the weight the clergy had in Parliament was very considerable. The number of temporal barons being extremely limited, and the lesser barons and representatives of boroughs looking upon it as a hardship to attend, combined with the mode of choosing the Lords of the Articles. Its proceedings in a great measure were left under their direction and control.

The Lords of the Articles were a Committee whose business it was to prepare and digest all matters that were to be laid before Parliament. Every motion for a new law was made in this committee, and approved or rejected by the members of it; what they approved was formed into a bill, and presented to Parliament; what they rejected could not be introduced into the house. This committee[4] owed the extraordinary powers vested in it to the military genius of the ancient nobles, and in this way not only directed all the proceedings of Parliament, but possessed a negative before debate. It consisted of eight temporal and eight spiritual lords, of eight representatives of boroughs, and of eight great officers of the crown, and when its composition is considered, it will easily be seen how much influence it would add to the already too great power of the clergy.

Their character also was held sacred; neither were they subject to the same laws, nor tried by the same judges as the laity, a remarkable instance of which occurred on the trial of the murderers of Cardinal Beaton, one of whom was a priest. He was claimed by a delegate from the clerical courts, and exempted from the judgement of Parliament on that account.

By their reputation for learning, they almost wholly engrossed the high offices of emolument and trust in the civil government; but even this was not for acting in their capacity of confessors, they made use of all these motives which operate so powerfully on the human mind, to promote the interest of the church, so that few were allowed to leave the world without bestowing on her some marks of their liberality, and where credulity failed to produce this effect, they called in the aid of law. (When a person died intestate, by the 22d Statute of William the Lion, the disposal of his effects was vested in the bishop of the diocese, after paying his funeral charges and debts, and distributing among his kindred the sums to which they were respectively entitled, it being presumed that no Christian[5] could have chosen to leave the world without destining some of his substance to pious purposes.) Their courts had likewise the cognisance of all testamentary deeds and matrimonial contracts, and to these engines of power, and often in their hands of oppression, they super-added the sentence of excommunication, which besides depriving the unhappy victim on whom it fell of all Christian privileges, cut him off from every right as a man or citizen. To these, and other causes of a similar nature, may be ascribed the power of the Popish church; and to these, also, combined with the celibacy to which by the rule of their church they were restricted, may be attributed the dissolute and licentious lives of the clergy, which in the end destroyed that reputation for sanctity, the people had been accustomed to attach to their character.

According to the accounts of the reformers, confirmed by several popish writers, the manners of the Scottish clergy were indecent in the extreme. Cardinal Beaton celebrated the marriage of his eldest daughter with the son of the Earl of Crawford, with an almost regal magnificence, and maintained a criminal correspondence with her mother to the end of his days. The other prelates were not more exemplary than their primate, and the contrast between their lives, and those of the reformers, failed not to make a considerable impression on the minds of the people. Instead of disguising their vices the Popish clergy affected to despise censure; instead of endeavouring to colour over the absurdity of the established doctrines, or found them on Scripture, they left them to the authority of the church and decrees of the councils; the only apology they have[6] ever been able, even to the present day, to offer for the monstrous absurdity of their system. The duty of preaching was left to the lowest and most illiterate of the monks.

The following anecdote will give a lively idea of their mode of preaching:—The prior of the Black Friars at Newcastle, in a sermon at St Andrews, asserted that the Paternoster should be said to God only, and not the saints. This doctrine not meeting the approbation of the learned of that city, they appointed a Gray Friar to refute it, who choose for his text, “Blessed are the poor in spirit,” which he illustrated in this manner. Seeing we say, good day, father, to any old man in the street, we may call a saint pater, who is older than any alive; and seeing they are in heaven, we may say to any of them, “Our father who art in heaven;” seeing they are holy, we may say, “hallowed be thy name;” and, since they are in the kingdom of heaven, may add, “thy kingdom come;” and as their will is God’s will, “thy will be done;” but when he come to “give us this day our daily bread;” he was much at a loss confessing it was not in the power of the saints to give us our daily bread; “yet they may pray to God for us,” he said, “that he may give us our daily bread.” The rest of his commentary being not more satisfactory, set his audience a laughing and the children on the streets calling after him, Friar Paternoster, he was so much ashamed that he left the city.

The only device by which they attempted to bring back the people to their allegiance was equally unfortunate and imprudent; they had recourse to false miracles, which the vigilance of the refor[7]mers detected and exposed to ridicule. The bare-faced impositions that were practised by the monks on the credulous, are almost inconceivable.—Among other customs of those times, it was common for them to travel to Rome and come home laden with relics, blessed by his holiness, dispensations for sin, by which they wheedled the credulous out of their money. One of these, on a holiday, endeavouring to vend his wares to the country people, among other things shewed them a bell with a rent in it, possessing the virtue of discovering the truth or fallacy of an oath; for, as he pretended, if any one swore truly, with his hand on the bell, he could easily remove it, without any change; but if the oath was false, his hand would stick to it, and the bell rent asunder. A farmer, rather more shrewd than the rest of his auditors, suspecting the truth of this assertion, asked liberty to take an oath in the presence of those assembled, about an affair which nearly concerned him. The monk could not refuse; and the farmer addressing the crowd, said, “Friends, before I swear, you see the rent, how large it is, and that I have nothing on my fingers to make them stick to the bell.” Then laying his hand on it, he took this oath.—“I swear, in the presence of the living God, and before these good people, that the pope of Rome is Antichrist, and that all the rabble of his clergy, cardinals, archbishops, bishops, priests, monks, with all the rest of the crew, are locust, come from hell, to delude the people, and to withdraw them from God; moreover, I promise they will all return to hell;” and lifting his hand he added. “See, friends, I have lifted my hand freely from the bell, and the rent[8] is no larger, this sheweth that I have sworn the truth.”

The cause of reformed religion, was powerfully supported by the ambition of the Queen-dowager. (Mary of Guise) After the death of James V. her husband, the Earl of Arran, was appointed Regent of the kingdom during the minority of her daughter; and from that situation she wished to exclude him, that she might enjoy the first honours of the state alone, and promote the designs of her brothers upon Scotland. For this purpose she applied to the favourers of the Reformation, as being the most numerous of the Regent’s enemies, and forming a respectable body in the state; and although her promises of protection were insincere, they, in a very considerable degree, abated the fury of persecution.

John Knox, who contributed so much, both by precept and example, to work out the Reformation from Popery; was the descendant of an ancient family, and born at Gifford, near Haddington, in 1505. On finishing his education at the grammar school, he was removed to St. Andrew’s, to complete his studies under the celebrated John Mair, by whose instructions he made such progress that he received orders before the time prescribed by the rules of the church. After this, he quitted scholastic learning, so much in reputation at that period, and applied himself with diligence to the reading of the fathers of the church, particularly St Angustine, from which, attending the preaching of one Thomas Enillam, a Black Friar, and the conversation of Mr George Wishart, a celebrated reformer, who came from England in 1545 with the commis[9]sioners sent by Henry VIII. to conclude a treaty with the Earl of Arran, after the death of James V. he attained a more than ordinary degree of scriptural knowledge, and entirely renounced the Roman Catholic religion.

On leaving St Andrew’s, Mr Knox acted as tutor to the sons of Douglas of Longniddry, and Cockburn of Ormiston, whom, besides the different branches of common education, he carefully instructed in the principles of the reformed religion, having composed a catechism for their use, besides reading lectures to them on various portions of the scriptures. In this practice he continued till Easter 1547, when werried out by the repeated persecutions of Cardinal Beaton, he left Longniddry for St. Andrew’s, resolved to visit Germany, the state of England proving unfavourable to his views. Against taking this step, however, he was persuaded by the gentlemen whose children he had the charge, to remain in St. Andrews, the castle of that place being in the hands of the reformers.

Here he continued to teach his pupils in the usual manner, but his lectures were now attended by a number of people belonging to the town, who earnestly intreated him to preach in public. This task he at first declined, but afterwards accepted a call from the pulpit, and in his very first sermon discovered such zeal, learning, and intrepidity, as evinced the prudence of their choice, and how eminently qualified he was for the discharge of those duties. This success caused such alarm among the Popish clergy, that a letter was sent to the sub-prior by the abbot of Paisley, natural brother of the Regent, who had been nominated to the archbish[10]opric reproving him for his negligence, in allowing such doctrines to be taught without opposition. A meeting of the clergy was held in consequence, and every scheme they could devise put in practice to hurt Mr Knox’s usefulness; but, in a public disputation, he replied to all their arguments with so much acuteness as completely to silence them, and gained many proselytes, who made prefession of their faith by partaking of the communion openly, which he was the first to administer in the manner practised at present.

This success was not of long duration, for a body of French troops was sent to besiege the castle, and it was compelled to surrender on the 23d July, when he, along with the garrison, was sent prisoner to France, and confined in the gallies till the year 1549. On obtaining his liberty he retired to England, where he preached sometime at Berwick, afterwards at Newcastle and London, and was at last chosen one of the itinerants appointed by Edward VI. to preach the Protestant doctrine through England. Upon the death of that prince, on the 6th July, 1553, he went to Geneva, where he resided when he was chosen by the English church at Frankfort, on the 24th September, 1554, to be their pastor, a situation he accepted by the advice of the celebrated John Calvin, but which he did not long enjoy, for having opposed the introduction of the English liturgy, and refused to celebrate the communion according to the forms prescribed by it, he was deprived of his office; and, such was the malice of his enemies, that, taking advantage of a passage in his “Admonition to England,” wherein he compares the Emperor to[11] Nero, and the Queen of England to Jezebel, they accused him to the magistrates of treason. These gentlemen perceiving the spirit by which his accusers were actuated, found means to apprise him of his danger; and on the 26th march, 1555, he left Frankfort for Geneva, from whence he proceeded to Dieppe, and shortly afterwards to Scotland, where he arrived in the month of August.

On his arrival he found the reformers much increased in number, and after assisting them to rectify some errors which had crept into their practice, accompanied John Erskine of Dun to his seat in the Mearns, where he continued a month, preaching to the principle people in that country. He afterwards resided at Calder-house, the residence of Sir James Sandilands, where he was attended by a number of personages of the first rank; and, among others, by the prior of St Andrew’s afterwards earl of Moray. During the winter he visited Edinburgh; preached in many places of Ayrshire; and in the beginning of 1556, at the request of the earl of Glencairn, administered the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper to his lordship’s family, and a number of friends, at his seat of Finlayston.

In this way did Mr Knox continue preaching, sometimes in one place, and sometimes in another, when his success excited so much attention that the Popish clergy summoned him to appear before them, on the 15th of May, in the church of the Black Friars in Edinburgh. He did appear, but attended by such a number of followers that the clergy deemed it prudent to desist from their intended prosecution; and that same day he addressed a[12] much greater audience than ever he had done on any prior occasion, and continued to do so for ten days.

The earl of Glencairn, one of his firmest friends, prevailed on the earl Marshal, and Mr Henry Drummond, to attend one of Mr Knox’s sermons, they were so highly gratified with it that they persuaded him to address a letter to the Queen, in the hope she also might be induced to hear the doctrine of the reformers. In this letter, contending for the truth of what he taught, he says, “Albeit, Madam, that the messengers of God are not sent this day with visible miracles, because they teach no other doctrine than that which is confirmed with miracles from the beginning of the world, yet will not he (who hath promised to take charge over his poor and little flock to the end) suffer the contempt of their ambassage to escape punishment and vengeance, for the truth itself hath said, ‘he that heareth you heareth one, and he that contemneth you contemneth one.’ I do not speak unto you, Madam, as Pasquillus doth to the Pope and his carnal cardinals, in the behalf of such as dare not utter their names, but I come in the name of Christ Jesus; affirming, that the religion ye maintain is damnable idolatry, which I offer myself to prove, by the most evident testimony of God’s Scriptures; and in this quarrel I present myself against all the Papists in the realm, desiring no other armour but God’s holy word, and the liberty of my tongue.” It was delivered to the Queen by the earl of Glencairn, and by her to the bishop of Glasgow, ( nephew of Cardinal Beaton) with this observation, “Please you, my lord, to read a pasquil,” which[13] coming to the ears of Mr Knox, was the occasion of his making a number of additions when the letter was printed afterwards at Geneva.

At this time he received letters from the English church at Geneva, which had separated from the one at Frankfort, commanding him, “in God’s name, as he was their chosen pastor, to repair to them for their comfort.” Having preached in almost every congregation he had formerly visited, and sent his wife and mother-in-law before him to Dieppe, he sailed from Scotland in the month of July for Geneva. No sooner had he left the kingdom than the bishops summoned him to answer a charge of heresy; and, on his non-appearance, burnt him in effigy at the cross of Edinburgh. Against this sentence, in 1558, he published his “Appellation,” addressed to the “Nobility and Estates of Scotland.” In this composition, which has been much admired, after appealing “to a lawful and general council,” and requiring of them that defence which, as princes of the people, they were bound to give him, he adds, “these things I require of your honours to be granted unto me, viz. that the doctrine which our adversaries condemn for heresy may be tried by the plain and simple word of God; that the just defences be admitted to us that sustain the battle against this pestilent battle of Antichrist; and that they be removed from judgment in our cause, seeing that our accusation is not intended against any one particular person, but against that whole kingdom which we doubt not to prove to be a power usurped against God, against his commandments, and against the ordinance of Christ Jesus, established in his church[14] by his chief apostles; yea, we doubt not to prove the kingdom of the Pope to be the kingdom and power of Antichrist, and therefore, my lords, I cannot cease, in the name of Christ Jesus, to require of you that the matter may come to examination, and that ye, the estates of the realm, by your authority, compel such as will be called bishops, not only to desist from their cruel murdering of such as do study to promote God’s glory, in detecting and disclosing the damnable impiety of that man of sin the Roman Antichrist; but, also, that ye compel them to answer to such crimes as shall be laid to their charge, for not righteously instructing the flock committed to their care.”

In March, 1557, sensible of his importance, a letter, subscribed Glencairn, Erskine, Lorn, and James Stuart, was transmitted to Mr Knox at Geneva, entreating him to return home. Having communicated its contents to his congregation, for which he provided another minister, and taking the advice of John Calvin, and other ministers, he set out for Scotland.

Addressing himself to the lords who had invited his return, Mr Knox expostulates with them on their rash conduct, as having a tendency to cause both them and him to be evil spoken of.—“For either,” said he, “it shall appear that I was marvellous vain, being so solicited, where no necessity required, or else that such as were my movers thereto lacked the ripeness of judgment in their first vocation.” Along with this letter he sent one to the whole nobility, and others to particular gentlemen, advising them in what manner they ought to proceed. On their receipt a new consultation was held,[15] and a bond subscribed at Edinburgh on the 13th December, 1557, whereby they agreed to “forsake and renounce the congregation of Satan, with all the superstitious abominations and idolatry thereof.” From this period those subscribing, and their adherents, were known by the title of the Congregation. Previous to this agreement, however, a number of letters were sent off to Mr Knox, and to John Calvin, that he might use his influence in persuading him to return.

This year (1558,) the Queen Regent, through the concurrence of the Protestant party in Parliament, obtained an act to be passed, conferring the matrimonial crown on the Dauphin, the husband of her daughter, the unfortunate Mary. They had been induced to forward her views in this favourite scheme, that they might obtain from her an exemption from that tyranny with which the ancient laws armed the ecclesiastics against them, and enjoy the free exercise of their religion. No sooner, however, had she obtained the gratification of her wishes, than the accomplishment of a new scheme, the placing her daughter on the throne of England, and to which she had been prompted by the ambition of her brothers, the princes of the house of Lorraine, at that time in the plenitude of their power at the Court of France, rendered an union with the Catholics necessary. It was vain to expect the assistance of the Scots Protestants to dethrone Elizabeth, whom all Europe considered as the most powerful defender of the Reformed faith. She therefore began to treat them with coldness and contempt, and not only approved the decrees of a convocation of the Popish clergy, in which the prin[16]ciples of the Reformation were condemned, but at the same time issued a proclamation enjoining the observance of Easter according to the ritual of the Romish church.

Alarmed at these proceedings, and still more at an order summoning all the Reformed clergy in the kingdom, to attend a court of justice at Stirling, on the 10th May, 1559, the earl of Glencairn, and Hugh Campbell of Louden, were deputed to wait on her and intercede in their behalf. On urging their peaceable demeanour, and the purity of their doctrine, she said, “In despite of you, and your ministers both, they shall be banished out of Scotland, albeit they preached as true as ever did St. Paul.” And on pleading her former promises of protection, she replied, “The promises of princes ought not to be too carefully remembered, nor the performance of them exacted unless it suits their convenience.”

Perth, in the meantime, having embraced the Reformed religion, added to the rage which agitated the Queen against the Protestants, and she commanded the provost (Patrick Ruthven,) to suppress all their assemblies. The answer of this gentleman deserves to be recorded for its manly freedom. “I have power over their bodies and estates,” said he, “and these I will take care shall do no hurt; but have no dominion over their consciences.” The day of trial now approached, and the town of Dundee, and the gentlemen of Angus and Mearns, in comformity of an old custom which prevailed in Scotland, resolved to accompany their pastors to the place of trial. Intimidated by their numbers, though unarmed, she prevailed on John[17] Erskine of Dun, a person of great influence among them, to stop them from advancing nearer to Stirling, while she, on her part, promised to take no further steps towards the intended trial. This proposition was listened to with pleasure, the preachers and some of the leaders remained at Perth, and the multitude quietly dispersed to their respective homes.

Notwithstanding this promise, on the 10th May, the queen proceeded to the trial of the persons summoned; and, on their failing to appear, sentence of outlawry was pronounced upon them. This open and avowed breach of faith added greatly to the public irritation, and the Protestants boldly prepared for their defence. Mr Erskine having joined his associates at Perth, his representation of the Queen’s irreconcilable hatred so inflamed the people, that scarcely the authority of the magistrates, or the exhortations of their preachers, could prevent them from proceeding to acts of violence.

At this juncture, Mr Knox landed in Scotland from France, and, after residing two days in Edinburgh, joined his brethren in Perth, that he might aid them in their cause, and give his confession along with theirs. On the 11th, the day after the sentence of outlawry was pronounced, he made a vehement discourse against idolatry, and while the minds of the people were yet in a state of agitation, from the impression made upon them by his sermon, a priest prepared to celebrate mass, which made a youth observe, “This is intolerable, that when God in his word hath plainly condemned idolatry we shall stand and see it used in despite.” The irritated priest struck him a blow on the ear,[18] and the youth in revenge threw a stone at him, which broke an image of one of the saints. This was the signal of tumult, and ere two days had elapsed, all the churches and convents about Perth were destroyed. Such was the anger of the Queen on receiving this intelligence, that she avowed to reduce Perth to ashes, and ordered M. D’Ossal, the commander of a corps of French auxiliaries, at that time in the service of Scotland, instantly to march, and carry her threats into execution. Both parties, however, were desirous of accommodation, and a treaty was concluded, in which it was stipulated that the two armies should be disbanded, the gates of Perth set open to the queen, but that none of her French soldiers should approach within three miles of that city, and that a Parliament should be immediately held to settle the remaining differences.

No sooner were the Protestant forces disbanded, than the Queen violated every article of the treaty. In consequence of which the earl of Argyle, and the prior of St Andrew’s, who had been her commissioners for settling the peace, with some other gentlemen, openly left her. Having warned the confederates of her intention to destroy St Andrew’s and Cupar, a considerable army was soon assembled, which assaulted Crail, broke down the altars and images, and proceeded thence to St Andrew’s, where they levelled the Franciscan and Dominican monasteries to the ground. The Queen immediately gave orders to occupy Cupar, with the intention of attacking them at St Andrew’s, but in this she was anticipated, an army equal to her own having occupied the place two days before. Finding herself[19] too weak to encounter them in the field, she had again recourse to negotiation; but mindful of her former duplicity, the Protestants would only agree to a truce for eight days, by which the Duke of Chatelherault and D’Ossal became bound to transport all the French soldiers to the other side of the Frith, and send commissioners to St Andrew’s with full powers to conclude a formal treaty of peace.

Several days elapsed without any person appearing on the part of the queen, and suspecting some new plan to entrap them, the Protestants, after concerting measures to expel the French garrison from Perth, wrote to her Majesty, complaining that the terms of the first treaty were still unfulfilled, and begging her to withdraw her troops from that city in conformity with its stipulations. Their letters remaining unnoticed, they laid siege to Perth, which surrendered, after a feeble resistance, on the 26th June, 1559.

Being informed that the Queen resolved to seize Stirling, and cut off the communication between the reformers on the opposite sides of the Frith, by a rapid march they frustrated her plans, and in three days, after they had made themselves masters of Perth, the victorious reformers entered Edinburgh. The Queen on their approach retired to Dunbar,—where she amused them with hopes of an accommodation, in the expectation of being joined with reinforcements from France. Intelligence, in the meantime, was received of the death of the French king, which, while it was favourable to the cause of the reformers, rendered their leaders more negligent and secure. Numbers of them left the city on their private affairs, their followers were obliged to dis[20]perse for want of money, and those who did remain were without discipline or restraint. The Queen receiving advice of this, by means of her spies, marched with all the forces she could muster directly to Edinburgh, and possessed herself, on the 25th of July, of Leith. She consented, however, to a truce, to continue till the 5th January, 1560, by which liberty of conscience was secured; Popery was not to be established again where it had been suppressed, the reformers were not to be hindered from preaching wherever they might happen to be, and no garrison was to be stationed within the city. These terms were preserved till she received the expected reinforcements, when she fortified Leith, from which all the efforts of the reformers were unable to dislodge her troops. A mutiny also breaking out among their soldiers for want of pay, and having been defeated in two skirmishes with the French troops, it was resolved, by a majority of the lords of the congregation, to retire to Stirling. This rash step was productive of great terror and confusion, and contrary to the advice of Knox; who, notwithstanding, followed the fortunes of his friends, animating and reviving them by his discourses, and exhorting them to constancy in the good cause.

At a meeting held shortly after their arrival at Stirling, it was resolved, to despatch William Maitland, who had lately deserted the Queen’s party to England, to implore the assistance of Queen Elizabeth, and a treaty was at last concluded, by which a body of troops was sent to their assistance. These being joined by most of the Scottish nobility, a peace was established on the 8th July, 1560, by which[21] the reformed religion was fully established in Scotland.

On the abolition of Popery, the form of church goverment establishment in Scotland was, upon the model of the church at Geneva, warmly recommended to his countrymen by Knox, as being farthest removed from all similarity to the Romish church; and at his suggestion, likewise, the country was divided into twelve districts, for the more effectually propagating the doctrines of the Reformation, of which Edinburgh was assigned to his care. Knox, assisted by his brethren afterwards composed a confession of Faith, and compiled the first books of discipline for the government of the church. These were ratified by a convention of Estates, held in the beginning of the following year (1571), and an act passed prohibiting mass and abolishing the authority of the Pope.

On the return of Mary, daughter of Mary of Guise, from France, and so well known afterwards throughout all Europe for her beauty, her accomplishments, and her misfortunes, after the death of her husband Francis II. the celebration of mass in the chapel royal excited a great tumult, many crying out, “The idolatrous papist shall die the death, according to God’s law;” and John Knox, in a sermon preached the Sunday following after showing the judgments inflicted on nations for idolatry, added, “one mass is more fearful to me than if ten thousand armed enemies were landed in any part of the realm, of purpose to suppress the whole religion.” In consequence of this language he was sent for by the queen, who accused him of endeavouring to excite her subjects to rebellion, of having[22] written against her lawful authority, and of being the cause of great sedition. To this he answered, among other things, “that if to teach the word of God in sincerity, if to rebute idolatry, and to will a people to worship God according to his word, be to raise subjects against their princes, then cannot I be excused; for it hath pleased God in his mercy to make me one amongst many to disclose unto this realm the vanity of the papistical religion.—And touching that book, that seemeth so highly to offend your majesty, it is most certain that if I wrote it I am content that all the learned of the land should judge of it. My hope is, that, so long as ye defile not your hands with the blood of the saints of God, that neither I nor that book shall either hurt you or your authority; for, in very deed, Madam, that book was written most especially against that wicked Mary of England.” To a question by the Queen, if subjects, having power, may resist their princes? He boldly answered they might, “if princes do exceed their bounds.” The following part of the dialogue will give a good idea of the character of Knox, and the freedom of his speech: Speaking of the church, the Queen observed, “but ye are not the church of Rome, for I think it is the true church of God.” “Your will, Madam,” said he, “is no reason; neither doth your thought make that Roman harlot to be the immaculate spouse of Jesus Christ. And wonder not, Madam, that I call Rome an harlot, for that church is altogether polluted with all kinds of spiritual fornication, as well in doctrine as in matters.” He had afterwards two other conferences with the queen,[23] at the last of which she burst into tears, crying out, “Never prince was used as I am.”

Knox’s situation became very critical in April, 1571, when Kircaldy received the Hamiltons, with their forces, into the castle. Their inveteracy against him was so great, that his friends were obliged to watch his house during the night. They proposed forming a guard for the protection of his person when he went abroad; but the governor of the castle forbade this, as implying a suspicion of him, and offered to send Melvil, one of his officers, to conduct him to and from church. “He wold gif the woulf the wedder to keip,” says Bannatyne. Induced by the importunity of the citizens, Kircaldy applied to the Duke and his party for a special protection to Knox; but they refused to pledge their word for his safety, because “there were many rascals and others among them who loved him not, that might do him harm without their knowledge.” Intimations were often given him of threatenings against his life; and one evening, a musket ball was fired in at his window, and lodged in the roof of the apartment in which he was sitting. It happened that he sat at the time in a different part of the room from that in which he had been accustomed to take his seat, otherwise the ball, from its direction, must have struck him. Alarmed by these circumstances, a deputation of the citizens, accompanied by his colleague, waited upon him, and renewed a request which they had formerly made, that he would remove from Edinburgh, to a place where his life would be in greater safety, until the Queen’s party should evacuate the town. But he refused to yield to them, apprehending that his enemies[24] wished to intimidate him into flight, that they might carry on their designs more quietly, and then accuse him of cowardice. Being unable to persuade him by any other means, they at last had recourse to an argument which prevailed. Upon this he consented, “sore against his will,” to remove from the city.

In May, 1571, at the desire of his friends, and for greater security, he left that city for St Andrew’s, where he remained until the August following. The cause that forced him to change his residence having ceased to operate, at the express desire of his congregation he again returned, but could not long continue to preside over it, on account of the exhausted state of his health; and on the 9th November, abmitted Mr James Lawson, formerly professor of philosophy at Aberdeen, to be his successor.

From this time till the 24th of the same month, when he expired, about eleven o’clock at night, in the 67th year of his age; his principal employment was reading the Scriptures and conversing with his friends; and over his remains, which were accompanied to the churchyard by the Earl of Morton, the Regent, and a number of other noblemen, and people of all ranks, his lordship pronounced the following eulogium: “Here lies a man, who in his life never feared the face of man; who hath been often threatened with dag and dagger, but yet hath ended his days in peace and honour.”

FINIS.

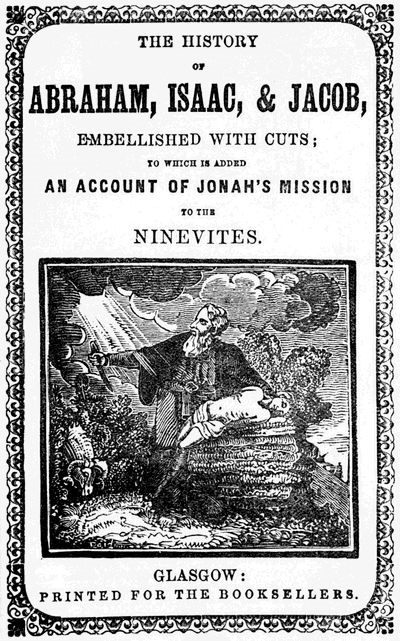

HISTORY

OF THE LIFE & SUFFERINGS

OF THE

REV. JOHN WELCH,

SOMETIME MINISTER OF THE GOSPEL AT AYR.

GLASGOW:

PRINTED FOR THE BOOKSELLERS.

Mr. John Welch was born a gentleman, his father being laird of Colieston, (an estate rather competent, than large, in the shire of Nithsdale) about the year 1570, the dawning of our reformation being then but dark. He was a rich example of grace and mercy, but the night went before the day, being a most hopeless extravagant boy: it was not enough to him, frequently when he was a young stripling to run away from the school and play the truant; but after he had passed his grammar, and was come to be a youth, he left the school, and his father’s house, and went and joined himself to the thieves on the English border, who lived by robbing the two nations, and amongst them he stayed till he spent a suit of clothes. Then he was clothed only with rags, the prodigal’s misery brought him to the prodigal’s resolution, so he resolved to return to his father’s house, but durst not adventure, till he should interpose a reconciler. So in his return homeward, he took Dumfries in his way where he had an aunt, one Agnes Forsyth, and with her he diverted some days, earnestly entreating her to reconcile him to his father. While he lurked in her house, his father came providentially to the house to salute his cousin, Mrs. Forsyth; and after[4] they had talked a while, she asked him, whether he had ever heard any news of his son John; to her he replied with great grief, O cruel woman, how can you name his name to me? The first news I expect to hear of him, is, that he is hanged for a thief. She answered, many a profligate boy had become a virtuous man, and comforted him. He insisted upon his sad complaint, but asked whether she knew his lost son was yet alive. She answered, Yes, he was, and she hoped he should prove a better man than he was a boy, and with that she called upon him to come to his father. He came weeping and kneeled, beseeching his father, for Christ’s sake, to pardon his misbehaviour, and deeply engaged to be a new man. His father reproached him and threatened him. Yet, at length, by the boy’s tears, and Mrs. Forsyth’s importunities, he was persuaded to a reconciliation. The boy entreated his father to send him to the college, and there to try his behaviour, and if ever thereafter he should break, he said he should be content his father should disclaim him for ever: so his father carried him home, and put him to the college, and there he became a diligent student, of great expectation, and shewed himself a sincere convert, and so he proceeded to the ministry.

His first post in the ministry was at Selkirk, while he was yet very young, and the country rude; while he was there, his ministry was rather admired by some, than received by many; for he was always attended by the prophet’s shadow, the hatred of the wicked; yea, even the ministers of the country, were more ready to pick a quarrel with his person, than to follow his doctrine, as may appear to this day in their synodical records, where we find he had many to censure him, and only some[5] to defend him; yet it was thought his ministry in that place was not without fruit, though he stayed but a short time there. Being a young man unmarried, he lodged himself in the house of one Mitchelhill, and took a young boy of his to be his bed-fellow, who to his dying day retained both a respect to Mr. Welch and his ministry, from the impressions Mr. Welch’s behaviour made upon his mind though but a child.

The special cause of his leaving Selkirk, was a profane gentleman in the country (one Scot of Headschaw, whose family is now extinct) but because Mr. Welch had either reproved him, or merely from hatred, Mr. Welch was most unworthily abused by the unhappy man, amongst the rest of the injuries he did him, this was one, Mr. Welch kept always two good horses for his use, and the wicked gentleman when he could do no more, either with his own hand, or his servants, cut off the rumps of the two innocent beasts, upon which followed such effusion of blood, that they both died, which Mr. Welch did much resent, and such base usage as this persuaded him to listen to a call to the ministry at Kirkcudbright, which was his next post.

But when he was about to leave Selkirk, he could not find a man in all the town to transport his furniture, except one Ewart, who was at that time a poor young man, but master of two horses, with which he transported Mr. Welch’s goods, and so left him, but as he took his leave, Mr. Welch gave him his blessing, and a piece of gold for a token, exhorting him to fear God, and promised he should never want, which promise, providence made good through the whole course of his life, as was observed by all his neighbours.

At Kirkcudbright he stayed not long; but there he reaped a harvest of converts, which subsisted long after his departure, and were a part of Mr. Samuel Rutherfoord’s flock, though not his parish, while he was minister at Anwith: yet when his call to Ayr came to him, the people of the parish of Kirkcudbright never offered to detain him, so his transportation to Ayr was the more easy.

Mr. Welch was transported to Ayr in the year 1590, and there he continued till he was banished, there he had a very hard beginning, but a good ending; for when he came first to the town, the country was so wicked, and the hatred of godliness so great, that there could not be found one in all the town, that would let him a house to dwell in, so he was constrained to accommodate himself in the best he might, in a part of a gentleman’s house for a time, the gentleman’s name was John Stewart, he was an eminent Christian, and a great assistant of Mr. Welch.

And when he had first taken up his residence in that town, the place was so divided into factions, and filled with bloody conflicts, a man could hardly walk the streets with safety; wherefore Mr. Welch made it his first undertaking to remove the bloody quarrelings, but he found it a very difficult work; yet such was his earnestness to pursue his design, that many times he would rush betwixt two parties of men fighting, even in the midst of blood and wounds.

His manner was, after he had ended a skirmish amongst his neighbours, and reconciled these bitter enemies, to cause them to cover a table upon the street, and there brought the enemies together, and begining with prayer he persuaded them to protest themselves friends, and then to eat and drink together, then last of all, he ended the work with[7] singing a psalm: after the rude people began to observe his example, and listen to his heavenly doctrine, he came quickly to that respect amongst them that he became not only a necessary counsellor, without whose counsel they would do nothing, but an example to imitate, and so he buried the bloody quarrels.

He gave himself wholly to ministerial exercises, he preached once every day, he prayed the third part of his time, was unwearied in his studies, and for a proof of this, it was found among his papers, that he had abridged Suarez’s metaphysics, when they came first to his hand, even when he was well stricken in years. By all which, it appears, that he has not only been a man of great diligence but also of a strong and robust natural constitution, otherwise he had never endured the fatigue.

But if his diligence was great, so it is doubted whether his sowing in painfulness, or his harvest in his success was greatest; for if either his spiritual experiences in seeking the Lord, or his fruitfulness in converting souls be considered, they will be found unparalleled in Scotland: and many years after Mr. Welch’s death, Mr. David Dickson, at that time a flourishing minister at Irvine, was frequently heard to say, when people talked to him of the success of his ministry, that the grape gleanings in Ayr, in Mr. Welch’s time, were far above the vintage of Irvine, in his own. Mr. Welch, in his preaching, was spiritual and searching, his utterance tender and moving; he did not much insist upon scholastic purposes, he made no shew of his learning. I once heard one of his hearers say, That no man could hear him and forbear weeping, his conveyance was so affecting. There is a large volume of his sermons, now in Scot[8]land, wherein he makes it appear, his learning was not behind his other virtues: this also appears in another piece, called Dr. Welch’s Armagaddon, printed, I suppose, in France, wherein he gives his meditation upon the enemies of the church, and their destruction; but the piece itself is rarely to be found.

Sometimes before he went to sermon, he would send for his elders, and tell them, he was afraid to go to pulpit because he found himself sore deserted; and thereafter desire one or more to pray, and then he would venture to pulpit. But, it was observed, this humbling exercise used ordinarily to be followed, with a flame of extraordinary assistance: so near neighbours are many times contrary dispositions and frames. He would many times retire to the church of Ayr, which was at some distance from the town, and there spend the whole night in prayer: for he used to allow his affections full expression, and prayed not only with audible, but sometimes, loud voice, nor did he irk, in that solitude, all the night over, which hath, it may be, occasioned the contemptible slander of some malicious enemies, who were so bold as to call him no less than a witch.

There was in Ayr, before he came to it, an aged man a minister of the town, called Porterfield, the man was judged no bad man, for his personal inclinations, but so easy a disposition, that he used many times to go too great a length with his neighbours in many dangerous practices; and amongst the rest, he used to go to the bow-butts and archery, on Sabbath afternoon, to Mr. Welch’s great dissatisfaction. But the way he used to reclaim him, was not bitter severity, but this gentle policy; Mr. Welch together with John Stewart, and Hugh Kennedy, his two intimate friends, used[9] to spend the Sabbath afternoon in religious conference and prayer, and to this exercise they invited Mr. Porterfield, which he could not refuse, by which means he was not only diverted from his former sinful practice, but likewise brought to a more watchful, and edifying behaviour in his course of life.

He married Elizabeth Knox, daughter to the famous Mr. John Knox, minister at Edinburgh, the apostle of Scotland, and she lived with him from his youth till his death. By her I have heard he had three sons: the first was called Dr. Welch, a doctor of medicine, who was killed in the low countries, and of him I never heard more. Another son he had most lamentably lost at sea, for when the ship in which he was embarked was sunk, he swam to a rock in the sea, but starved there for want of necessary food and refreshment, and when sometime afterward his body was found upon the rock, they found him dead in a praying posture upon his bended knees, with his hands stretched out, and this was all the satisfaction his friends and the world had upon his lamentable death, so bitter to his friends. Another he had who was heir to his father’s grace and blessings, and this was Mr. Josias Welch, minister at Temple-Patrick in the north of Ireland, commonly called the Cock of the Conscience by the people of that country, because of his extraordinary wakening and rousing gift: he was one of that blest society of ministers, which wrought that unparalleled work in the north of Ireland, about the year 1636, but was himself a man most sadly exercised with doubts about his own salvation all his time, and would ordinarily say, That ministers was much to be pitied, who was called to comfort weak saints and had no[10] comfort himself. He died in his youth, and left for his successor, Mr. John Welch minister at Iron-Gray in Galloway, the place of his grandfather’s nativity. What business this made in Scotland, in the time of the late Episcopal persecution, for the space of twenty years, is known to all Scotland. He maintained his dangerous post of preaching the gospel upon the mountains of Scotland, notwithstanding of the threatnings of the state, the hatred of the bishops, the price set upon his head, and all the fierce industry of his cruel enemies. It is well known that bloody Claverhouse upon secret information from his spies, that Mr. John Welch was to be found at some lurking place at forty miles distance, would make all that long journey in one winter’s night, that he might catch him, but when he came he always missed his prey. I never heard of a man that endured more toil, adventured upon more hazards, escaped so much hazard, not in the world. He used to tell his friends who counselled him to be more cautious, and not to hazard himself so much, That he firmly believed dangerous undertakings would be his security, and when ever he should give over that course and retire himself, his ministry should come to an end; which accordingly came to pass, for when after Bothwell bridge, he retired to London, the Lord called him by death, and there he was honourably buried, not far from the king’s palace.

But to return to our old Mr. Welch; as the duty wherein he abounded and excelled most was prayer, so his greatest attainments fell that way. He used to say, He wondered how a Christian could lie in bed all night, and not rise to pray, and many times he watched. One night he rose from his wife, and went into the next room, where he stayed so long[11] at secret prayer, that his wife fearing he might catch cold, was constrained to rise and follow him, and as she hearkened, she heard him speak as by interrupted sentences, Lord wilt thou not grant me Scotland, and after a pause, Enough, Lord, enough, and so she returned to her bed, and he following her, not knowing she had heard him, but when he was by her, she asked him what he meant by saying, Enough, Lord, enough. He shewed himself dissatisfied with her curiosity, but told her, he had been wrestling with the Lord for Scotland, and found there was a sad time at hand, but that the Lord would be gracious to a remnant. This was about the time when bishops first overspread the land, and corrupted the church. This was more wonderful I am to relate, I heard once an honest minister, who was a parishioner of Mr. Welch many a day, say, ‘That one night as he watched in his garden very late, and some friends waiting upon him in his house and wearying because of his long stay, one of them chanced to open a window toward the place where he walked, and saw clearly a strange light surrounding him, and heard him speak strange words about his spiritual joy,’ I do neither add nor alter, I am the more induced to believe this that I have heard from as good a hand as any in Scotland, that a very godly man, though not a minister, after he had spent a whole night in a country house, in the muir, declared confidently, he saw such an extraordinary light as this himself, which was to him both matter of wonder and astonishment. But though Mr. Welch had upon the account of his holiness, abilities, and success, acquired among his subdued people, a very great respect, yet was he never in such admiration, as after the great plague which raged in Scotland in his time.

And one cause was this: The magistrates of Ayr, forasmuch as this town alone was free, and the country about infected, thought fit to guard the ports with sentinels, and watchmen; and one day two travelling merchants, each with a pack of cloth upon a horse, came to the town desiring entrance that they might sell their goods producing a pass from the magistrates of the town whence they came which was at that time sound and free; yet not withstanding all this the sentinels stopt them till the magistrates were called; and when they came, they would do nothing without their minister’s advice: so Mr. Welch was called, and his opinion asked; he demurred, and putting off his hat with his eyes toward heaven for a pretty space, though he uttered no audible words, yet continued in a praying gesture: and after a little space told the magistrates they would do well to discharge these travellers their town, affirming with great asseveration, the plague was in their packs, so the magistrates commanded them to be gone, and they went to Cumnock, a town some twenty miles distant, and there sold their goods, which kindled such an infection in that place, that the living were hardly able to bury their dead. This made the people begin to think Mr. Welch as an oracle. Yet as he walked with God, and kept close with him, so he forgot not man, for he used frequently to dine abroad with such of his friends, as he thought were persons with whom he might maintain the communion of the saints; and once in the year he used always to invite all his familiars in the town to a treat in his house, where there was a banquet of holiness and sobriety.

And now the scene of his life begins for to alter;[13] but before his blessed sufferings, he had this strange warning.

One night he rose from his wife, and went into garden, as his custom was, but stayed longer than ordinary, which troubled his wife, who, when he returned, expostulated with him very hard, for his staying so long to wrong his health; he bid her be quiet, for it should be well with them. But he knew well, he should never preach more at Ayr; and accordingly before the next Sabbath, he was carried prisoner to Blackness castle. After that, he, with many others were brought before the council of Scotland, at Edinburgh, to answer for their rebellion and contempt, in holding a general assembly, not authorised by the king. And because they declined the secret council, as judges competent in causes purely spiritual, such as the nature and constitution of a general assembly is, they were first remitted to the prison at Blackness, and other places. And thereafter, six of the most considerable of them, were brought under night from Blackness to Linlithgow before the criminal judges, to answer an accusation of high treason, at the instance of Sir Thomas Hamilton, king’s advocate, for declining, as he alledged, the king’s lawful authority, in refusing to admit the council judges competent in the cause of the nature of church judicatories; and after their accusation, and answer was read, by the verdict of a jury of very considerable gentlemen, condemned as guilty of high treason, the punishment continued till the king’s pleasure should be known, and thereafter their punishment was made banishment, that the cruel sentence might someway seem to soften their severe punishment as the king had contrived it.

But before he left Scotland, some remarkable[14] passages in his behaviour are to be remembered. And first when the dispute about church-government began to warm; as he was walking upon the street of Edinburgh, betwixt two honest citizens, he told them, they had in their town two great ministers, who were no great friends to Christ’s cause, presently in controversy, but it should be seen, the world should never hear of their repentance. The two men were Mr. Patrick Galloway, and Mr. John Hall; and accordingly it came to pass, for Mr. Patrick Galloway died easing himself upon his stool; and Mr. John Hall, being at that time in Leith, and his servant woman having left him alone in his house while she went to the market, he was found dead all alone at her return.

He was sometime prisoner in Edinburgh castle before he went into exile, where one night sitting at supper with the lord Ochiltry, who was an uncle to Mr. Welch’s wife, as his manner was, he entertained the company with godly and edifying discourse, which was well received by all the company save only one debauched popish young gentleman, who sometimes laughed, and sometimes mocked and made faces; whereupon Mr. Welch brake out into a sad abrupt charge upon all the company to be silent, and observe the work of the Lord upon that prophane mocker, which they should presently behold; upon which immediately the prophane wretch sunk down and died beneath the table, but never returned to life again, to the great astonishment of all the company.

Another wonderful story they tell of him at the same time; the lord Ochiltry the captain, being both sons to the good lord Ochiltry, and Mr. Welch’s uncle in law, was indeed very civil to Mr. Welch, but being for a long time, through the multitude[15] of affairs, kept from visiting Mr. Welch in his chamber, as he was one day walking in the court, and espying Mr. Welch at his chamber window asked him kindly how he did, and if in any thing he could serve him. Mr. Welch answered him, He would earnestly entreat his lordship, being at that time to go to court, to petition king James in his name, that he might have liberty to preach the gospel; which my lord promised to do. Mr. Welch answered, my lord, both because you are my kinsman, and other reasons, I would earnestly entreat, and obtest you not to promise except you faithfully perform. My lord answered, He would faithfully perform his promise; and so went for London. But though at his first arrival he was really purposed to present the petition to the king, but when he found the king in such a rage against the godly ministers, that he durst not at that time present it, so he thought fit to delay it, and thereafter fully forgot it.

The first time that Mr. Welch saw his face after his return from court, he asked him what he had done with his petition. My lord answered he, had presented it to the king, but that the king was in so great a rage against the ministers at that time, he believed it had been forgotten, for he had gotten no answer. Nay said Mr. Welch to him, My lord you should not lye to God, and to me, for I know you never delivered it, though I warned you to take heed not to undertake it, except you would perform it; but because you have dealt so unfaithfully, remember God shall take from you both estate and honours, and give them to your neighbour in your own time: which accordingly came to pass, both his estate and honours were in his own time transmitted to James Stewart son to captain[16] James, who was indeed a cadet, but not the lineal heir of the family.

While he was detained prisoner in Edinburgh castle, his wife used for the most part to stay in his company, but upon a time fell into a longing to see her family in Ayr, to which with some difficulty he yielded; but when she was to take her journey, he strictly charged her not to take the ordinary way to her own house, when she came to Ayr, nor to pass by the bridge through the town, but to pass the river above the bridge, and so get the way to her own house, and not to come into the town, for, said he, before you come thither, you shall find the plague broken out in Ayr, which accordingly came to pass.

The plague was at that time very terrible, and he being necessarily separate from his people, it was to him the more grievous; but when the people of Ayr came to him to bemoan themselves, his answer was, that Hugh Kennedy, a godly gentleman in their town, should pray for them, and God should hear him. This counsel they accepted, and the gentleman convening a number of the honest citizens, prayed fervently for the town, as he was a mighty wrestler with God, and accordingly after that the plague decreased.

Now the time is come he must leave Scotland, and never to see it again, so upon the seventh of November 1606 in the morning, he with his neighbours took ship at Leith, and though it was but two o’clock in the morning, many were waiting on with their afflicted families, to bid them farewell. After prayer, they sung the xxiii psalm, and so set sail for the south of France, and landed in the river of Bourdeaux. Within fourteen weeks after his arrival, such was the Lord’s blessing[17] upon his diligence, he was able to preach in French, and accordingly was speedily called to the ministry, first in one village, then in another; one of them was Nerac, and thereafter settled in Saint Jean d’ Angely, a considerable walled town, and there he continued the rest of the time he sojourned in France, which was about sixteen years. When he began to preach, it was observed by some of his hearers, that while he continued in the doctrinal part of his sermon, he spoke very correct French, but when he came to his application and when his affections kindled, his fervour made him sometimes neglect the accuracy of the French construction: but there were godly young men who admonished him of this, which he took in very good part, so for preventing mistakes of that kind, he desired the young gentlemen, when they perceived him beginning to decline, to give him a sign, and the sign was, that they were both to stand up upon their feet, and thereafter he was more exact in his expression through his whole sermon; so desirous was he, not only to deliver good matter, but to recommend it in the neat expression.

There were many times persons of great quality in his auditory, before whom he was just as bold as ever he had been in a Scots village; which moved Mr. Boyd of Trochrig once to ask him, (after he had preached before the university of Samure with such boldness and authority, as if he had been before the meanest congregation) how he could be so confident among strangers, and persons of such quality! to which he answered, That he was so filled with the dread of God, he had no apprehension from man at all; and this answer, said Mr. Boyd, did not remove my admiration, but rather increased it.

There was in his house amongst many others, who tabled with him for good education, a young gentleman of great quality, and suitable expectations, and this was the heir of the lord Ochiltry, who was captain of the castle of Edinburgh. This young nobleman, after he had gained very much upon Mr. Welch’s affections, fell sick of a grievous sickness, and after he had been long wasted with it, closed his eyes, and expired as dying men used to do, so to the apprehension and sense of all spectators, he was no more but a carcase, and was therefore taken out of his bed, and laid upon a pallat on the floor, that his body might be the more conveniently dressed, as dead bodies used to be. This was to Mr. Welch a very great grief, and therefore he stayed with the young man’s dead body full three hours, lamenting over him with great tenderness. After twelve hours, the friends brought in a coffin, whereunto they desired the corps to be put, as the custom is: but Mr. Welch desired, that for the satisfaction of his affections, they would forbear the youth for a time, which they granted, and returned not till twenty four hours, after his death, were expired; then they returned, with great importunity the corps might be coffined, that it might be speedily buried, the weather being extremely hot; yet he persisted in his request, earnestly begging them to excuse him for once more; so they left the youth upon his pallat for full thirty six hours: but even after all that, though he was urged, not only with great earnestness, but displeasure, they were constrained to forbear for twelve hours yet more; and after forty eight hours were past, Mr. Welch was still where he was, and then his friends perceived that he believed the young man was not really dead, but under some[19] apoplectic fit, and therefore proponed to him for his satisfaction, that trial should be made upon his body by doctors and chirurgeons, if possibly any spark of life might be found in him, and with this he was content: so the physicians are set on work, who pinched him with pincers in the fleshy parts of his body, and twisted a bow string about his head with great force, but no sign of life appearing in him, so the physicians pronounced him stark dead, and then there was no more delay to be desired; yet Mr. Welch begged of them once more, that they would but step into the next room for an hour or two, and leave him with the dead youth, and this they granted: Then Mr. Welch fell down before the pallat, and cried to the Lord with all his might, for the last time and sometimes looked upon the dead body, continuing in wrestling with the Lord till at length the dead youth opened his eyes, and cried out to Mr. Welch whom he distinctly knew, O Sir, I am all whole, but my head and legs: and these were the places they had sore hurt, with their pinching.

When Mr. Welch perceived this, he called upon his friends, and shewed them the dead young man restored to life again, to their great astonishment. And this young nobleman, though he lost the estate of Ochiltry, lived to acquire a great estate in Ireland, and was lord Castlestewart, and a man of such excellent parts, that he was courted by the earl of Stafford to be a counsellor in Ireland, which he refused to be, and then he engaged, and continued for all his life, not only in honour and power, but in the profession and practice of godliness, to the great comfort of the country where he lived. This story the nobleman communicated to his friends in Ireland, and from them I had it.

While Mr. Welch was minister in one of these French villages, upon an evening a certain popish friar travelling through the country, because he could not find lodging in the whole village, addressed himself to Mr. Welch’s house for one night. The servants acquainted their master and he was content to receive this guest. The family had supped before he came, and so the servants convoyed the friar to his chamber, and after they had made his supper, they left him to his rest. There was but a timber partition betwixt him and Mr. Welch, and after the friar had slept his first sleep, he was surprized with the hearing of a silent, but constant whispering noise, at which he wondered very much, and was not a little troubled with it.

The next morning he walked in the fields, where he chanced to meet with a country man, who saluting him because of his habit, asked him where he lodged that night? The friar answered he had lodged with the hugenot minister. Then the country man asked him what entertainment he had? The friar answered, Very bad; for, said he, I always held there were devils haunting these ministers houses, and I am persuaded there was one with me this night, for I heard a continual whisper all the night over, which I believe was no other thing, than the minister and the devil conversing together. The country man told him, he was much mistaken, and that it was nothing else, but the minister at his night prayer. O, said the friar, does the minister pray any? Yes, more than any man in France, answered the country man, and if you please to stay another night with him you may be satisfied. The friar got home to Mr. Welch’s house, and pretending indisposition, entreated another night’s lodging, which was granted him.

Before dinner, Mr. Welch come from his chamber, and made his family exercise, according to his custom. And first he sung a psalm, then read a portion of scripture, and discoursed upon it, thereafter he prayed with great fervour, as his custom was, to all which the friar was an astonished witness. After the exercise they went to dinner, where the friar was very civilly entertained, Mr. Welch, forbearing all questions and dispute with him for the time; when the evening came, Mr. Welch made his exercise as he had done in the morning, which occasioned yet more wondering in the friar, and after supper to bed they all went; but the friar longed much to know what the night whisper was, and in that he was soon satisfied, for after Mr. Welch’s first sleep, the noise began, and then the friar resolved to be sure what it was, so he crept silently to Mr. Welch’s chamber-door, and there he heard not only the sound, but the words distinctly, and communications betwixt man and God, and such as he knew not had been in the world. Upon the next morning, as soon as Mr. Welch was ready, the friar went to him, and told him, that he had been bred in ignorance, and lived in darkness all his time, but now he was resolved to adventure his soul with Mr. Welch, and thereupon declared himself Protestant: Mr. Welch welcomed him and encouraged him, and he continued a constant protestant to his dying day. This story I had from a godly minister, who was bred in Mr. Welch’s house, when in France.

When Lewis XIII. king of France, made war upon the Protestants there, because of their religion, the city of St. Jean d’ Angely, was by him and his royal army besieged, and brought into extreme danger, Mr. Welch was minister in the[22] town, and mightily encouraged the citizens to hold out, assuring them, God should deliver them. In the time of the siege a cannon ball pierced the bed where he was lying, upon which he got up, but would not leave the room, till he had by solemn prayer acknowledged his deliverance. During the siege, the townsmen made stout defence, until one of the king’s gunners planted a great gun so conveniently upon a rising ground, that therewith he could command the whole wall, upon which the townsmen made their greatest defence. Upon this they were constrained to forsake the whole wall in great terror, and though they had several guns planted upon the wall, no man durst undertake to manage them. This being told Mr. Welch with great affrightment, he notwithstanding encouraged them still to hold out, and running to the wall himself, found the cannonier, who was a Burgundian, near the wall, him he entreated to mount the wall, promising to assist him in person, so to the wall they got. The cannonier told Mr. Welch, that either they behoved to dismount the gun upon the rising ground, or else they were surely lost; Mr. Welch desired him to aim well, and he should serve him, and God would help him; so the gunner falls a scouring his piece, and Mr. Welch runs to the powder to fetch him a charge; but as soon as he was returning, the king’s gunner fired his piece, which carried both the powder and ladle out of Mr. Welch’s hands, which yet did not discourage him, for having left the ladle, he filled his hat with powder, wherewith the gunner loaded his piece, and dismounted the king’s gun at the first shot, so the citizens returned to their post of defence.

This discouraged the king so, that he sent to the citizens to offer them fair conditions, which were,[23] That they should enjoy the liberty of their religion, their civil privileges, and their walls should not be demolished: only the king desired for his honours that he might enter the city with his servants in a friendly manner. This the city thought fit to grant, and the king with a few more entered the city for a short time.

But within a short time thereafter the war was renewed, and then Mr. Welch told the inhabitants of the city, that now their cup was full, and they should no more escape; which accordingly came to pass, for the king took the town, and as soon as ever it fell into his hand, he commanded Vitry, the captain of his guard, to enter the town, and preserve his minister from all danger; and then were horses and waggons provided for Mr. Welch, to remove him and his family for Rochel, where he remained till he obtained liberty to come to England, and his friends made hard suit, that he might be permitted to return to Scotland; because the physicians declared there was no other way to preserve his life, but by the freedom he might have in his native air. But to this king James would never yield, protesting he should never be able to establish his beloved bishops in Scotland, if Mr. Welch were permitted to return thither; so he languished at London a considerable time, his disease was judged by some to have a tendency to a sort of leprosy; physicians say he had been poisoned; a langour he had, together with a great weakness in his knees, caused by his continual kneeling at prayer: by which it came to pass, that though he was able to move his knees, and to walk, yet he was wholly insensible in them, and the flesh became hard like a sort of horn. But when in the time of his weak[24]ness, he was desired to remit somewhat of his excessive painfulness, his answer was, He had his life of God, and therefore it should be spent for him.

His friends importuned king James very much, that if he might not return to Scotland, at least he might have liberty to preach at London, which king James would never grant, till he heard all hopes of life were past, and then he allowed him liberty to preach, not fearing his activity.

Then as soon as ever he heard he might preach, he greedily embraced this liberty, and having access to a lecturer’s pulpit, he went and preached both long and fervently: which was the last performance of his life; for after he had ended his sermon, he returned to his chamber, and within two hours quietly and without pain, he resigned his spirit into his Maker’s hands, and was buried near Mr. Deering, the famous English divine, after he had lived little more than fifty-two years.

FINIS

THE

LIFE

AND

PROPHECIES,

OF

ALEXANDER PEDEN

GLASGOW;

PRINTED FOR THE BOOKSELLERS.

That most excellent minister of the gospel, and faithful defender of the Presbyterian Religion, Mr. Alexander Peden, was born in the parish of Sorn, near Ayr. After his course at the College, he was sometime school-master, precentor, and session-clerk to Mr. John Guthrie, minister of the gospel at Tarbolton. When he was about to enter on the ministry, a young woman fell with child, in adultery, to a servant in the house where she stayed; when she found herself to be so, she told the father thereof, who said, I’ll run for it, and go to Ireland, father it upon Mr. Peden, he has more to help you to bring it up (he having a small heritage) than I have. The same day that he was to get his licence, she came in before the Presbytery and said, I hear you are to licence Mr. Peden, to be a minister; but do it not, for I am with child to him. He being without at the time, was called in by the moderator; and being questioned about it, he said, I[3] am utterly surprised, I cannot speak; but let none entertain an ill thought of me, for I am utterly free of it, and God will vindicate me in his own time and way. He went home, and walked at a water-side upwards of 24 hours, and would neither eat nor drink, but said, I have got what I was seeking, and I will be vindicated, and that poor unhappy lass will pay dear for it in her life, and will make a dismal end; and for this surfeit of grief that she hath given me, there shall never one of her sex come into my bosom; and, accordingly he never married. There are various reports of the way that he was vindicated; some say, the time she was in child-birth, Mr. Guthrie charged her to give account who was the father of that child, and discharged the women to be helpful to her, until she did it: some say, that she confessed: others, that she remained obstinate. Some of the people when I made enquiry about it in that country-side, affirmed, that the Presbytery had been at all pains about it, and could get no satisfaction, they appointed Mr. Guthrie to give a full relation of the whole before the congregation, which he did; and the same day the father of the child being present, when he heard Mr. Guthrie begin to speak, he stood up, and desired him to halt, and said, I am the father of that child, and I desired her to fa[4]ther it on Mr. Peden, which has been a great trouble of conscience to me; and I could not get rest till I came home to declare it. However it is certain, that after she was married, every thing went cross to them; and they went from place to place, and were reduced to great poverty. At last she came to that same spot of ground where he stayed upwards of 24 hours, and made away with herself!

2. After this he was three years settled minister at New Glenluce in Galloway; and when he was obliged, by the violence and tyranny of that time, to leave that parish, he lectured upon Acts xx. 17. to the end, and preached upon the 31st. verse in the forenoon, ‘Therefore watch, and remember that for the space of three years I ceased not to warn every one, night and day, with tears:’ Asserting that he had declared the whole counsel of God, and had kept nothing back and protested that he was free of the blood of all souls. And, in the afternoon he preached on the 32d verse, ‘And now, brethren, I commend you to God, and to the word of his grace, which is able to build you up, and to give you an inheritance among all them that are sanctified.’ Which was a weeping day in that kirk; the greatest part could not contain themselves. He many times requested them to be silent; but they sor[5]rowed most of all when he told them that they should never see his face in that pulpit again. He continued until night; and when he closed the pulpit-door he knocked hard upon it three times with his Bible, saying three times over, I arrest in my Master’s name, that never one enter there, but such as come in by the door, as I did. Accordingly, neither curate nor indulged minister ever entered that pulpit, until after the revolution, that a Presbyterian minister opened it.

3. After this he joined with that honest and zealous handful in the year 1666, that was broken at Pentland-hills, and came the length of Clyde with them, where he had a melancholy view of their end, and parted with them there. James Cubison, of Paluchbeaties, my informer, to whom he told this, he said to him, ‘Sir, you did well that parted with them, seeing you was persuaded they would fall and flee before the enemy.—Glory glory to God, that he sent me not to hell immediately! for I should have stayed with them though I should have been cut all in pieces.’

4. That night the Lord’s people fell, and fled before the enemy at Pentland-hills, he was in a friend’s house in Carrick, sixty miles from Edinburgh; his landlord seeing him mightily troubled enquired how it was with him; he said, ‘To-morrow I will speak with you,’ and desired some can[6]dle. That night he went to bed. The next morning calling early to his landlord, said, ‘I have sad news to tell you, our friends that were together in arms, appearing for Christ’s interest, are now broken, killed, taken, and fled every man.’—the truth of which was fully verified in about 48 hours thereafter.

5. After this, in June 1673, he was taken by Major Cockburn, in the house of Hugh Ferguson, of Knockdow, in Carrick, who constrained him to tarry all night. Mr. Peden told him that it would be a dear night to them both. Accordingly they were both carried prisoners to Edinburgh, Hugh Ferguson was fined in a thousand merks, for resetting, harbouring, and conversing with him. The Council ordered fifty pounds sterling to be paid to the Major out of the fines, and ordained him to divide twenty-five pounds sterling among the party that apprehended him. Some time after examination he was sent prisoner to the Bass, where, and at Edinburgh, he remained until December, 1668, that he was banished.