ANTE-NICENE

CHRISTIAN LIBRARY:

TRANSLATIONS OF

THE WRITINGS OF THE FATHERS

DOWN TO A.D. 325.

EDITED BY THE

REV. ALEXANDER ROBERTS, D.D.,

AND

JAMES DONALDSON, LL.D.

VOL. XII.

CLEMENT OF ALEXANDRIA.

VOL. II.

EDINBURGH:

T. & T. CLARK, 38, GEORGE STREET.

MDCCCLXIX.

MURRAY AND GIBB, EDINBURGH,

PRINTERS TO HER MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE

TRANSLATED BY

THE REV. WILLIAM WILSON, M.A.,

MUSSELBURGH.

VOLUME II.

EDINBURGH:

T. & T. CLARK, 38, GEORGE STREET.

LONDON: HAMILTON & CO. DUBLIN: JOHN ROBERTSON & CO.

MDCCCLXIX.

| THE MISCELLANIES. | ||

|---|---|---|

| BOOK II. | ||

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| 1. | Introductory, | 1 |

| 2. | The Knowledge of God can be attained only through Faith, | 3 |

| 3. | Faith not a product of Nature, | 6 |

| 4. | Faith the foundation of all Knowledge, | 8 |

| 5. | He proves by several examples that the Greeks drew from the Sacred Writers, | 12 |

| 6. | The Excellence and Utility of Faith, | 16 |

| 7. | The Utility of Fear. Objections Answered, | 20 |

| 8. | The Vagaries of Basilides and Valentinus as to Fear being the Cause of Things, | 22 |

| 9. | The Connection of the Christian Virtues, | 26 |

| 10. | To what the Philosopher applies himself, | 29 |

| 11. | The Knowledge which comes through Faith the Surest of All, | 30 |

| 12. | Twofold Faith, | 33 |

| 13. | On First and Second Repentance, | 35 |

| 14. | How a Thing may be Involuntary, | 37 |

| 15. | On the different kinds of Voluntary Actions, and the Sins thence proceeding, | 38 |

| 16. | How we are to explain the passages of Scripture which ascribe to God Human Affections, | 43 |

| 17. | On the various kinds of Knowledge, | 45 |

| 18. | The Mosaic Law the fountain of all Ethics, and the source from which the Greeks drew theirs, | 47 |

| 19. | The true Gnostic is an imitator of God, especially in Beneficence, | 57 |

| 20. | The true Gnostic exercises Patience and Self-restraint, | 60 |

| 21. | Opinions of various Philosophers on the Chief Good, | 71 |

| 22. | Plato’s Opinion, that the Chief Good consists in assimilation to God, and its agreement with Scripture, | 74 |

| 23. | On Marriage, | 78 |

| BOOK III. | ||

| 1. | Basilidis Sententiam de Continentia et Nuptiis refutat, | 84 |

| 2. | Carpocratis et Epiphanis Sententiam de Feminarum Communitate refutat, | 86 |

| 3. | Quatenus Plato aliique e veteribus præiverint Marcionitis aliisque Hæreticis, qui a Nuptiis ideo abstinent quia Creaturam malam existimant et nasci Homines in Pœnam opinantur, | 89 |

| 4. | Quibus prætextibus utantur Hæretici ad omnis generis licentiam et libidinem exercendam, | 95 |

| 5. | Duo genera Hæreticorum notat: prius illorum qui omnia omnibus licere pronuntiant, quos refutat, | 102 |

| 6. | Secundum genus Hæreticorum aggreditur, illorum scilicet qui ex impia de deo omnium conditore Sententia, Continentiam exercent, | 105 |

| 7. | Qua in re Christianorum Continentia eam quam sibi vindicant Philosophi antecellat, | 110 |

| 8. | Loca S. Scripturæ ab Hæreticis in vituperium Matrimonii adducta explicat; et primo verba Apostoli Rom. vi. 14, ab Hæreticorum perversa interpretatione vindicat, | 112 |

| 9. | Dictum Christi ad Salomen exponit, quod tanquam in vituperium Nuptiarum prolatum Hæretici allegabant, | 113 |

| 10. | Verba Christi Matt. xviii. 20, mystice exponit, | 116 |

| 11. | Legis et Christi mandatum de non Concupiscendo exponit, | 117 |

| 12. | Verba Apostoli 1 Cor. vii. 5, 39, 40, aliaque S. Scripturæ loca eodem spectantia explicat, | 121 |

| 13. | Julii Cassiani Hæretici verbis respondet; item loco quem ex Evangelio Apocrypho idem adduxerat, | 128 |

| 14. | 2 Cor. xi. 3, et Eph. iv. 24, exponit, | 129 |

| 15. | 1 Cor. vii. 1; Luc. xiv. 26; Isa. lvi. 2, 3, explicat, | 130 |

| 16. | Jer. xx. 14; Job xiv. 3; Ps. l. 5; 1 Cor. ix. 27, exponit, | 132 |

| 17. | Qui Nuptias et Generationem malas asserunt, ii et dei Creationem et ipsam evangelii Dispensationem vituperant, | 133 |

| 18. | Duas extremas Opiniones esse vitandas: primam illorum qui Creatoris odio a Nuptiis abstinent; alteram illorum qui hinc occasionem arripiunt nefariis libidinibus indulgendi, | 135 |

| BOOK IV. | ||

| 1. | Order of Contents, | 139 |

| 2. | The meaning of the name Stromata [Miscellanies], | 140 |

| 3. | The true Excellence of Man, | 142 |

| 4. | The Praises of Martyrdom, | 145 |

| 5. | On Contempt for Pain, Poverty, and other external things, | 148 |

| 6. | Some points in the Beatitudes, | 150 |

| 7. | The Blessedness of the Martyr, | 158 |

| 8. | Women as well as Men, Slaves as well as Freemen, Candidates for the Martyr’s Crown, | 165 |

| 9. | Christ’s Sayings respecting Martyrdom, | 170 |

| 10. | Those who offered themselves for Martyrdom reproved, | 173 |

| 11. | The objection, Why do you suffer if God cares for you, answered, | 174 |

| 12. | Basilides’ idea of Martyrdom refuted, | 175 |

| 13. | Valentinian’s Vagaries about the Abolition of Death refuted, | 179 |

| 14. | The Love of All, even of our Enemies, | 182 |

| 15. | On avoiding Offence, | 183 |

| 16. | Passages of Scripture respecting the Constancy, Patience, and Love of the Martyrs, | 184 |

| 17. | Passages from Clement’s Epistle to the Corinthians on Martyrdom, | 187 |

| 18. | On Love, and the repressing of our Desires, | 190 |

| 19. | Women as well as Men capable of Perfection, | 193 |

| 20. | A Good Wife, | 196 |

| 21. | Description of the Perfect Man, or Gnostic, | 199 |

| 22. | The true Gnostic does Good, not from fear of Punishment or hope of Reward, but only for the sake of Good itself, | 202 |

| 23. | The same subject continued, | 207 |

| 24. | The reason and end of Divine Punishments, | 210 |

| 25. | True Perfection consists in the Knowledge and Love of God, | 212 |

| 26. | How the Perfect Man treats the Body and the Things of the World, | 215 |

| BOOK V. | ||

| 1. | On Faith, | 220 |

| 2. | On Hope, | 228 |

| 3. | The objects of Faith and Hope perceived by the Mind alone, | 229 |

| 4. | Divine Things wrapped up in Figures both in the Sacred and in Heathen Writers, | 232 |

| 5. | On the Symbols of Pythagoras, | 236 |

| 6. | The Mystic Meaning of the Tabernacle and its Furniture, | 240 |

| 7. | The Egyptian Symbols and Enigmas of Sacred Things, | 245 |

| 8. | The use of the Symbolic Style by Poets and Philosophers, | 247 |

| 9. | Reasons for veiling the Truth in Symbols, | 254 |

| 10. | The opinion of the Apostles on veiling the Mysteries of the Faith, | 257 |

| 11. | Abstraction from Material Things necessary in order to attain to the true Knowledge of God, | 261 |

| 12. | God cannot be embraced in Words or by the Mind, | 267 |

| 13. | The Knowledge of God a Divine Gift, according to the Philosophers, | 270 |

| 14. | Greek Plagiarisms from the Hebrews, | 274 |

| BOOK VI. | ||

| 1. | Plan, | 302 |

| 2. | The subject of Plagiarisms resumed. The Greeks plagiarized from one another, | 304 |

| 3. | Plagiarism by the Greeks of the Miracles related in the Sacred Books of the Hebrews, | 319 |

| 4. | The Greeks drew many of their Philosophical Tenets from the Egyptian and Indian Gymnosophists, | 323 |

| 5. | The Greeks had some Knowledge of the true God, | 326 |

| 6. | The Gospel was preached to Jews and Gentiles in Hades, | 328 |

| 7. | What true Philosophy is, and whence so called, | 335 |

| 8. | Philosophy is Knowledge given by God, | 339 |

| 9. | The Gnostic free of all Perturbations of the Soul, | 344 |

| 10. | The Gnostic avails himself of the help of all Human Knowledge, | 349 |

| 11. | The Mystical Meanings in the proportions of Numbers, Geometrical Ratios, and Music, | 352 |

| 12. | Human Nature possesses an adaptation for Perfection; the Gnostic alone attains it, | 359 |

| 13. | Degrees of Glory in Heaven corresponding with the Dignities of the Church below, | 365 |

| 14. | Degrees of Glory in Heaven, | 366 |

| 15. | Different Degrees of Knowledge, | 371 |

| 16. | Gnostic Exposition of the Decalogue, | 383 |

| 17. | Philosophy conveys only an imperfect Knowledge of God, | 393 |

| 18. | The use of Philosophy to the Gnostic, | 401 |

| BOOK VII. | ||

| 1. | The Gnostic a true Worshipper of God, and unjustly calumniated by Unbelievers as an Atheist, | 406 |

| 2. | The Son the Ruler and Saviour of All, | 409 |

| 3. | The Gnostic aims at the nearest Likeness possible to God and His Son, | 414 |

| 4. | The Heathens made Gods like themselves, whence springs all Superstition, | 421 |

| 5. | The Holy Soul a more excellent Temple than any Edifice built by Man, | 424 |

| 6. | Prayers and Praise from a Pure Mind, ceaselessly offered, far better than Sacrifices, | 426 |

| 7. | What sort of Prayer the Gnostic employs, and how it is heard by God, | 431 |

| 8. | The Gnostic so addicted to Truth as not to need to use an Oath, | 442 |

| 9. | Those who teach others, ought to excel in Virtues, | 444 |

| 10. | Steps to Perfection, | 446 |

| 11. | Description of the Gnostic’s Life, | 449 |

| 12. | The true Gnostic is Beneficent, Continent, and despises Worldly Things, | 455 |

| 13. | Description of the Gnostic continued, | 466 |

| 14. | Description of the Gnostic furnished by an Exposition of 1 Cor. vi. 1, etc., | 468 |

| 15. | The objection to join the Church on account of the diversity of Heresies answered, | 472 |

| 16. | Scripture the Criterion by which Truth and Heresy are distinguished, | 476 |

| 17. | The Tradition of the Church prior to that of the Heresies, | 485 |

| 18. | The Distinction between Clean and Unclean Animals in the Law symbolical of the Distinction between the Church, and Jews, and Heretics, | 488 |

| BOOK VIII. | ||

| 1. | The object of Philosophical and Theological Inquiry—the Discovery of Truth, | 490 |

| 2. | The necessity of Perspicuous Definition, | 491 |

| 3. | Demonstration defined, | 492 |

| 4. | To prevent Ambiguity, we must begin with clear Definition, | 496 |

| 5. | Application of Demonstration to Sceptical Suspense of Judgment, | 500 |

| 6. | Definitions, Genera, and Species, | 502 |

| 7. | On the Causes of Doubt or Assent, | 505 |

| 8. | The Method of classifying Things and Names, | 506 |

| 9. | On the different kinds of Causes, | 508 |

| Indexes—Index of Texts, | 515 | |

| Index of Subjects, | 525 | |

[1]

THE MISCELLANIES.

As Scripture has called the Greeks pilferers of the Barbarian[1] philosophy, it will next have to be considered how this may be briefly demonstrated. For we shall not only show that they have imitated and copied the marvels recorded in our books; but we shall prove, besides, that they have plagiarized and falsified (our writings being, as we have shown, older) the chief dogmas they hold, both on faith and knowledge and science, and hope and love, and also on repentance and temperance and the fear of God,—a whole swarm, verily, of the virtues of truth.

Whatever the explication necessary on the point in hand shall demand, shall be embraced, and especially what is occult in the Barbarian philosophy, the department of symbol and enigma; which those who have subjected the teaching of the ancients to systematic philosophic study have affected, as being in the highest degree serviceable, nay, absolutely necessary to the knowledge of truth. In addition, it will in my opinion form an appropriate sequel to defend those tenets, on account of which the Greeks assail us, making use of a few scriptures, if perchance the Jew also may listen and be able quietly to turn from what he has believed to Him on[2] whom he has not believed. The ingenuous among the philosophers will then with propriety be taken up in a friendly exposure both of their life and of the discovery of new dogmas, not in the way of our avenging ourselves on our detractors (for that is far from being the case with those who have learned to bless those who curse, even though they needlessly discharge on us words of blasphemy), but with a view to their conversion; if by any means these adepts in wisdom may feel ashamed, being brought to their senses by barbarian demonstration; so as to be able, although late, to see clearly of what sort are the intellectual acquisitions for which they make pilgrimages over the seas. Those they have stolen are to be pointed out, that we may thereby pull down their conceit; and of those on the discovery of which through investigation they plume themselves, the refutation will be furnished. By consequence, also we must treat of what is called the curriculum of study—how far it is serviceable;[2] and of astrology, and mathematics, and magic, and sorcery. For all the Greeks boast of these as the highest sciences. “He who reproves boldly is a peacemaker.”[3] We have often said already that we have neither practised nor do we study the expressing ourselves in pure Greek; for this suits those who seduce the multitude from the truth. But true philosophic demonstration will contribute to the profit not of the listeners’ tongues, but of their minds. And, in my opinion, he who is solicitous about truth ought not to frame his language with artfulness and care, but only to try to express his meaning as he best can. For those who are particular about words, and devote their time to them, miss the things. It is a feat fit for the gardener to pluck without injury the rose that is growing among the thorns; and for the craftsman to find out the pearl buried in the oyster’s flesh. And they say that fowls have flesh of the most agreeable quality, when, through not being supplied with abundance of food, they pick their sustenance with difficulty, scraping with their feet. If any one, then, speculating on what is similar,[3] wants to arrive[4] at the truth [that is] in the numerous Greek plausibilities, like the real face beneath masks, he will hunt it out with much pains. For the power that appeared in the vision to Hermas said, “Whatever may be revealed to you, shall be revealed.”[5]

“Be not elated on account of thy wisdom,” say the Proverbs. “In all thy ways acknowledge her, that she may direct thy ways, and that thy foot may not stumble.” By these remarks he means to show that our deeds ought to be conformable to reason, and to manifest further that we ought to select and possess what is useful out of all culture. Now the ways of wisdom are various that lead right to the way of truth. Faith is the way. “Thy foot shall not stumble” is said with reference to some who seem to oppose the one divine administration of Providence. Whence it is added, “Be not wise in thine own eyes,” according to the impious ideas which revolt against the administration of God. “But fear God,” who alone is powerful. Whence it follows as a consequence that we are not to oppose God. The sequel especially teaches clearly, that “the fear of God is departure from evil;” for it is said, “and depart from all evil.” Such is the discipline of wisdom (“for whom the Lord loveth He chastens”[6]), causing pain in order to produce understanding, and restoring to peace and immortality. Accordingly, the Barbarian philosophy, which we follow, is in reality perfect and true. And so it is said in the book of Wisdom: “For He hath given me the unerring knowledge of things that exist, to know the constitution of the world,” and so forth, down to “and the virtues of roots.” Among all these he[4] comprehends natural science, which treats of all the phenomena in the world of sense. And in continuation, he alludes also to intellectual objects in what he subjoins: “And what is hidden or manifest I know; for Wisdom, the artificer of all things, taught me.”[7] You have, in brief, the professed aim of our philosophy; and the learning of these branches, when pursued with right course of conduct leads through Wisdom, the artificer of all things, to the Ruler of all,—a Being difficult to grasp and apprehend, ever receding and withdrawing from him who pursues. But He who is far off has—oh ineffable marvel!—come very near. “I am a God that draws near,” says the Lord. He is in essence remote; “for how is it that what is begotten can have approached the Unbegotten?” But He is very near in virtue of that power which holds all things in its embrace. “Shall one do aught in secret, and I see him not?”[8] For the power of God is always present, in contact with us, in the exercise of inspection, of beneficence, of instruction. Whence Moses, persuaded that God is not to be known by human wisdom, said, “Show me Thy glory;”[9] and into the thick darkness where God’s voice was, pressed to enter—that is, into the inaccessible and invisible ideas respecting Existence. For God is not in darkness or in place, but above both space and time, and qualities of objects. Wherefore neither is He at any time in a part, either as containing or as contained, either by limitation or by section. “For what house will ye build to me?” saith the Lord.[10] Nay, He has not even built one for Himself, since He cannot be contained. And though heaven be called His throne, not even thus is He contained, but He rests delighted in the creation.

It is clear, then, that the truth has been hidden from us; and if that has been already shown by one example, we shall establish it a little after by several more. How entirely worthy of approbation are they who are both willing to learn, and able, according to Solomon, “to know wisdom and instruction, and to perceive the words of wisdom, to receive[5] knotty words, and to perceive true righteousness,” there being another [righteousness as well], not according to the truth, taught by the Greek laws, and by the rest of the philosophers. “And to direct judgments,” it is said—not those of the bench, but he means that we must preserve sound and free of error the judicial faculty which is within us—“That I may give subtlety to the simple, to the young man sense and understanding.”[11] “For the wise man,” who has been persuaded to obey the commandments, “having heard these things, will become wiser” by knowledge; and “the intelligent man will acquire rule, and will understand a parable and a dark word, the sayings and enigmas of the wise.”[12] For it is not spurious words which those inspired by God and those who are gained over by them adduce, nor is it snares in which the most of the sophists entangle the young, spending their time on nought true. But those who possess the Holy Spirit “search the deep things of God,”[13]—that is, grasp the secret that is in the prophecies. “To impart of holy things to the dogs” is forbidden, so long as they remain beasts. For never ought those who are envious and perturbed, and still infidel in conduct, shameless in barking at investigation, to dip in the divine and clear stream of the living water. “Let not the waters of thy fountain overflow, and let thy waters spread over thine own streets.”[14] For it is not many who understand such things as they fall in with; or know them even after learning them, though they think they do, according to the worthy Heraclitus. Does not even he seem to thee to censure those who believe not? “Now my just one shall live by faith,”[15] the prophet said. And another prophet also says, “Except ye believe, neither shall ye understand.”[16] For how ever could the soul admit the transcendental contemplation of such themes, while unbelief respecting what was to be learned struggled within? But faith, which the Greeks disparage, deeming it futile and barbarous, is a voluntary preconception,[17] the assent of piety—“the subject of things hoped for, the[6] evidence of things not seen,” according to the divine apostle. “For hereby,” pre-eminently, “the elders obtained a good report. But without faith it is impossible to please God.”[18] Others have defined faith to be a uniting assent to an unseen object, as certainly the proof of an unknown thing is an evident assent. If then it be choice, being desirous of something, the desire is in this instance intellectual. And since choice is the beginning of action, faith is discovered to be the beginning of action, being the foundation of rational choice in the case of any one who exhibits to himself the previous demonstration through faith. Voluntarily to follow what is useful, is the first principle of understanding. Unswerving choice, then, gives considerable momentum in the direction of knowledge. The exercise of faith directly becomes knowledge, reposing on a sure foundation. Knowledge, accordingly, is defined by the sons of the philosophers as a habit, which cannot be overthrown by reason. Is there any other true condition such as this, except piety, of which alone the Word is teacher?[19] I think not. Theophrastus says that sensation is the root of faith. For from it the rudimentary principles extend to the reason that is in us, and the understanding. He who believeth then the divine Scriptures with sure judgment, receives in the voice of God, who bestowed the Scripture, a demonstration that cannot be impugned. Faith, then, is not established by demonstration. “Blessed therefore those who, not having seen, yet have believed.”[20] The Siren’s songs exhibiting a power above human, fascinated those that came near, conciliating them, almost against their will, to the reception of what was said.

Now the followers of Basilides regard faith as natural, as[7] they also refer it to choice, [representing it] as finding ideas by intellectual comprehension without demonstration; while the followers of Valentinus assign faith to us, the simple, but will have it that knowledge springs up in their own selves (who are saved by nature) through the advantage of a germ of superior excellence, saying that it is as far removed from faith as[21] the spiritual is from the animal. Further, the followers of Basilides say that faith as well as choice is proper according to every interval; and that in consequence of the supramundane selection mundane faith accompanies all nature, and that the free gift of faith is conformable to the hope of each. Faith, then, is no longer the direct result of free choice, if it is a natural advantage.

Nor will he who has not believed, not being the author [of his unbelief], meet with a due recompense; and he that has believed is not the cause of his belief]. And the entire peculiarity and difference of belief and unbelief will not fall under either praise or censure, if we reflect rightly, since there attaches to it the antecedent natural necessity proceeding from the Almighty. And if we are pulled like inanimate things by the puppet-strings of natural powers, willingness[22] and unwillingness, and impulse, which is the antecedent of both, are mere redundancies. And for my part, I am utterly incapable of conceiving such an animal as has its appetencies, which are moved by external causes, under the dominion of necessity. And what place is there any longer for the repentance of him who was once an unbeliever, through which comes forgiveness of sins? So that neither is baptism rational, nor the blessed seal,[23] nor the Son, nor the Father. But God, as I think, turns out to be the distribution to men of natural powers, which has not as the foundation of salvation voluntary faith.

[8]

But we, who have heard by the Scriptures that self-determining choice and refusal have been given by the Lord to men, rest in the infallible criterion of faith, manifesting a willing spirit, since we have chosen life and believe God through His voice. And he who has believed the Word knows the matter to be true; for the Word is truth. But he who has disbelieved Him that speaks, has disbelieved God.

“By faith we understand that the worlds were framed by the word of God, so that what is seen was not made of things which appear,” says the apostle. “By faith Abel offered to God a fuller sacrifice than Cain, by which he received testimony that he was righteous, God giving testimony to him respecting his gifts; and by it he, being dead, yet speaketh,” and so forth, down to “than enjoy the pleasures of sin for a season.”[24] Faith having, therefore, justified these before the law, made them heirs of the divine promise. Why then should I review and adduce any further testimonies of faith from the history in our hands? “For the time would fail me were I to tell of Gideon, Barak, Samson, Jephtha, David, and Samuel, and the prophets,” and what follows.[25] Now, inasmuch as there are four things in which the truth resides—Sensation, Understanding, Knowledge, Opinion,—intellectual apprehension is first in the order of nature; but in our case, and in relation to ourselves, Sensation is first, and of Sensation and Understanding the essence of Knowledge is formed; and evidence is common to Understanding and Sensation. Well, Sensation is the ladder to Knowledge; while Faith, advancing over the pathway of the objects of sense, leaves Opinion behind, and speeds to things free of deception, and reposes in the truth.

Should one say that Knowledge is founded on demonstration by a process of reasoning, let him hear that first principles are[9] incapable of demonstration; for they are known neither by art nor sagacity. For the latter is conversant about objects that are susceptible of change, while the former is practical solely, and not theoretical.[26] Hence it is thought that the first cause of the universe can be apprehended by faith alone. For all knowledge is capable of being taught; and what is capable of being taught is founded on what is known before. But the first cause of the universe was not previously known to the Greeks; neither, accordingly, to Thales, who came to the conclusion that water was the first cause; nor to the other natural philosophers who succeeded him, since it was Anaxagoras who was the first who assigned to Mind the supremacy over material things. But not even he preserved the dignity suited to the efficient cause, describing as he did certain silly vortices, together with the inertia and even foolishness of Mind. Wherefore also the Word says, “Call no man master on earth.”[27] For knowledge is a state of mind that results from demonstration; but Faith is a grace which from what is indemonstrable conducts to what is universal and simple, what is neither with matter, nor matter, nor under matter. But those who believe not, as to be expected, drag all down from heaven, and the region of the invisible, to earth, “absolutely grasping with their hands rocks and oaks,” according to Plato. For, clinging to all such things, they asseverate that that alone exists which can be touched and handled, defining body and essence to be identical: disputing against themselves, they very piously defend the existence of certain intellectual and bodiless forms descending somewhere from above from the invisible world, vehemently maintaining that there is a true essence. “Lo, I make new things,” saith the Word, “which eye hath not seen, nor ear heard, nor hath it entered into the heart of man.”[28] With a new eye, a new ear, a new heart, whatever can be seen and heard is to be apprehended, by the faith and understanding of the disciples of the Lord, who speak, hear, and act spiritually. For there is genuine coin, and other that is spurious; which no less deceives[10] unprofessionals, that it does not the money-changers; who know through having learned how to separate and distinguish what has a false stamp from what is genuine. So the money-changer only says to the unprofessional man that the coin is counterfeit. But the reason why, only the banker’s apprentice, and he that is trained to this department, learns.

Now Aristotle says that the judgment which follows knowledge is in truth faith. Accordingly, faith is something superior to knowledge, and is its criterion. Conjecture, which is only a feeble supposition, counterfeits faith; as the flatterer counterfeits a friend, and the wolf the dog. And as the workman sees that by learning certain things he becomes an artificer, and the helmsman by being instructed in the art will be able to steer; he does not regard the mere wishing to become excellent and good enough, but he must learn it by the exercise of obedience. But to obey the Word, whom we call Instructor, is to believe Him, going against Him in nothing. For how can we take up a position of hostility to God? Knowledge, accordingly, is characterized by faith; and faith, by a kind of divine mutual and reciprocal correspondence, becomes characterized by knowledge.

Epicurus, too, who very greatly preferred pleasure to truth, supposes faith to be a preconception of the mind; and defines preconception to be a grasping at something evident, and at the clear understanding of the thing; and asserts that, without preconception, no one can either inquire, or doubt, or judge, or even argue. How can one, without a preconceived idea of what he is aiming after, learn about that which is the subject of his investigation? He, again, who has learned has already turned his preconception[29] into comprehension. And if he who learns, learns not without a preconceived idea which takes in what is expressed, that man has ears to hear the truth. And happy is the man that speaks to the ears of those who hear; as happy certainly also is he who is a child of obedience. Now to hear is to understand. If, then, faith is nothing else than a preconception of[11] the mind in regard to what is the subject of discourse, and obedience is so called, and understanding and persuasion; no one shall learn aught without faith, since no one [learns aught] without preconception. Consequently there is a more ample demonstration of the complete truth of what was spoken by the prophet, “Unless ye believe, neither will ye understand.” Paraphrasing this oracle, Heraclitus of Ephesus says, “If a man hope not, he will not find that which is not hoped for, seeing it is inscrutable and inaccessible.” Plato the philosopher, also, in The Laws, says, “that he who would be blessed and happy, must be straight from the beginning a partaker of the truth, so as to live true for as long a period as possible; for he is a man of faith. But the unbeliever is one to whom voluntary falsehood is agreeable; and the man to whom involuntary falsehood is agreeable is senseless;[30] neither of which is desirable. For he who is devoid of friendliness, is faithless and ignorant.” And does he not enigmatically say in Euthydemus, that this is “the regal wisdom?” In The Statesman he says expressly, “So that the knowledge of the true king is kingly; and he who possesses it, whether a prince or private person, shall by all means, in consequence of this act, be rightly styled royal.” Now those who have believed in Christ both are and are called Chrestoi (good),[31] as those who are cared for by the true king are kingly. For as the wise are wise by their wisdom, and those observant of law are so by the law; so also those who belong to Christ the King are kings, and those that are Christ’s Christians. Then, in continuation, he adds clearly, “What is right will turn out to be lawful, law being in its nature right reason, and not found in writings or elsewhere.” And the stranger of Elea pronounces the kingly and statesmanlike man “a living law.” Such is he who fulfils the law, “doing the will of the Father,”[32] inscribed on a lofty pillar, and set as an example of divine virtue to all who possess the power of seeing. The[12] Greeks are acquainted with the staves of the Ephori at Lacedæmon, inscribed with the law on wood. But my law, as was said above, is both royal and living; and it is right reason. “Law, which is king of all—of mortals and immortals,” as the Bœotian Pindar sings. For Speusippus,[33] in the first book against Cleophon, seems to write like Plato on this wise: “For if royalty be a good thing, and the wise man the only king and ruler, the law, which is right reason, is good;”[34] which is the case. The Stoics teach what is in conformity with this, assigning kinghood, priesthood, prophecy, legislation, riches, true beauty, noble birth, freedom, to the wise man alone. But that he is exceedingly difficult to find, is confessed even by them.

Accordingly all those above mentioned dogmas appear to have been transmitted from Moses the great to the Greeks. That all things belong to the wise man, is taught in these words: “And because God hath showed me mercy, I have all things.”[35] And that he is beloved of God, God intimates when He says, “The God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, the God of Jacob.”[36] For the first is found to have been expressly called “friend;”[37] and the second is shown to have received a new name, signifying “he that sees God;”[38] while Isaac, God in a figure selected for Himself as a consecrated sacrifice, to be a type to us of the economy of salvation.

Now among the Greeks, Minos the king of nine years’ reign,[13] and familiar friend of Zeus, is celebrated in song; they having heard how once God conversed with Moses, “as one speaking with his friend.”[39] Moses, then, was a sage, king, legislator. But our Saviour surpasses all human nature. He is so lovely, as to be alone loved by us, whose hearts are set on the true beauty, for “He was the true light.”[40] He is shown to be a King, as such hailed by unsophisticated children and by the unbelieving and ignorant Jews, and heralded by the prophets. So rich is He, that He despised the whole earth, and the gold above and beneath it, with all glory, when given to Him by the adversary. What need is there to say that He is the only High Priest, who alone possesses the knowledge of the worship of God?[41] He is Melchizedek, “King of peace,”[42] the most fit of all to head the race of men. A legislator too, inasmuch as He gave the law by the mouth of the prophets, enjoining and teaching most distinctly what things are to be done, and what not. Who of nobler lineage than He whose only Father is God? Come, then, let us produce Plato assenting to those very dogmas. The wise man he calls rich in the Phædrus, when he says, “O dear Pan, and whatever other gods are here, grant me to become fair within; and whatever external things I have, let them be agreeable to what is within. I would reckon the wise man rich.”[43] And the Athenian stranger,[44] finding fault with those who think that those who have many possessions are rich, speaks thus: “For the very rich to be also good is impossible—those, I mean, whom the multitude count rich. Those they call rich, who, among a few men, are owners of the possessions worth most money; which any bad man may possess.” “The whole world of wealth belongs to the believer,”[45] Solomon says, “but not a penny to the unbeliever.” Much more, then, is the scripture to be believed which says, “It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man”[46] to[14] lead a philosophic life. But, on the other hand, it blesses “the poor;”[47] as Plato understood when he said, “It is not the diminishing of one’s resources, but the augmenting of insatiableness, that is to be considered poverty; for it is not slender means that ever constitutes poverty, but insatiableness, from which the good man being free, will also be rich.” And in Alcibiades he calls vice a servile thing, and virtue the attribute of freemen. “Take away from you the heavy yoke, and take up the easy one,”[48] says the Scripture; as also the poets call [vice] a slavish yoke. And the expression, “Ye have sold yourselves to your sins,” agrees with what is said above: “Every one, then, who committeth sin is a slave; and the slave abideth not in the house for ever. But if the Son shall make you free, then shall ye be free, and the truth shall make you free.”[49]

And again, that the wise man is beautiful, the Athenian stranger asserts, in the same way as if one were to affirm that certain persons were just, even should they happen to be ugly in their persons. And in speaking thus with respect to eminent rectitude of character, no one who should assert them to be on this account beautiful would be thought to speak extravagantly. And “His appearance was inferior to all the sons of men,”[50] prophecy predicted.

Plato, moreover, has called the wise man a king, in The Statesman. The remark is quoted above.

These points being demonstrated, let us recur again to our discourse on faith. Well, with the fullest demonstration, Plato proves, that there is need of faith everywhere, celebrating peace at the same time: “For no man will ever be trusty and sound in seditions without entire virtue. There are numbers of mercenaries full of fight, and willing to die in war; but, with a very few exceptions, the most of them are desperadoes and villains, insolent and senseless.” If these observations are right, “every legislator who is even of slight use, will, in making his laws, have an eye to the greatest virtue. Such is fidelity,”[51] which we need at all times, both in[15] peace and in war, and in all the rest of our life, for it appears to embrace the other virtues. “But the best thing is neither war nor sedition, for the necessity of these is to be deprecated. But peace with one another and kindly feeling are what is best.” From these remarks the greatest prayer evidently is to have peace, according to Plato. And faith is the greatest mother of the virtues. Accordingly it is rightly said in Solomon, “Wisdom is in the mouth of the faithful.”[52] Since also Xenocrates, in his book on “Intelligence,” says “that wisdom is the knowledge of first causes and of intellectual essence.” He considers intelligence as twofold, practical and theoretical, which latter is human wisdom. Consequently wisdom is intelligence, but all intelligence is not wisdom. And it has been shown, that the knowledge of the first cause of the universe is of faith, but is not demonstration. For it were strange that the followers of the Samian Pythagoras, rejecting demonstrations of subjects of question, should regard the bare ipse dixit[53] as ground of belief; and that this expression alone sufficed for the confirmation of what they heard, while those devoted to the contemplation of the truth, presuming to disbelieve the trustworthy Teacher, God the only Saviour, should demand of Him tests of His utterances. But He says, “He that hath ears to hear, let him hear.” And who is he? Let Epicharmus say:

Rating some as unbelievers, Heraclitus says, “Not knowing how to hear or to speak;” aided doubtless by Solomon, who says, “If thou lovest to hear, thou shalt comprehend; and if thou incline thine ear, thou shalt be wise.”[55]

[16]

“Lord, who hath believed our report?”[56] Isaiah says. For “faith cometh by hearing, and hearing by the word of God,” saith the apostle. “How then shall they call on Him in whom they have not believed? And how shall they believe on Him whom they have not heard? And how shall they hear without a preacher? And how shall they preach except they be sent? As it is written, How beautiful are the feet of those that publish glad tidings of good things!”[57] You see how he brings faith by hearing, and the preaching of the apostles, up to the word of the Lord, and to the Son of God. We do not yet understand the word of the Lord to be demonstration.

As, then, playing at ball not only depends on one throwing the ball skilfully, but it requires besides one to catch it dexterously, that the game may be gone through according to the rules for ball; so also is it the case that teaching is reliable when faith on the part of those who hear, being, so to speak, a sort of natural art, contributes to the process of learning. So also the earth co-operates, through its productive power, being fit for the sowing of the seed. For there is no good of the very best instruction without the exercise of the receptive faculty on the part of the learner, not even of prophecy, when there is the absence of docility on the part of those who hear. For dry twigs, being ready to receive the power of fire, are kindled with great ease; and the far-famed stone[58] attracts steel through affinity, as the tear of the Succinum drags to itself twigs, and amber sets chaff in motion. And the substances attracted obey them, attracted by a subtle spirit, not as a cause, but as a concurring cause.

There being then a twofold species of vice—that characterized by craft and stealth, and that which leads and drives with violence—the divine Word cries, calling all together; knowing perfectly well those that will not obey; notwithstanding[17] then since to obey or not is in our own power, provided we have not the excuse of ignorance to adduce. He makes a just call, and demands of each according to his strength. For some are able as well as willing, having reached this point through practice and being purified; while others, if they are not yet able, already have the will. Now to will is the act of the soul, but to do is not without the body. Nor are actions estimated by their issue alone; but they are judged also according to the element of free choice in each,—if he chose easily, if he repented of his sins, if he reflected on his failures and repented (μετέγνω), which is (μετὰ ταῦτα ἔγνω) “afterwards knew.” For repentance is a tardy knowledge, and primitive innocence is knowledge. Repentance, then, is an effect of faith. For unless a man believe that to which he was addicted to be sin, he will not abandon it; and if he do not believe punishment to be impending over the transgressor, and salvation to be the portion of him who lives according to the commandments, he will not reform.

Hope, too, is based on faith. Accordingly the followers of Basilides define faith to be, the assent of the soul to any of those things, that do not affect the senses through not being present. And hope is the expectation of the possession of good. Necessarily, then, is expectation founded on faith. Now he is faithful who keeps inviolably what is entrusted to him; and we are entrusted with the utterances respecting God and the divine words, the commands along with the execution of the injunctions. This is the faithful servant, who is praised by the Lord. And when it is said, “God is faithful,” it is intimated that He is worthy to be believed when declaring aught. Now His Word declares; and “God” Himself is “faithful.”[59] How, then, if to believe is to suppose, do the philosophers think that what proceeds from themselves is sure? For the voluntary assent to a preceding demonstration is not supposition, but it is assent to something sure. Who is more powerful than God? Now unbelief is the feeble negative supposition of one opposed to Him; as incredulity is a condition which admits[18] faith with difficulty. Faith is the voluntary supposition and anticipation of pre-comprehension. Expectation is an opinion about the future, and expectation about other things is opinion about uncertainty. Confidence is a strong judgment about a thing. Wherefore we believe Him in whom we have confidence unto divine glory and salvation. And we confide in Him, who is God alone, whom we know, that those things nobly promised to us, and for this end benevolently created and bestowed by Him on us, will not fail.

Benevolence is the wishing of good things to another for his sake. For He needs nothing; and the beneficence and benignity which flow from the Lord terminate in us, being divine benevolence, and benevolence resulting in beneficence. And if to Abraham on his believing it was counted for righteousness; and if we are the seed of Abraham, then we must also believe through hearing. For we are Israelites, who are convinced not by signs, but by hearing. Wherefore it is said, “Rejoice, O barren, that barest not; break forth and cry, thou that didst not travail with child: for more are the children of the desolate than of her who hath an husband.”[60] “Thou hast lived for the fence of the people, thy children were blessed in the tents of their fathers.”[61] And if the same mansions are promised by prophecy to us and to the patriarchs, the God of both the covenants is shown to be one. Accordingly it is added more clearly, “Thou hast inherited the covenant of Israel,”[62] speaking to those called from among the nations, that were once barren, being formerly destitute of this husband, who is the Word,—desolate formerly,—of the bridegroom. Now the just shall live by faith,“[63] which is according to the covenant and the commandments; since these, which are two in name and time, given in accordance with the [divine] economy—being in power one—the old and the new, are dispensed through the Son by one God. As the apostle also says in the Epistle to the Romans, “For therein is the righteousness of God revealed from faith to faith,” teaching the one salvation which from prophecy to the Gospel is perfected by one and the same Lord. “This[19] charge,” he says, “I commit to thee, son Timothy, according to the prophecies which went before on thee, that thou by them mightest war the good warfare; holding faith, and a good conscience; which some having put away, concerning faith have made shipwreck,”[64] because they defiled by unbelief the conscience that comes from God. Accordingly, faith may not, any more, with reason, be disparaged in an offhand way, as simple and vulgar, appertaining to anybody. For, if it were a mere human habit, as the Greeks supposed, it would have been extinguished. But if it grow, and there be no place where it is not; then I affirm, that faith, whether founded in love, or in fear, as its disparagers assert, is something divine; which is neither rent asunder by other mundane friendship, nor dissolved by the presence of fear. For love, on account of its friendly alliance with faith, makes men believers; and faith, which is the foundation of love, in its turn introduces the doing of good; since also fear, the pædagogue of the law, is believed to be fear by those, by whom it is believed. For, if its existence is shown in its working, it is yet believed when about to do and threatening, and when not working and present; and being believed to exist, it does not itself generate faith, but is by faith tested and proved trustworthy. Such a change, then, from unbelief to faith—and to trust in hope and fear, is divine. And, in truth, faith is discovered, by us, to be the first movement towards salvation; after which fear, and hope, and repentance, advancing in company with temperance and patience, lead us to love and knowledge. Rightly, therefore, the Apostle Barnabas says, “From the portion I have received I have done my diligence to send by little and little to you; that along with your faith you may also have perfect knowledge. Fear and patience are then helpers of your faith; and our allies are long-suffering and temperance. These, then,” he says, “in what respects the Lord, continuing in purity, there rejoice along with them, wisdom, understanding, intelligence, knowledge.” The forementioned virtues being, then, the elements of knowledge; the result is that faith is more elementary, being as necessary[20] to the Gnostic,[65] as respiration to him that lives in this world is to life. And as without the four elements it is not possible to live, so neither can knowledge be attained without faith. It is then the support of truth.

Those, who denounce fear, assail the law; and if the law, plainly also God, who gave the law. For these three elements are of necessity presented in the subject on hand: the ruler, his administration, and the ruled. If, then, according to hypothesis, they abolish the law; then, by necessary consequence, each one who is led by lust, courting pleasure, must neglect what is right and despise the Deity, and fearlessly indulge in impiety and injustice together, having dashed away from the truth.

Yea, say they, fear is an irrational aberration,[66] and perturbation of mind. What sayest thou? And how can this definition be any longer maintained, seeing the commandment is given me by the Word? But the commandment forbids, hanging fear over the head of those who have incurred[67] admonition for their discipline.

Fear is not then irrational. It is therefore rational. How could it be otherwise, exhorting as it does, Thou shalt not kill, Thou shalt not commit adultery, Thou shalt not steal, Thou shalt not bear false witness? But if they will quibble about the names, let the philosophers term the fear of the law, cautious fear, (εὐλάβεια,) which is a shunning (ἔκκλισις) agreeable to reason. Such Critolaus of Phasela not inaptly called fighters about names (ὀνοματομάχοι). The commandment, then, has already appeared fair and lovely even in the highest degree, when conceived under a change of name.[21] Cautious fear (εὐλάβεια) is therefore shown to be reasonable, being the shunning of what hurts; from which arises repentance for previous sins. “For the fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom; good understanding is to all that do it.”[68] He calls wisdom a doing, which is the fear of the Lord paving the way for wisdom. But if the law produces fear, the knowledge of the law is the beginning of wisdom; and a man is not wise without law. Therefore those who reject the law are unwise; and in consequence they are reckoned godless (ἄθεοι). Now instruction is the beginning of wisdom. “But the ungodly despise wisdom and instruction,”[69] saith the Scripture.

Let us see what terrors the law announces. If it is the things which hold an intermediate place between virtue and vice, such as poverty, disease, obscurity, and humble birth, and the like, these things civil laws hold forth, and are praised for so doing. And those of the Peripatetic school, who introduce three kinds of good things, and think that their opposites are evil, this opinion suits. But the law given to us enjoins us to shun what are in reality bad things—adultery, uncleanness, pæderasty, ignorance, wickedness, soul-disease, death (not that which severs the soul from the body, but that which severs the soul from truth). For these are vices in reality, and the workings that proceed from them are dreadful and terrible. “For not unjustly,” say the divine oracles, “are the nets spread for birds; for they who are accomplices in blood treasure up evils to themselves.”[70] How, then, is the law still said to be not good by certain heresies that clamorously appeal to the apostle, who says, “For by the law is the knowledge of sin?”[71] To whom we say, The law did not cause, but showed sin. For, enjoining what is to be done, it reprehended what ought not to be done. And it is the part of the good to teach what is salutary, and to point out what is deleterious; and to counsel the practice[22] of the one, and to command to shun the other. Now the apostle, whom they do not comprehend, said that by the law the knowledge of sin was manifested, not that from it it derived its existence. And how can the law be not good, which trains, which is given as the instructor (παιδαγωγός) to Christ,[72] that being corrected by fear, in the way of discipline, in order to the attainment of the perfection which is by Christ? “I will not,” it is said, “the death of the sinner, as his repentance.”[73] Now the commandment works repentance; inasmuch as it deters[74] from what ought not to be done, and enjoins good deeds. By ignorance he means, in my opinion, death. “And he that is near the Lord is full of stripes.”[75] Plainly, he, that draws near to knowledge, has the benefit of perils, fears, troubles, afflictions, by reason of his desire for the truth. “For the son who is instructed turns out wise, and an intelligent son is saved from burning. And an intelligent son will receive the commandments.”[76] And Barnabas the apostle having said, “Woe to those who are wise in their own conceits, clever in their own eyes,”[77] added, “Let us become spiritual, a perfect temple to God; let us, as far as in us lies, practise the fear of God, and strive to keep His commands, that we may rejoice in His judgments.” Whence “the fear of God” is divinely said to be the beginning of wisdom.[78]

Here the followers of Basilides, interpreting this expression, say, “that the Prince,[79] having heard the speech of[23] the Spirit, who was being ministered to, was struck with amazement both with the voice and the vision, having had glad tidings beyond his hopes announced to him; and that his amazement was called fear, which became the origin of wisdom, which distinguishes classes, and discriminates, and perfects, and restores. For not the world alone, but also the election, He that is over all has set apart and sent forth.”

And Valentinus appears also in an epistle to have adopted such views. For he writes in these very words: “And as[80] terror fell on the angels at this creature, because he uttered things greater than proceeded from his formation, by reason of the being in him who had invisibly communicated a germ of the supernal essence, and who spoke with free utterance; so also among the tribes of men in the world, the works of men became terrors to those who made them,—as, for example, images and statues. And the hands of all fashion things to bear the name of God: for Adam formed into the name of man inspired the dread attaching to the pre-existent man, as having his being in him; and they were terror-stricken, and speedily marred the work.”

But there being but one First Cause, as will be shown afterwards, these men will be shown to be inventors of chatterings and chirpings. But since God deemed it advantageous, that from the law and the prophets, men should receive a preparatory discipline by the Lord, the fear of the Lord was called the beginning of wisdom, being given by the Lord, through Moses, to the disobedient and hard of heart. For those whom reason convinces not, fear tames; which also the Instructing Word, foreseeing from the first, and purifying by each of these methods, adapted the instrument suitably for piety. Consternation is, then, fear at a strange apparition, or at an unlooked-for representation—such as, for example, a message; while fear is an excessive wonderment on account of something which arises or is. They do not then perceive that they represent by means of amazement the God who is highest and is extolled by them, as subject to perturbation and antecedent[24] to amazement as having been in ignorance. If indeed ignorance preceded amazement; and if this amazement and fear, which is the beginning of wisdom, is the fear of God, then in all likelihood ignorance as cause preceded both the wisdom of God and all creative work, and not only these, but restoration and even election itself. Whether, then, was it ignorance of what was good or what was evil?

Well, if of good, why does it cease through amazement? And minister and preaching and baptism are [in that case] superfluous to them. And if of evil, how can what is bad be the cause of what is best? For had not ignorance preceded, the minister would not have come down, nor would have amazement seized on “the Prince,” as they say; nor would he have attained to a beginning of wisdom from fear, in order to discrimination between the elect and those that are mundane. And if the fear of the pre-existent man made the angels conspire against their own handiwork, under the idea that an invisible germ of the supernal essence was lodged within that creation, or through unfounded suspicion excited envy, which is incredible, the angels became murderers of the creature which had been entrusted to them, as a child might be, they being thus convicted of the grossest ignorance. Or suppose they were influenced by being involved in foreknowledge. But they would not have conspired against what they foreknew in the assault they made; nor would they have been terror-struck at their own work, in consequence of foreknowledge, on their perceiving the supernal germ. Or, finally, suppose, trusting to their knowledge, they dared (but this also were impossible for them), on learning the excellence that is in the Pleroma, to conspire against man. Furthermore also they laid hands on that which was according to the image, in which also is the archetype, and which, along with the knowledge that remains, is indestructible.

To these, then, and certain others, especially the Marcionites, the Scripture cries, though they listen not, “He that heareth me shall rest with confidence in peace, and shall be tranquil, fearless of all evil.”[81]

[25]

What, then, will they have the law to be? They will not call it evil, but just; distinguishing what is good from what is just. But the Lord, when He enjoins us to dread evil, does not exchange one evil for another, but abolishes what is opposite by its opposite. Now evil is the opposite of good, as what is just is of what is unjust. If, then, that absence of fear, which the fear of the Lord produces, is called the beginning of what is good,[82] fear is a good thing. And the fear which proceeds from the law is not only just, but good, as it takes away evil. But introducing absence of fear by means of fear, it does not produce apathy by means of mental perturbation, but moderation of feeling by discipline. When, then, we hear, “Honour the Lord, and be strong: but fear not another besides Him,”[83] we understand it to be meant fearing to sin, and following the commandments given by God, which is the honour that cometh from God. For the fear of God is Δέος [in Greek]. But if fear is perturbation of mind, as some will have it that fear is perturbation of mind, yet all fear is not perturbation. Superstition is indeed perturbation of mind; being the fear of demons, that produce and are subject to the excitement of passion. On the other hand, consequently, the fear of God, who is not subject to perturbation, is free of perturbation. For it is not God, but falling away from God, that the man is terrified for. And he who fears this—that is, falling into evils—fears and dreads those evils. And he who fears a fall, wishes himself to be free of corruption and perturbation. “The wise man, fearing, avoids evil: but the foolish, trusting, mixes himself with it,” says the Scripture; and again it says, “In the fear of the Lord is the hope of strength.”[84]

[26]

Such a fear, accordingly, leads to repentance and hope. Now hope is the expectation of good things, or an expectation sanguine of absent good; and favourable circumstances are assumed in order to good hope, which we have learned leads on to love. Now love turns out to be consent in what pertains to reason, life, and manners, or in brief, fellowship in life, or it is the intensity of friendship and of affection, with right reason, in the enjoyment of associates. And an associate (ἑταῖρος) is another self;[85] just as we call those, brethren, who are regenerated by the same word. And akin to love is hospitality, being a congenial art devoted to the treatment of strangers. And those are strangers, to whom the things of the world are strange. For we regard as worldly those, who hope in the earth and carnal lusts. “Be not conformed,” says the apostle, “to this world: but be ye transformed in the renewal of the mind, that ye may prove what is that good, and acceptable, and perfect will of God.”[86] from ἕτερος.]

Hospitality, therefore, is occupied in what is useful for strangers; and guests (ἐπίξενοι) are strangers (ξένοι); and friends are guests; and brethren are friends. “Dear brother,”[87] says Homer.

Philanthropy, in order to which also, is natural affection, being a loving treatment of men, and natural affection, which is a congenial habit exercised in the love of friends or domestics, follow in the train of love. And if the real man within us is the spiritual, philanthropy is brotherly love to those who participate, in the same spirit. Natural affection, on the other hand, is the preservation of good-will, or of affection; and affection is its perfect demonstration;[88] and to be beloved is to please in behaviour, by drawing and attracting. And persons are brought to sameness by consent, which is the[27] knowledge of the good things that are enjoyed in common. For community of sentiment (ὁμογνωμοσύνη) is harmony of opinions (συμφωνία γνωμῶν). “Let your love be without dissimulation,” it is said; “and abhorring what is evil, let us become attached to what is good, to brotherly love,” and so on, down to “If it be possible, as much as lieth in you, living peaceably with all men.” Then “be not overcome of evil,” it is said, “but overcome evil with good.”[89] And the same apostle owns that he bears witness to the Jews, “that they have a zeal of God, but not according to knowledge. For, being ignorant of God’s righteousness, and seeking to establish their own, they have not submitted themselves to the righteousness of God.”[90] For they did not know and do the will of the law; but what they supposed, that they thought the law wished. And they did not believe the law as prophesying, but the bare word; and they followed through fear, not through disposition and faith. “For Christ is the end of the law for righteousness,”[91] who was prophesied by the law to every one that believeth. Whence it was said to them by Moses, “I will provoke you to jealousy by them that are not a people; and I will anger you by a foolish nation, that is, by one that has become disposed to obedience.”[92] And by Isaiah it is said, “I was found of them that sought me not; I was made manifest to them that inquired not after me,”[93]—manifestly previous to the coming of the Lord; after which to Israel, the things prophesied, are now appropriately spoken: “I have stretched out my hands all the day long to a disobedient and gainsaying people.” Do you see the cause of the calling from among the nations, clearly declared, by the prophet, to be the disobedience and gainsaying of the people? Then the goodness of God is shown also in their case. For the apostle says, “But through their transgression salvation is come to the Gentiles, to provoke them to jealousy,”[94] and to willingness to repent. And the Shepherd, speaking plainly of those[28] who had fallen asleep, recognises certain righteous among Gentiles and Jews, not only before the appearance of Christ, but before the law, in virtue of acceptance before God,—as Abel, as Noah, as any other righteous man. He says accordingly, “that the apostles and teachers, who had preached the name of the Son of God, and had fallen asleep, in power and by faith, preached to those that had fallen asleep before.” Then he subjoins: “And they gave them the seal of preaching. They descended, therefore, with them into the water, and again ascended. But these descended alive, and again ascended alive. But those, who had fallen asleep before, descended dead, but ascended alive. By these, therefore, they were made alive, and knew the name of the Son of God. Wherefore also they ascended with them, and fitted into the structure of the tower, and unhewn were built up together: they fell asleep in righteousness and in great purity, but wanted only this seal.”[95] “For when the Gentiles, which have not the law, do by nature the things of the law, these having not the law, are a law unto themselves,”[96] according to the apostle.

As, then, the virtues follow one another, why need I say what has been demonstrated already, that faith hopes through repentance, and fear through faith; and patience and practice in these along with learning terminate in love, which is perfected by knowledge? But that is necessarily to be noticed, that the Divine alone is to be regarded as naturally wise. Therefore also wisdom, which has taught the truth, is the power of God; and in it the perfection of knowledge is embraced. The philosopher loves and likes the truth, being now considered as a friend, on account of his love, from his being a true servant. The beginning of knowledge is wondering at objects, as Plato says in his Theætetus; and Matthew exhorting in the Traditions, says, “Wonder at what is before you;” laying this down first as the foundation of further knowledge. So also in the Gospel to the Hebrews it is written, “He that wonders shall reign, and he that has reigned shall rest.” It is impossible, therefore, for an ignorant[29] man, while he remains ignorant, to philosophize, not having apprehended the idea of wisdom; since philosophy is an effort to grasp that which truly is, and the studies that conduce thereto. And it is not the rendering of one[97] accomplished in good habits of conduct, but the knowing how we are to use and act and labour, according as one is assimilated to God. I mean God the Saviour, by serving the God of the universe through the High Priest, the Word, by whom what is in truth good and right is beheld. Piety is conduct suitable and corresponding to God.

These three things, therefore, our philosopher attaches himself to: first, speculation; second, the performance of the precepts; third, the forming of good men;—which, concurring, form the Gnostic. Whichever of these is wanting, the elements of knowledge limp. Whence the Scripture divinely says, “And the Lord spake to Moses, saying, Speak to the children of Israel, and thou shalt say to them, I am the Lord your God. According to the customs of the land of Egypt, in which ye have dwelt, ye shall not do; and according to the customs of Canaan, into which I bring you, ye shall not do; and in their usages ye shall not walk. Ye shall perform my judgments, and keep my precepts, and walk in them: I am the Lord your God. And ye shall keep all my commandments, and do them. He that doeth them shall live in them. I am the Lord your God.”[98] Whether, then, Egypt and the land of Canaan be the symbol of the world and of deceit, or of sufferings and afflictions; the oracle shows us what must be abstained from, and what, being divine and not worldly, must be observed. And when it is said, “The man that doeth them shall live in them,”[99] it declares both the correction[30] of the Hebrews themselves, and the training and advancement of us who are nigh:[100] it declares at once their life and ours. For “those who were dead in sins are quickened together with Christ,”[101] by our covenant. For Scripture, by the frequent reiteration of the expression, “I am the Lord your God,” shames in such a way as most powerfully to dissuade, by teaching us to follow God who gave the commandments, and gently admonishes us to seek God and endeavour to know Him as far as possible; which is the highest speculation, that which scans the greatest mysteries, the real knowledge, that which becomes irrefragable by reason. This alone is the knowledge of wisdom, from which rectitude of conduct is never disjoined.

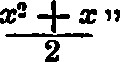

But the knowledge of those who think themselves wise, whether the barbarian sects or the philosophers among the Greeks, according to the apostle, “puffeth up.”[102] But that knowledge, which is the scientific demonstration of what is delivered according to the true philosophy, is founded on faith. Now, we may say that it is that process of reason which, from what is admitted, procures faith in what is disputed. Now, faith being twofold—the faith of knowledge and that of opinion—nothing prevents us from calling demonstration twofold, the one resting on knowledge, the other on opinion; since also knowledge and foreknowledge are designated as twofold, that which is essentially accurate, that which is defective. And is not the demonstration, which we possess, that alone which is true, as being supplied out of the divine Scriptures, the sacred writings, and out of the “God-taught wisdom,” according to the apostle? Learning, then, is also obedience[31] to the commandments, which is faith in God. And faith is a power of God, being the strength of the truth. For example, it is said, “If ye have faith as a grain of mustard, ye shall remove the mountain.”[103] And again, “According to thy faith let it be to thee.”[104] And one is cured, receiving healing by faith; and the dead is raised up in consequence of the power of one believing that he would be raised. The demonstration, however, which rests on opinion is human, and is the result of rhetorical arguments or dialectic syllogisms. For the highest demonstration, to which we have alluded, produces intelligent faith by the adducing and opening up of the Scriptures to the souls of those who desire to learn; the result of which is knowledge (gnosis). For if what is adduced in order to prove the point at issue is assumed to be true, as being divine and prophetic, manifestly the conclusion arrived at by inference from it will consequently be inferred truly; and the legitimate result of the demonstration will be knowledge. When, then, the memorial of the celestial and divine food was commanded to be consecrated in the golden pot, it was said, “The omer was the tenth of the three measures.”[105] For in ourselves, by the three measures are indicated three criteria; sensation of objects of sense, speech,—of spoken names and words, and the mind,—of intellectual objects. The Gnostic, therefore, will abstain from errors in speech, and thought, and sensation, and action, having heard “that he that looks so as to lust hath committed adultery;”[106] and reflecting that “blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God;”[107] and knowing this, “that not what enters into the mouth defileth, but that it is what cometh forth by the mouth that defileth the man. For out of the heart proceed thoughts.”[108] This, as I think, is the true and just measure according to God, by which things capable of measurement are measured, the decad which is comprehensive of man; which summarily the three above-mentioned measures pointed out. There are[32] body and soul, the five senses, speech, the power of reproduction—the intellectual or the spiritual faculty, or whatever you choose to call it. And we must, in a word, ascending above all the others, stop at the mind; as also certainly in the universe overleaping the nine divisions, the first consisting of the four elements put in one place for equal interchange; and then the seven wandering stars and the one that wanders not, the ninth, to the perfect number, which is above the nine,[109] and the tenth division, we must reach to the knowledge of God, to speak briefly, desiring the Maker after the creation. Wherefore the tithes both of the ephah and of the sacrifices were presented to God; and the paschal feast began with the tenth day, being the transition from all trouble, and from all objects of sense.

The Gnostic is therefore fixed by faith; but the man who thinks himself wise touches not what pertains to the truth, moved as he is by unstable and wavering impulses. It is therefore reasonably written, “Cain went forth from the face of God, and dwelt in the land of Naid, over against Eden.” Now Naid is interpreted commotion, and Eden delight; and Faith, and Knowledge, and Peace are delight, from which he that has disobeyed is cast out. But he that is wise in his own eyes will not so much as listen to the beginning of the divine commandments; but, as if his own teacher, throwing off the reins, plunges voluntarily into a billowy commotion, sinking down to mortal and created things from the uncreated knowledge, holding various opinions at various times. “Those who have no guidance fall like leaves.”[110]

Reason, the governing principle, remaining unmoved and guiding the soul, is called its pilot. For access to the Immutable is obtained by a truly immutable means. Thus Abraham was stationed before the Lord, and approaching spoke.[111] And to Moses it is said, “But do thou stand there[33] with me.”[112] And the followers of Simon wish to be assimilated in manners to the standing form which they adore. Faith, therefore, and the knowledge of the truth, render the soul, which makes them its choice, always uniform and equable. For congenial to the man of falsehood is shifting, and change, and turning away, as to the Gnostic are calmness, and rest, and peace. As, then, philosophy has been brought into evil repute by pride and self-conceit, so also gnosis by false gnosis called by the same name; of which the apostle writing says, “O Timothy, keep that which is committed to thy trust, avoiding the profane and vain babblings and oppositions of science (gnosis) falsely so called; which some professing, have erred concerning the faith.”[113]

Convicted by this utterance, the heretics reject the Epistles to Timothy. Well, then, if the Lord is the truth, and wisdom, and power of God, as in truth He is, it is shown that the real Gnostic is he that knows Him, and His Father by Him. For his sentiments are the same with him who said, “The lips of the righteous know high things.”[114]

Faith as also Time being double, we shall find virtues in pairs both dwelling together. For memory is related to past time, hope to future. We believe that what is past did, and that what is future will take place. And, on the other hand, we love, persuaded by faith that the past was as it was, and by hope expecting the future. For in everything love attends the Gnostic, who knows one God. “And, behold, all things which He created were very good.”[115] He both knows and admires. Godliness adds length of life; and the fear of the Lord adds days. As, then, the days are a portion of life in its progress, so also fear is the beginning of love, becoming by development[34] faith, then love. But it is not as I fear and hate a wild beast (since fear is twofold) that I fear the father, whom I fear and love at once. Again, fearing lest I be punished, I love myself in assuming fear. He who fears to offend his father, loves himself. Blessed then is he who is found possessed of faith, being, as he is, composed of love and fear. And faith is power in order to salvation, and strength to eternal life. Again, prophecy is foreknowledge; and knowledge the understanding of prophecy; being the knowledge of those things known before by the Lord who reveals all things.

The knowledge, then, of those things which have been predicted shows a threefold result,—either one that has happened long ago, or exists now, or about to be. Then the extremes[116] either of what is accomplished or of what is hoped for fall under faith; and the present action furnishes persuasive arguments for the confirmation of both the extremes. For if, prophecy being one, one part is accomplishing and another is fulfilled; hence the truth, both what is hoped for and what is past is confirmed. For it was first present; then it became past to us; so that the belief of what is past is the apprehension of a past event, and the hope which is future the apprehension of a future event.

And not only the Platonists, but the Stoics, say that assent is in our own power. All opinion then, and judgment, and supposition, and knowledge, by which we live and have perpetual intercourse with the human race, is an assent; which is nothing else than faith. And unbelief being defection from faith, shows both assent and faith to be possessed of power; for non-existence cannot be called privation. And if you consider the truth, you will find man naturally misled so as to give assent to what is false, though possessing the resources necessary for belief in the truth. “The virtue, then, that encloses the church in its grasp,” as the Shepherd says,[117] “is Faith, by which the elect of God are saved; and that which acts the man is Self-restraint. And these are followed by Simplicity, Knowledge, Innocence, Decorum, Love,” and all[35] these are the daughters of Faith. And again, “Faith leads the way, fear upbuilds, and love perfects.” Accordingly he[118] says, the Lord is to be feared in order to edification, but not the devil to destruction. And again, the works of the Lord—that is, His commandments—are to be loved and done; but the works of the devil are to be dreaded and not done. For the fear of God trains and restores to love; but the fear of the works of the devil has hatred dwelling along with it. The same also says “that repentance is high intelligence. For he that repents of what he did, no longer does or says as he did. But by torturing himself for his sins, he benefits his soul. Forgiveness of sins is therefore different from repentance; but both show what is in our power.”

He, then, who has received the forgiveness of sins ought to sin no more. For, in addition to the first and only repentance from sins (this is from the previous sins in the first and heathen life—I mean that in ignorance), there is forthwith proposed to those who have been called, the repentance which cleanses the seat of the soul from transgressions, that faith may be established. And the Lord, knowing the heart, and foreknowing the future, foresaw both the fickleness of man and the craft and subtlety of the devil from the first, from the beginning; how that, envying man for the forgiveness of sins, he would present to the servants of God certain causes of sins; skilfully working mischief, that they might fall together with himself. Accordingly, being very merciful, He has vouchsafed, in the case of those who, though in faith, fall into any transgression, a second repentance; so that should any one be tempted after his calling, overcome by force and fraud, he may receive still a repentance not to be repented of. “For if we sin wilfully after that we have received the knowledge[36] of the truth, there remaineth no more a sacrifice for sins, but a certain fearful looking for of judgment and fiery indignation, which shall devour the adversaries.”[119] But continual and successive repentings for sins differ nothing from the case of those who have not believed at all, except only in their consciousness that they do sin. And I know not which of the two is worst, whether the case of a man who sins knowingly, or of one who, after having repented of his sins, transgresses again. For in the process of proof sin appears on each side,—the sin which in its commission is condemned by the worker of the iniquity, and that of the man who, foreseeing what is about to be done, yet puts his hand to it as a wickedness. And he who perchance gratifies himself in anger and pleasure, gratifies himself in he knows what; and he who, repenting of that in which he gratified himself, by rushing again into pleasure, is near neighbour to him who has sinned wilfully at first. For one, who does again that of which he has repented, and condemning what he does, performs it willingly.