VOLUMES III. IV.

BOSTON:

PUBLISHED BY BRADBURY, SODEN & CO.

10, SCHOOL STREET, AND 127, NASSAU STREET, NEW YORK.

1843.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1842, by S. G. Goodrich, in

the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of Massachusetts.

EDITED BY

S. G. GOODRICH,

AUTHOR OF PETER PARLEY’S TALES.

VOLUME III.

BOSTON:

BRADBURY, SODEN, & CO.,

No. 10 School Street, and 127 Nassau Street, New York.

1842.

JANUARY TO JUNE, 1842.

| The New Year, | 1 |

| Wonders of Geology, | 3 |

| The Siberian Sable-Hunter, | 7, 65, 122 |

| Merry’s Adventures, | 12, 36, 79, 150, 177 |

| Repentance, | 16 |

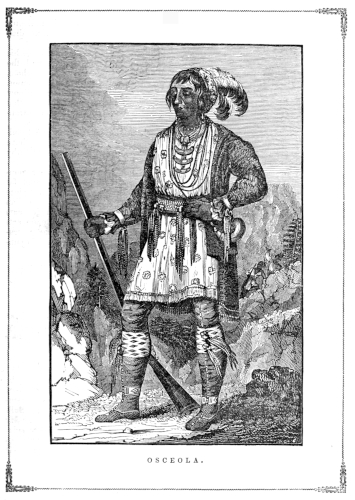

| Indians of America, | 17, 41, 74, 97, 131, 165 |

| Story of Philip Brusque, | 21, 60, 87 |

| Solon, the Grecian Lawgiver, | 25 |

| How to settle a Dispute without Pistols, | 26 |

| The Painter and his Master, | 27 |

| The Turkey and Rattlesnake,—a Fable, | 28 |

| Flowers, | 28 |

| Christmas, | 29 |

| Puzzles, | 31, 95, 126, 159, 190 |

| Varieties, | 31, 188 |

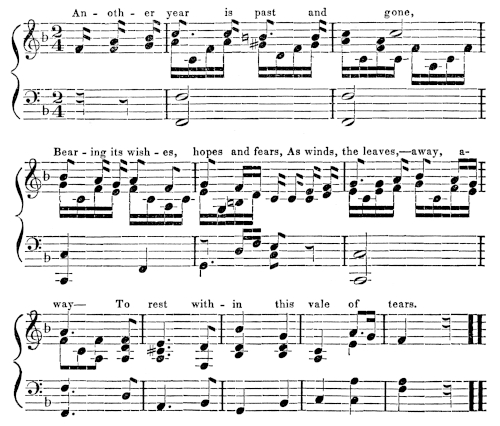

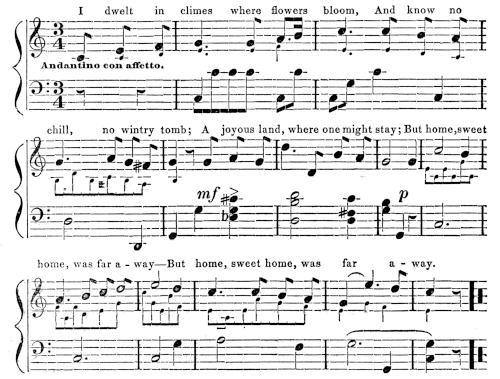

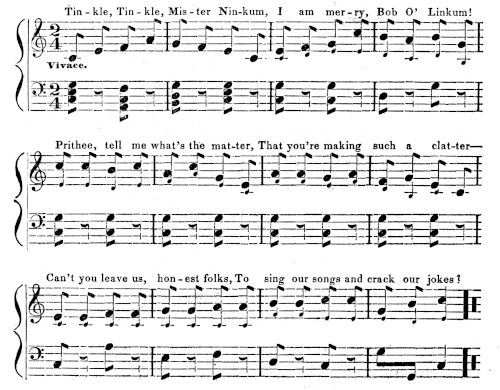

| Hymn for the New Year,—Music, | 32 |

| Anecdote of a Traveller, | 33 |

| Dr. Cotton and the Sheep, | 34 |

| The Robin, | 34 |

| Echo,—A Dialogue, | 35 |

| The Lion and the Ass, | 35 |

| National Characteristics, | 35 |

| The Two Seekers, | 38 |

| Resistance to Pain, | 40 |

| The Voyages, Travels and Experiences of Thomas Trotter, | 45, 84, 102, 139, 182 |

| Cheerful Cherry, | 48 |

| The War in Florida, | 56 |

| Composition, | 58 |

| Natural Curiosities of New Holland, | 59 |

| Beds, | 61 |

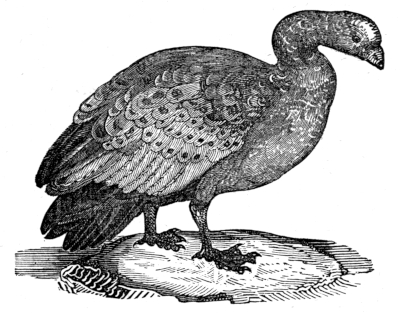

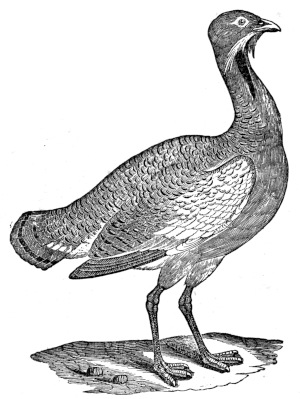

| The Great Bustard, | 62 |

| The Tartar, | 63 |

| Answers to Puzzles, | 63 |

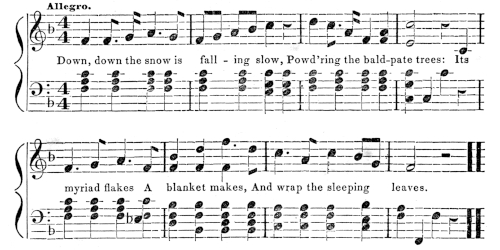

| The Snow-Storm,—Music, | 64 |

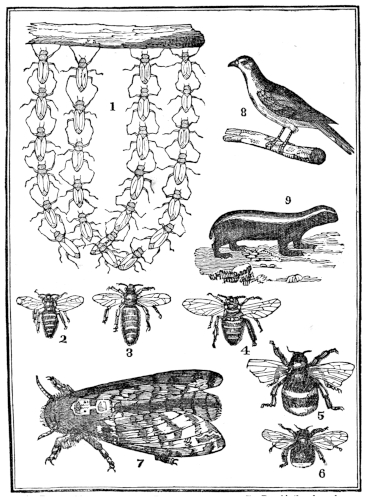

| Bees, | 69 |

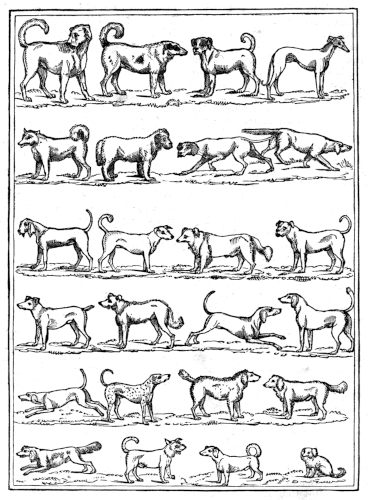

| The several varieties of Dogs, | 72 |

| Anecdote of the Indians, | 73 |

| The Wisdom of God, | 77 |

| The Canary Bird, | 78 |

| The Paper Nautilus, | 79 |

| The Zodiac, | 83 |

| The Tanrec, | 89 |

| Letter from a Correspondent, | 89 |

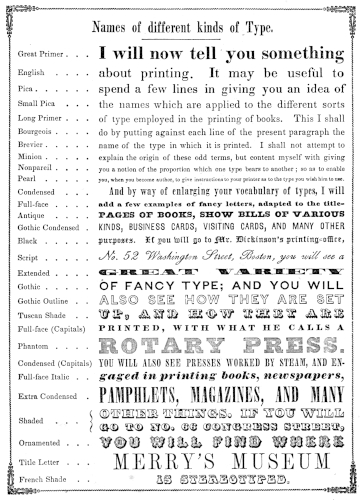

| Different kinds of Type, | 91 |

| The Three Sisters, | 92 |

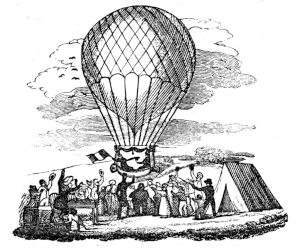

| The Zephyr, | 95 |

| To Correspondents, | 95, 127, 158, 189 |

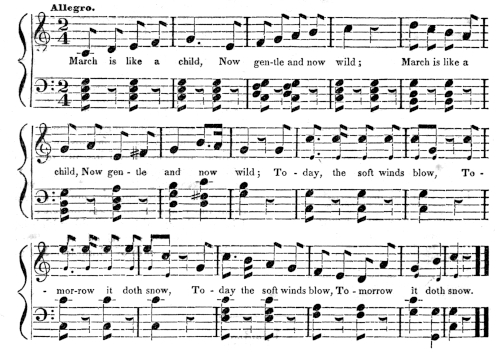

| March,—A Song, | 96 |

| Butterflies, | 101 |

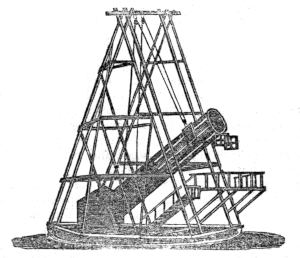

| Herschel the Astronomer, | 107 |

| Truth and Falsehood,—An Allegory, | 108 |

| The Chimpansé, | 110 |

| The Sugar-Cane, | 111 |

| Dialogue on Politeness, | 112 |

| The Date Tree, | 114 |

| Dress, | 115 |

| Eagles, and other matters, | 117 |

| April, | 120 |

| The Prophet Jeremiah, | 121 |

| Letter from a Subscriber, | 124 |

| Toad-Stools and Mushrooms, | 125 |

| Return of Spring, | 126 |

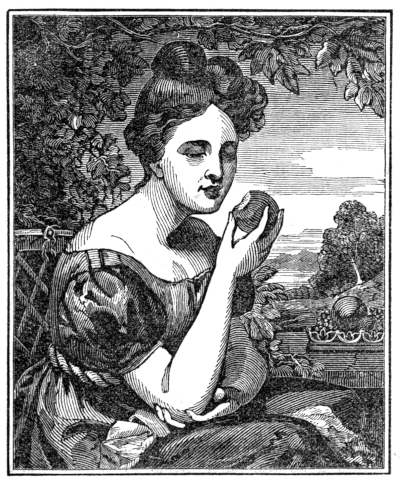

| Smelling, | 129 |

| Isaac and Rebekah, | 135 |

| Mr. Catlin and his Horse Charley, | 136 |

| The Kitchen, | 138 |

| Knights Templars, | 145 |

| The Garden of Peace, | 146 |

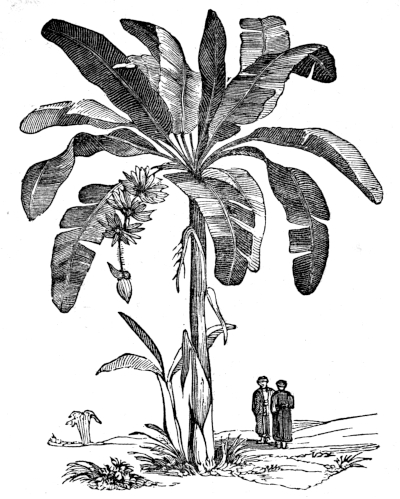

| The Banana, | 148 |

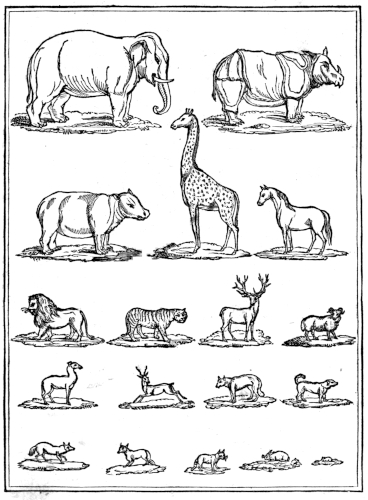

| Comparative Size of Animals, | 149 |

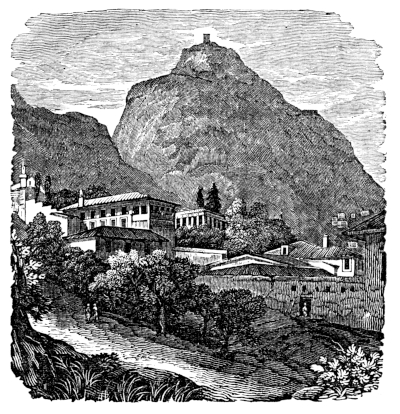

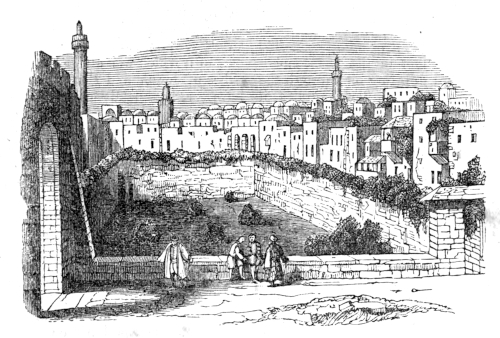

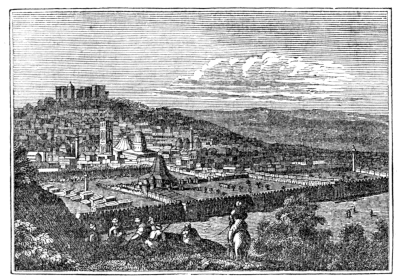

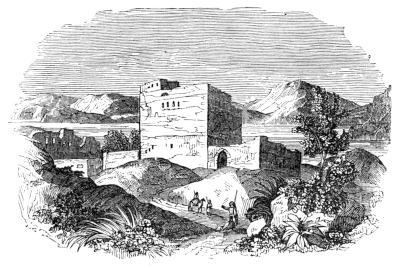

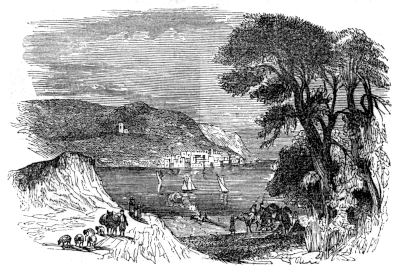

| Misitra and the Ancient Sparta, | 155 |

| Absence of Mind, | 155 |

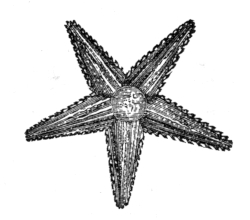

| The Star Fish, | 156 |

| Where is thy Home? | 157 |

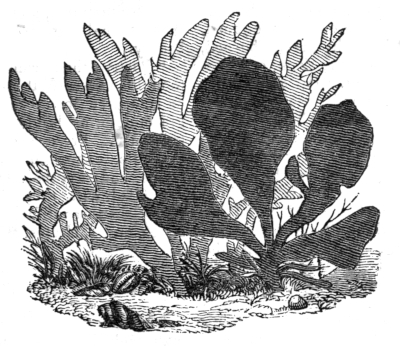

| Sea-Weed, | 157 |

| Inquisitive Jack and his Aunt Piper, | 158 |

| “Far Away,”—the Bluebird’s Song, | 160 |

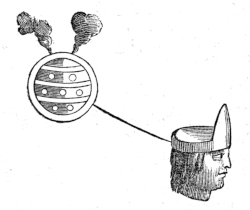

| The Sense of Hearing, | 161 |

| “Fresh Flowers,” | 162 |

| June, | 164 |

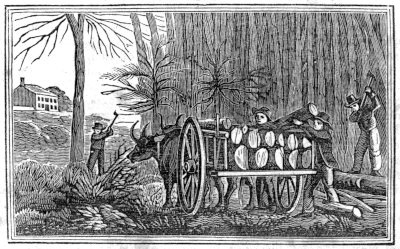

| House-Building, | 173 |

| Edwin the Rabbit-fancier, | 175 |

| Who planted the Oaks? | 181 |

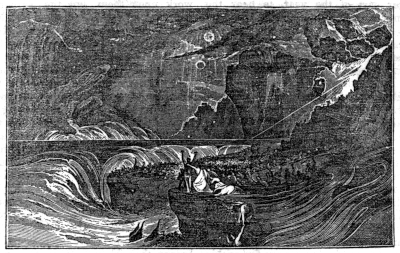

| The Deluge, | 186 |

| Page for Little Readers, | 187 |

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1842, by S. G. Goodrich, in the Clerk’s Office of the

District Court of Massachusetts.

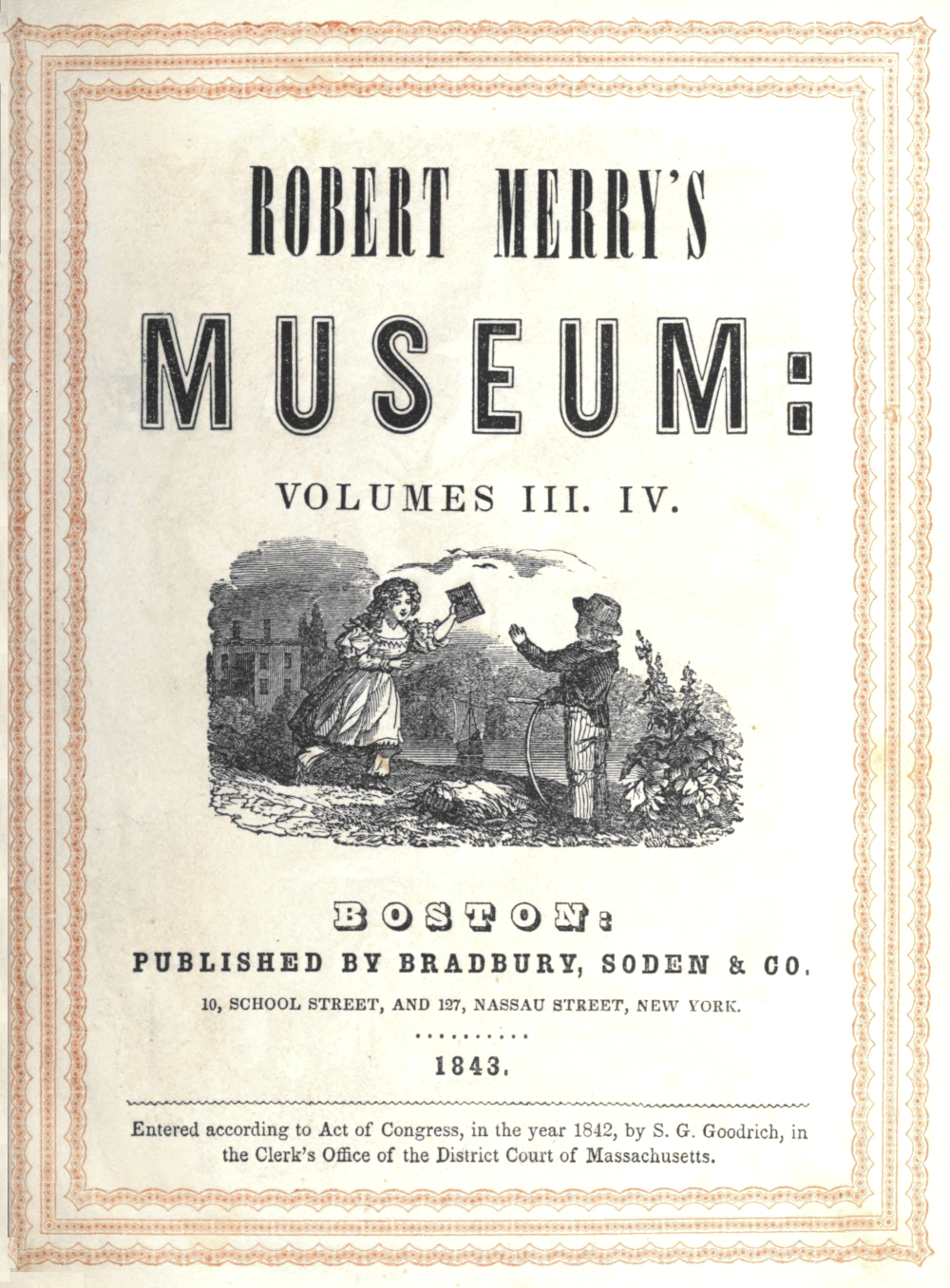

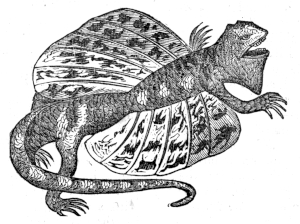

THE IGUANADON.

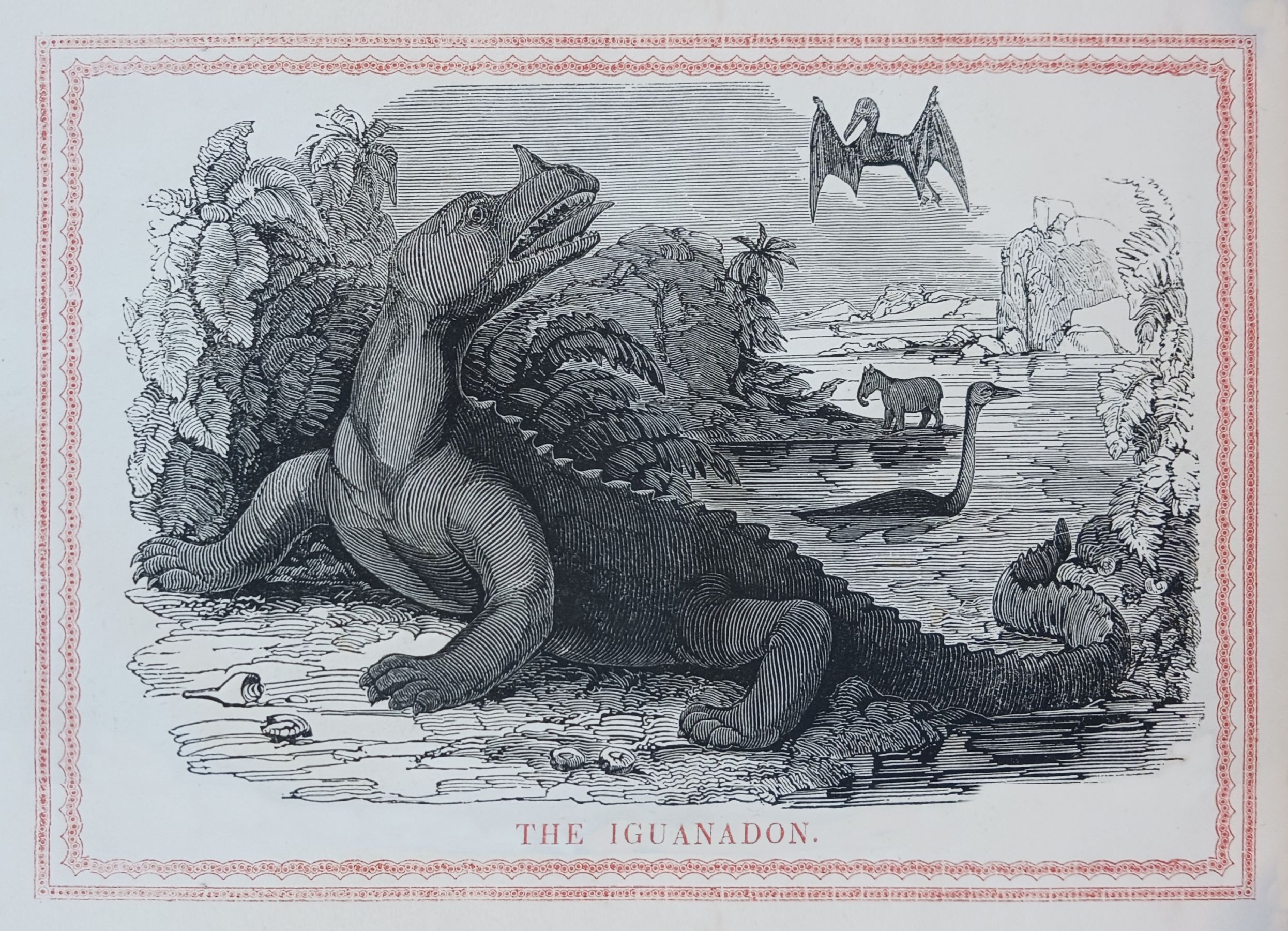

Tom Stedfast.

There are few days in all the year that are pleasanter than the first of January—New Year’s Day. It is a day when we all salute each other with a cheerful greeting;—when children say to their parents, as they meet in the [Pg 2] morning, “I wish you a happy new year!” and the parents reply, “A happy new year, my dear children!”

The first of January is, then, a day of kind wishes; of happy hopes; of bright anticipations: it is a day in which we feel at peace with all the world, and, if we have done our duty well during the departed year, we feel peaceful within.

Methinks I hear my young readers say, “Would that all our days might be thus cheerful and agreeable!” Alas! this may not be. It is not our lot to be thus cheerful and happy all the days of our lives. A part of our time must be devoted to study, to labor, to duty. We cannot always be enjoying holidays. And, indeed, it is not best we should. As people do not wish always to be eating cake and sugar-plums, so they do not always desire to be sporting and playing. As the cake and sugar-plums would, by and by, become sickening to the palate, so the play would at last grow tedious. As we should soon desire some good solid meat, so we should also desire some useful and instructive occupation.

But as it is now new year’s day, let us make the best of it. I wish you a happy new year, my black-eyed or blue-eyed reader! Nay, I wish you many a happy new year! and, what is more, I promise to do all in my power to make you happy, not only for this ensuing year, but for many seasons to come. And how do you think I propose to do it? That is what I propose to tell you!

In the first place, I am going to tell you, month by month, a lot of stories both useful and amusing. I wish to have a part of your time to myself, and, like my young friend Tom Stedfast, whose portrait I give you at the head of this article, I wish you not only to read my Magazine, but, if you have any little friends who cannot afford to buy it, I wish you to lend it to them, so that they may peruse it.

Tom is a rare fellow! No sooner does he get the Magazine than he sits down by the fire, just as you see him in the picture, and reads it from one end to the other. If there is anything he don’t understand, he goes to his father and he explains it. If there are any pretty verses, he learns them by heart; if there is any good advice, he lays it up in his memory; if there is any useful information, he is sure to remember it. Tom resembles a squirrel in the autumn, who is always laying up nuts for the winter season; for the creature knows that he will have need of them, then. So it is with Tom; when he meets with any valuable knowledge—it is like nuts to him—and he lays it up, for he is sure that he will have use for it at some future day. And there is another point in which Tom resembles the squirrel; the latter is as lively and cheerful in gathering his stores for future use, as he is in the spring time, when he has only to frisk and frolic amid the branches of the trees—and Tom is just as cheerful and pleasant about his books and his studies, as he is when playing blind-man’s-buff.

Now I should like to have my young readers as much like Tom Stedfast as possible; as studious, as fond of knowledge, and yet as lively and as good humored. And there is another thing in which I should wish all my young friends to resemble Tom; he thinks everything of me! No sooner does he see me stumping and stilting along, than he runs up to me, calling out, “How do you do, Mr. Merry? I’m glad to see you; I hope you are well! How’s your wooden leg?”

Beside all this, Tom thinks my Museum is first-rate—and I assure you it is a great comfort to my old heart, when [Pg 3] I find anybody pleased with my little Magazine. I do not pretend to write such big books as some people; nor do I talk so learnedly as those who go to college and learn the black arts. But what I do know, I love to communicate; and I am never so happy as when I feel that I am gratifying and improving young people. This may seem a simple business, to some people, for an old man; but if it gives me pleasure, surely no one has a right to grumble about it.

There is another thing in Tom Stedfast which I like. If he meets with anything in my Magazine which he does not think right, he sits down and writes me a letter about it. He does not exactly scold me, but he gives me a piece of his mind, and that leads to explanations and a good understanding. So we are the best friends in the world. And now what I intend to do is, to make my little readers as much like Tom Stedfast as possible. In this way I hope I may benefit them not only for the passing year, but for years to come. I wish not only to assist my friends in finding the right path, but I wish to accustom their feet to it, so that they may adopt good habits and continue to pursue it. With these intentions I enter upon the new year, and I hope that the friendship already begun between me and my readers, will increase as we proceed in our journey together.

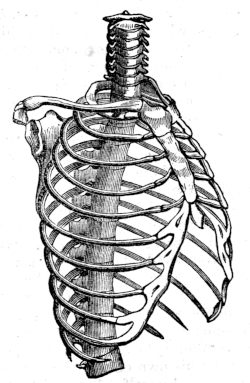

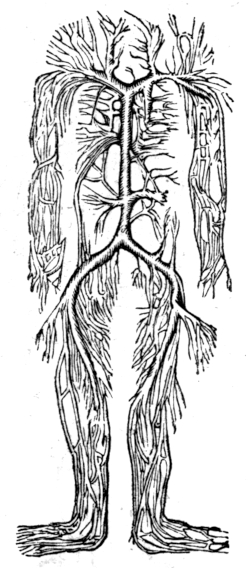

There are few things more curious, strange, and wonderful than the facts revealed by geology. This science is occupied with the structure of the surface of the earth; it tells us of the rocks, gravel, clay, and soil of which it is composed, and how they are arranged.

In investigating these materials, the geologists have discovered the bones of strange animals, imbedded either in the rocks or the soil, and the remains of vegetables such as do not now exist. These are called fossil remains; the word fossil meaning dug up. This subject has occupied the attention of many very learned men, and they have at last come to the most astonishing results. A gigantic skeleton has been found in the earth near Buenos Ayres, in South America; it is nearly as large as the elephant, its body being nine feet long and seven feet high. Its feet were enormous, being a yard in length, and more than twelve inches wide. They were terminated by gigantic claws; while its huge tail, which probably served as a means of defence, was larger than that of any other beast, living or extinct.

This animal has been called the Megatherium: mega, great, therion, wild beast. It was of the sloth species, and seems to have had a very thick skin, like that of the armadillo, set on in plates resembling a coat of armor. There are no such animals in existence now; they belong to a former state of this earth,—to a time before the creation of man.

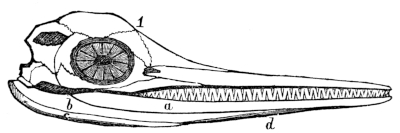

Discoveries have been made of the remains of many other fossil animals belonging to the ancient earth. One of them is called the Ichthyosaurus, or fish lizard. It had the teeth of a crocodile, the head of a lizard, and the fins or paddles of a whale. These fins, or paddles were very curious, and consisted of above a hundred small bones, closely united together. This animal used to live principally at the bottoms of rivers, and devour amazing quantities of fish, [Pg 4] and other water animals, and sometimes its own species; for an ichthyosaurus has been dug out of the cliffs at Lyme Regis, England, with part of a small one in his stomach. This creature was sometimes thirty or forty feet long.

The jaws of the Ichthyosaurus.

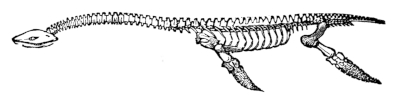

Another of these fossil animals is called the Plesiosaurus, a word which means, like a lizard. It appears to have formed an intermediate link between the crocodile and the ichthyosaurus. It is remarkable for the great length of its neck, which must have been longer than that of any living animal. In the engraving at the beginning of this number, you will see one of these animals swimming in the water. The following is a view of his skeleton; the creature was about fifteen feet long.

Skeleton of the Plesiosaurus.

But we have not yet mentioned the greatest wonder of fossil animals; this is the Iguanodon, whose bones have been found in England. It was a sort of lizard, and its thigh bones were eight inches in diameter. This creature must have been from seventy to a hundred feet long, and one of its thighs must have been as large as the body of an ox. I have given a portrait of this monster, drawn by Mr. Billings, an excellent young artist, whom you will find at No. 10, Court st., Boston. I cannot say that the picture is a very exact likeness; for as the fellow has been dead some thousands of years, we can only be expected to give a family resemblance. We have good reason to believe, however, that it is a tolerably faithful representation, for it is partly copied from a design by the celebrated John Martin, in London, and to be found in a famous book on the wonders of geology, by Mr. Mantel.

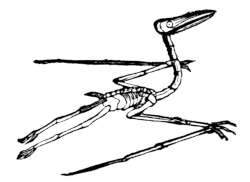

There was another curious animal, called the Pterodactyle, with gigantic wings. The skull of this animal must have been very large in proportion to the size of the skeleton, the jaws themselves being almost as large as its body.

Skeleton of the Pterodactyle.

They were furnished with sharp, hooked teeth. The orbits of the eyes were very large; hence it is probable [Pg 5] that it was a nocturnal animal, like the bat, which, at first sight, it very much resembles in the wings, and other particulars.

The word pterodactyle signifies wing-fingered; and, if you observe, you will find that it had a hand of three fingers at the bend of each of its wings, by which, probably, it hung to the branches of trees. Its food seems to have been large dragon-flies, beetles and other insects, the remains of some of which have been found close to the skeleton of the animal. The largest of the pterodactyles were of the size of a raven. One of them is pictured in the cut with the Iguanodon.

Another very curious animal which has been discovered is the Dinotherium, being of the enormous length of eighteen feet. It was an herbiferous animal, and inhabited fresh water lakes and rivers, feeding on weeds, aquatic roots, and vegetables. Its lower jaws measured four feet in length, and are terminated by two large tusks, curving downwards, like those of the upper jaw of the walrus; by which it appears to have hooked itself to the banks of rivers as it slept in the water. It resembled the tapirs of South America. There appear to have been several kinds of the dinotherium, some not larger than a dog. One of these small ones is represented in the picture with the Iguanodon.

The bones of the creatures we have been describing, were all found in England, France, and Germany, except those of the megatherium, which was found in South America. In the United States, the bones of an animal twice as big as an elephant, called the Mastodon, or Mammoth, have been dug up in various places, and a nearly perfect skeleton is to be seen at Peale’s Museum, in Philadelphia.

Now it must be remembered that the bones we have been speaking of, are found deeply imbedded in the earth, and that no animals of the kind now exist in any part of the world. Beside those we have mentioned, there were many others, as tortoises, elephants, tigers, bears, and rhinoceroses, but of different kinds from those which now exist.

It appears that there were elephants of many sizes, and some of them had woolly hair. The skeleton of one of the larger kinds, was found in Siberia, some years since, partly imbedded in ice, as I have told you in a former number.

The subject of which we are treating increases in interest as we pursue it. Not only does it appear, that, long before man was created, and before the present order of things existed on the earth, strange animals, now unknown, inhabited it, but that they were exceedingly numerous. In certain caves in England, immense quantities of the bones of hyenas, bears, and foxes are found; and the same is the fact in relation to certain caves in Germany.

Along the northern shores of Asia, the traces of elephants and rhinoceroses are so abundant as to show that these regions, now so cold and desolate, were once inhabited by thousands of quadrupeds of the largest kinds. In certain parts of Europe, the hills and valleys appear to be almost composed of the bones of extinct animals; and in all parts of the world, ridges, hills and mountains, are made up of the shells of marine animals, of which no living specimen now dwells on the earth!

Nor is this the only marvel that is revealed by the discoveries of modern geology. Whole tribes of birds and insects, whole races of trees and plants, have existed, and nothing is left of their story save the traces to be found in the soil, or the images depicted in the layers [Pg 6] of slate. They all existed before man was created, and thousands of years have rolled over the secret, no one suspecting the wonderful truth. Nor does the train of curiosities end here. It appears that the climates of the earth must have been different in those ancient and mysterious days from what they are at present: for in England, ferns, now small plants, grew to the size of trees, and vegetables flourished there of races similar to those which now grow only in the hot regions of the tropics.

As before stated, the northern shores of Siberia, in Asia, at present as cold and desolate as Lapland, and affording sustenance only to the reindeer that feeds on lichens, was once inhabited by thousands and tens of thousands of elephants, and other creatures, which now only dwell in the regions of perpetual summer.

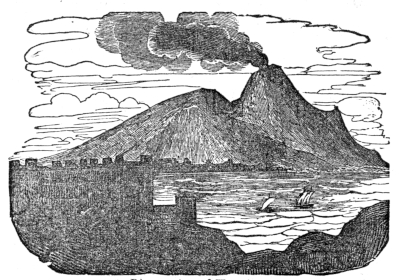

The inferences drawn from all these facts, which are now placed beyond dispute, are not only interesting, but they come upon us like a new revelation. They seem to assure us that this world in which we dwell has existed for millions of years; that at a period, ages upon ages since, there was a state of things totally distinct from the present. Europe was then, probably, a collection of islands. Where England now is, the iguanodon then dwelt, and was, probably, one of the lords of the soil.

This creature was from seventy to a hundred feet long. He dwelt along the rivers and lakes, and had for his companions other animals of strange and uncouth forms. Along the borders of the rivers the ferns grew to the height of trees, and the land was shaded with trees, shrubs, and plants, resembling the gorgeous vegetation of Central America and Central Africa.

This was one age of the world—one of the days in which the process of creation was going on. How long this earth remained in this condition, we cannot say, but probably many thousands of years. After a time, a change came over it. The country of the iguanodon sunk beneath the waters, and after a period, the land arose again, and another age began. Now new races of animals and vegetables appeared.

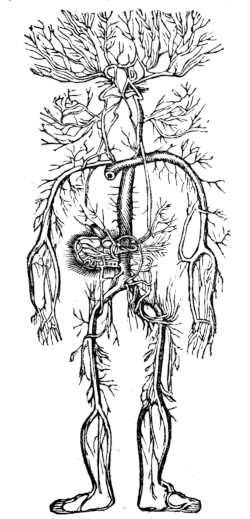

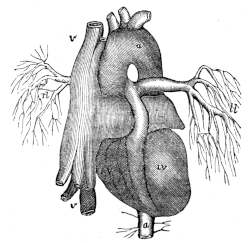

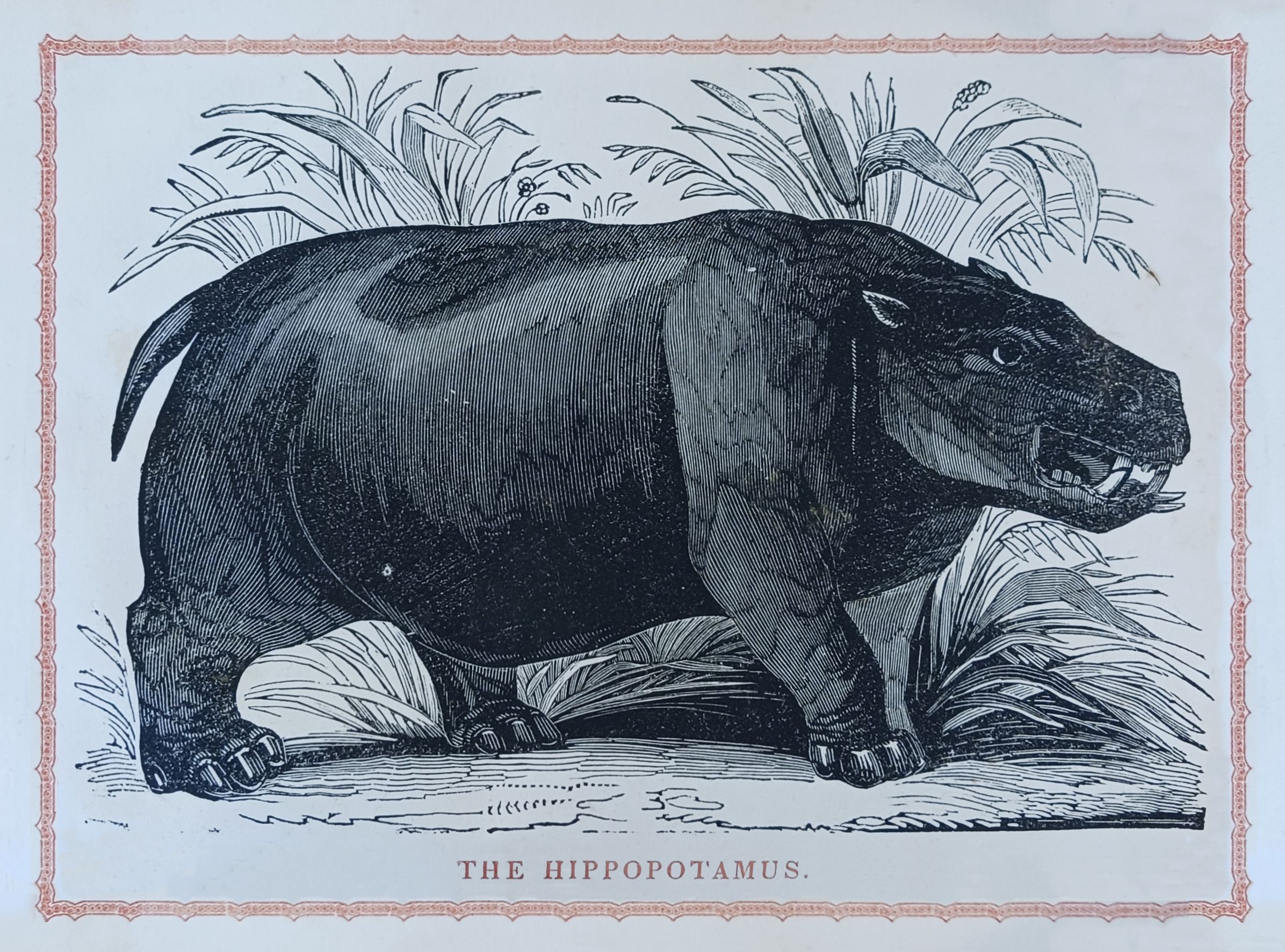

The waters teemed with nautili, and many species of shell and other fishes, at present extinct; the tropical forests had disappeared, and others took their places. Instead of the iguanodon, and the hideous reptiles that occupied the water and the land before, new races were seen. Along the rivers and marshes were now the hippopotamus, tapir, and rhinoceros; upon the land were browsing herds of deer of enormous size, and groups of elephants and mastodons, of colossal magnitude.

This era also passed away; these mighty animals became entombed in the earth; the vegetable world was changed; swine, horses and oxen were now seen upon the land, and man, the head of creation, spread over the earth, and assumed dominion over the animal tribes.

Such are the mighty results to which the researches of modern geology seem to lead us. They teach us that the six days, spoken of in the book of Genesis, during which the world was created, were probably not six days of twenty-four hours, but six periods of time, each of them containing thousands of years. They teach us also that God works by certain laws, and that even in the mighty process of creation, there is a plan, by which he advances in his work from one step to another, and always by a progress of improvement.

So far, indeed, is geology from furnishing evidence against the truth of the Bible, that it offers the most wonderful confirmation of it. No traces of the bones of man are found among [Pg 7] these remains of former ages, and thus we have the most satisfactory and unexpected evidence that the account given of his creation in the book of Genesis is true. It appears, also, that the present races of animals must have been created at the same time he was, for their bones do not appear among the ancient relics of which we have been speaking.

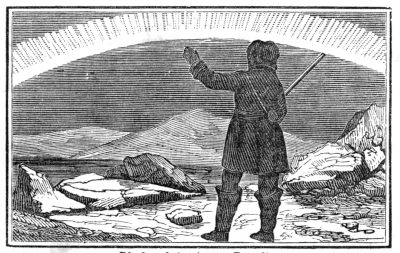

Linsk and the Aurora Borealis.

The respectability of bears.—A hunter’s story.—Yakootsk in sight.

While the travellers proceeded on their journey, Linsk, now thoroughly excited by the adventure with the wolves, seemed to have his imagination filled with the scenes of former days. In the course of his observations, he remarked that though he had a great respect for a wolf, he had a positive reverence for a bear.

“Indeed!” said Alexis, “how is it possible to have such a feeling as reverence for a wild beast, and one so savage as a bear? I never heard any good of the creature.”

“That may be,” said Linsk; “and yet what I say is all right and proper. If you never heard any good of a bear, then I can give you some information. Now there is a country far off to the east of Siberia, called Kamtschatka. It’s a terrible cold country, and the snow falls so deep there in winter, as to cover up the houses. The people are then obliged to dig holes under the snow from one house to another, and thus they live, like burrowing animals, till the warm weather comes and melts away their covering.

“Now what would the people do in such a country, if it were not for the bears? Of the warm skins of these creatures they make their beds, coverlets, [Pg 8] caps, gloves, mittens, and jackets. Of them they also make collars for their dogs that draw their sledges, and the soles of their shoes when they want to go upon the ice to spear seals; for the hair prevents slipping. The creature’s fat is used instead of butter; and when melted it is burnt instead of oil.

“The flesh of the bear is reckoned by these people as too good to be enjoyed alone; so, when any person has caught a bear, he always makes a feast and invites his neighbors. Whew! what jolly times these fellows do have at a bear supper! They say the meat has the flavor of a pig, the juiciness of whale-blubber, the tenderness of the grouse, and the richness of a seal or a walrus. So they consider it as embracing the several perfections of fish, flesh and fowl!

“And this is not all. Of the intestines of the bear, the Kamtschatdales make masks to shield the ladies’ faces from the effects of the sun; and as they are rendered quite transparent, they are also used for window-panes, instead of glass. Of the shoulder-blades of this creature, the people make sickles for cutting their grass; and of the skins they make muffs to keep the ladies’ fingers warm.

“Beside all this, they send the skins to market, and they bring high prices at St. Petersburgh, for the use of the ladies, and for many other purposes. Such is the value of this creature when dead; when alive he is also of some account. He has a rope put around his neck, and is taught a great many curious tricks. I suppose he might learn to read and go to college, as well as half the fellows that do go there; but of this I cannot speak with certainty, for I never went myself. All I can say is, that a well-taught bear is about the drollest creature that ever I saw. He looks so solemn, and yet is so droll! I can’t but think, sometimes, that there’s a sort of human nature about the beast, for there’s often a keen twinkle in his eye, which seems to say, ‘I know as much as the best of you: and if I don’t speak, it’s only because I scorn to imitate such a set of creatures as you men are!’

“It is on account of the amusement that bears thus afford, that these Kamtschatdales catch a good many living ones, and send them by ships to market. They also send live bears to St. Petersburgh, London, and Paris, for the perfumers. These people shut them up, and make them very fat, and then kill them for their grease. This is used by the fops and dandies to make their locks grow. I suppose they think that the fat will operate on them as it does on the bear, and give them abundance of hair. I’m told that in the great cities, now-a-days, a young man is esteemed in proportion as he resembles a bear in this respect. Accordingly bears’ grease is the making of a modern dandy, and so there’s a great demand for the creature that affords such a treasure.

“Now, master ’Lexis, I hope you are satisfied that in saying you never heard any good of a bear, you only betrayed ignorance—a thing that is no reproach to one so young as yourself. But, after all I’ve said, I havn’t half done. You must remember that this creature is not like a sheep, or a reindeer, or a cow, or a goat—always depending upon man for breakfast, dinner and supper. Not he, indeed! He is too independent for that; so he supports himself, instead of taxing these poor Kamtschatdales for his living. Why, they have to work half the year to provide food for their domestic animals the other half; whereas the bear feeds and clothes himself, and when they want his skin, his flesh, or his carcass—why, he is all ready for them!”

“I am satisfied,” said Alexis “that [Pg 9] the bear is a most valuable creature to those people who live in cold, northern countries; for he seems to furnish them with food, dress, and money; but, after all, they have the trouble of hunting him!”

“Trouble!” said Linsk; “why, lad, that’s the best of it all!”

“But isn’t it dangerous?” said Alexis.

“Of course it is,” replied the old hunter; “but danger is necessary to sport. It is to hunting, like mustard to your meat, or pepper and vinegar to your cabbage. Danger is the spice of all adventure; without this, hunting would be as insipid as ploughing. There is danger in hunting the bear; for though he’s a peaceable fellow enough when you let him alone, he’s fierce and furious if you interfere with his business, or come in his way when he’s pinched with hunger.

“I’ve had some adventures with bears myself, and I think I know the ways of the beast as well as anybody. Sometimes he’ll trot by, only giving you a surly look or a saucy growl. But if you chance to fall upon a she bear, with a parcel of cubs about her, why then look out.”

“Did you ever see a bear with cubs, father?” said Nicholas, the elder of Linsk’s sons.

“To be sure I have,” was the answer.

“Well, what I want to know, father,” said the boy, “is, whether they are such creatures as people say. I’ve been told that young cubs are as rough as a bramble bush, and that they don’t look like anything at all till the old bear has licked them into shape. Is that true?”

“No, no—it’s all gammon, Nick. Young cubs are the prettiest little things you ever saw. They are as soft and playful as young puppies; and they seem by nature to have a true Christian spirit. It’s as the creature grows old that he grows wicked and savage—and I believe it’s the same with men as with bears.

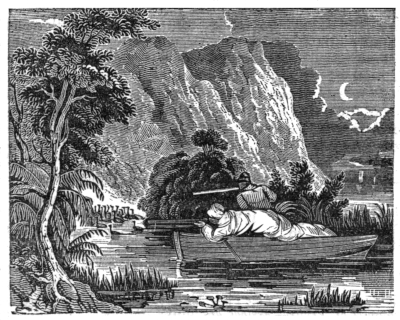

“I remember that once, when I was a young fellow, I was out with a hunting party in search of sables. Somehow or other I got separated from my companions, and I wandered about for a long time, trying in vain to find them. At last night came on, and there I was, alone! This happened far to the north, in the country of the Samoides. It was mid-winter, and though the weather was clear, it was bitter cold. I walked along upon the snow-crust, and, coming to an open space, I called aloud and discharged my gun. I could hear the echoes repeating my words, and the cracking of my piece, but there was no answer from my friends. It was all around as still as death, and even the bitter blast that made my whole frame tingle, glided by without a whisper or a sigh. There were no people in all the country round about: and, I must confess that such a sense of desertion and desolation came over me, as almost made my heart sink within me.

“I remember it was one of those nights when the ‘northern lights’ shone with great brilliancy—a thing that often occurs in those cold countries. At first there was an arch of light in the north, of a pure and dazzling white. By and by, this began to shoot upward, and stream across the heavens, and soon the rays were tinged with other hues. At one time I saw a vast streak, seemingly like a sword of flame, piercing the sky; suddenly this vanished, and a mighty range of castles and towns, some white, some red, and some purple, seemed set along the horizon. In a few seconds these were changed, and now I saw a thing like a ship, with sails of many colors. This, too, disappeared, and then I saw images like giants dancing in the [Pg 10] sky. By and by their sport was changed for battle, and it seemed as if they were fighting with swords of flame and javelins of light!

“I watched this wonderful display for some time, and at first I thought it boded some dreadful harm to me. But after a little reflection, I concluded that such vast wonders of nature, could not be got up on account of a poor young sable-hunter, and so I went on my way. Leaving the open country, I plunged into the forest, and among the thick fir trees began to seek some cave or hollow log, where I might screen myself from the bitter blast.

“While I was poking about, I saw four little black fellows playing like kittens, on the snow-crust, at a short distance. I gazed at them for a moment, and soon discovered that they were young bears. They were each of the size of a cat, and never did I see anything more playful than they were. I stood for some time watching them, and they seemed very much like so many shaggy puppies, all in a frolic.

“Well, I began to think what it was best to do; whether to make an attack, or drive them to their den, and take a night’s lodging with them. I was in some doubt how they would receive a stranger, while their mamma was not at home; but I concluded, on the whole, to throw myself upon their hospitality—for I was shivering with cold, and the idea of getting into a warm bed with these clever fellows, was rather inviting just then. So I walked forward and approached the party. They all rose up on their hind legs and uttered a gruff growl, in token of astonishment. Never did I behold such amazement as these creatures displayed. I suppose they had never seen a man before, and they appeared mightily puzzled to make out what sort of a creature I was.

“Having looked at me for some time, the whole pack scampered away, and at a short distance entered a cave. I followed close upon them, and, coming to their retreat, was rejoiced to find that it was a hollow in a rock, the entrance of which was just large enough for me to creep in. In I went, though it was dark as a pocket. I knew that the old bear must be abroad, and as for the young ones, I was willing to trust them; for, as I said before, all young creatures seem to be civil till they have cut their eye teeth and learnt the wicked ways of the world.

“When I got into the cave, I felt round and found that it was about five feet square, with a bed of leaves at the bottom. The young bears had slunk away into the crevices of the rock, but they seemed to offer no resistance. I found the place quite comfortable, and was beginning to think myself very well off, when the idea occurred to me, that madame bear would be coming home before long, and was very likely to consider me an intruder, and to treat me accordingly. These thoughts disturbed me a good deal, but at last I crept out of the cave, and gathered a number of large sticks; I then went in again and stopped up the entrance by wedging the sticks into it as forcibly as could. Having done this, and laying my gun at my side, I felt about for my young friends. I pretty soon got hold of one of them, and, caressing him a little, pulled him toward me. He soon snugged down at my side, and began to lick my hands. Pretty soon another crept out of his lurking-place, and came to me, and in a short time they were all with me in bed.

“I was soon very warm and comfortable, and after a short space the whole of us were in a sound snooze. How long we slept I cannot tell; but I was awakened by a terrible growl at the mouth of the cave, and a violent twitching [Pg 11] and jerking of the sticks that I had jammed into the entrance. I was not long in guessing at the true state of the case. The old bear had come back, and her sharp scent had apprized her that an interloper had crept into her bed-room. St. Nicholas! how she did roar, and how the sticks did fly! One after another was pulled away, and in a very short space of time, every stick was pulled out but one. This was the size of my leg, and lay across the door of the cave. I got hold of it and determined that it should keep its place. But the raging beast seized it with her teeth, and jerked it out of my hands in a twinkling. The entrance was now clear, and, dark as it was, I immediately saw the glaring eyeballs of the bear, as she began to squeeze herself into the cave. She paused a moment, and, fixing her gaze on me, uttered the most fearful growl I ever heard in my life. I don’t think I shall ever forget it, though it happened when I was a stripling—and that is some thirty years ago.

“Well, it was lucky for me that the hole was very small for such a portly creature; and, mad as she was, she had to scratch and squirm to get into the cave. All this time I was on my knees, gun in hand, and ready to let drive when the time should come. Poking the muzzle of my piece right in between the two balls of fire, whang it went! I was stunned with the sound, and kicked over beside. But I got up directly, and stood ready for what might come next. All was still as death; even the cubs, that were now lurking in the fissures of the rocks, seemed hushed in awful affright.

“As soon as my senses had fully returned, I observed that the fiery eyeballs were not visible, and, feeling about with my gun, I soon discovered that the bear seemed to be lifeless, and wedged into the entrance of the cave. I waited a while to see if life had wholly departed, for I was not disposed to risk my fingers in the mouth even of a dying bear; but, finding that the creature was really dead, I took hold of her ears, and tried to pull her out of the hole. But this was a task beyond my strength. She was of enormous size and weight, and, beside, was so jammed into the rocks as to defy all my efforts to remove the lifeless body.

“‘Well,’ thought I, ‘this is a pretty kettle of fish! Here I am in a cave, as snug as a fly in a bottle, with a bear for a cork! Who ever heard of such a thing before!’ What would have been the upshot I cannot say, had not unexpected deliverance been afforded me. While I was tugging and sweating to remove the old bear, I heard something without, as if there were persons near the cave. By and by the creature began to twitch, and at last out she went, at a single jerk. I now crept out myself—and behold, my companions were there!

“I need not tell you that it was a happy meeting. We made a feast of the old bear, and spent some days at the cave, keeping up a pleasant acquaintance with the young cubs. When we departed we took them with us, and they seemed by no means unwilling to go. We had only to carry one, and the rest followed. But look here, my boys! this is the river Lena, and yonder is Yakootsk. Soon we shall be there!”

(To be continued.)

A shop-keeper in New York, the other day, stuck upon his door the following laconic advertisement: “A boy wanted.” On going to his shop, the next morning, he beheld a smiling urchin in a basket, with the following pithy label: “Here it is.”

Emigration to Utica.—An expedition.—The salamander hat.—A terrible threat.—A Dutchman’s hunt for the embargo on the ships.—Utica long ago.—Interesting story of the Seneca chief.

I have now reached a point when the events of my life became more adventurous. From this time forward, at least for the space of several years, my history is crowded with incidents; and some of them are not only interesting to myself, but I trust their narration may prove so to my readers.

When I was about eighteen years of age, I left Salem for the first time since my arrival in the village. At that period there were a good many people removing from the place where I lived, and the vicinity, to seek a settlement at Utica. That place is now a large city, but at the time I speak of, about five and thirty years ago, it was a small settlement, and surrounded with forests. The soil in that quarter was, however, reputed to be very rich, and crowds of people were flocking to the land of promise.

Among others who had made up their minds to follow the fashion of that day, was a family by the name of Stebbins, consisting of seven persons. In order to convey these, with their furniture, it was necessary to have two wagons, one of which was to be driven by Mat Olmsted, and, at my earnest solicitation, my uncle consented that I should conduct the other.

After a preparation of a week, and having bade farewell to all my friends, Raymond, Bill Keeler, and my kind old uncle, and all the rest, we departed. Those who are ignorant of the state of things at that day, and regard only the present means of travelling, can hardly conceive how great the enterprise was esteemed, in which I was now engaged. It must be remembered that no man had then even dreamed of a rail-road or a steamboat. The great canal, which now connects Albany with Buffalo, was not commenced. The common roads were rough and devious, and instead of leading through numerous towns and villages, as at the present day, many of them were only ill-worked passages through swamps and forests. The distance was about two hundred miles—and though it may now be travelled in twenty hours, it was esteemed, for our loaded wagons, a journey of two weeks. Such is the mighty change which has taken place, in our country, in the brief period of thirty-five years.

I have already said that Mat Olmsted was somewhat of a wag; he was, also, a cheerful, shrewd, industrious fellow, and well suited to such an expedition. He encountered every difficulty with energy, and enlivened the way by his jokes and his pleasant observations.

It was in the autumn when we began our journey, and I remember one evening, as we had stopped at a tavern, and were sitting by a blazing fire, a young fellow came in with a new hat on. It was very glossy, and the youth seemed not a little proud of it. He appeared also to be in excellent humor with himself, and had, withal, a presuming and conceited air. Approaching where Mat was sitting, warming himself by the fire, the young man shoved him a little aside, saying, “Come, old codger, can’t you make room for your betters?”

“To be sure I can for such a handsome gentleman as yourself,” said Mat, good naturedly; he then added, “That’s a beautiful hat you’ve got on, mister; it looks like a real salamander!”

“Well,” said the youth, “it’s a pretty good hat, I believe; but whether it’s a salamander, or not, I can’t say.”

“Let me see it,” said Olmsted; and, [Pg 13] taking it in his hand, he felt of it with his thumb and finger, smelt of it, and smoothed down the fur with his sleeve. “Yes,” said he, at length, “I’ll bet that’s a real salamander hat; and if it is you may put it under that forestick, and it won’t burn any more than a witch’s broomstick.”

“Did you say you would bet that it’s a salamander hat?” said the young man.

“To be sure I will,” said Mat; “I’ll bet you a mug of flip of it; for if there ever was a salamander hat, that’s one. Now I’ll lay that if you put it under the forestick, it won’t singe a hair of it.”

“Done!” said the youth, and the two having shaken hands in token of mutual agreement, the youth gave his hat to Olmsted, who thrust it under the forestick. The fire was of the olden fashion, and consisted of almost a cartload of hickory logs, and they were now in full blast. The people in the bar-room, attracted by the singular wager, had gathered round the fire, to see the result of the experiment. In an instant the hat was enveloped by the flames, and in the course of a few seconds it began to bend and writhe, and then curled into a scorched and blackened cinder.

“Hulloo!” said Mat Olmsted, seizing the tongs and poking out the crumpled relic from the bed of coals, at the same time adding, with well-feigned astonishment, “Who ever did see the like of that! it wasn’t a salamander, arter all! Well, mister, you’ve won the bet. Hulloo, landlord, give us a mug of flip.”

The force of the joke soon fell upon the conceited young man. He had indeed won the wager—but he had lost his hat! At first he was angry, and seemed disposed to make a personal attack upon the cause of his mortification; but Matthew soon cooled him down. “Don’t mind it, my lad,” said he; “it will do you good in the long run. You are like a young cockerel, that is tickled with his tall red comb, and having had it pecked off, is ever after a wiser fowl. Take my advice, and if you have a better hat than your neighbors, don’t think that it renders you better than they. It’s not the hat, but the head under it, that makes the man. At all events, don’t be proud of your hat till you get a real salamander!”

This speech produced a laugh at the expense of the coxcomb, and he soon left the room. He had suffered a severe rebuke, and I could hardly think that my companion had done altogether right; and when I spoke to him afterward, he seemed to think so himself. He, however, excused what he had done, by saying that the fellow was insolent, and he hoped the lesson would be useful to him.

We plodded along upon our journey, meeting with no serious accident, and in the course of five or six days we were approaching Albany. Within the distance of a few miles, Matthew encountered a surly fellow, in a wagon. The path was rather narrow, and the man refused to turn out and give half the road. High words ensued, and, finally, my friend, brandishing his whip, called out aloud, “Turn out, mister; if you don’t, I’ll sarve you as I did the man back!”

The wagoner was alarmed at this threat, and turning out, gave half the road. As he was passing by, he had some curiosity to know what the threat portended; so he said, “Well, sir, how did you serve the man back?” “Why,” said Matthew, smiling, “I turned out myself!” This was answered by a hearty laugh, and after a few pleasant words between the belligerent parties, they separated, and we pursued our journey.

Albany is now a large and handsome [Pg 14] city; but at the time I speak of, it contained but about three thousand people, a very large part of whom were Dutch, and who could not speak much English. None of the fine streets and splendid public buildings, which you see there now, were in existence then. The streets were narrow and dirty, and most of the houses were low and irregular, with steep roofs, and of a dingy color. Some were built of tiles, some of rough stones, some of wood, and some of brick. But it was, altogether, one of the most disagreeable looking places I ever saw.

We remained there but a few hours. Proceeding on our journey, we soon reached Schenectady, which we found to be a poor, ill-built, Dutch village, though it is a handsome town now. We stopped here for the night; and, a little while after we arrived, a man with a wagon, his wife and three children, arrived also at the tavern. He was a Dutchman, and seemed to be in very ill-humor. I could hardly understand what he said, but by a little help from Matthew, I was able to make out his story.

You must know that Congress had passed a law forbidding any ships to go to sea; and this was called an embargo. The reason of it was, that England had treated this country very ill; and so, to punish her, this embargo was laid on the ships, to prevent people from carrying flour and other things to her, which she wanted very much; for many of her people were then engaged in war, and they could not raise as much grain as they needed.

Well, the old Dutchman had heard a great deal about the embargo on the ships; for the two parties, the democrats and federalists, were divided in opinion about it, and accordingly it was the subject of constant discussion. I remember that wherever we went, all the people seemed to be talking about the embargo. The democrats praised it as the salvation of the country, and the federalists denounced it as the country’s ruin. Among these divided opinions, the Dutchman was unable to make up his mind about it, accordingly, he hit upon an admirable method to ascertain the truth, and satisfy his doubts. He tackled his best horses to the family wagon, and, taking his wife and three children, travelled to Albany to see the embargo on the ships!

Well, he drove down to the water’s edge, and there were the vessels, sure enough; but where was the embargo? He inquired first of one man, and then of another, “Vare is de embargo? I vish to see de embargo vat is on de ships!” What he expected to see I cannot tell; but he had heard so much said about it, and it was esteemed, by one party at least, the cause of such multiplied evils, that he, no doubt, supposed the embargo must be something that could be seen and felt. But all his inquiries were vain. One person laughed at him, another snubbed him as an old fool, and others treated him as a maniac. At last he set out to return, and when he arrived at the tavern in Schenectady, he was not only bewildered in his mind, but he was sorely vexed in spirit. His conclusion was, that the embargo was a political bugbear, and that no such creature actually existed!

We set out early the next morning, and by dint of plodding steadily on through mud and mire, we at last reached the town of Utica, having been fourteen days in performing the journey from Salem. We found the place to contain about a thousand people, all the houses being of wood, and most of them built of logs, in the fashion of the log cabin. The town, however, had a bustling and thriving appearance, notwithstanding that the stumps of the forest were still standing in the streets.

[Pg 15] I noticed a great many Indians about the town, and soon learned that they consisted of the famous tribes called the Six Nations. Some of these are still left in the state of New York, but they have dwindled down to a very small number. But at the time I speak of, they consisted of several thousands, and were still a formidable race. They were at peace with the White people, and seemed to see their hunting grounds turned into meadows and wheat fields, with a kind of sullen and despairing submission.

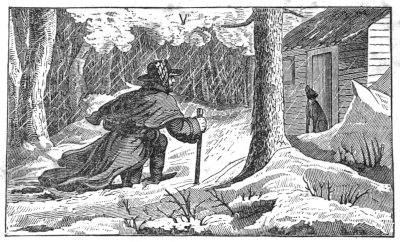

One of the first settlers in this vicinity was Judge W., who established himself at Whitestown—about four miles from Utica. This took place nearly a dozen years before my visit. He brought his family with him, among whom was a widowed daughter with an only child—a fine boy of four years old. You will recollect that the country around was an unbroken forest, and that this was the domain of the savage tribes.

Judge W. saw the necessity of keeping on good terms with the Indians, for as he was nearly alone, he was completely at their mercy. Accordingly he took every opportunity to assure them of his kindly feelings, and to secure good-will in return. Several of the chiefs came to see him, and all appeared pacific. But there was one thing that troubled him; an aged chief of the Seneca tribe, and one of great influence, who resided at the distance of half a dozen miles, had not yet been to see him; nor could he, by any means, ascertain the views and feelings of the sachem, in respect to his settlement in that region. At last he sent him a message, and the answer was, that the chief would visit him on the morrow.

True to his appointment the sachem came. Judge W. received him with marks of respect, and introduced his wife, his daughter, and the little boy. The interview that followed was deeply interesting. Upon its result, the judge conceived that his security might depend, and he was, therefore, exceedingly anxious to make a favorable impression upon the distinguished chief. He expressed to him his desire to settle in the country; to live on terms of amity and good fellowship with the Indians; and to be useful to them by introducing among them the arts of civilization.

The chief heard him out, and then said, “Brother, you ask much, and you promise much. What pledge can you give me of your good faith?”

“The honor of a man that never knew deception,” was the reply.

“The white man’s word may be good to the white man, yet it is but wind when spoken to the Indian,” said the sachem.

“I have put my life into your hands,” said the judge; “is not this an evidence of my good intentions? I have placed confidence in the Indian, and I will not believe that he will abuse or betray the trust that is thus reposed.”

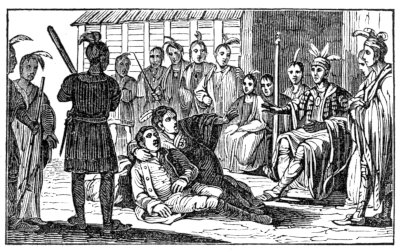

“So much is well,” replied the chief; “the Indian will repay confidence with confidence; if you will trust him he will trust you. But I must have a pledge. Let this boy go with me to my wigwam; I will bring him back in three days with my answer!”

If an arrow had pierced the bosom of the mother, she could not have felt a keener pang than went to her heart, as the Indian made this proposal. She sprung from her seat, and rushing to the boy, who stood at the side of the sachem, looking into his face with pleased wonder and admiration; she encircled him in her arms, and pressing him close to her bosom, was about to fly from the room. A gloomy and ominous frown came over the sachem’s brow, but he did not speak.

But not so with Judge W. He knew [Pg 16] that the success of their enterprise, the very lives of his family, depended upon the decision of the moment. “Stay, stay, my daughter!” said he. “Bring back the boy, I beseech you. He is not more dear to you than to me. I would not risk the hair of his head. But, my child, he must go with the chief. God will watch over him! He will be as safe in the sachem’s wigwam as beneath our roof and in your arms.”

The agonized mother hesitated for a moment; she then slowly returned, placed the boy on the knee of the chief, and, kneeling at his feet, burst into a flood of tears. The gloom passed from the sachem’s brow, but he said not a word. He arose, took the boy in his arms and departed.

I shall not attempt to describe the agony of the mother for the three ensuing days. She was agitated by contending hopes and fears. In the night she awoke from sleep, seeming to hear the screams of her child calling upon its mother for help! But the time wore away—and the third day came. How slowly did the hours pass! The morning waned away; noon arrived; and the afternoon was now far advanced; yet the sachem came not. There was gloom over the whole household. The mother was pale and silent, as if despair was settling coldly around her heart. Judge W. walked to and fro, going every few minutes to the door, and looking through the opening in the forest toward the sachem’s abode.

At last, as the rays of the setting sun were thrown upon the tops of the forest around, the eagle feathers of the chieftain were seen dancing above the bushes in the distance. He advanced rapidly, and the little boy was at his side. He was gaily attired as a young chief—his feet being dressed in moccasins; a fine beaver skin was over his shoulders, and eagles’ feathers were stuck into his hair. He was in excellent spirits, and so proud was he of his honors, that he seemed two inches taller than before. He was soon in his mother’s arms, and in that brief minute, she seemed to pass from death to life. It was a happy meeting—too happy for me to describe.

“The white man has conquered!” said the sachem; “hereafter let us be friends. You have trusted the Indian; he will repay you with confidence and friendship.” He was as good as his word; and Judge W. lived for many years in peace with the Indian tribes, and succeeded in laying the foundation of a flourishing and prosperous community.

A certain farmer reared with his own hands a row of noble fruit trees. To his great joy they produced their first fruit, and he was anxious to know what kind it was.

And the son of his neighbor, a bad boy, came into the garden, and enticed the young son of the farmer, and they went and robbed all the trees of their fruit before it was fully ripe.

When the owner of the garden came and saw the bare trees, he was very much grieved, and cried, Alas! why has this been done? Some wicked boys have destroyed my joy!

This language touched the heart of the farmer’s son, and he went to his companion, and said, Ah! my father is grieved at the deed we have committed. I have no longer any peace in my mind. My father will love me no more, but chastise me in his anger, as I deserve.

But the other answered, You fool, your father knows nothing about it, and will never hear of it. You must carefully conceal it from him, and be on your guard.

[Pg 17] And when Henry, for this was the name of the boy, came home, and saw the smiling countenance of his father, he could not return his smile; for he thought, how can I appear cheerful in the presence of him whom I have deceived? I cannot look at myself. It seems as if there were a dark shade in my heart.

Now the father approached his children, and handed every one some of the fruit of autumn, Henry as well as the others. And the children jumped about delighted, and ate. But Henry concealed his face, and wept bitterly.

Then the father began, saying, My son, why do you weep?

And Henry answered, Oh! I am not worthy to be called your son. I can no longer bear to appear to you otherwise than what I am, and know myself to be. Dear father, manifest no more kindness to me in future, but chastise me, that I may dare approach you again, and cease to be my own tormentor. Let me severely atone for my offence, for behold, I robbed the young trees!

Then the father extended his hand, pressed him to his heart, and said, I forgive you, my child! God grant that this may be the last, as well as the first time, that you will have any action to conceal. Then I will not be sorry for the trees.

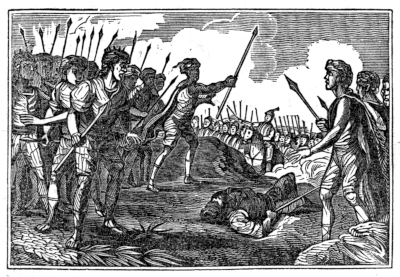

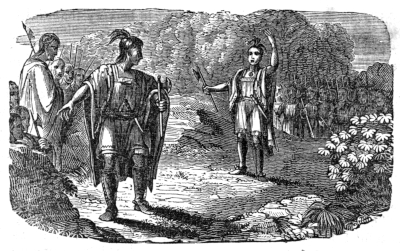

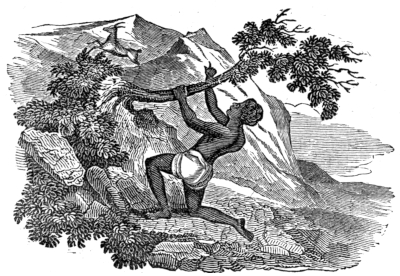

Santaro leading the Araucanians to battle.

Chili continued.—The Araucanians attack the Spaniards.—Valdivia, the Spanish general, enters the territory of the Republic.—Founds cities.—Is defeated and slain.—The Spaniards are driven from the country.—Santaro slain.

In the preceding chapter, I have given an account of the customs and manners of that nation in Chili called Araucanians. The country inhabited by this brave nation is one of the finest in South America. It lies on the seacoast, and is calculated to be 186 miles in length, and its breadth from the sea to the Andes is over 300 miles.

But it is not the size of territory, or [Pg 18] its fertility, or beautiful climate which excites our interest; it is the character and the deeds of a free and noble-spirited people, fighting for their homes and country. I shall briefly recount their wars with the Spaniards, from the time of the first battle in 1550, till the time when the Spaniards were completely driven from the Araucanian territory, in 1692.

The first battle was fought in the country of the Pemones, a nation occupying the north bank of the Biobio, a river which separates the Araucanian territory from the other nations of Chili. The Araucanians, finding the Spaniards had conquered all that part of Chili which had been subjected to Peru, and were advancing towards their province, did not wait to be invaded, but boldly marched to seek the white men.

Valdivia commanded the Spanish forces; he had been in many battles in Europe as well as America, but he declared that he had never before been in such imminent danger. The Araucanians rushed on, without heeding the musketry, and fell at once upon the front and flanks of the Spanish army.

The victory was long doubtful; and though the Araucanians lost their chief, and finally withdrew from the field, the Spaniards were in no condition to follow them.

Not in the least discouraged, the brave Indians collected another army, and chose a new toqui, named Lincoyan. This commander was a great man in size, and had the show of being brave, but he was not so; and during the time he held the office of toqui, no battle of consequence was fought with the Spaniards.

Valdivia soon improved these advantages. He advanced into the Araucanian country, and founded a city on the shores of the Canten, a river that divides the republic into two nearly equal parts. It was a beautiful place, and abounded with every convenience of life. The Spaniards felt highly gratified with their success. Valdivia called the name of their new city Imperial, and he prepared to divide the country among his followers, as Pizarro had divided Peru. Valdivia gave to Villagran, his lieutenant-general, the province of Maquegua, called by the Araucanians the key of their country, with thirty thousand inhabitants. The other officers had also large shares.

Valdivia received reinforcements from Peru, and he continued to advance, and, in a short time, founded a second city, which he named from himself, Valdivia; and then a third, which he called the City of the Frontiers. He also built a number of fortresses, and so skilfully disposed his forces that he thought the people were completely subdued. He did not gain all these advantages without great exertions. He was often engaged in battles with the Indians, but the toqui was a timid and inefficient commander, and the spirit of the brave Araucanians seemed to have forsaken them.

However, men who have been accustomed to freedom, are not easily reduced to that despair which makes them peaceable slaves. The Araucanians at length roused themselves, and appointed a new toqui. There was an old man, named Colocolo, who had long lived in retirement, but his country’s wrongs and danger impelled him to action. He traversed the provinces, and exhorted the people to choose a new toqui. They assembled, and, after a stormy debate, they requested Colocolo to name the toqui. He appointed Caupolicon, ulmen of Tucupel.

He was a man of lofty stature, uncommon bodily strength, and the majesty of his countenance, though he had lost one eye, was surpassing. The [Pg 19] qualities of his mind were as superior as his personal appearance. He was a serious, patient, sagacious, and valiant man, and the nation applauded the choice of Colocolo.

Having assumed the axe, the badge of his authority, Caupolicon appointed his officers, and soon marched with a large army to drive the Spaniards from the country. He took and destroyed the fortress of Arauco, and invested that of Tucupel. Valdivia, hearing of this, assembled his troops and marched against the Indians. He had about two hundred Spaniards and five thousand Indian auxiliaries, Promancians and Peruvians, under his command. Caupolicon had about ten thousand troops.

The two armies met on the third of December, 1553. The fight was desperate and bloody. The Spaniards had cannon and musketry—but the brave Araucanians were on their own soil, and they resolved to conquer or die. As fast as one line was destroyed, fresh troops poured in to supply the places of the slain. Three times they retired beyond the reach of the musketry, and then, with renewed vigor, returned to the attack.

At length, after the loss of a great number of their men, they were thrown into disorder, and began to give way. At this momentous crisis, a young Araucanian, named Santaro, of sixteen years of age, grasping a lance, rushed forward, crying out, “Follow me, my countrymen! victory courts our arms!” The Araucanians, ashamed at being surpassed by a boy, turned with such fury upon their enemies, that at the first shock they put them to rout, cutting in pieces the Spaniards and their Indian allies, so that of the whole army only two of the latter escaped. Valdivia was taken prisoner. Both Caupolicon and Santaro intended to spare his life, and treat him kindly, but while they were deliberating on the matter, an old ulmen, of great authority in the country, who was enraged at the perfidy and cruelty the Spaniards had practised on the Indians, seized a club, and, at one blow, killed the unfortunate prisoner. He justified the deed by saying that the Christian, if he should escape, would mock at them, and laugh at his oaths and promises of quitting Chili.

The Araucanians held a feast and made great rejoicings, as well they might, on account of their victory. After these were over, Caupolicon took the young Santaro by the hand, presented him to the national assembly, and, after praising him for his bravery and patriotism in the highest terms, he appointed the youth lieutenant-general extraordinary, with the privilege of commanding in chief another army, which was to be raised to protect the frontiers from the Spaniards. This was a great trust to be committed to a youth of sixteen.

The Spaniards were overwhelmed with their misfortunes, and, dreading the approach of the Indians, they abandoned all the places and fortified posts, except the cities of Imperial and Valdivia, which had been established in the Araucanian country. Caupolicon immediately besieged these two places, committing to Santaro the duty of defending the frontier.

In the meantime the two soldiers who escaped from the battle, fled to the Spanish cities established in the Promancian territory, and roused them to attempt another expedition. Francis Villegran was appointed commander, to succeed Valdivia, and an army of Spaniards and their Indian allies soon began their march for Arauco.

Villegran crossed the Biobio without opposition, but immediately on entering the passes of the mountains he was attacked [Pg 20] by the Indian army under Santaro. Villegran had six pieces of cannon, and a strong body of horse, and he thought, by the aid of them, he could force the passage. He directed an incessant fire of cannon and musketry to be kept up; the mountain was covered with smoke, and resounded with the thunder of the artillery and the whistling of bullets. Santaro, in the midst of this confusion, firmly maintained his post; but finding that the cannon was sweeping down his ranks, he directed one of his bravest captains to go with his company, and seize the guns. “Execute my order,” said, the young Santaro, “or never again come into my presence!”

The brave Indian and his followers rushed with such violence upon the corps of artillery, that the Spanish soldiers were all either killed or captured, and the cannon brought off in triumph to Santaro. In fine, the Araucanians gained a complete victory. Of the Europeans and their Indian allies, three thousand were left dead upon the field, and Villegran himself narrowly escaped being taken prisoner. The city of Conception fell into the hands of Santaro, who, after securing all the booty, burned the houses and razed the citadel to its foundation.

These successes stimulated the young chief, Santaro, to carry the war into the enemy’s country. Collecting an army of six hundred men, he marched to the attack of Santiago, a city which the Spaniards had founded in the Promancian territory, more than three hundred miles from the Araucanians. Santaro reached Santiago, and in several battles against the Spaniards was victorious; but, at length, betrayed by a spy, he was slain in a skirmish with the troops of Villegran; and his men, refusing to surrender to those who had slain their beloved general, fought, like the Spartans, till every Araucanian perished! The Spaniards were so elated with their victory, that they held public rejoicings for three days at Santiago.

But the memory of Santaro did not perish with his life. He was long deeply lamented by his countrymen, and his name is still celebrated in the heroic songs of his country, and his actions proposed as the most glorious model for the imitation of their youth. Nor did the Spaniards withhold their tribute of praise to the brave young patriot. They called him the Chilian Hannibal.

“It is not just,” said a celebrated Spanish writer, “to depreciate the merit of the American Santaro, that wonderful young warrior, whom, had he been ours, we should have elevated to the rank of a hero.”

But the history of battles and sieges, all having the same object,—on the part of the Spaniards that of conquest, on the part of the Araucanians the preservation of their liberties and independence,—will not be profitable to detail. Suffice it to say, that from the fall of Santaro in 1556, till peace was finally established between the Spaniards and Araucanians in 1773, a series of battles, stratagems, and sieges, are recorded, which, on the part of the Araucanians, were sustained with a perseverance and power, such as no other of the Indian nations in America have ever displayed. Nor were their victories stained with cruelty or revenge.

The Spaniards obtained many triumphs over the haughty freemen; and I regret to say that they did not use their advantages in the merciful spirit of Christianity. Probably, if they had done so, they might have maintained their authority. But the Spaniards went to America to gain riches; they indulged their avaricious propensities till every kind and generous feeling of humanity seems to have been extinguished [Pg 21] in their hearts. An excessive desire to be rich, if cherished and acted upon as the chief purpose of life, is the most degrading passion indulged by civilized man; it hardens the heart, and deadens or destroys every generous emotion, till the cold, cruel, selfish individual would hardly regret to see his species annihilated, if by that means he might be profited. The cannibal, who feeds on human flesh, is hardly more to be abhorred, than the civilized man who, on human woes, feeds his appetite for riches!

But the Spaniards gained nothing from the Araucanians. After a contest of nearly one hundred and fifty years, and at the cost of more blood and treasure than all their other possessions in South America had demanded, the Spaniards were glad to relinquish all claim to the territory of these freemen, only stipulating that the Indians should not make incursions into that part of Chili which lies between the southern confines of Peru and the river Biobio. The Spanish government was even obliged to allow the Araucanians to keep a minister, or public representative, in the city of St. Jago.

The spirit and character of this brave Indian people made a deep impression upon their invaders. Don Ercilla, a young Spaniard of illustrious family, who accompanied Don Garcia in his Chilian expedition, wrote an epic poem on the events of the war,—the “Araucana,”—which is esteemed one of the best poems in the Spanish language. Ercilla was an eye-witness of many of the scenes he describes, and the following lines show his abhorrence of the mercenary spirit which governed his own countrymen.

The Araucanian are still a free and independent people; and Christians, whose charitable plans embrace the whole heathen world as their mission-ground, may probably find in this nation the best opportunity of planting the Protestant faith which South America now offers.

Rejoicings.—Remorse and contrition.—A pirate’s story.—François restored to his parents.

We left our colonists of Fredonia at the moment that the struggle was over which resulted in the death of Rogere. The scenes which immediately followed are full of interest, but we can only give them a passing notice.

The defeated party sullenly retired to their quarters at the outcast’s cave; and those at the tents were left to rejoice over their deliverance. Their present joy was equal to the anxiety and despair which had brooded over them before. The mothers clasped their children again and again to their bosoms, in the fulness of their hearts; and the little creatures, catching the sympathy of the occasion, returned the caresses with laughter and exultation. The men shook hands in congratulation, and the women mingled tears and smiles and thanksgivings, in the outburst of their rejoicing.

During these displays of feeling, Brusque and Emilie had withdrawn from the bustle, and, walking a part, held discourse together. “Forgive me, Emilie,” said Brusque, “I pray you forgive me for my foolish jealousy respecting the man you were wont to meet by moonlight, at the foot of the rocks. I [Pg 22] now know that it was your brother, and I also know that we all owe our deliverance and present safety to you and him. I can easily guess his story. When the ship was blown up, he had departed, and thus saved his life.”

“Yes,” said Emilie; “but do you know that this weighs upon his spirit like a millstone? He says, that he had voluntarily joined the pirates, and for him to be the instrument of blowing up their ship, and sending them into eternity, while he provided for his own safety, was at once treacherous and dastardly.”

“But we must look at the motive,” said Brusque. “He found that his father, his mother, his sister, were in the hands of those desperate men: it was to save them from insult and death that he took the fearful step. It was by this means alone that he could provide escape for those to whom he was bound by the closest of human ties.”

“I have suggested these thoughts to him,” replied Emilie; “and thus far he might be reconciled to himself; but that he saved his own life is what haunts him; he thinks it mean and cowardly. He is so far affected by this consideration, that he has resolved never to indulge in the pleasures of society, but to dwell apart in the cave, where you know I have been accustomed to meet him. Even now he has departed; and I fear that nothing can persuade him to leave his dreary abode, and attach himself to our community.”

“This is sheer madness,” said Brusque. “Let us go to your father, and get his commands for François to come to the tents. He will not refuse to obey his parent; and when we get him here, we can, perhaps, reason, him out of his determination.”

Brusque and Emilie went to the tent of M. Bonfils, and, opening the folds of the canvass, were about to enter, when, seeing the aged man and his wife an their knees, they paused and listened. They were side by side. The wife was bent over a chest, upon which her face rested, clasped in her hands; the husband,—with his hands uplifted, his white and dishevelled hair lying upon his shoulders, his countenance turned to heaven,—was pouring out a fervent thanksgiving for the deliverance of themselves and their friends from the awful peril that had threatened them. It was a thanksgiving, not for themselves alone, but for their children, their friends and companions. The voice of the old man trembled, yet its tones were clear, peaceful, confiding. He spoke as if in the very ear of his God, who yet was his benefactor and his friend. As he alluded to François, his voice faltered, the tears gushed down his cheeks, and the sobs of the mother were audible.

The suppliant paused for a moment for his voice seemed choked; but soon recovering, he went on. Although François was a man, the aged father seemed to think of him as yet a boy—his wayward, erring boy—his only son. He pleaded for him as a parent only could plead for a child. Emilie and Brusque were melted into tears; and sighs, which they could not suppress, broke from their bosoms. At length the prayer was finished, and the young couple, presenting themselves to M. Bonfils, told him their errand. “Go, my children,” said he, “go and tell François to come to me. Tell him that I have much to say to him.” The mother joined her wishes to this request, and the lovers departed for the cave where François had before made his abode.

As they approached the place, they saw the object of their search, sitting upon a projecting rock that hung over the sea. He did not perceive them at first, and they paused a moment to look at him. He was gazing over the water, [Pg 23] which was lighted by the full moon, and he seemed to catch something of the holy tranquillity which marked the scene. Not a wave, not a ripple, was visible upon the placid face of the deep. There was a slight undulation, and the tide seemed to play with the image of the moon, yet so smooth and mirror-like was its surface as to leave that image unbroken.

After a little time, the two companions approached their moody friend, who instantly rose and began to descend the rocks toward his retreat; but Brusque called to him, and, climbing up the cliff, he soon joined them. They then stated their errand, and begged François to return with them. “Come,” said Brusque, “your father wishes, nay, commands you to return!”

“His wish is more than his command,” said François. “I know not how it is, but it seems to me that my nature is changed: I fear not, I regard not power—nay, I have a feeling within which spurns it; but my heart is like a woman’s if a wish is uttered. I will go with you, though it may be to hear my father’s curse. I have briefly told him my story. I have told him that I have been a pirate, and that I have basely betrayed my companions: but I will go with you, as my father wishes it.”

“Nay, dear François!” said Emilie, throwing her arms around his neck, “do not feel thus. Could you have heard what we have just heard, you would not speak or feel as you do.”

“And what have you heard?” was the reply. Emilie then told him of the scene they had witnessed in the tent, and the fervent prayer which had been uttered in his behalf. “Dear, dear sister!” said François, throwing his powerful arm around her waist, and clasping her light form to his rugged bosom,—“you are indeed an angel of light! Did my father pray for me? Will he forgive me? Will he forgive such a wretch as I am? Will my mother forgive me? Shalt I, can I, be once more the object of their regard, their affection, their confidence?”

“Oh, my brother!” said Emilie, “doubt it not—doubt it not. They will forgive you indeed; and Heaven will forgive you. We shall all be happy in your restoration to us; and however much you may have erred, we shall feel that your present repentance, and the good deeds you have done this night, in saving this little community, your father, your mother, your sister, from insult and butchery, is at once atonement and compensation.”

“Oh, speak not, Emilie, of compensation—speak not of what I have done as atonement. I cannot think of myself but as an object of reproach; I have no account of good deeds to offer as an offset to my crimes. One thing only can I plead as excuse or apology, and that is, that I was misled by evil company, and enlisted in the expedition of that horrid ship while I was in a state of intoxication. This, I know, is a poor plea—to offer one crime as an excuse for another; yet it is all I can give in extenuation of my guilt.”

“How was it, brother? Tell us the story,” said Emilie.

“Well,” said François. “You know that I sailed from Havre, for the West Indies. Our vessel lay for some time at St. Domingo, and I was often ashore. Here I fell in with the captain of the pirate vessel. He was a man of talents, and of various accomplishments. We used often to meet at a tavern, and he took particular pains to insinuate himself into my confidence. We at last became friends, and then he hinted to me his design of fitting out a vessel to cruise for plunder upon the high seas. I rejected the proposal with indignation. My companion sneered at my scruples, [Pg 24] and attempted to reason me into his views. ‘Look at the state of the world,’ said he, ‘and you will remark that all are doing what I propose to do. At Paris they are cutting each other’s throats, just to see which shall have the largest share of the spoils of society—wealth, pleasure, and power. England is sending her ships forth on every ocean: and what are they better than pirates? They have, indeed, the commission of the king—but still it is a commission to burn, slay, and plunder all who do not bow to the mistress of the seas. And why shall not we play our part in the great game of life, as well as these potentates and powers? Why should we not be men—instead of women?

“‘Look at the state of this island—St. Domingo. Already is it heaving and swelling with the tempest of coming revolution. I know secrets worth knowing. Ere a month has rolled away, this place will be deluged in blood. The vast wealth of Port au Prince is now secretly being carried on board the ships, to take flight, with its owners, for places of safety from the coming storm. Let us be on the sea, with a light craft, and we will cut and carve, among them, as we please!’

“Such were the inducements held out to me by the arch-pirate: but it was all in vain, while my mind was clear. I shrunk from the proposal with horror. But now a new scheme was played off. I was led, on one occasion, to drink more deeply than my wont; and being already nearly intoxicated, I was plied with more liquor. My reason was soon lost—but my passions were inflamed. It is the nature of drunkenness to kill all that is good in a man, and leave in full force all that is evil. Under this seduction, I yielded my assent, and was hastened on board the pirate ship, which lay at a little distance from the harbor. Care was taken that my intoxication should be continued; and when I was again sober, our canvass was spread, and our vessel dancing over the waves. There was no retreat; and, finding myself in the gulf, I sought to support my relenting and revolting bosom by drink. At last I partially drowned my remorse; and but for meeting with Brusque on the island, I had been a pirate still.”

By the time this story was done, the party had reached the hut. They entered, and being kindly received by the aged parents, they sat down. After sitting in silence for a few moments, François arose, went to his father, and kneeling before him, asked for his forgiveness. He was yet a young man—but his stature was almost gigantic. His hair was black as jet, and hung in long-neglected ringlets over his shoulders. His countenance was pale as death; but still his thick, black eyebrows, his bushy beard, and his manly features, gave him an aspect at once commanding and striking. When erect and animated, he was an object to arrest the attention and fix the gaze of every beholder. In general, his aspect was stern, but now it was so marked with humiliation and contrition, as to be exceedingly touching. The aged parent laid his hand upon his head, and looking to heaven, said, in a tone of deep pathos, “Father, forgive him!” He could say no more—his heart was too full.

We need not dwell upon the scene. It is sufficient to say, that from that day, François lived with his parents. His character was thoroughly changed: the haughty and passionate bearing, which had characterized him before, had given place to humility and gentleness; and the features that once befitted the pirate, might now have been chosen to set forth the image of a saint. Such is the influence of the soul, in giving character and expression to the features.

(To be continued.)

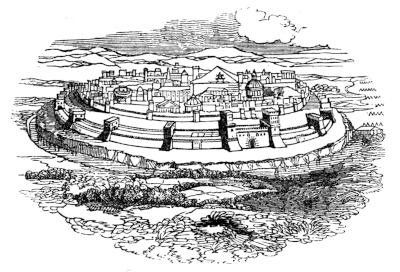

Solon writing laws for Athens.