Project Gutenberg's The Sandman: His Sea Stories, by William J. Hopkins This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Sandman: His Sea Stories Author: William J. Hopkins Illustrator: Diantha W. Horne Release Date: May 10, 2009 [EBook #28748] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SANDMAN: HIS SEA STORIES *** Produced by Tor Martin Kristiansen, Joseph Cooper and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

| he Sandman: |

This special edition is published by arrangement

with the publisher of the regular edition,

The Page Company.

CADMUS BOOKS

E. M. HALE

AND COMPANY

CHICAGO

Copyright, 1908

By The Page Company

All rights reserved

Made in U.S.A.

| Page | |

| The September-Gale Story | 1 |

| The Fire Story | 31 |

| The Porpoise Story | 44 |

| The Seaweed Story | 57 |

| The Flying-Fish Story | 74 |

| The Log-Book Story | 85 |

| The Shark Story | 102 |

| The Christmas Story | 120 |

| The Sounding Story | 139 |

| The Teak-Wood Story | 153 |

| The Stowaway Story | 171 |

| The Albatross Story | 185 |

| The Derelict Story | 194 |

| The Lighthouse Story | 210 |

| The Runaway Story | 222 |

| The Trafalgar Story | 243 |

| The Cargo Story | 253 |

| The Privateer Story | 270 |

| The Race Story | 291 |

| The Pilot Story | 310 |

| The Driftwood Story | 325 |

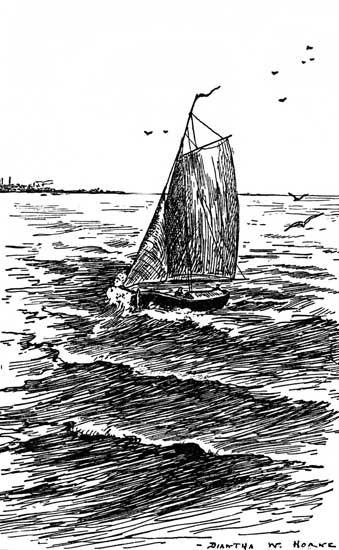

| "They sailed on, in the moonlight." (See page 297) | Frontispiece |

| "Sometimes he had to hold on to the fences" | 11 |

| "They saw all sorts of things going up the river" | 23 |

| "A great tree that was blown down" | 29 |

| "It floated, burning, for a few minutes" | 42 |

| "They swam in a funny sort of way" | 48 |

| "They had more porpoises on deck than you would have thought that they could possibly use" | 55 |

| "The surface of the sea seemed covered with them" | 65 |

| "They amused themselves for a long time" | 72 |

| "A school of fish suddenly leaped out of the water" | 78 |

| "The sailors were having a good time" | 81 |

| The Hour Glass | 90 |

| "Little Jacob liked to watch Captain Solomon" | 93 |

| "'Right there,' he said, 'you can see his back fin'" | 109 |

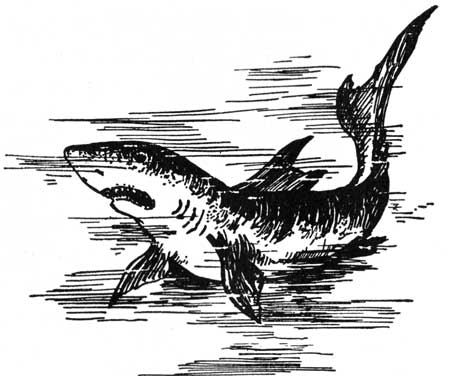

| The Shark | 114 |

| "'Yes, little lad,' he said. 'For you—if you want it'" | 129 |

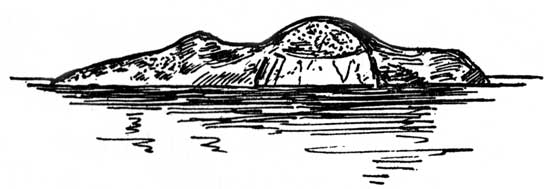

| Christmas Island, 1st View, bearing N by E | 132 |

| Christmas Island, 2nd View, bearing SW | 133 |

| "Little Jacob watched it ... settle into the ocean" | 138 |

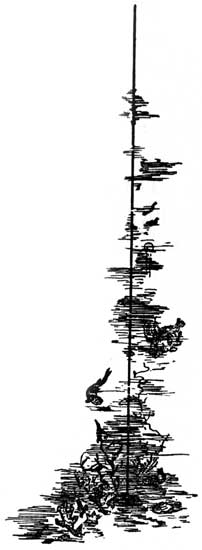

| The Lead | 149 |

| "He walked all around the great yard with the boys on his back" | 167 |

| "He was in the hold of the ship" | 177 |

| The Albatross | 188 |

| "They watched it the day after the next, too" | 192 |

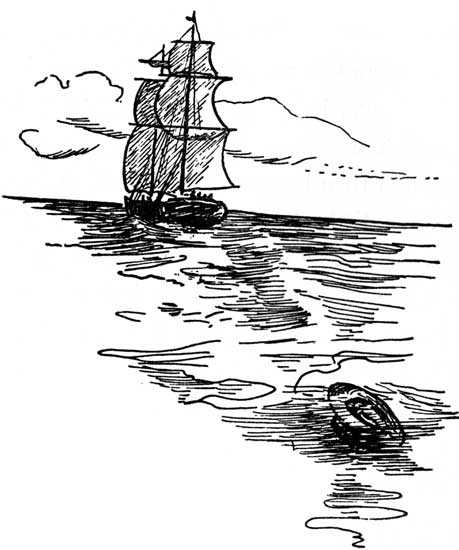

| "Captain Solomon ... was watching the moon" | 199 |

| "The fire blazed up, higher and higher" | 207 |

| "At last he went to sleep" | 213 |

| The Lighthouse | 220 |

| "It was a beautiful farm" | 225 |

| "Took up his bundle and went out the wide gate" | 231 |

| "He started up, thinking of the farm at home" | 235 |

| The Bags of Money | 251 |

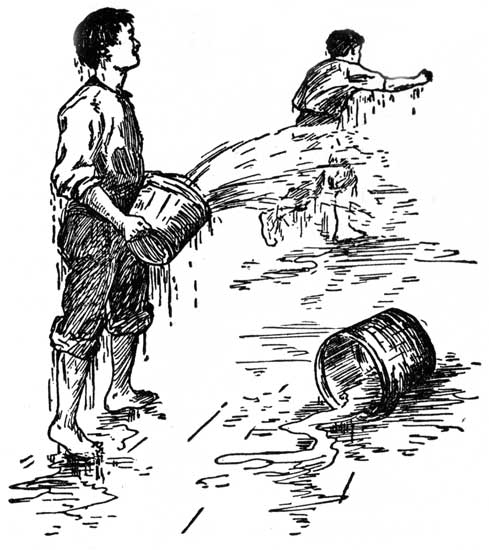

| "Ran to get another bucket" | 267 |

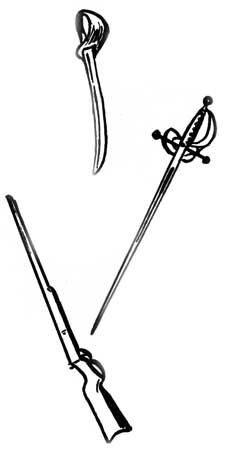

| "With guns and swords and cutlasses" | 272 |

| "That was a signal for the Industry to stop" | 277 |

| "It was a bigger flag than the first one" | 280 |

| "He took it up and looked, very carefully" | 315 |

| "The sloop was on her way" | 319 |

| "Many times had she been tied up at that wharf" | 329 |

| "At last the arm-chair was all done" | 338 |

| The Model of the Industry | 342 |

nce upon a time there was a wide river that ran into the ocean, and beside it was a little city. And in that city was a wharf where great ships came from far countries. And a narrow road led down a very steep hill to that wharf, and anybody that wanted to go to the wharf had to go down the steep hill on the narrow[Pg 2] road, for there wasn't any other way. And because ships had come there for a great many years, and all the sailors and all the captains and all the men who had business with the ships had to go on that narrow road, the flagstones that made the sidewalks were much worn. That was a great many years ago.

The river and the ocean are there yet, as they always have been and always will be; and the city is there, but it is a different kind of a city from what it used to be. And the wharf is slowly falling down, for it is not used now; and the narrow road down the steep hill is all grown up with weeds and grass.

Once, more than a hundred years ago, when ships still came to that wharf, the brig Industry came sailing into that river.[Pg 3] For she was one of the ships that used to come to that wharf, and she used to sail from it to India and China, and she always brought back silks and cloth of goats' hair and camels' hair shawls and sets of china and pretty lacquered tables and trays, and things carved out of ebony and ivory and teakwood, and logs of teakwood and tea and spices. And she had just got back from those far countries and Captain Solomon and all the sailors were very glad to get back. For it was more than a year since she had sailed out of the little river, and they hadn't seen their families for all that long time. And a year is a pretty long time for a man to be sailing on the great ocean and not to see his wife and his dear little boys and girls.

So they hurried and tied the Industry[Pg 4] to the wharf with great ropes and they went away just as soon as they could. And the men that had wives and little boys and girls went to see them, and the others went somewhere. Perhaps they went to the Sailors' Home and perhaps they didn't. But Captain Solomon went to the office of Captain Jonathan and Captain Jacob, who were the owners of the Industry. Their office was just at the head of the wharf, so he didn't have far to go. And Captain Jonathan and Captain Jacob were there waiting for him, and they shook hands with him and sent him packing off home, to see his wife and baby. For Captain Solomon hadn't been married much more than a year and he had sailed away on that long voyage after he had been married four months and he had left[Pg 5] his wife behind. And the baby had been born while he was gone, so that he hadn't seen him yet. That baby was the one that was called little Sol, that is told about in some of the Ship Stories. Captain Solomon wanted to see his wife and his baby, so he hurried off when Captain Jonathan and Captain Jacob told him to.

Then the mate of the Industry got a lot of men and had them take out of the ship all the things that she had brought from those far countries. And they wheeled them, on little trucks, into the building where Captain Jonathan and Captain Jacob had their office, and they piled them up in a great empty room that smelled strangely of camphor and spices and tea and all sorts of other things that make a nice smell.[Pg 6]

At last all the things were taken out of the Industry, so that she floated very high up in the water and the top of her rail, which the sailors look over, was high above the wharf. And Captain Jonathan and Captain Jacob came out of their office to speak to the mate. And the mate said that the Industry was all unloaded; for he was rather proud that he had got all those many things out so quickly.

And Captain Jonathan answered the mate and said how quick he had been. But Captain Jacob didn't say anything, for he was looking around at the sky. The mate saw that Captain Jacob was looking at the sky, and he looked up, too.

"Looks as though we might have a breeze o' wind," he said. For little white[Pg 7] feathery clouds were coming up from the southwest and covering the sky like a thin veil.

Captain Jacob nodded. "More than a breeze," he said; for Captain Jacob had been a truly captain and he knew about the weather.

"I've got out double warps," said the mate; and he meant that he had tied the Industry to the wharf with two ropes instead of one at each place.

Captain Jacob nodded again. "That's well," he said. "That's just as well."

And the mate said "Good night, sir," to Captain Jonathan and he said it to Captain Jacob, too, and they bade him good night, and he went home.

That evening Captain Jacob heard the wind as he was playing chess with Lois.[Pg 8] Lois was Captain Jacob's wife. And Captain Jacob listened to the wind and forgot about the game of chess that he was playing, so that Lois beat him two games. That made Captain Jacob angry, for Lois didn't care much about chess and couldn't play as well as Captain Jacob could. She only played to please Captain Jacob, anyway. And Captain Jacob got so angry that he put the chessmen away and went to bed; but he didn't sleep very well, the wind howled so.

Very early in the morning, long before daylight, Captain Jacob got up. He had been awake for some time, listening to the sound of the rain against his windows and to the howling and shrieking of the wind. And he wondered what was happening down on the river and if the Industry was[Pg 9] all right. He knew well enough what was happening along the shore, and that they would be hearing of wrecks for the next two weeks. They didn't have the telegraph then, so that they wouldn't read in a morning paper what had happened far away during the night, but would have to wait for the stage to bring them the news, or for some boat to bring it. So Captain Jacob got more and more uneasy, until, at last, he couldn't stand it any longer.

And he dressed himself as fast as he could and put on his heavy boots and his great cloak, and he pulled his hat down hard, and he lighted a lantern and started down to the wharf. It was hard work, for the wind was so strong that it almost took him up right off the ground, and blew him along. And sometimes he had to hold[Pg 10] on to the fences to keep himself from blowing away; and he had to watch for a chance, when the wind wasn't so strong for a minute, to cross the streets. Once he heard a great crash, and he knew that that was the sound of a chimney that the wind had blown over. But he couldn't stop to attend to that.[Pg 11]

"SOMETIMES HE HAD TO HOLD ON TO THE FENCES"

"SOMETIMES HE HAD TO HOLD ON TO THE FENCES"

[Pg 12]When he got to the wharf, he was surprised to see how high the hull of the Industry was. It wasn't daylight yet, but he could just make out the bulk of it against the sky. And he was surprised because he knew that it would not be time for the tide to be high for three hours yet, and the Industry was floating as high as she would at a very high tide. So Captain Jacob made his way very carefully out on the wharf, holding on to ropes and[Pg 13] to other things when there were other things to hold on to, and crouching down low, for he didn't want to be blown off into the water.

At last he got to the edge, and he held his lantern over and looked down at the water. And the top of the water was only about three feet down, for the wind was blowing straight up the river from the ocean, and it was so strong that it had blown the water from the ocean into the river. And it was still blowing it in, and was getting stronger every minute.

Captain Jacob looked at the water a minute. "Hello!" he said. But nobody could have heard him, there was such a noise of the wind and of the waves washing against the wharf. He didn't say it to anybody in particular, so he wasn't[Pg 14] disappointed that nobody heard him. And he listened again, and he thought he heard a noise as though somebody was on the Industry. So he climbed up the side, with his lantern, and there he saw the mate, for it was just beginning to be a little bit light in the east. The mate was trying to do something with an anchor; but the anchors were great, enormous, heavy things, and one man couldn't do anything with them at all.

Captain Jacob went close beside the mate. "What you trying to do?" he yelled, as loud as he could.

"What, sir?" asked the mate, yelling as loud as he could.

"What—you—trying—to—do?" asked Captain Jacob again. The wind was playing a tune on every rope on the ship[Pg 15] and singing a song besides, so that the noise, up there on the deck, was fearful.

"Trying to get an anchor out in the river," yelled the mate, putting his hands to his mouth like a trumpet. "Wharf's going to be flooded as the tide rises. Afraid she'll capsize!"

"You can't do it alone," yelled Captain Jacob.

"No," yelled the mate. "Can't! Get some men!"

"Good!" yelled Captain Jacob. And the mate climbed down the side.

But the mate didn't have to go far, for some men were already coming as well as they could, holding on by the fences on the way, and the mate met those men. And they came on the Industry, and lowered the biggest boat that she had into[Pg 16] the water, and they all managed to get in, somehow or other, and to hold the boat while Captain Jacob and the mate lowered the anchor into the boat, winding the chain around the capstan. The anchor was so heavy that it nearly sunk the boat, but it didn't quite sink it. The end of the boat that the anchor was on was so near the water that water kept splashing in.

Then the men all rowed very hard and the boat went ahead slowly, while Captain Jacob and the mate let out more of the anchor chain. But they couldn't go very far, for the wind was so strong and the waves were so high and the heavy anchor chain held them back near the ship. When they had got as far as they could, they managed to pry the anchor over[Pg 17]board. It went into the water with a tremendous splash, wetting all the men; but they didn't mind, for they were all wet through already with the rain and the splashing of the waves. And the boat turned around and went back to the shore. But the men didn't try to row it back to the Industry. The wind blew them up the river, so that they got to the shore three or four wharves up, beyond the railway where they pulled ships up out of the water to mend them. They then walked back as quickly as they could.

Captain Jacob and the mate had been working hard, taking in some of the anchor chain. They put two of the bars in the capstan head and pushed as hard as they could, and they had managed to get a strain on the anchor by the time the[Pg 18] men got back. It was daylight, by this time, and the tide had risen so much that the men had to go splashing through water that was up to their ankles all over the top of the wharf. But they didn't care, and they got up on the ship, and some of them put more bars in the capstan head and pushed, and some of them let out more of the great ropes that held the ship to the wharf. They wanted to get her away from the wharf and out in the river, for they were afraid that the wind might blow her right over upon the wharf and tip her over. Then it would be very hard to get her into the water again.

When the anchor chain was pulled in enough, they fastened it and went to the stern and down one of the great ropes that[Pg 19] held the Industry to the wharf. They went down, half sliding and half letting themselves down by their hands, and Captain Jacob and the mate and all the men that were on the ship went down that way. They all had been sailors, and a sailor has to learn to do such things and not to be afraid. And they all splashed into the water that was on the top of the wharf. Then they let out the ropes from that end, but they didn't let them go. And the Industry lay out in the river, at anchor, about five fathoms from the end of the wharf. A fathom is six feet, and sailors generally measure distances in fathoms instead of in feet.

As soon as Captain Jacob had got to the wharf he yelled to the men and waved his hand to them, for he was afraid that[Pg 20] they could not hear him if he tried to tell them anything. And he started very carefully across the wharf, holding on to anything he could get hold of, and all the men followed him. It was very hard work and very dangerous, too, going about on top of the wharf, for the water was nearly up to the men's knees, and it was all wavy. And Captain Jacob led the way to the office and opened the door and they all went in.

As soon as they were inside, they began taking all the things that were piled up in that great room that had the nice smell, and they carried them up stairs. They didn't wait to be told what to do, for they knew well enough that Captain Jacob was afraid that the tide might rise so high that the floor of that room and of the office[Pg 21] would be covered with water and all the pretty things would be wet and spoiled. Of course, water wouldn't spoil the china and such things, but it would spoil the shawls and the silks and the tea and the spices. So they worked hard until they had all the things up stairs.

And, by that time, the water was beginning to come in at the door and to creep along over the floor; and Captain Jacob and the mate and all the men went outside, and stood where they were sheltered from the wind, and they watched the river, that stretched out very wide indeed, and they watched the things that were being driven up on its surface by the wind, and they watched the Industry.

They were all standing in the water, but they didn't know it. And they saw all[Pg 22] sorts of things going up the river, with the wind and the waves: many small boats that had been dragged from their moorings or off the beaches; and some larger boats that belonged to fishermen; and some of the fishermen's huts that had stood in a row on a beach; and a part of a house that had been built too near the water; and logs and boards from the wharves and all kinds of drifting stuff. It was almost high tide now, and the wind was stronger than ever. None of the men had had any breakfast, but they didn't think of that.[Pg 23]

"THEY SAW ALL SORTS OF THINGS GOING UP THE RIVER"

"THEY SAW ALL SORTS OF THINGS GOING UP THE RIVER"

[Pg 24]"About the height of it, now," said the mate to Captain Jacob. They could hear each other speak where they were standing, in a place that was sheltered by the building. "Not so bad here, in the lee of[Pg 25] the office. And the wind'll go down as the tide turns, I'm thinking."

Captain Jacob nodded. He was watching the Industry pitching in the great seas that were coming up the river.

"She ought to have more chain out," he said anxiously. "I wish we could have given her more chain. It's a terrible strain."

"If a man was to go out to her," began the mate, slowly, "he might be able to give her more. He could shin up those warps——"

"Don't think of it!" said Captain Jacob. "Don't think of it!"

As he spoke, the ship's bow lifted to a great sea, there was a dull sound that was scarcely heard, and she began to drift, slowly, at first, until she was broadside[Pg 26] to the wind. The anchor chain had broken; but the great ropes that were fastened to the wharf still held her by the stern. Then she drifted faster, in toward the wharves. There was a sound like the report of a small cannon; then another and another. The great ropes that had held her to the wharf had snapped like thread.

"Well," said Captain Jacob, "now I wonder where she'll bring up. We can't do anything."

So they watched her drifting in to the wharf where the railway was, where they pulled ships up out of the water to mend them. And Captain Jonathan was coming down to the office just as the Industry broke adrift, and he saw that she would come ashore at the railway. So[Pg 27] he stopped there and waited for her to come. They had there a sort of cradle, that runs down into the water on rails; and a ship fits into the cradle and is drawn up out of the water to be mended. And Captain Jonathan thought of that, and he thought that it wouldn't do any harm to lower the cradle and see if the Industry wouldn't happen to fit into it. It might not do any good, but it couldn't do any harm; and the Industry was all unloaded, and floated very high in the water.

So Captain Jonathan and two other men, who belonged at that railway, lowered the cradle as much as they thought would be right, and the Industry drifted in and she did happen to catch on the cradle. She didn't fit into it exactly, for she[Pg 28] was heeled over by the wind, and she caught on the cradle more on one side than the other; but Captain Jonathan thought that she would go into the water all right when the tide went down a little and the cradle was lowered more. And he was glad that he had happened to think of it.

Then, pretty soon, the tide began to go out again, and the wind stopped blowing so hard. And, in an hour, there was not more than a strong gale blowing, and men began to go out in row boats that hadn't broken adrift, and to pick things up as they came down with the tide. The sea was very rough, but they were afraid that the things would drift out to sea if they waited.

And, in a couple of hours more, Captain[Pg 29] Jonathan and Captain Jacob and the mate and all the men had the Industry afloat again and were warping her back to her wharf. There was no great harm done; only some marks of scraping and bumping and the anchor down at the bottom of the river.

Then Captain Jonathan and Captain Jacob went home to dinner, and pretty soon all the men went, too. And they saw a great many chimneys blown over into yards and a great many fences blown down; and they came to a great tree that was blown down across the street, and then they saw another and a third. And they had to go[Pg 30] through somebody's yard to get around these trees. And, when they got home, they heard about an old woman who had tried to go somewhere, who had been picked up by the wind and carried a long way and set down again on her own doorstep. And she had taken the hint and gone into the house.

That great wind, they called the Great September Gale, for it happened in the early part of September. That is the time of the year that such great winds are most apt to come. And all the people had it to talk about for a long time, for there wasn't another such gale for more than twenty years.

And that's all.[Pg 31]

nce upon a time there was a wide river that ran into the ocean, and beside it was a little city. And in that city was a wharf where great ships came from far countries. And a narrow road led down a very steep hill to that wharf, and anybody that wanted to go to the wharf had to go down the steep hill on the narrow road, for there wasn't any other way. And because ships had come there for a great many years and all the sailors and all the captains and all the men who had business with the ships had to go on that[Pg 32] narrow road, the flagstones that made the sidewalk were much worn. That was a great many years ago.

The river and the ocean are there yet, as they always have been and always will be; and the city is there, but it is a different kind of a city from what it used to be. And the wharf is slowly falling down, for it is not used now; and the narrow road down the steep hill is all grown up with weeds and grass.

One day, in the long ago, the brig Industry sailed away from that wharf, on a voyage to India. And she sailed down the wide river and out into the great ocean and on and on until the land was only a dim blue streak on the horizon; and farther on, and the land sank out of sight, and there was nothing to be seen, wher[Pg 33]ever Captain Solomon looked, but that great, big water, that was so blue and that danced and sparkled in the sunshine. For it was a beautiful afternoon and there was just a gentle wind blowing, so that the Industry had every bit of sail set that could be set: mainsail and foresail and spanker, main-topsail, and fore-topsail, main-topgallantsail and fore-topgallantsail and main-royal and fore-royal and main-skysail and fore-skysail and staysails and all her jibs and a studdingsail on every yard, out on its boom. She was sailing very fast, and she was a pretty sight, with that cloud of canvas. She looked like a great white bird. I wish that you and I could have seen her.

And the crew didn't have much to do, when they had got all those sails set.[Pg 34] They had already been divided into watches, so that every man knew what his duty would be, and when he would have to be on deck, ready to work, and when he could sleep. And they stood at the rail, mostly, and they leaned on it and looked out over the water in the direction of that little city that they were leaving behind them and that they wouldn't see again for nearly a year. They couldn't see the little city because it was down behind the roundness of the world; but they saw the sun, which was almost setting. And the sun sank lower and lower until it sank into the sea. And there were all sorts of pretty colors, in the west, which changed and grew dim, and disappeared. And the stars came out, one by one, and it was night.

Captain Solomon didn't have any of[Pg 35] those many sails taken in, because he knew that it would be pleasant weather all night, and that the wind would be less rather than more. And it was such a beautiful night that he didn't go to bed early, but stayed on deck until it was very late; and he watched the stars and the water and he listened to the wash of the waves as the ship went through them and he saw the foam that she made; and he felt the gentle wind blowing on his cheek, and it all seemed very good to him. Captain Solomon loved the sea. Then, when it was very late, and they were just going to change the watch, he went into the cabin to go to bed.

Before he had got his clothes off, he heard a commotion on deck, and the mate came running down.[Pg 36]

"The ship's on fire, sir," he said. "There's smoke coming out of the forward hatch."

Captain Solomon said something and threw on his clothes that he had taken off and ran out on deck. It was less than half a minute from the time the mate had told him. And he saw a little, thin column of smoke rising out of the forward hatchway, just as the mate had said. They had the hatch off by this time, and the sailors were all on deck. The hatchway is a square hole in the deck that leads down into the hold, where the things are put that the ship carries. It has a cover made of planks, and the cover fits on tightly and can be fastened down. It usually is fastened when the ship is going.

Captain Solomon spoke to the mate.[Pg 37] "Put her about on the other tack," he said, "and head for Boston, while we fight it. If we get it under, as I think we will, we'll lose only a couple of hours. If we don't, we can get help there. We ought to make Boston by daylight."

"Aye, aye, sir," said the mate. And he gave the orders in a sharp voice, and most of the crew jumped for the sails and the ropes and pulled and hauled, and they soon had the ship heading for Boston. But the second mate and a few of the sailors got lanterns and lighted them.

And, when they had lighted their lanterns, the second mate jumped down the hatchway into the smoke, and four sailors jumped down after him. And they began tumbling about the bales of things; but they couldn't tumble them about very[Pg 38] much, for there wasn't room, the cargo had been stowed so tightly. And the second mate asked Captain Solomon to rig a tackle to hoist some of the things out on deck.

"Doing it, now," answered Captain Solomon. "It'll be ready in half a minute."

And they got the tackle rigged right over the hatchway, and they let down one end of the rope to the second mate. This end of the rope that was let down had two great, iron hooks that could be hooked into a bale, one on each side. And the second mate and the sailors that were down there with him hooked them into a bale and yelled. Then a great many of the sailors, who already had hold of the other end of the rope, ran away with it, so that the bale came up as if it had been[Pg 39] blown up through the hatchway. Then other sailors caught it, and threw it over to one side and unhooked the hooks, and they let them down into the hold again.

They got up a great many bales in this way, and they did it faster than the Industry had ever been unloaded before. And the sailors that ran away with the rope sang as they ran.

"What shall we do with a drunken sailor?"

was the chanty that they sang. And, at last, the second mate and the four sailors came out of the hold, and they were choking with the smoke and rubbing their eyes.

"Getting down to it, sir," said the second mate, "but we couldn't stand any more."[Pg 40]

So the first mate didn't wait, but he took the second mate's lantern and jumped down.

"Four men follow me!" he cried; and all the other sailors, who hadn't been down yet, jumped for the lanterns of the four sailors who had been down, and Captain Solomon laughed.

"That's the way to do it!" he cried. "That's the sort of spirit I like to see. We'll have it out in a jiffy. Four of you men at a time. You'll all have a turn. Man the pumps, some of you, and be ready to turn a stream down there if it's wanted."

So the four who had been nearest to the lanterns went down, and some of the others tailed on to the rope, and still others got the pumps ready and rigged a hose[Pg 41] and put the end of it down the hatchway. But they didn't pump, because Captain Solomon knew that water would do harm to the cargo that wasn't harmed yet, and he didn't want to pump water into the hold unless he had to.

Then they all hurried some more and got out more bales, until the mate and his four men had to come up; but there were more men waiting to go down, and, this time, Captain Solomon led them.

He hadn't been there long before he called out. "Here she is!" he said. And the sailors hoisted out a bale that was smoking. As soon as it was on deck, out in the air, it burst into flames.

Captain Solomon had come up. "Heave it overboard!" he cried. And four sailors took hold of it and heaved it over the side[Pg 42] into the water. The Industry was sailing pretty fast and quickly left it astern, where it floated, burning, for a few minutes; then, as the water soaked into the bale, it got heavier, and sank, and the sailors saw the light go out, suddenly.

Captain Solomon drew a long breath. "Put her on her course again, Mr. Steele," he said to the mate. "We won't lose any more time. You can have this mess cleared up in the morning."[Pg 43]

And the sailors jumped for the ropes, although they were pretty tired, and they swung the yards around, two at a time, with a chanty for each. The Industry was sailing away for India again. And, the next day they cleared the smoke out of the hold, and they stowed the cargo that had been taken out in the night, and they put on the hatch and fastened it.

And that's all.[Pg 44]

nce upon a time there was a wide river that ran into the ocean, and beside it was a little city. And in that city was a wharf where great ships came from far countries. And a narrow road led down a very steep hill to that wharf, and anybody that wanted to go to the wharf had to go down the steep hill on the narrow road, for there wasn't any other way. And because ships had come there for a great many years and all the sailors and all the captains and all the men who had business with the ships had to go on that[Pg 45] narrow road, the flagstones that made the sidewalk were much worn. That was a great many years ago.

The river and the ocean are there yet, as they always have been and always will be; and the city is there, but it is a different kind of a city from what it used to be. And the wharf is slowly falling down, for it is not used now; and the narrow road down the steep hill is all grown up with weeds and grass.

Once, in the long ago, the brig Industry had sailed away from the wharf and out into the great ocean on a voyage to India. And she had been gone from the wide river three or four days, and she was well out into the ocean and no land was in sight, but only water and once in a while another ship. But they didn't see ships as[Pg 46] often as they had at first, and it was good weather and the wind was fair, so that there wasn't anything much for the sailors to do. The mates kept them as busy as they could, washing down the deck and coiling ropes, and doing a lot of other things that didn't need to be done, for the Industry had just been fixed up and painted and made as clean as she could be made. And that was pretty clean. So the sailors didn't care very much about doing a lot of things that didn't need to be done, but they did them, as slowly as they could, because, if they said that they wouldn't do things that the mates or the captain told them to do, that would be mutiny. And mutiny, at sea, is a very serious thing for everybody. It satisfied Captain Solomon and the mate well[Pg 47] enough to have the men do things slowly, so long as they did them. For they knew that the men would do things quickly if there was any need for quickness.

Then, one morning, just as it began to be light, the man who was the lookout thought that he saw something in the water about the ship that didn't look quite like waves. And it got a little lighter so that he could make sure, and he called some others of his watch and told them to look and see the school of porpoises. And they all looked, and those men told others who looked over the side, too, and pretty soon all the men of that watch were leaning on the rail and looking at the porpoises. That made the mate who was on watch look over, too, so that every man on deck was looking over[Pg 48] the side into the water. Then the sun came up out of the water.

What they saw was a great many big fishes, all black and shining, and each one had spots of white on its side and a funny-shaped head. Most of them seemed to be about the size of a man, and they swam in a funny sort of way, in and out of the water, so[Pg 49] that their backs showed most of the time, and they glistened and shone and their spots of white made them rather a pretty sight. And now and then they spouted little jets of water and spray out of their heads into the air, just as if they were little whales. Porpoises are more like little whales than they are like fishes, for they have to breathe air, just as whales do, and they spout just as whales do, and they are like whales in other ways. They aren't really fishes, at all.

The Industry was sailing very fast, for the wind was fair and strong, and she had all the sails set that she could set; but the porpoises didn't seem to think she was going very fast, for they had no trouble at all to keep up with her and they could play by the way, too. And[Pg 50] so they did, hundreds of them. Some of them kept just ahead of her stem, where it cut through the water, and they leaped and gambolled, but the ship never caught up with them. And they were doing the same thing all about.

Seeing the porpoises that kept just ahead of the Industry made the sailors think of something and they all thought of the same thing at once. Perhaps it was because it was about breakfast time. Four of the men went aft to speak to the mate, who was standing where the deck is higher. And the mate didn't wait for them to speak, for he knew just what they were going to ask him. The men had their hats in their hands by the time they got near.

The mate smiled. "Yes, you may," he[Pg 51] said. "I'll get 'em." And he went into the cabin.

When he had gone the men grinned at each other and looked pleased and each man was thinking that the mate was not so bad, after all, even if he did make them do work that didn't need to be done, just to kept them busy. But they didn't say anything.

Then the mate came out, and he had two harpoons in his hand.

"There!" he said. "Two's enough. You'd only get in each other's way if there were more. Bend a line on to each, and make it fast, somewhere."

Then Captain Solomon came on deck, and he offered a prize of half a pound of tobacco to the best harpooner. And the men cheered when they heard him,[Pg 52] and they took the harpoons and ran forward.

They hurried and fastened a rather small rope on to each harpoon, in the way a rope ought to be fastened to a harpoon, and two of the sailors took the two harpoons and went down under the bowsprit, in among the chains that go from the end of the bowsprit to the stem of the ship. They went there so as to be near the water. They might get wet there, but they didn't care about that. And the other end of the rope, that was fastened to each harpoon, was made fast up on deck, so that the harpoon shouldn't be lost if it wasn't stuck into a porpoise, and so that the porpoise shouldn't get away if it was stuck into him.

One of the sailors was so excited that he didn't hit anything with his harpoon,[Pg 53] and the sailors up on deck hauled it in. The other sailor managed to hit a porpoise, but he was excited, too, and the harpoon didn't go in the right place. When the sailors up on deck tried to haul the porpoise in, it broke away, and went swimming off.

Then those sailors came back on deck and two others took their places. One of those others had been harpooner on a whaleship before he went on the Industry. He didn't get excited at harpooning a porpoise, but drove his harpoon in at just exactly the right place, and the sailors up on deck hauled that porpoise in. Afterwards, that sailor got the half pound of tobacco that Captain Solomon had offered as a prize, because he harpooned his porpoise just exactly the right way.[Pg 54]

The sailor that went with him struck a porpoise, too, but it wasn't quite in the right place, and the men had hard work to get him.

And then other sailors came and tried, and they took turns until they had more porpoises on deck than you would have thought that they could possibly use.

And all the men had porpoise steak for breakfast that morning and porpoise steak for dinner, and porpoise steak for supper. Sailors call porpoises "puffing pigs," and porpoise steak tastes something like pork steak, and sailors like it. But they had it for every meal until there was only one porpoise left, and that one they had to throw overboard.

And that's all.[Pg 55]

"THEY HAD MORE PORPOISES ON DECK THAN YOU WOULD HAVE

THOUGHT THAT THEY COULD POSSIBLY USE"

"THEY HAD MORE PORPOISES ON DECK THAN YOU WOULD HAVE

THOUGHT THAT THEY COULD POSSIBLY USE"

nce upon a time there was a wide river that ran into the ocean, and beside it was a little city. And in that city was a wharf where great ships came from far countries. And a narrow road led down a very steep hill to that wharf, and anybody that wanted to go to the wharf had to go down the steep hill on the narrow road, for there wasn't any other way. And because ships had come there for a great many years and all the sailors and all the captains and all the men who had[Pg 58] business with the ships had to go on that narrow road, the flagstones that made the sidewalk were much worn. That was a great many years ago.

The river and the ocean are there yet, as they always have been and always will be; and the city is there, but it is a different kind of a city from what it used to be. And the wharf is slowly falling down, for it is not used now; and the narrow road down the steep hill is all grown up with weeds and grass.

The wharf was Captain Jonathan's and Captain Jacob's and they owned the ships that sailed from it; and, after their ships had been sailing from that wharf in the little city for a good many years, they made up their minds that they ought to move their office to Boston. And so they[Pg 59] did. And, after that, their ships sailed from a wharf in Boston and Captain Jonathan and Captain Jacob had their office on India street. Then the change began in that little city and that wharf.

Once, in the long ago, the brig Industry had sailed from Boston for a far country, and little Jacob had gone on that voyage. Little Jacob was Captain Jacob's son and Lois's, and the grandson of Captain Jonathan, and when he went on that voyage he was almost thirteen years old. And little Sol went, too. He was Captain Solomon's son, and he was only a few months younger than little Jacob. Captain Solomon had taken him in the hope that the voyage would discourage him from going to sea. But, as it turned out, it didn't discourage him at all, but he liked going[Pg 60] to sea, so that afterwards he ran away and went to sea, and became the captain of that very ship, as you shall hear.

The Industry had been out a little more than a week, and she had run into a storm. The storm didn't do any harm except to blow her out of her course, and then she ran out of it. And the next morning little Jacob came out on deck and he looked for little Sol. The first place that he looked in was out on the bowsprit; for little Sol liked to be out there, where he could see all about him and could see the ship making the wave at her bow and feel as if he wasn't on the ship, at all, but free as air. It was a perfectly safe place to be in, for there were nettings on each side to keep him from falling, and he didn't go out beyond the nettings onto[Pg 61] the part that was just a round spar sticking out.

When little Jacob got to the bow of the ship, he looked out on the bowsprit, and there was little Sol; but he wasn't lying on his back as he was most apt to be, nor he wasn't lying down with one hand propping up his head, which was the way he liked to lie to watch the wave that the ship made. He was lying stretched out on his stomach, with both hands propping up his chin, and he was looking straight out ahead, so that he didn't see little Jacob. And the Industry was pitching a good deal, for the storm had made great waves, like mountains, and the waves that were left were still great. The ship made a sort of growling noise as she went down into a wave, and a sort of hissing noise as[Pg 62] she came up out of it, and little Jacob was—well, not afraid, exactly, but he didn't just like to go out there where little Sol was, with the ship making all those queer noises. You see, it was little Jacob's first storm at sea. It was little Sol's first storm, too; but then, boys are different.

So little Jacob called. "Sol!" he said.

Little Sol turned his head quickly. "Hello, Jake," said he. "Come on out. There's lots to see out here to-day."

"Are—are there things to see that I couldn't see from here?" asked little Jacob.

"Of course there are," answered little Sol, scornfully. "You can't see anything from there—anything much."

"The ship pitches a good deal," remarked little Jacob. "Don't you think so?"[Pg 63]

"Oh, some," said little Sol, "but it's safe enough after you get here. You could crawl out. I walked out. See here, I'll walk in, to where you are, on my hands."

And little Sol scrambled up and walked in on his hands, with his feet in the air. He let his feet down carelessly. "There!" he said. "You see."

"Well," said little Jacob. "I can't walk on my hands, because I don't know how. You show me, Sol, will you?—when it's calm. And I'll walk out on my feet."

Little Jacob was rather white, but he didn't hesitate, and he walked out on the bowsprit to the place where he generally sat. It was rather hard work keeping his balance, but he did it. And little Sol came after, and said he would show him how to walk on his hands, some day[Pg 64] when it was calm enough. For little Sol didn't think little Jacob was afraid, and the two boys liked each other very much.

"There!" said little Sol, when they were settled, "you look out ahead, and see if you see anything."

So little Jacob looked and looked for a long time, but he didn't know what he was looking for, and that makes a great difference about seeing a thing.

"I don't see anything," said he. "What is it, Sol—a ship!"

"No, oh no," answered little Sol. "It's on the water—on the surface. We've almost got to one of 'em."[Pg 65]

So little Jacob looked again, and he saw what looked, at first, like a calm streak on the water. There seemed to be little sticks sticking up out of the calm streak. Then he saw that it looked like a narrow island, except that it went up and down with the waves. Sometimes he saw one part of it, and then he saw another part. And the island was all covered with water, and the water near it was calm, and it was a yellowish brown, like seaweed. In a minute or two the Industry was ploughing through it, and he could see that it was a great mass of floating seaweed that gave way, before the ship, like water, and[Pg 66] the little sticks that he had seen, sticking up, were the stems. A little way ahead there was another of the floating islands; and another and another, until the surface of the sea seemed covered with them. They were really fifteen or twenty fathoms apart; but, from a distance, it didn't look as if they were.

"Why, Sol," said little Jacob, in surprise, "it doesn't stop the ship at all. I should think it would. What is it?"

"Well," answered little Sol. "I asked one of the men, and he laughed and said it was nothing but seaweed—that the ship would make nothing of it. I was afraid we were running aground. And the man said that the rows—it gets in windrows, like hay that's being raked up—he said that the windrows were broken[Pg 67] up a good deal by the storm; that he's often seen 'em stretching as far as the eye could see, and a good deal thicker than these are."

Little Jacob laughed. "What are you laughing at?" asked little Sol, looking up.

"'As far as the eye could see,'" said little Jacob.

"Well," said little Sol, "that's just what he said, anyway."

"I'm going to ask your father about it," said little Jacob. "He'll know all about it. He always knows." And he got up, carefully, and made his way inboard; then he ran aft, to look for Captain Solomon.

He found Captain Solomon on the quarter deck, leaning against the part of the cabin that stuck up through the deck.[Pg 68] He was half sitting on it and looking out at the rows of seaweed that they passed. So little Jacob asked him.

"Yes, Jacob," answered Captain Solomon, "it's just seaweed, nothing but seaweed. We're just on the edge of the Sargasso Sea, and that means nothing but Seaweed Sea. The weed gets in long rows, just as you see it now, only the rows are apt to be longer and not so broken up. It's the wind that does it, and the ocean currents. It's my belief that the wind is the cause of the currents, too. I've seen acres of this weed packed so tight together that it looked as if we were sailing on my south meadow just at haying time. I don't see that south meadow at haying time very often, now, but I shall see it, please God, pretty soon."[Pg 69]

"Well," said little Jacob, "I should think that it would get all tangled up so that it would stop the ship."

"My south meadow?" asked Captain Solomon. He was thinking of haying, and he had forgotten the Seaweed Sea.

Little Jacob laughed. "No, sir," he answered. "The seaweed. Why doesn't it get all tangled like ropes, so that it stops the ship?"

"The plants aren't long enough," said Captain Solomon. "Come, we'll get some of it for you."

"Oh!" cried little Jacob. "Will you? Thank you, sir."

And Captain Solomon told two of the sailors to come and to bring a big bucket. The bucket had a long rope fastened across, and the end was long enough to[Pg 70] reach from the water up to the deck of the Industry. They use buckets like that to dip up the salt water; and, when the ship is going the sailors have to be very careful and very quick or they will lose the bucket, it pulls so hard.

So one sailor dipped the bucket just as they were passing over one of the rows of seaweed; and the other sailor took hold of the rope, too, as soon as he had dipped the bucket, and they pulled it up and set it on deck. Captain Solomon stooped and took up a plant. There were two plants in the bucket. Little Sol had come when he saw the sailors with the bucket.

And Captain Solomon showed the boys that a plant was about the size of a cabbage, and that it had a great many little[Pg 71] balloons that grew on it about as big as a pea, and these balloons were filled with air to make the plant float. Some of them were almost as big as a nut, and little Sol and little Jacob had fun trying to make them pop.

Then little Sol found a tiny fish in the bucket that was just the color of the weed; and little Jacob saw another, and then he saw a crab drop from the weed that Captain Solomon was holding, and the crab was just the color of the weed, too. And they amused themselves for a long time with hunting for the queer fishes and crabs and shrimps, and something that was like a mussel, but it wasn't just like one, either. And they found a place in the weed where were some little balls. And they opened the balls, and[Pg 72] little Sol said he'd bet that they were where some animal laid its eggs. But little Jacob didn't say anything, for he didn't pretend to know anything about it. But Captain Solomon got tired of holding that weed, so he dropped it back into the[Pg 73] bucket and went away. And, at last, when little Jacob and little Sol got tired of hunting for things in the weed, the sailors threw it over into the ocean again.

And that's all.[Pg 74]

nce upon a time there was a wide river that ran into the ocean, and beside it was a little city. And in that city was a wharf where great ships came from far countries. And a narrow road led down a very steep hill to that wharf, and anybody that wanted to go to the wharf had to go down the steep hill on the narrow road, for there wasn't any other way. And because ships had come there for a great many years and all the sailors and all the captains and all the men who had business[Pg 75] with the ships had to go on that narrow road, the flagstones that made the sidewalk were much worn. That was a great many years ago.

The river and the ocean are there yet, as they always have been and always will be; and the city is there, but it is a different kind of a city from what it used to be. And the wharf is slowly falling down, for it is not used now; and the narrow road down the steep hill is all grown up with weeds and grass.

The wharf was Captain Jonathan's and Captain Jacob's and they owned the ships that sailed from it; and, after their ships had been sailing from that wharf in the little city for a good many years, they changed their office to Boston. After that their ships sailed from a wharf in Boston.[Pg 76]

Once, the brig Industry had sailed from Boston for a far country and she had got down into the warm parts of the ocean. Little Jacob and little Sol had gone on that voyage. Little Sol always got out on deck, in the morning, a little while before little Jacob got out. And, one morning, he had gone on deck and little Jacob was hurrying to finish his breakfast, when little Sol came running back and stuck his head in at the cabin door.

"Oh, Jake," he called, "come out here, quick! There are fishes with wings on 'em, and they are flying all 'round."

Then little Jacob was very much excited, and he wanted to leave the rest of his breakfast and go out. All of a sudden he found that he wasn't hungry. But[Pg 77] Captain Solomon was there, and he smiled at little Jacob's eagerness.

"Better finish your breakfast, Jacob," he said. "The flying fish won't go away—not before you get through."

"Thank you, sir," said little Jacob. "I'm all through. I don't feel hungry for any more."

"All right," said Captain Solomon. "But if you and Sol get hungry you can go to the cook. I have an idea that he will have something for you."

Little Jacob was already half way up the cabin steps. "Thank you, sir," he said; but there was some doubt whether he had heard. Captain Solomon smiled again and got up and followed him.

Little Sol was in his favorite place on the bowsprit, and little Jacob was going[Pg 78] there as fast as he could. He settled himself in his place and began to look around.

"Where, Sol?" he asked. "Where are the—oh!"

For, just ahead of the ship, a school of fish suddenly leaped out of the water, and went flying about fifteen or twenty feet above the water for a hundred feet or more. And they kept coming. Little Jacob could hear the humming of their long fins, but he couldn't see their fins, they went so fast. Little Sol had thought they were wings; and it was as nearly[Pg 79] right to call them wings as to call them fins.

"Oo—o, Sol!" cried little Jacob. "Aren't they pretty? And aren't they small? And don't they fly fast?"

"M—m," said little Sol.

"Look at these over there!" cried little Jacob, again. "See! They are flying faster than the ship is going. They are beating us!"

Little Jacob was pointing to some fish that were flying in the same direction that the Industry was sailing. They went ahead of her and dropped into the water.

"H'mph!" said little Sol. "There isn't much wind, anyway. If there was, I'll bet they wouldn't beat us." There really was a good deal of wind.[Pg 80]

"But aren't they pretty colors, Sol?" said little Jacob. "They're all colors of blue and silvery. I can't see them very plainly, they go so fast. I wish I could see them plainer."

Captain Solomon was standing near enough to hear what little Jacob said.

"If you'll come inboard, Jacob," said Captain Solomon, "you can see them. We're catching them."[Pg 81]

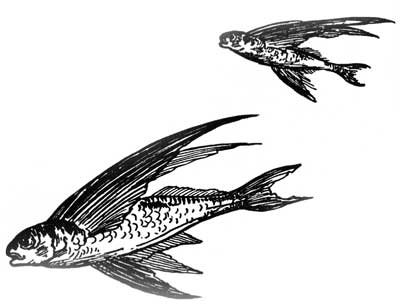

"THE SAILORS WERE HAVING A GOOD TIME"

"THE SAILORS WERE HAVING A GOOD TIME"

[Pg 82]And little Jacob turned his head, and then he scrambled in. Now and then some of the flying fish flew right across the deck of the Industry. And some of them came down on the deck, and some struck against the masts and ropes; and the sailors were standing all about, looking excited, as if they were playing a game. They had their caps in their hands, and[Pg 83] when the fish flew across the deck, they tried to catch them in their caps. And some they caught and some they didn't; but the sailors were having a good time, and they laughed and shouted at their play.

And a sailor who had just caught a fish in his cap brought it to little Jacob.

"Now you can see it plainer," said Captain Solomon.

Little Jacob looked and he saw a fish that was less than a foot long, and the color on its back was a deep, ocean blue, and the fins were a darker blue, and it was all silvery underneath. And it had long fins coming out of its shoulders, almost as long as the fish, and they looked very strong and almost like a swallow's wings.

By and by little Jacob looked up at[Pg 84] Captain Solomon. "Why do the men want to catch so many of them?" he asked. "Because it's fun?"

"Well, no," said Captain Solomon. "It is great fun. I've done it myself, in my day. But these fish are very good to eat. Any kind of fresh meat is a good thing, when you know there's nothing better than salted meat to fall back on. You'll see how good they are, at dinner."

Little Jacob sighed. "Oh," he said. "Thank you for showing me."

And he was rather sober as he went back to his place on the bowsprit to watch. But when dinner time came, he ate some of the flying fish and thought they were very nice, indeed.

And that's all.[Pg 85]

nce upon a time there was a wide river that ran into the ocean, and beside it was a little city. And in that city was a wharf where great ships came from far countries. And a narrow road led down a very steep hill to that wharf, and anybody that wanted to go to the wharf had to go down the steep hill on the narrow road, for there wasn't any other way. And because ships had come there for a great many years and all the sailors and all the captains and all the men who had business with the ships had to go on that narrow[Pg 86] road, the flagstones that made the sidewalk were much worn. That was a great many years ago.

The wharf was Captain Jonathan's and Captain Jacob's and they owned the ships that sailed from it; and, after their ships had been sailing from that wharf in the little city for a good many years, they changed their office to Boston. After that, their ships sailed from a wharf in Boston.

Once, in the long ago, the brig Industry had sailed from Boston for a far country, and little Jacob and little Sol had gone on that voyage. Little Jacob and little Sol were very much interested in the things that they saw every day and in the things that were done every day on the ship by the sailors and by the mates and by[Pg 87] Captain Solomon. But those things that happened the same sort of way, every day, interested little Jacob more than they did little Sol. Little Sol liked to see them a few times, until he knew just what to expect, and then he liked to be out on the bowsprit, seeing the things that he didn't expect; or he liked to be doing things. And the things that he did were the sort of things that nobody else expected. So the things that little Sol did were an amusement to the sailors and to the mates; and sometimes they were an amusement to Captain Solomon and sometimes they weren't. When they didn't amuse Captain Solomon they didn't usually amuse little Sol, either.

Every captain of a ship keeps a sort of diary, or journal, of the voyage that ship[Pg 88] is making. This diary is usually called the ship's log. And every day he writes in it what happened that day; the courses the ship sailed and the number of miles she sailed on each course; the sails that were set and the direction and strength of the wind; and the state of the weather and the exact part of the ocean she was in and the time that she was there.

The exact part of the ocean that the ship is in is usually found by looking at the sun, just at noon, through a little three-cornered thing, called a sextant, that is small enough for the captain or the mate to hold in his hands; and by seeing what time it is, by a sort of clock, when the sun is the very highest. Then the captain goes down into the cabin and does some arithmetic out of a book, using the things[Pg 89] that his sextant had told him, and he finds just exactly where the ship was at noon of that day. Then he pricks the position of the ship on a chart, which is a map of the ocean, so that he can see how well she is going on her course.

Sometimes it is cloudy at noon, so that he can't look at the sun then, but it clears up after dark. Then the captain looks through his sextant at the moon, or at some bright star, and finds his position that way. And sometimes it is cloudy for several days together, so that he can't take an observation with his sextant in all that time. Captains don't like it very well when it is cloudy for several days together, for then they have nothing to tell them just where the ship is, but what is called "dead reckoning."[Pg 90]

Captain Solomon usually had the speed at which the ship was sailing measured several times every day. When he wanted that done, he called a sailor to "heave the log;" and the sailor came and took up a real log, or board, fastened to the end of a long rope, while one of the mates held an hour glass. But there wasn't sand enough in the glass to run for an hour, but it would run for half a minute. And when the mate gave the word, the sailor dropped the log over the stern of the ship and the mate turned the glass. And the sailor held the reel with the rope on it, so that the rope would run off freely, and he counted,[Pg 91] aloud, the knots in the rope as it ran out. For the rope had knots of colored leather in it, and the knots were just far enough apart so that the number of knots that ran out in half a minute would show the number of sea miles that the ship was sailing in an hour. And when the sand in the glass had all run out, the mate gave the word again, and the sailor stopped the rope from running out. So Captain Solomon knew about how many miles the Industry had sailed on each course, and he could put it down in his book.

That wasn't a very good way to tell where the ship was, by adding up all the courses she had sailed and getting her speed on each course, and adding all these to the last place that they knew about,[Pg 92] but, when Captain Solomon couldn't get an observation with his sextant, it was the only way there was. That isn't the way they tell, now-a-days, how many miles a ship has sailed, for there is a better way that gives, more exactly than the old-fashioned "log," the number of miles. But they still have to add up all the courses and the miles sailed on each course to find a ship's place, when they can't take an observation. That is what is called "dead reckoning," and it isn't a very good way at its best.[Pg 93]

"LITTLE JACOB LIKED TO WATCH CAPTAIN SOLOMON"

"LITTLE JACOB LIKED TO WATCH CAPTAIN SOLOMON"

[Pg 94]Little Jacob liked to watch Captain Solomon writing up the log for the day. He always wrote it just after dinner. And when he had finished dinner, he would get out the book and clear a place on the table to put it; and then he took a quill[Pg 95] pen in his great fist and wrote, very slowly, and with flourishes. And when he had it done he always passed the book over to little Jacob.

"There, Jacob," he said, with a smile. "That please you?"

"Oh, yes, sir," answered little Jacob. "Thank you, sir." And he began to read.

One day, when they had been out of Boston about three weeks, little Jacob watched Captain Solomon write up the log, and, when he got it, he thought he would turn back to some days that he knew about and read what Captain Solomon had said about them. And so he did.

October 2, 1796. 8 days out. Comes in fresh gales & Flying clouds. Middle & latter part much the same, with all proper sail spread. Im[Pg 96]ploy'd varnishing Deck and scraping Foreyard. Saw a Brig and two Ships standing to the N. & W. A school of porpoises about the ship a good part of the Morning, of which the Crew harpooned a good number and got them on deck. I fear they are too many for us to acct. for before they go Bad.

Course ESE 186 miles. Wind fresh from S. & W. Observatn, Lat. 34 20 N. Long. 53 32 W.

That didn't seem to little Jacob to be enough to say about the porpoises. He sighed and turned to another day.

October 5, 1796. 11 days out. Comes in Fresh breezes and a rough sea fr. S. & E. Spoke Brig Transit of Workington fr.—S. Salvador for Hamburg. Middle & latter part moderate with clear skies and beautiful weather. Ran into some weed and running threw it off and on all day.[Pg 97]

| Courses | ESE 98 m. | Wind strong fr. N. & E., |

| moderating to gentle airs. | ||

| SSE. 54 m. | Observatn., | |

| —— | Lat. 30 22 N. Long. 47 30 W. | |

| 152 |

And it seemed to little Jacob that it was a shame to say no more than that about that strange Seaweed Sea and the curious things that were to be found in it. But it was Captain Solomon's log and not little Jacob's. He turned to another day, to see what there was about the flying fish.

October 11, 1796. 17 days out of Boston. Comes in with good fresh Trades and flying clouds. Middle & latter part much the same. Saw a ship standing on our course. Not near enough to speak her. At daylight passed the ship abt. 5 miles to windward. All proper sail spread.

Great numbers of Flying Fish (Sea Swallows)[Pg 98] all about the ship, and the men imploy'd in catching them. It gave the men much pleasure and a deal of sport and the Fish very good eating.

Course SSE 203 miles. Wind NE. strong, Trades. Observatn., Lat. 18 10 N. Long. 37 32 W.

Chronometer loses too much.

Took Spica and Aquila at 7 p. m., Long. 35 30 W.

Little Jacob didn't know what Spica and Aquila were, and he asked Captain Solomon.

"They are stars, Jacob, and rather bright ones," said Captain Solomon. "My chronometer—my clock, you know—was losing a good deal, and I looked through my sextant at them to find out where we really were."

"Oh," said little Jacob; but he didn't understand very well, and Captain Solomon[Pg 99] saw that he didn't. It wasn't strange that he didn't understand.

Little Jacob sat looking at the log book and he didn't say anything for a long time.

Captain Solomon smiled. "Well, Jacob," he said, at last, "what are you thinking about? I guess you were thinking that you wished that you had the log to write up. Then you could say more about the things that were interesting. Weren't you?"

Little Jacob got very red. "Oh, no, sir," he said. "That is, I—well, you see, the things that are new and interesting to me—well, I s'pose you have seen them so many times that it doesn't seem worth while to you to say much about them."

"That is a part of the reason," answered Captain Solomon. "The other part is[Pg 100] that it doesn't seem necessary. Anything that concerns the ship is put down. We don't have time—nor we don't have the wish—to put down anything else."

"Of course," said little Jacob, "it isn't necessary."

"I'll tell you what I'll do, Jacob," said Captain Solomon. "I'll let you write up the log, and then you can write as much as you like about anything that interests you."

Little Jacob got very red again. "Oh!" he cried, getting up in his excitement. "Will you let me do that? Thank you. I thank you very much. But—but how shall I put down all those numbers that show how the ship goes?"

"I'll give you the numbers, as you call them," said Captain Solomon, "and I'll[Pg 101] look over the log every day, to see that you put them down right."

"I'll put them down just exactly the way you tell me to," said little Jacob. "And I thank you very much. And I—I write pretty well."

And little Jacob ran to find little Sol and to tell him about how he was going to write the log of the voyage, after that. And he did write it, numbers and all, and it was a very interesting and well written log. For little Jacob could write very well indeed; rather better than Captain Solomon. Captain Solomon knew that when he said that little Jacob could write it.

And that's all.[Pg 102]

nce upon a time there was a wide river that ran into the ocean, and beside it was a little city. And in that city was a wharf where great ships came from far countries. And a narrow road led down a very steep hill to that wharf, and anybody that wanted to go to the wharf had to go down the steep hill on the narrow road, for there wasn't any other way. And because ships had come there for a great many years, and all the sailors and all the captains and all the[Pg 103] men who had business with the ships had to go on that narrow road, the flagstones that made the sidewalk were much worn. That was a great many years ago.

The wharf was Captain Jonathan's and Captain Jacob's, and they owned the ships that sailed from it; and, after their ships had been sailing from that wharf in the little city for a good many years, they changed their office to Boston. After that, their ships sailed from a wharf in Boston.

Once the brig Industry had sailed for a far country. Little Jacob and little Sol had gone on that voyage, and they always raced through their breakfast so that they could get out on deck and see what there was to see. Little Sol generally beat and went on deck first, but sometimes little Jacob was first. The reason that little[Pg 104] Sol generally beat was that little Jacob had been brought up not to hurry through his meals, but to wait for the older people; and he had to wait, anyway, because he couldn't get the second part until his father and his mother, and any company they had, had finished the first part. Then the first part was carried out and the second part was brought in; and little Jacob had to sit quietly in his chair with his hands folded in his lap until it came in. But little Sol didn't bother much about those things.

One morning little Jacob and little Sol had raced through breakfast, as they always did, and they had finished at exactly the same time, because little Jacob hurried. Then they both tried to go on deck at the same time. They managed to go[Pg 105] up the cabin steps together, but they couldn't get through the door together without squeezing very tightly. And, in that squeezing, little Jacob caught his jacket on the lock of the door so that the jacket tore. But little Jacob didn't know it, and he kept on pushing, and at last he and little Sol went bouncing out and fell sprawling on the deck.

Captain Solomon was sitting in the cabin, and he laughed to see them go sprawling out, but he thought that he guessed the little boys had done enough of that racing business. For somebody would have to mend little Jacob's jacket and, besides, there was danger that little Jacob would forget his manners, and that would never do. Little Jacob had beautiful manners. So Captain Solomon made[Pg 106] up his mind that Sol would have to wait until little Jacob finished his breakfast, after that, and then they should go up the cabin steps like little gentlemen and not push and crowd and tear their jackets. And that would be a good thing for little Sol, too, but he wouldn't like it at first. Captain Solomon didn't care whether he liked it or not.

The little boys didn't know what Captain Solomon was thinking about, and they laughed and picked themselves up and looked around. And they didn't see anything but water all about, and the bright sunshine, and one or two little hilly clouds, and all the many sails of the Industry. For they were still in the trade winds where it is generally good weather. And they saw the mate, and he was stand[Pg 107]ing at the stern and looking down into the water behind the ship.

"Let's see what Mr. Steele is looking at," said little Sol.

"All right," said little Jacob, "let's."

So the two little boys walked to the stern and leaned on the rail and looked down at the water. But first little Jacob said "Good morning" to the mate.

"Good morning, Jacob," said the mate. "Now, what do you see there?"

"I know," cried little Sol. "It's a shark."

"Oh, is it?" cried little Jacob. He was very much interested and excited. "Where is it, Sol?"

Little Sol pointed. "Right there," he said. "You can see his back fin, just as plain."[Pg 108]

And little Jacob looked again, and he saw all the little swirls and bubbles and foam that made the wake of the ship, and right in the middle of it all he saw a great three-cornered thing sticking up out of the water. It was dark colored, and it followed after the ship as if it were fastened to it.[Pg 109]

"'RIGHT THERE,' HE SAID, 'YOU CAN SEE HIS BACK FIN.'"

"'RIGHT THERE,' HE SAID, 'YOU CAN SEE HIS BACK FIN.'"

[Pg 110]"Is that his back fin?" asked little Jacob, "that three-cornered thing? I don't see the rest of him."

"If you look hard," said Mr. Steele, "you'll make him out. He's clear enough to me."

Little Jacob looked hard and at last he saw the shark himself; but there were so many bubbles and swirls, and the shark was colored so exactly like the water, as he looked down into it, that it wasn't[Pg 111] easy to see him. Both the little boys watched him for some time without saying anything.

At last little Jacob sighed. "He's pretty big," he said. "Why do you suppose he follows the ship that way? It's just as if we were towing him."

"Well," said the mate, "I never had a chance to ask any shark that question—and get an answer—but I think it's to get what the cook throws overboard." The mate turned and looked forward. "I see the cook now, with a bucket of scraps. You watch Mr. Shark."

Little Jacob and little Sol both looked and they saw the cook walking from the galley with his bucket. The galley is the kitchen of the ship. And he emptied the bucket over the side. Then the two little[Pg 112] boys looked quickly at the shark again, to see what he would do.

They saw the shark leave his place at the stern of the Industry as the things came floating by, and they saw him turn over on his side and eat one or two of the things. He took them into his mouth slowly, as though he had plenty of time; or it seemed as if he ate them slowly. Really, he didn't. They lost sight of him, for he stayed at that place until every scrap was gone.

Little Jacob smiled. "He doesn't have to race through his breakfast," he said, "does he, Sol? Did you see that his underneath parts were white? I wonder why that is. I s'pose it's because anything that looks down looks into darkness, and anything that looks up[Pg 113] looks into lightness. Is that why, Mr. Steele?"

"So that the fish wouldn't see him coming?" asked Mr. Steele. "Well, Jacob, to tell you the truth, I never thought much about it. And I don't really know how a shark would look from underneath, in the water. The pearl divers in India could tell you. But I guess that comes as near to the reason as any other—near enough, anyway. I've no doubt that his coloring makes him very hard to see, in the water."

"I would like to see the pearl divers," said little Jacob, "but I s'pose I can't. And I'm rather glad the shark is gone."

"Huh!" said little Sol. "He isn't gone. He only stopped a minute. He'll be back. Won't he, Mr. Steele?"[Pg 114]

Mr. Steele smiled. "There he comes, now."

And the boys looked and they saw the three-cornered fin cutting through the water at a great rate. The shark caught up with the ship easily and took his old place, just astern.[Pg 115]

The shark stayed with the Industry all of that day, and little Jacob watched him once in a while. He thought the shark was kind of horrible and he wished that he would go away. But he didn't, that day or that night, or the next. And Captain Solomon didn't like it, either.

So, when Captain Solomon saw him on the third morning, he spoke to the mate.

"Better get rid of that fellow, Mr. Steele," he said. "Got a shark hook?"

"Yes, sir," answered the mate. "But I'm afraid it isn't big enough for him."

But Captain Solomon told him to try it, anyway. And he called some of the sailors and told them to rig a tackle on the end of the mainyard. That was so that it would be easy to haul the shark in, when they hooked him. And he went down and got[Pg 116] the shark hook. It was a great, enormous fishhook and it had about a yard of chain hitched to it, because if it was rope that went in the shark's mouth, he might bite it off. And a large rope ran through the blocks of the tackle, and the sailors hitched the end of that rope to the end of the chain. A lot of sailors took hold of the other end of the rope, and they stood with the rope in their hands ready to run away with it, just as they did when they were hoisting a yard with a sail.

Then the cook came with a big chunk of fat salt pork, and he put it on the hook so that the point of the hook was all covered. And the mate looked at it, to see if it was done right, and he saw that it was.

"Slack away on the line," he called to the sailors.[Pg 117]

And they let out the rope, until the mate thought that there was enough let out, and then he threw the hook, that was baited with the salt pork, overboard, and it trailed out astern.

The shark saw the pork and he left his place at the stern and went over to see about it. First he seemed to smell of it and make up his mind that it was good to eat. Then he turned lazily over upon his side, showing his whitish belly, and opened his mouth and swallowed the pork, with the hook inside it, and nearly all of the chain. Little Jacob was watching him, and he saw that the shark's mouth was not at the end of his nose, as most fishes' mouths are, but it was quite a way back from his snout, on the under side. And he saw his teeth quite clearly. There were[Pg 118] a great many of them, and they seemed to be in rows. Little Jacob didn't have time to count the rows, but he thought that the teeth looked very cruel. The shark's mouth was big enough to take in a man whole. And then the mate, who still had his hand on the rope, jerked it with all his might.

What happened then was never quite clear to little Jacob. He heard the sailors running away with their end of the rope and shouting a chanty and stamping their feet. And he saw the water alongside the ship being all foamed up by an enormous monster that seemed large enough for a whale. Then some water came up from the ocean and hit him in the face, so that he couldn't see for a few minutes and his jacket was all wet through. But the noise kept on.[Pg 119]

When little Jacob could see again, the enormous monster was half out of the water and rising slowly to the yard-arm, while he made a tremendous commotion with his tail in the water, and a sailor was just reaching out with an axe. The sailor struck twice with the axe, but little Jacob didn't see where. Then the shark dropped back into the ocean with a great splash and out of sight.

"Well!" said the mate. "He's a good one! Took a good shark hook with him and pretty near a fathom of new chain!"

And when little Jacob had got his breath back again, he ran down into the cabin to write all about the shark in the log-book.

And that's all.[Pg 120]

nce upon a time there was a wide river that ran into the ocean, and beside it was a little city. And in that city was a wharf where great ships came from far countries. And a narrow road led down a very steep hill to that wharf and anybody that wanted to go to the wharf had to go down the steep hill on the narrow road, for there wasn't any other way. And because ships had come there for a great many years and all the sailors and all the captains and all the men who had business with the ships had[Pg 121] to go on that narrow road, the flagstones that made the sidewalk were much worn. That was a great many years ago.

The wharf was Captain Jonathan's and Captain Jacob's and they owned the ships that sailed from it; and, after their ships had been sailing from that wharf in the little city for a good many years, they changed their office to Boston. After that, their ships sailed from a wharf in Boston.

Once, in the long ago, the brig Industry had sailed from Boston for far countries, and she had been gone about three months. She was going to Java, first, to get coffee and sugar and other things that they have in Java; and then she was going to Manila and then back to India and home again. It was almost Christmas time. Little Jacob and little Sol were on board the[Pg 122] Industry on that voyage, and it seemed very strange to them that it should be hot at Christmas time. But they were just about at the equator, or a little bit south of it, and it is always hot there; and besides, it is summer at Christmas time south of the equator. So little Jacob and Sol had on their lightest and coolest clothes, and they had straw hats on; but they didn't run about and play much, it was so hot.