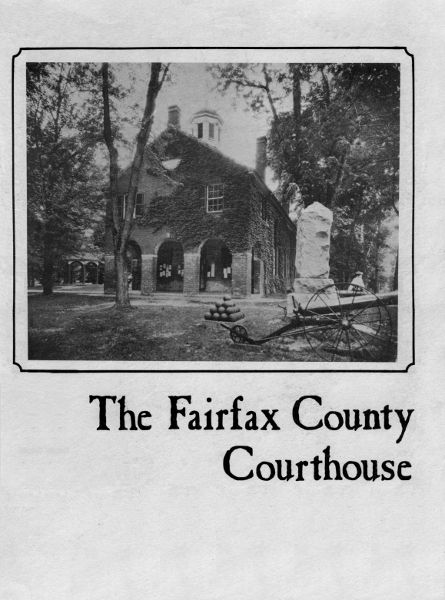

Front cover—The old courthouse about 1920. Copy courtesy Lee

Hubbard.

Front cover—The old courthouse about 1920. Copy courtesy Lee

Hubbard.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Fairfax County Courthouse, by

Ross D. Netherton and Ruby Waldeck

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Fairfax County Courthouse

Author: Ross D. Netherton

Ruby Waldeck

Release Date: May 10, 2009 [EBook #28750]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE FAIRFAX COUNTY COURTHOUSE ***

Produced by Mark C. Orton, Chris Logan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

BY

ROSS D. NETHERTON

AND

RUBY WALDECK

Published by the Fairfax County Office of Comprehensive Planning

under the direction of the County Board of Supervisors

in cooperation with the Fairfax County History Commission

July 1977

The following history publications are available from:

Fairfax County Administrative Services

Fairfax Building

10555 Main Street

Fairfax, Va. 22030

703-691-2781

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 77-84441

This monograph is one of a series of research reports on the historical and architectural landmarks of Fairfax County, Virginia. It has been prepared under the supervision of the Fairfax County Office of Comprehensive Planning, in cooperation with the Fairfax County History Commission, pursuant to a resolution of the Board of County Supervisors calling for a survey of the County's historic sites and buildings.

The authors of this report wish to acknowledge with thanks the assistance of Lindsey Carne, Mrs. J. H. Elliott, Lee Hubbard, Mrs. Jean Johnson Rust, and Mrs. Barry Sullivan, who provided information and graphics for this publication. Also valuable were the comments of the Honorable James Keith, Circuit Court Judge; Mrs. Edith M. Sprouse; John K. Gott; Mrs. Catharine Ratiner; and Mayo S. Stuntz, all of whom reviewed the manuscript with care prior to its final revisions.

Special thanks are tendered to the Honorable Thomas P. Chapman, Jr. and the Honorable W. Franklin Gooding, former Clerks of the Courts of Fairfax County; the Honorable James Hoofnagle, present Clerk of the Courts; and to Walter M. Macomber, architect of the 1967 reconstruction of the original wing of the courthouse, who granted extensive interviews which filled many of the gaps created by lack of documentary sources.

Throughout the entire research and writing of this report, the authors received valuable guidance and comments from the members of the Fairfax County History Commission and assistance from the staffs of the Fairfax County Public Library and the Virginia State Library.

Finally, the authors acknowledge with thanks the help of Jay Linard, Mrs. Verna McFeaters, Ms. Virginia Inge, Ms. Irene Rouse, Ms. Annette Thomas, and Ms. Robin Pedlar in manuscript preparation.

Ross Netherton

Ruby Waldeck

The Fairfax County Courthouse is an important addition to the historical record of Fairfax County, Virginia. It brings together in one volume a history of the Fairfax County Courthouses and a manual of the organization and operation of governmental affairs centered within them over the years. A particular insight with regard to the early years of the county is evident.

Dr. Netherton and Mrs. Waldeck describe the consequential role the courthouse enjoyed as a social center as they examine the governmental role which made it the centerpiece of Fairfax County. The reader will note that the early Fairfax County officials gained an understanding of the importance of democratic government in our nation through their participation in county government while the people they served developed a sense of community through their interaction at the courthouse. The present courthouse stands as a monument to the governmental and social prosperity Fairfax County has enjoyed.

This text documents the story of the building which has stood at the center of almost two centuries of political life in Fairfax County. The extensive footnotes will prove an invaluable aid to scholars exploring the history of the county. History students in our county's schools will find The Fairfax County Courthouse an important addition to their reading lists. We are all indebted to Ross Netherton and Ruby Waldeck for their contribution in casting such a revealing light upon the roots of Fairfax County, her people and government.

James E. Hoofnagle

Clerk of the Fairfax County Court

Each generation of Americans has acknowledged its debt to Virginia's leaders whose skill in politics was demonstrated so well in a half-century that saw independence achieved and a new republic established. They were products of a system of government which itself had been perfected over more than 150 years before the colonies declared their independence. To these men—George Washington, George Mason, Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, John Marshall, George Wythe, James Madison, and the Carters—the County court was an academy for education in the art of government. Important as it was to sit in the House of Burgesses at Williamsburg, the lessons of politics and public administration were learned best in the work of carrying on the government of a county. Virginia counties were unique in colonial history, for the considerable degree of autonomy enjoyed by the County courts gave them both a taste of responsibility for a wide range of public affairs and a measure of insulation from the changes of political fortune which determined events in Williamsburg, and later Richmond.

In Virginia, the county courthouse was the focal point of public affairs. Usually built in a central location, with more regard for accessibility from all corners of the county than for proximity to established centers of commerce, the courthouse came to be a unique complex of buildings related to the work of the court. In time, most of these clusters of buildings grew into towns or cities, but throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries many places shown on Virginia maps as "Court House" consisted literally of a county courthouse and its related structures standing alone beside a crossroads.

On court days, however, the scene changed. The monthly sessions of the court, conducted in colonial times by the "Gentleman Justices", provided opportunities to transact all manner of public business—from issuing licenses and collecting taxes to hearing litigation and holding elections. They also were social events and market days; there people came to meet their friends, hear the news, see who came circuit-riding with the justices, sell their produce, and buy what they needed.

In the two centuries since independence, profound changes have occurred in all phases of life that were centered in the courthouse. In Fairfax County, the pace and extent of[Pg 2] these changes have been extensive. Architectural historians who note uniqueness in the fact that Virginia courthouses developed as a complex of related buildings may see ominous symbolism in the fact that today one of the structures in the cluster around Fairfax County's courthouse is a modern fifteen-story county office building. Yet, at the same time this office building was being planned, workmen were rehabilitating the original section of the courthouse to represent its presumed appearance in an earlier time, thus providing a reminder of the historic role of county government in Virginia.

| Five Colonial Justices of the Fairfax County Court | |

George Mason.

George Mason.

|

George Washington.

George Washington.

|

Bryan, later eighth Lord Fairfax.

Bryan, later eighth Lord Fairfax.

|

Thomas, sixth Lord Fairfax.

Thomas, sixth Lord Fairfax.

|

George William Fairfax.

George William Fairfax.

|

FAIRFAX COUNTY'S EARLY COURTHOUSES, 1742–1800

Once the survival of the colony of Jamestown seemed assured, provision for the efficient and orderly conduct of public affairs received attention. The Jamestown colonist and his backers in the Virginia Company of London were familiar with county government structure in England, and from early colonial times the county was the basic unit of local government in Virginia.

In the concept of county government, the role of the county court was central. As early as 1618, Governor Sir George Yeardley established the prototype of the County Court in his order stating that "A County Court be held in convenient places, to sit monthly, and to hear civil and criminal cases."[1] The magistrates or justices who comprised the court were, as might be expected, the owners of the large plantations and estates in the vicinity, and all were used to administering the affairs of the people and lands under their control. Accordingly, administrative duties as well as judicial duties were given to the court, and the justices' responsibilities included such matters as the issuance of marriage licenses, the planning of roads, and assessment of taxes.[2]

Colonial Virginia statutes specified that each county should "cause to be built a courthouse of brick, stone or timber; one common gaol, well-secured with iron bars, bolts and locks, one pillory, whipping post and stocks."[3] In addition, the law authorized construction of a ducking stool, if deemed necessary, and required establishment of a 10-acre tract in which those imprisoned for minor crimes might, on good behavior, walk for exercise. In addition, buildings were customarily provided to house the office of the Clerk of the Court, and to accommodate the justices of the assize and their entourage of lawyers and others who accompanied them as they rode circuit among the counties of the colony. In England, the "assizes" were sessions of the justices' courts which met, generally twice a year in each shire, for trial of questions of fact in both civil and criminal cases. The county courts in colonial Virginia continued to be called assizes for much of the 18th Century.

When events moved toward the partition of Prince[Pg 4] William County to create the County of Fairfax, the Journal of the Governor in Council in Williamsburg recorded the following entry:

Saturday, June ye 19th, 1742

. . . .

ORDERED that the Court-house for Fairfax County be appointed at a place call'd Spring Fields scituated between the New Church and Ox Road in the Branches of Difficult Run, Hunting Creek and Accotinck.[4]

Whether this was the first seat of the Fairfax County Court is not positively known. It is possible that the first sessions of the court may have been held at Colchester. Although no records of the transactions at these sessions have been found, an early history of the County cites entries in an early deed book which order the removal of the County Court's records from Colchester to a new courthouse more centrally located in the county.[5]

Be this as it may, the plan to establish a courthouse which was formalized by the Governor in Council apparently was deliberately designed to accommodate the increasing settlement of areas inland from the river plantations—an interest which the Proprietor, Thomas sixth Lord Fairfax, shared.

"Spring Fields", the site of the court house, was part of a tract of 1,429 acres owned in 1740 by John Colvill, and conveyed by him in that year to William Fairfax.[6] In this tract were numerous springs forming the sources of Difficult Run, Accotinck Creek, Wolf Trap Run, Scott's Run and Pimmit Run. It was high ground, comprising part of the plateau area of the northern part of the County, and the site selected for the courthouse had a commanding view for many miles around.

The location specified in the Council Order was on the New Church Road (later known variously as the Eastern Ridge Road, the Alexandria-Leesburg Road, or the Middle Turnpike) running from the Falls Church to Vestal's Gap in the Blue Ridge Mountains, at a point where this road intersected the Ox Road, running north and west from the mouth of the Occoquan River. A map of 1748 also shows roads running from the courthouse west in the direction of Aldie, and southwest toward Newgate (now called Centreville).[7] The site was roughly equidistant for persons coming from Alexandria,[Pg 5] Newgate, and the Goose Creek settlements, but somewhat farther for those from Colchester.

The land on which courthouse was built was conveyed to the County by deed from William Fairfax, dated September 24, 1745,[8] and described six acres "where the court house of the said county is to be built and erected," to be held by the County "during the time the said Court shall be located there but no longer." According to a survey made in March 1742, the site was a rectangle, 40 poles long by 24 poles wide, described in metes and bounds starting from a post on the west side of "Court House Spring Branch".[9] No other landmarks or monuments capable of surviving to modern times were mentioned in the deed, and today the site of the Springfield Courthouse can be determined as approximately one-quarter mile south and west of Tyson's Corner.

Having in mind the statutory requirements, it is presumed that the complex of buildings at Springfield consisted of a courthouse, a jail with related structures, a clerk's office, and one or more "necessary houses" (outhouses), all conveniently located with respect to each other and the roads. County records show surveys for two ordinaries (inns) located on or adjacent to the courthouse tract. One of these, surveyed in 1746, was a two-acre parcel containing John West's ordinary and related buildings, and the other, also surveyed in 1746, was for one acre within the courthouse tract on which John Colvill was allowed to build an ordinary.

No contemporary descriptions of the courthouse have survived, but it is likely that the buildings were of log construction, on stone foundations, with brick chimneys. A 16-foot-square addition to the courthouse was ordered in 1749, with the specification that it have a brick chimney.[10] An item from the Court Order Book, dated December 23, 1750, states:

On motion of the clerk of the court that papers lying on the table

are frequently mixed and confused, and many times thrown down by

persons crowding in and throwing their hats and gloves on the said

table, the ill consequences thereof being considered, it is

ordered that Charles Broadwater, Gent. agree with some workman to

erect a bar around the said clerk's table for the[Pg 6]

[Pg 7] better

security of the books and papers.[11]

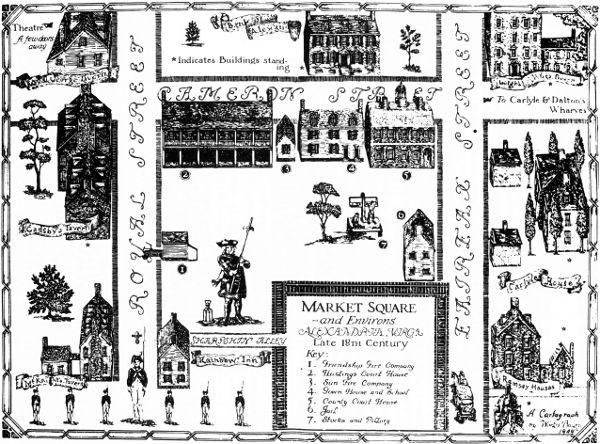

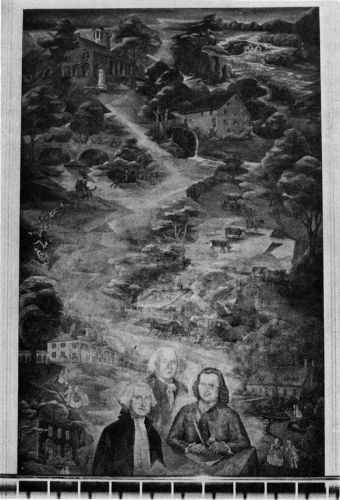

Cartograph of the Market Square and Fairfax County

Courthouse in Alexandria, as they might have appeared in the

eighteenth century. Drawn by Worth Bailey, 1949.

Cartograph of the Market Square and Fairfax County

Courthouse in Alexandria, as they might have appeared in the

eighteenth century. Drawn by Worth Bailey, 1949.In 1750, Fairfax County's western border closely approached the edge of English settlement in Virginia. Settlements in the western part of the County were growing far less rapidly than in the centers of population in the eastern part. Alexandria, established as a town in 1749, showed signs of becoming a major seaport, and its merchants complained that travel to the courthouse at Springfield was burdensome, and that service of process and execution of writs was well-nigh impossible.[12] They actively campaigned for moving the courthouse to Alexandria, and overcame the opposition of the "up-country" residents by offering to provide a suitable lot and build a new courthouse in Alexandria.

Alexandria prevailed in 1752, and the records of the colonial Governor in Council showed the following entries:

March 23, 1752. A petition subscribed by many of the principal inhabitants of Fairfax County for removing the court house and prison of that county to the town of Alexandria, which they propose to build by subscription, was this day read, ORDERED that the justices of the said county be acquainted therewith and required to signify their objection against such removal, if they have any, by the 25th of next month, on which day the Board will resume the consideration thereof.

And:

April 25, 1752. Upon the petition of many of the inhabitants of Fairfax County for removing the court house and prison of the said county by subscription to the town of Alexandria, the Board being satisfy'd that it is generally desired by the people, and on notice given, no objection being made to it, ORDERED that the court house and prison be removed accordingly to the town of Alexandria.[13]

By May 1752, the County Court's Minute Book carried the final record of business transacted at the Spring Fields Courthouse.

In Alexandria, the townspeople set aside two lots in the block of the original town survey bounded by Fairfax[Pg 8] Street, Cameron Street and King Street.[14] By ordinance, all buildings in the town had to face the street and have chimneys of brick or stone, rather than wood, to prevent fires.[15] The building erected as the new courthouse faced Fairfax Street, between Cameron and King Streets. A prison was built behind the courthouse building in the dedicated lots. The gallows, however, are said to have remained at Spring Fields for some time.[16]

Neither the architect nor the builder of the courthouse at Alexandria are known, although there is evidence that John Carlyle helped with the building of both the courthouse and market square.[17]

In the last half of the eighteenth century, Alexandria prospered as the principal seaport of the Northern Neck. Its wharves and warehouses were busy, and its politics were enlivened by the presence of some of the colonies' most distinguished residents and visitors. As tobacco gave way to diversified farming, wheat and flour comprised two of Alexandria's major commodities of trade, and enforcement of the flour inspection and marking laws became an important governmental function. Criminal justice was dispensed publicly in the courthouse and jail yard, furnishing moral lessons for both the culprits and observing crowds. It was in this jail, too, that tradition has it Jeremiah Moore, a dynamic Baptist minister of colonial Virginia, delivered a sermon to crowds outside his cell window while he was confined for preaching without a license.[18]

The court records for the years 1752 to 1798 show the names of many Virginians who were leaders in the War of Independence and the subsequent establishment of the new state government. Independence did not significantly affect the judicial system, however, and, except for their new allegiance, state and local officials conducted public business much as they had in the 1760's.

During the years of war, however, the courthouse suffered substantially because of lack of maintenance. After the war, repairs frequently were postponed due to arguments over whether the state or locality should raise the money for them. Thus, the court records of the post-war period show frequent references to the need for repairs on the courthouse and jail,[19] most, apparently, without success.

There were more serious questions being raised about[Pg 9] the future of the courthouse in Alexandria's market square. Alexandria no longer was central to the County's most important interests. Its port was losing trade to rivals, principally Baltimore, and the voice of the growing numbers of settlers in the western part of the county complained that Alexandria merchants gained at the expense of others by having the court meet in their town. George Mason of Gunston Hall felt that Alexandria politicians were building up too strong a hold on the machinery of County government, and sought the aid of members of the General Assembly to arrange for changing the location of the courthouse.[20] Finally, in 1798, the Virginia General Assembly directed that Fairfax County's Court House be relocated to a site closer to the center of the County.[21]

The search for a suitable site had gone on for almost ten years previously and might not have been concluded even then if its urgency had not been sharpened by the passage of Congressional legislation leading to creation of the District of Columbia, and the threat that Alexandria would fall within the boundaries of the new Federal capital. Since by law the County Court could not meet outside the boundaries of the County, no further delay could be permitted. Land was acquired, a new courthouse was built, and the County Court moved into its new quarters early in 1800.[22]

[1] Albert O. Porter, County Government in Virginia, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1947), p. 13.

[2] A Hornbook of Virginia History, (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1965), p. 64.

[3] Virginia, Laws, 1748, c. 7, revising earlier statutes on courts enacted in 1662 and 1679.

[4] Wilmer Hall (Ed.), Executive Journals of the Council of Colonial Virginia, (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1945), V. 93.

[5] Industrial and Historical Sketch of Fairfax County, (Fairfax: County Board of County Supervisors, 1907), p. 45.

[6] Northern Neck Grants Book, Liber E, p. 182. William Fairfax was a cousin of the Proprietor, and acted as his agent.

[7] The so-called Truro Parish Partition Map, purporting to lay out boundaries for a division of Truro Parish to create a new parish for the western settlements. See Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, XXXVI, 180.

[8] Fairfax County Deed Book, Liber A, No. 2, p. 494.

[9] Fairfax County Deed Book, Liber A, Pt. 1, p. 52, Survey, March 17, 1742.

[10] E. Sprouse (ed), Fairfax County Abstracts: Court Order Books, 1749–1792, citing Order Book, 1749–54, December 26, 1749, p. 49.

[11] Ibid., p. 131. Charles Broadwater was one of the justices.

[12] There was some reason to support this, apparently, for in 1748 the General Assembly reduced the number of court meetings to four per year for these reasons. See Virginia, Laws, 1742, c. 32; Laws, 1748, c. 59; Laws, 1752, c. 7.

[13] Virginia Gazette, reprinted in William & Mary Quarterly, XII, 215.

[14] [Pg 11]Cited in Mary G. Powell, The History of Old Alexandria, Virginia from July 13, 1749 to May 24, 1861, (Richmond: William Byrd Press, 1928), p. 35.

[15] Ibid., p. 22.

[16] Jeanne Rust, History of the Town of Fairfax, (Washington: Moore & Moore, 1960), p. 30.

[17] Gay M. Moore, Seaport on the Potomac, (Richmond: Garrett & Massie, 1949), p. 12.

[18] William C. Moore, "Jeremiah Moore: 1746–1815," William & Mary Quarterly, 2d ser., XIII, 18, 21. Tradition also holds that Jeremiah Moore was defended by Patrick Henry, but this has not been verified.

[19] Robert Anderson, "The Administration of Justice in the Counties of Fairfax, and Alexandria and the City of Alexandria", Arlington Historical Magazine, II, No. 1 (October 1961), 19–21.

[20] "Letters of George Mason to Zachariah Johnston", Tyler's Quarterly Review, V (January 1924), 189.

[21] Virginia, Laws, 1797–98, c. 37; Shepherd, Statutes at Large, II, 107.

[22] During the 1780's the court was compelled to leave the original courthouse building for temporary quarters. Harrison, Landmarks, p. 343, states that during this period the County Court met in the Alexandria Town House, located next door, which also housed the Hustings Court. He also states that the Clerk of the County Court set up his offices in a nearby school building. The Alexandria Gazette, November 13, 1878, reported the demolition of an old house on the south side of Duke Street, east of St. Asaph's Street, which it stated had served as the office of the Clerk of Alexandria's Hustings Court and the Fairfax County Court commencing in the spring of 1793.

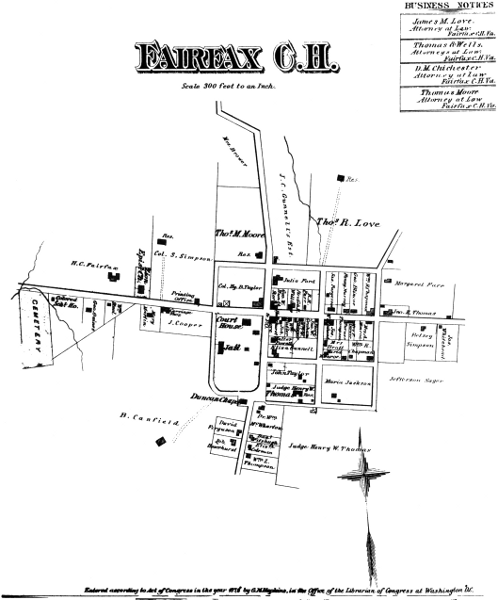

THE PROVIDENCE COURTHOUSE AND ITS RELATED BUILDINGS: 1800–1860

The resolution of the General Assembly ordering relocation of the courthouse was not specific as to the site on which it would be built. Accordingly, in May 1790, the court appointed a commission to inspect a site near Ravensworth, within a mile of the crossroads at Price's Ordinary, and to negotiate for purchase of a two-acre parcel.[23] The commissioners' report was not favorable to the site, however, and negotiations for other land continued until, in May 1798, a group of commissioners was appointed to inspect a site at Earp's Corner (between a road which later became the Little River Turnpike and the Ox Road), owned by Richard Ratcliffe.[24] The commissioners reported favorably, and Ratcliffe was persuaded to sell four acres to the County for one dollar. A sale was made, and the deed recorded on June 27, 1799.[25]

Work had begun on the new courthouse some six months earlier, as indicated by the following notice appearing in the Columbia Mirror and Alexandria Advertiser:

The Fairfax Court House Commissioners have fixed on Thursday the 28th instant for letting out the erection of the necessary Public Buildings to the lowest bidder. As they have adopted the plan of Mr. Wren, those workmen who mean to attend may have sight of the plan.

Charles Little

David Stuart

William Payne

James Wren

Charles Minor[26]

The successful bidders at this event were John Bogue, a carpenter and builder newly arrived in the United States, and his partner, Mungo Dykes. They completed the construction of the courthouse late in 1799, and on January 27, 1800, the Commissioners reported to the County Court that they had received the "necessary buildings for the holding of the Court", and found them "executed agreeably to the contract".[27]

[Pg 13]Within the four-acre courthouse tract, a half-acre was laid off to provide space to build an office for the Clerk of the Court.[28] This original tract did not provide enough ground for the jail yard and other grounds comprising the courthouse compound.[29] Accordingly, in March 1800 the Court ordered William Payne to prepare a new survey of the compound, enlarged to accommodate all of the facilities required by the law. The area of this new survey was ten acres, capable of accommodating courthouse, jail, clerk's office, gallows and pillory, a stable, a storehouse and possibly an ordinary.[30]

The equipping of the courthouse and transfer of the court's records were accomplished by March 1800, so that the Columbia Mirror and Alexandria Advertiser was able to carry a notice its March 29th edition that

The County Court of Fairfax is adjourned from the town of Alexandria to the New Court House, in the Center of the County, where suitors and others who have business are hereby notified to attend on the 3d Monday in April next.

Thus, the first recorded meeting of the court in the new courthouse was on April 21, 1800.[31] Meanwhile, in Alexandria, the Mayor and Council adopted a resolution giving to Peter Wagener the title to the bricks of the old courthouse on Alexandria's market square as indemnity for pulling it down.[32]

The central location of the new courthouse and the improvement of its accessibility through the construction of several turnpike roads commencing in the early 1800's, led naturally to the growth of a community around the courthouse. In the vicinity of the crossroads a few buildings antedated the courthouse. Earp's store, probably built in the late 1700's, was one such building, as were dwelling houses reputedly built by the Moss family and Thomas Love.[33]

Development of more nearby land was not long delayed. In 1805 the General Assembly authorized establishment of a new town at Earp's store, to be named Providence.[34] The future growth of the town was forecast in a plat laying off a rectangular parcel of land adjacent to the Little River Turnpike into nineteen lots for building.[35]

[Pg 14]Settlement during the next few decades was relatively slow. Rizen Willcoxen built a brick tavern across the turnpike from the courthouse.[36] A variety of "mechanics" and merchants opened their workshops and stores to serve the local residents and travellers on the turnpike, and, on the north side of the turnpike, a store was established by a man named Gerard Boiling.[37] Also, a school for girls occupied land across the turnpike from the present Truro Episcopal Church, and, east of the courthouse crossroads, a Frenchman named D'Astre built a distillery and winery and developed a vineyard.[38]

Martin's 1835 Gazetteer of Virginia and the District of Columbia described Fairfax Court House Post Office as follows: "In addition to the ordinary county buildings, some 50 dwelling houses (for the most part frame buildings), 3 mercantile stores, 4 taverns, and one school."[39] The "mechanics" located in the town included boot and shoe makers, saddlers, blacksmiths and tailors. The town's population totalled 200, of which four attorneys and two physicians comprised the professions. Somewhat later, the town's industry was augmented by establishment of the Cooper Carriage Works on the turnpike west of the courthouse.[40]

This growth of services around the seat of the county government was an added inducement for the County's residents to gather in town when court was in session, to trade, transact their business at the courthouse, and exchange the news of the day. By the 1830's the schedule of court days had expanded to include sessions of the County Court (3d Monday each month), the Quarter Sessions (in March, June, August and November), and the Circuit Superior Court (25th of May and October).[41]

At these times the court would sit for several days—as long as necessary—to complete the County's business. A quorum of the total panel of appointed justices was necessary to conduct the court, but this number generally was small enough so that no hardship was suffered by those who had to leave their private concerns. In every third month, the meetings of the court would also be the occasion for convening the successor to the colonial courts of the Quarter Sessions, at which criminal charges not involving capital punishment were tried.

Throughout the first half of the nineteenth century, the sessions of the County Court continued to be the chief feature of life in the town of Providence, or Fairfax Court House, as it frequently was called. When the court was not in session, the regular passage of carriages, wagons, and herds along the Little River Turnpike was the main form of contact which residents had with areas outside the locality. This situation[Pg 15] continued even after the coming of the railroads, for when the Orange & Alexandria Railroad was chartered in 1848, its route was laid out several miles south of Providence. Thus, the nearest rail stations for the courthouse community were at Fairfax Station, on the Orange & Alexandria Railroad, and at Manassas, where the Manassas Gap Railroad left the Orange & Alexandria and ran to Harrisonburg.[42]

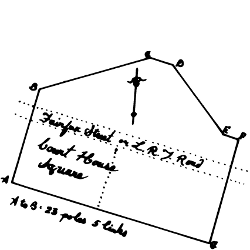

Four acres of Richard Ratcliffe's land near Caleb

Earp's Store laid off for the courthouse and other public buildings.

Record of Surveys, Section 2, p. 79, 1798.

Four acres of Richard Ratcliffe's land near Caleb

Earp's Store laid off for the courthouse and other public buildings.

Record of Surveys, Section 2, p. 79, 1798.VIEW LARGER IMAGE |

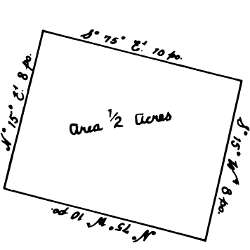

Ten acres of land surrounding the courthouse laid off

for the prison bounds. Record of Surveys, Section 2, p. 93, 1800.

Ten acres of land surrounding the courthouse laid off

for the prison bounds. Record of Surveys, Section 2, p. 93, 1800.VIEW LARGER IMAGE |

Ten acres of land surrounding the courthouse intended

for the prison bounds. Fairfax County Deed Book V-2, p. 208, 1824.

Ten acres of land surrounding the courthouse intended

for the prison bounds. Fairfax County Deed Book V-2, p. 208, 1824.VIEW LARGER IMAGE |

One-half acre, part of the four-acre courthouse lot,

laid off for the Clerk of the County and his successors. Record of

Surveys, Section 2, p. 115, 1799.

One-half acre, part of the four-acre courthouse lot,

laid off for the Clerk of the County and his successors. Record of

Surveys, Section 2, p. 115, 1799.VIEW LARGER IMAGE |

[23] Fairfax County Court Order Book, 1789–1791, p. 93.

[24] Ibid., pp. 189–191.

[25] Fairfax County Deed Book B-2, pp. 373–377.

[26] Columbia Mirror & Alexandria Advertiser, June 19, 1798. John Bogue had arrived in the United States with his family in 1795. On June 20, 1795, the Alexandria Gazette published his signed statement thanking the captain of the ship "Two Sisters" for a good voyage. In the August 1, 1795 issue of the Gazette, he advertised as a joiner and cabinet maker on Princess Street near Hepburn's Wharf, "hoping to succeed as his abilities shall preserve him deserving."

[27] Fairfax County Deed Book, B-2, p. 503.

[28] Fairfax County Record of Surveys, 1742–1850, p. 115.

[29] Fairfax County Deed Book, B-2, p. 503.

[30] Interview with former Clerk of Courts, Thomas Chapman of Fairfax, Virginia, February 13, 1970.

[31] One of the items to come before the court at this session involved winding up the county's contract with John Bogue and Mungo Dykes. The Court's Clerk, Robert Moss, was summoned to appear and show cause why he had not paid the contractors in conformance with the commissioners' report accepting the buildings. Moss produced a receipt for this payment, signed by Mr. Bogue's agent, who apparently had not passed it along to his principal. Fairfax County Court Order Book, 1799–1800, p. 509.

[32] Powell, Old Alexandria, p. 38.

[33] Elizabeth Burke, "Our Heritage: A History of Fairfax County", Yearbook of the Historical Society of Fairfax County, 1956–7, 5:4.

[34] Ibid., 32.

[36] Rust, Town of Fairfax, p. 3.

[37] Gerard Bolling was the father-in-law of Richard Ratcliffe who had provided the four-acre tract on which the courthouse had been built. Rust, Fairfax, p. 31.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Joseph Martin, Gazetteer of Virginia and the District of Columbia, (Charlottesville, 1835), p. 168. The name "Providence" apparently was less favored than the traditional Virginia style of referring to the seat of county government.

[40] Rust, Fairfax, p. 37.

[41] Martin, Gazetteer, pp. 168–169.

[42] Marshall Andrews, "A History of Railroads in Fairfax County", Yearbook of the Historical Society of Fairfax County, III (1954), 30–31.

THE COUNTY COURT AND ITS OFFICERS

In colonial Virginia local government was centered in the County Court. Its origins as a political and social institution have been attributed to various prototypes in Tudor and earlier English history. By the time Fairfax County was established in 1742, this institution and its functions in colonial Virginia had been clearly formulated and accepted.[43]

The County Court evolved from the colony's original court established at Jamestown and consisting of the Governor and Council sitting as a judicial tribunal. In 1618, the Governor ordered courts to be held monthly at convenient places throughout the colony to save litigants the expense of traveling to Jamestown. Steadily the numbers of these courts increased and their jurisdiction expanded until, by the end of the seventeenth century, these local courts could hear all cases except those for which capital punishment was provided. In effect, their jurisdiction combined the contemporary English government's King's Bench, Common Pleas, Chancery, Exchequer, Admiralty, and Ecclesiastical courts.

During this period the local courts acquired numerous non-judicial responsibilities connected with the transaction of public and private affairs. Because of both tradition and convenience, the County Court was the logical agency to set tax rates, oversee the survey of roads and construction of bridges, approve inventories and appraisals of estates, record the conveyance of land, and the like. Therefore, the court's work reflected a mixture of judicial and administrative functions, and the officers of the court became the chief magistrates of the Crown and of their communities. Once this pattern of authority and organization was developed, it continued with very few basic changes throughout the eighteenth and most of the nineteenth centuries.

Highest in the hierarchy of the officers of the county and the court were the justices. Originally designated as "commissioners", and, by the 1850's referred to as "magistrates", their full title was "Justice of the Peace" after their English counterparts of this period.[44] Popular usage in Virginia, however, fostered the custom of speaking of the members of the[Pg 19] court as "Gentleman Justices". They were both the products and caretakers of a system that placed control of public affairs in the hands of an aristocratic class, and at any time in the County's history up to mid-nineteenth century a list of the County's justices was certain to include the best leadership the County had.

Appointments were for life, and lacked any provision for compensation. Service on the court was, therefore, considered an honorable obligation of those whose position and means permitted them to perform it. That this was considered a serious and active responsibility was indicated by the fact that justices could be fined for non-attendance at court.[45] Through the colonial period and well after the War of Independence the justices of the county court were appointed by the governor, and, although episodes during this period indicated the recurrence of friction between the governor and General Assembly over the power to make these appointments, neither the local court nor the Assembly was able to assert permanently its claim to participate in the appointment process.[46] The number of justices of the county court varied considerably in different counties and times. By law the number was set at eight members; yet in 1769 Fairfax County had 17 justices, and appeared to be typical of other counties in the region.[47]

Appointments to the county court in some instances seemed almost hereditary, for when a justice of one of the prominent local families died or retired to attend to other interests it frequently occurred that his place was taken by a younger relative. Historian Charles Sydnor has noted that during the twenty years prior to the War of Independence three-fourths of the 1600 justices of the peace appointed in Virginia came from three hundred to four hundred families.[48]

Directly or indirectly, the justices of the county court influenced the selection of all other county officers. The clerk of the court was elected outright, but others—including the sheriff, coroner, inspectors and commissioners for special duties, and militia officers below the rank of brigadier—were commissioned by the governor from lists submitted by the justices.

The office of clerk of the county court presumably dates from the origin of the court itself, for references to clerk's fees are found in the law as early as 1621,[49] and authority for appointment by the governor is noted in 1642.[50] From the tables of fees authorized by law, one may see that the clerk performed a wide range of functions growing out of the work of the court.[Pg 20] These included issuing orders for all stages of court proceedings, taking depositions and inventories, recording documents, and administering or probating estates of all kinds. In addition, the county's records of births, deaths and marriages were maintained from reports made to the clerk. In time, some of the tasks of issuing certificates—such as marriage licenses—which started as duties of the court were turned over to the clerk to perform.[51]

Frequently the clerk could and did exercise great influence with the justices in the handling of legal matters. As the members of the court were laymen, it often occurred that the clerk was the only person who was learned in the law, and his advice must have been a determining factor in many situations. His tenure in office also strengthened his position of influence, for it was customary to retain clerks in office for long periods of time, during which they had daily contact with the workings of the law and events in the county. Unlike the justices, who came from all parts of the county and seldom were present except on court days, the clerk was much more available at the courthouse, and so generally was the first to hear news from the colonial capital or the outside world. As a result, the clerks of the court were consulted on a variety of matters whenever a justice was not available.

Fees charged for performing the various services connected with the work of the court made up the income of the clerk, and occasionally the same person might hold the positions of clerk and surveyor, notary, or special commissioner. Under certain circumstances, clerks also could practice law, and all of these sources combined to produce an income which was for the times comfortable.

In the eighteenth century, two significant changes in the law prescribing the clerk's office occurred—it was made a salaried position, and the county court was given full authority to appoint the clerk—but in other respects the office was changed very little either by the passage of time or the transformation from colony to commonwealth.

Ranking roughly equal to the clerk in importance to the operations of county government was the sheriff. The office of sheriff appeared when counties began to be established in the 1630's; and until after the War of Independence, sheriffs were appointed by the governor on recommendation of the county court. Almost from the beginning, too, it appears to have been customary to appoint deputies or "under-sheriffs". So it is not surprising to find that after 1661 it was customary for the[Pg 21] office of the sheriff to rotate annually among the members of the court who, in turn, appointed their deputies directly. But in the eighteenth century this system proved too disruptive, and deputies were retained throughout several terms of sheriff's appointments.[52]

From the beginning the sheriff and his deputies were compensated by fees which they collected for a wide variety of duties. These ranged from tasks connected with execution of the court's orders in criminal cases, to enforcement of the law and administration of the jail. In addition, the sheriff was due a fee from a master whose runaway servant or employee he apprehended and returned, or for collecting private debts or administering corporal punishment to servants for their owners.[53]

Sheriffs also collected the levies which financed county government. However, being subject to the pressures of their own circumstances, there often was a tendency to give first priority to activities which brought in their own fees. This led the General Assembly to require that sheriffs collect public levies before they take any fees for themselves, and to prescribe a number of other rules for improvement of the conduct of their offices.[55]

The role of the sheriff in the tax collection process always was a difficult one. The procedure for financing the county, initially, was for the justices simply to compile lists of their expenses and the freeholders of the county, compute how much was needed from each freeholder to cover the cost of government, and direct the sheriff to collect it. When the sheriff made his return to the court he was entitled to deduct a percentage as his commission.[56] However, revenue was often not collected, either because the job was farmed out to others who defaulted, or the county was too poor, or its residents were scattered and could not be found.[57] These problems ultimately led the General Assembly to establish other officers whose exclusive duties were the levying and collecting of revenue, but throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the sheriff performed a central role in the revenue process.

The sheriff was also the custodian of the county jail and its prisoners. He had the authority to decide on and collect bail, and he was liable for a fine if a prisoner escaped. He appears generally to have taken his responsibility for the county jail lightly, for there is evidence of widespread[Pg 22] contracting for others to provide the guard for the jail and the food for the prisoners. Other officials who were part of the colonial county government performed specialized functions, but unlike the clerk and sheriff, took no part in the general administration of county business.

The office of county surveyor was created early in the seventeenth century to meet the obvious need for accurate measurement and recording of land. Initially, the surveyor was appointed by the county court, and sometimes treated as an additional duty of the clerk or sheriff. However, by the end of the eighteenth century a significant change had occurred in the legislation which called for appointment by the governor after a candidate had been examined and approved by the faculty of the College of William & Mary. By 1783, therefore, the surveyor became the first county official to be required to show professional competence as a condition of appointment.[58]

The office of constable appeared in 1645, and may be described as similar to that of sheriff, except that it served the court of a single justice.[59] Constables were appointed by the justices of the county court and served in precincts delineated by the justices.

The function of coroner in colonial Virginia was similar in all essential respects to that in England at that time, that is, to represent the Crown by investigating the circumstances of unexplained deaths. Originally, this function was performed by the justices, acting without fee. However, by the 1670's, coroners were being appointed by the governor, and authorized to collect fees for their services from the estate of the deceased or, lacking that, from the county. In the absence of the sheriff, the coroner could be designated by the court to perform the duties of the sheriff's office.[60]

Roughly a century after the appearance of the coroner, the next significant addition to the machinery of county government came with the creation of the commissioners of the tax. Forced by the increased military expenses of the 1760's and 1770's[61] to find new sources of revenue, Virginia created an official to take over the specialized function of assessment of property for tax purposes. He was elected by the freeholders of the county. In office, his task became one of laying off the county into districts, assessing property, and notifying the owner of the tax due.

[Pg 23]The commissioners of the tax were created in 1777, and lasted until 1782 when a new official, the commissioner of the revenue was established.[62] The new commissioner took responsibility for making assessments of taxable property under a simplified procedure, and the office has remained as a unique feature of Virginia's local government to the present time.

As the institution of the county court grew during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and became the hub of county government, the monthly sessions of the court furnished an opportunity for general gatherings of the county's residents and visitors to transact both public and personal business. A scene that must have been typical of almost any Virginia county in the early nineteenth century has been described by historian John Wayland as follows:

Court day once a month was looked upon as a great event; everyone that could leave home was at hand. It was a day of great interest; farmers coming in with their produce, such as butter and eggs, and other articles which they exchanged for groceries and dry goods. The streets around the courthouse were thronged with all sorts of men; others, on horseback, riding up and down trying to sell their horses. Men in home made clothes, old rusty hats that had seen several generations, coarse shoes and no stockings, some without coat or vest, with only shirt and pants....

This was a day to settle old grudges. When a man got too much whiskey he was very quarrelsome and wanted to fight.... It was, also, a great day for the gingerbread and molasses beer. The cake sellers had [tables] in front of the courthouse, spread with white cloths, with cakes piled high upon them and with kegs of beer nearby. I have seen the jurymen let down hats from the windows above, get them filled with gingerbread and a jug of beer sent up by rope. About four or five o'clock the crowd began to start for home.[63]

For anyone who had business with the court, whether he or she came as a petitioner or a penitent, the justices, clerk, sheriff, and other officials represented the presence of power and authority as colonial Virginia knew it. But it was a presence in which men stood on little ceremony or formality with each other. Except in unusual circumstances all were likely to be laymen, for in colonial Virginia there was little[Pg 24] formal education in the professions and, at most, one might have attended lectures at the College of William & Mary or a school in England. If the gentlemen justices were widely read in history, philosophy, government and literature—as well they might be—these advantages of their means and leisure did not destroy their appreciation for the issues they were asked to decide. For in their own right they were planters who had to face and deal with these issues in their own lives. Accordingly, their decisions, as reflected in the minutes of their sessions, were based on this realism which comes from personal experience.

Yet it remained true that the gentlemen justices of the county court were, for most practical purposes, beyond any control of the community they governed. Any complaint about the manner in which the justices conducted their business could only be directed to the governor.[64] Should the court cease to function for long periods of time because of quarreling among the justices, or should the occurrence of an emergency require replacement of justices, the freeholders of the county had no method of dealing with their problem except through the pressure of public opinion.[65]

Even with the best of good will among the members of the court, they could not escape the usual difficulties of handling legal matters before a bench of lay judges, who not only lacked professional training, but were handicapped by the scarcity and cost of law books.[66] Decisions which seemed wrong could, from earliest colonial times, be appealed to the governor and General Court. Later the establishment of District Courts, and their successors the Circuit Courts, provided an intermediate tribunal for determining matters which turned on points of law. But the business of the gentlemen justices on court days was a mix of legal and administrative matters, and in the latter area of activity there was no appeal.

Among the non-judicial activities carried on at the courthouse, none was as colorful and few were more important than elections of members of the House of Burgesses. Elections were ordered by writs issued by the governor, and in each county they were conducted by the sheriff. Unless reasons of the greatest gravity prevented it, the polling place was the county courthouse.[67]

Voting, or "taking the poll" as it was called, was conducted in the court chambers, or, in warm weather, in the courthouse yard, with the sheriff presiding at a long table. On[Pg 25] either side of the sheriff were justices of the court, and at the ends of the table were the candidates and their tally clerks.

The sheriff opened the election by reading the governor's writ and proclaiming the polls open. If there was no contest or a clearly one-sided election, the sheriff might take the vote "on view"—that is, by a show of hands of those assembled at the courthouse. Generally, however, a poll of the individual voters was taken. As the polling went on, each freeholder came before the sheriff when his name was called and was asked by the sheriff how he voted. As he answered, the tally clerk for the candidate receiving the vote enrolled it and the candidate, in his turn, generally acknowledged the vote with a bow and expression of appreciation. At the close of the polling a comparison of the tally sheets showed the winner.

This method of voting enhanced the excitement of a close election, and, since elections frequently were held on court days when many people came to the courthouse on other business, activity outside the courthouse sometimes was spirited. Wagers were offered and taken, arguments broke out and fights sometimes followed.[68]

Those attending the elections usually were in good spirits, for they were aided by the custom of the candidates to provide cider, rum punch, ginger cakes, and, generally, a barbecued bullock or pigs for picnic-style refreshment of the voters waiting at the courthouse.[69] The candidates and their friends also kept open house for voters traveling to the courthouse on election day, offering bed and breakfast to as many as came. On election night, the winning candidates customarily provided supper and a ball for their friends and other celebrants.[70] The law was explicit that no one should directly or indirectly give "money, meat, drink, present, gift, reward or entertainment ... in order to be elected, or for being elected to serve in the General Assembly",[71] but the practice of treating the voters on election day was deeply rooted in Virginia's political tradition. Thus the law was interpreted as only prohibiting one offering refreshment "in order to get elected"—something extremely difficult to prove—but not preventing one from treating his friends. So, while occasionally voices were heard to condemn candidates for "swilling the planters with bumbo",[72] or bemoan the "corrupting influence of spiritous liquors, and other treats ... inconsistent with the purity of moral and republican principles", the complainants almost always turned out to be candidates who themselves had recently been rejected at the polls.[73]

The War of Independence caused little change in Virginia's system of county government. The county court system was carried over into the state constitution of 1776 with only the oath of office changed to call for support and defense of the constitution and government of the Commonwealth of Virginia.[74] The General Assembly became the successor to most of the functions of the colonial House of Burgesses and Governor in Council, but significantly the principle of the separation of powers established for the commonwealth was not extended to the counties. Thus, the mix of powers, privileges and duties which comprised the authority of the gentlemen justices in colonial times was continued, as was the custom of appointment for life.

How little the transition from colony to commonwealth changed the justices' own view of their position was illustrated in 1785 when the new governor issued new commissions reappointing the justices of Fairfax County's court. The justices refused to accept the new commissions, and pointed out to the governor in a long letter that this duplication of oaths would set a bad precedent and risk giving the executive undue powers over the court. Far from being an artificial objection, the letter noted, this latter point was extremely touchy for the justices' standing in a great many matters was based on seniority, and both the prestige and chances for financial rewards that went with the office depended on this standing.[75]

The most noteworthy changes in the organization of local functions came as a result of the disestablishment of the Church of England. That portion of all local officials' oaths which called for supporting and defending the church was dropped, but, more important, abolition of the parish vestry made it necessary to lodge its non-religious functions elsewhere. In 1780, therefore, the General Assembly created county boards of Overseers of the Poor.[76] Most other welfare activities were added to the responsibilities of the county court.[77]

While the basic philosophy of Virginians regarding their local government did not change as a result of independence, certain new governmental institutions were created because colonial ways were not efficient enough to meet the demands placed on them by social and economic growth. Although the general jurisdiction of the county court was continued, in 1788 a new court, called the district court, was established to relieve the pressure of judicial business.[78] These district courts were the direct antecedents of the present circuit courts of the counties which were created by the General Assembly in 1818.[79]

[Pg 27]If the district court did not displace the county court immediately, it forecast its eventual decline as a judicial tribunal. The new court introduced the beginnings of professionalism on the bench, and offered the prospect of full-time attention to the administration of justice by trained judges. Establishment of the office of the Commonwealth Attorney in 1788 added to this trend toward professionalism.[80]

Most of the administrative duties of the county court in colonial times remained after independence. Consequently, the records of the county court continued to show actions connected with the licensing of inns, ordinaries, mills, ferries, peddlers, and other similar activities, along with attention to the survey and maintenance of roads, bridges, and fords.[81] Regulatory powers over the practices of tradesmen and artisans was broad, and used by the county court to set rates which could be charged and to prescribe trade practices which affected the quality of the products involved.

In this area of activity, the county court was performing what Virginians generally regarded as matters of purely local concern. Except in connection with the production of tobacco and milling and shipping of grain, economic activities seldom affected anyone beyond the county neighborhood.[82] Therefore, the county court was deemed to be the best body to understand and accommodate the interests involved. This attitude began to change only as the improvement of transportation facilities increased travel and commerce in the period from 1830 to 1860.

[43] See generally, Martha Hiden, How Justice Grew: Virginia Counties: An Abstract of Their Formation, (Williamsburg: Virginia 350th Anniversary Celebration, 1957). Also, because time-honored tradition as well as law influenced the organization of Virginia counties, the description of English local government in J. B. Black, The Reign of Elizabeth, 1558–1603, (Oxford: Oxford University, 1936), pp. 174–177, applies to Virginia's county government in the colonial and early federal periods.

[44] The first statute on this subject, in 1628, used the term "commissioners" (I Hening, Statutes, 133). In 1662, this term was replaced by "justices". P. A. Bruce, Institutional History of Virginia in the Seventeenth Century, (New York: Putnam, 1910), I, 488. However, Porter, County Government, p. 170, states that "justice of the peace" was the full title during most of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

[45] Porter, County Government, p. 168.

[46] In 1657, for example, the House of Burgesses enacted legislation requiring that appointments be recommended by the county court and approved by the Assembly. (I Hening, Statutes, 402, 480) But this requirement appears to have been repealed after the restoration of Charles II.

[47] Porter, County Government, p. 49, cites the Calendar of State Papers, I, 261, listing the numbers of justices in nearby counties as follows: Fauquier, 18; Prince William, 18; Loudoun, 17.

[48] Charles Sydnor, American Revolutionaries In The Making, (New York: Collier, 1962), p. 64.

[49] Hening, Statutes, I, 117.

[50] Hening, Statutes, I, 305.

[51] Hening, Statutes, II, 28, 280.

[52] Porter, County Government, p. 42.

[54] Hening, Statutes, I, 330, 484.

[55] These rules included prohibitions against extortion of excessive fees, acting as lawyers in their own courts, falsifying revenue returns, multiple job-holding and the like. See Hening, Statutes, I, 265, 297, 330, 333, 465, 523; II, 163, 291. Porter, County Government, 68, comments that "the office of sheriff, judging from the number of acts which the assembly found it necessary to pass, was the problem child of ... [the 18th century], not only in regard to the duties of the office, but also in the method of appointment."

[56] Shepherd, Laws of Virginia, I, 367.

[57] Calendar of State Papers, IV, 416.

[58] Hening, Statutes, XI, 352.

[59] Hening, Statutes, IV, 350.

[60] Hening, Statutes, II, 419; IV, 350.

[61] Hening, Statutes, IX, 351.

[62] Hening, Statutes, XII, 243.

[63] John Wayland, History of Rockingham County, Virginia, (Dayton, Virginia: Ruebush-Elkins, 1912), pp. 424–425.

[64] Porter, County Government, p. 109, citing Calendar of State Papers, IV, 170.

[65] Sydnor, American Revolutionaries, pp. 77–78.

[66] As a result law books were the property of the court rather than the individual justices, and on the death or resignation of a justice his law books were surrendered to the court and divided among the remaining members of the court. Hening, Statutes, IV, 437.

[67] In unusual circumstances, such as an outbreak of smallpox, the sheriff might chose an alternate site. H. R. McIlwaine (ed), Journals of the House of Burgesses, 1742–49, (Richmond, 1909), p. 292.

[68] [Pg 30]Douglas S. Freeman, George Washington: A Biography: Young Washington, (New York: Scribner, 1948), II, 146, notes that Washington became involved in an election-day brawl at the election of members of the House of Burgesses in December 1755. The contest between John West, George William Fairfax, and William Ellzey was very close, and Washington (supporting Fairfax) met William Payne (who opposed Fairfax). Angry words led to blows, and Payne knocked Washington down with a stick. There was talk of a duel, but the next day Washington apologized for what he had said, and friendly relations were restored.

[69] Sydnor, American Revolutionaries, p. 53.

[70] Nicholas Cresswell, The Journals of Nicholas Cresswell, 1774–1777, (Pt. Washington, N. Y.: Kennikat Press, 1968), pp. 27–28.

[71] Hening, Statutes, III, 243.

[72] "Bumbo" was an eighteenth century slang term for rum. Sydnor, American Revolutionaries, p. 53.

[73] William C. Rives, History of the Life and Times of James Madison, (Boston: Little, Brown, 1873), I, 180–81.

[74] Porter, County Government, p. 107.

[75] Calendar of State Papers, IV, 337.

[76] Hening, Statutes, X, 198; XI, 432; XII, 273, 573; Shepherd, Laws, I, 114.

[77] Hening, Statutes, X, 385 (orphans); XII, 199 (mental health).

[78] The district court's jurisdiction included civil cases of a value of £30 or 2,000 lbs of tobacco, all criminal cases, and appeals from the county court in criminal cases. Hening, Statutes, XII, 730 et seq.

[79] Virginia, Code of 1819, I, 226.

[80] Hening, Statutes, XIII, 758.

[81] Hening, Statutes, XII, 174.

[82] [Pg 31]In the late eighteenth century, Virginia millers and warehousemen were major sources of grain and flour for New England, the West Indies and Mediterranean. The House of Burgesses, and later the General Assembly, enacted comprehensive laws regulating the quality, grading and marking of these products. See, Lloyd Payne, The Miller in Eighteenth Century Virginia, (Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg, 1963) and Charles Kuhlman, The Development of the Flour-Milling Industry in the United States, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1929), pp. 27–33, 47–54.

THE WAR YEARS: 1861–1865

As events in the winter of 1860 and the spring of 1861 carried the nation into the crisis of civil war, Fairfax County aligned itself with Richmond rather than Washington. Thus, at the State's convention on secession in May 1861, the Fairfax County delegation voted to ratify the secession ordinance.[83] The consequences of this action were prompt in coming and far-reaching in their effects, for with the commencement of military operations in Northern Virginia it became impossible to carry on the normal processes of county government.

Fairfax Court House (the Town of Providence) was outside the ring of fortifications which were built on the Virginia side of the Potomac to protect the National Capital. Inside this line, stretching in a great arc from Alexandria, through the vicinity of The Falls Church, to Chain Bridge, Union Army commanders exercised military authority and administered justice through provost courts.[84] Outside this area the authority of the General Assembly of Virginia nominally remained in effect, and the justices of the courts and the sheriffs of the county continued to hold their positions under the laws of the seceded state.

Serious difficulties in the transaction of public business soon appeared throughout Fairfax County, where patrolling and skirmishing outside the ring of permanent fortified positions were daily occurrences. This was recognized in an ordinance adopted by the Secession Convention providing that when the court of any county failed to meet for the transaction of business or the public was prevented from attending the court "by reason of the public enemy", the court of the adjoining county where such obstructions did not exist had jurisdiction of all matters referrable to the court or the clerk of the court where normal business had ceased.[85]

As Virginia armed, troops of the Confederacy placed themselves in positions to repel invaders, and in May 1861, a company of the Warrenton Rifles established a camp at Fairfax Court House. On the morning of June 1, 1861, a body of Union cavalry rode through the town, and in the confused exchange of fire which followed, a Captain of the Rifles, John Quincy Marr, became the first officer casualty of the war.[86]

[Pg 34]A month later, the tide of Union forces under McDowell swept past the courthouse on the way to its rendezvous at Bull Run, and back again to the safety of the fortified positions along the Potomac. In the wake of their victory at Bull Run, troops of the Confederacy established an outpost at Fairfax Court House to watch for signs that the Union Army might resume the offensive by moving against the Confederate earthworks near Centreville.

This outpost did not see any fighting for the time being, but it provided the site for what later was regarded as one of the decisive moments of the war. In September 1861, General Beauregard had established his headquarters at Fairfax Court House, and urgently pressed the newly-formed government of Confederate President Jefferson Davis for reinforcements with which to sweep into Pennsylvania and Maryland and, hopefully, to carry the Federal capital itself. A meeting was arranged at Beauregard's headquarters in which Davis, Generals Beauregard and J. J. Johnston, and certain of their trusted staff officers considered this plan. Their decision was to adopt a defensive posture and protect the borders of Virginia rather than take the offensive and invade the North. As events turned out, this decision had consequences of the greatest effect, for it was not until Lee marched out of the Valley on the road to Gettysburg in 1863 that there was another opportunity for the Confederacy to carry the war to the soil of the northern states.[87]

In the spring of 1862, the Confederate army retired from Fairfax Court House, and soon after that its line of fortifications at Centreville—the most extensive system of field fortifications in military history up to that time—was abandoned. As the Union armies took the initiative in their repeated efforts to reach Richmond, the crossroads at Fairfax Court House had key importance in the communication and supply systems of these forces.

From 1862 to the end of the war, Union troops remained in control of the crossroads and the courthouse. Contemporary photographs of the building show it being used as a lookout point and station for patrols. Other descriptions indicate that the courthouse was loopholed,[88] the furnishings were removed, and the interior generally was gutted so that only the walls and roof remained.[89] For all practical purposes, the courthouse and its related buildings were, in the years 1863 and 1864, a military outpost and minor headquarters in the Union army's system to protect its supply and communications lines from the irregular troops who kept hostilities constantly smoldering in Northern Virginia. Throughout the western part of Fairfax County, and in Loudoun, Fauquier and Prince[Pg 35] William Counties, lived many who gave the appearance of innocent farmers during the daylight hours, but who changed into Confederate uniforms at night and on weekends to ride against isolated outposts or supply points of the Union army or destroy vulnerable bridges and communications centers.

The operations of these guerilla bands kept thousands of Union troops pinned down on rear area security guard duty, and preoccupied the forces assigned to Fairfax Court House. The difficulty of their task under the circumstances that prevailed in Northern Virginia was dramatized in the famous Confederate raid on Fairfax Court House by men under the command of Col. John S. Mosby when, on the night of March 8, 1863, the Confederate commander with about 30 men captured and carried off 33 prisoners, including Union Brigadier General Edwin H. Stoughton, and a large number of horses and quantity of supplies. Throughout 1863, 1864 and the spring of 1865 hardly a night went by without some cries of alarm and shots being fired because of the activities of the Confederate irregulars. Yet they took a substantial toll from the wealth and welfare of the very people they claimed to represent, for the Union troops soon learned more efficiency in their rear area operations, and increased the restrictions on movement of civilian traffic. The transaction of personal business in normal ways became virtually impossible. The historian, Bruce Catton, has assessed the activities of the guerilla bands as follows:

The quality of these bands varied greatly. At the top was John S. Mosby's courageous soldiers led by a minor genius, highly effective in partisan warfare. Most of the groups, however, were about one degree better than plain outlaws, living for loot and excitement, doing no actual fighting if they could help it, and offering a secure refuge to any number of Confederate deserters and draft evaders.... The worst damage which this system did to the Confederacy, however, was that it put Yankee soldiers in a mood to be vengeful.[90]

During the years when normal business at the courthouse was suspended and the county officials who held authority from the General Assembly were dispersed, some of the county's records were removed from the courthouse for safekeeping, and some were not.[91] In either case they were subject to the risks of loss and damage. Some were carried off and in later years have been brought to light as the descendents of Union and Confederate soldiers have found them in places where they had been put for safekeeping.

[Pg 36]The jail building ceased to be used for its original purpose, and, during the latter months of the war, the jail of Alexandria County (now Arlington County) was utilized for Fairfax County's prisoners.[92]

The effort to provide a legitimate successor to the secession government in Richmond started in the Wheeling Conventions of May and June 1861, from which came the Unionist government of Francis H. Pierpont.[93] The admission of West Virginia to the Union in December 1862[94] left Governor Pierpont in control of only those parts of Northern Virginia, the Shenandoah Valley, and Chesapeake Bay that were occupied by Federal troops. Within this area, the Pierpont administration collected taxes and attempted to supply the essential services of civilian government. Closer touch with these problems was possible after June 1863, when Governor Pierpont moved his government to Alexandria.

On January 19, 1863, a new County Court for Fairfax County was convened pursuant to a proclamation by Governor Pierpont which directed that the place for the court's sessions should be changed from Fairfax Court House to the Village of West End[95] near Alexandria. Here, in January 1863, the Court met in a structure known as Bruin's Building. The minutes of this and other sessions which followed recite many of the same problems and disputes that always had occupied the time of county courts—dockets of minor criminal and civil cases, petitions to higher levels of government, determination of minor civil disputes, issuances of permits and licenses, and appointment of public officials.[96]

Certain items in the minutes of this January 19, 1863 meeting documented the strains created by the wartime conditions: a petition to the Secretary of War prayed that the "Bruin Building" in the Village of West End be placed at the court's disposal; the Deputy Commissioner of Revenue was directed to discharge the duties of the Commissioner until the latter, currently a prisoner in Richmond, could return to his duties; payments were approved for wagonowners who had hauled books, papers and records to the courthouse from various points in Fairfax and nearby counties. One item of particular interest stated:

The fact having been brought to the notice of the Court that degradations were being committed upon the Mt. Vernon Estate, the Court, under the Chancery powers vested therein, appointed Jonathan Roberts, the present Sheriff, Curator, to take charge of all[Pg 37] property in Fairfax County, Va. belonging to the heirs of John A. Washington, dec.[97]

After the cessation of fighting in April 1865, Governor Pierpont moved his government from Alexandria to Richmond. However, without the presidential support which Lincoln had provided during his lifetime, the Pierpont administration found it increasingly difficult to carry on effective government as the years immediately after the war saw numerous plans for reconstruction competing for favor. The situation was further complicated by the fact that in February 1864 the Pierpont administration had sponsored a constitutional convention which had adopted a new constitution for Virginia, and that this constitution had nominally gone into effect in Alexandria and Fairfax counties.[98] A complex legal problem regarding the succession of governmental authority thus was added to the formidable task of reconstructing Fairfax County's economy and physical facilities.

This task was made difficult because many of the records of the County had been scattered or destroyed during the fighting. Records were searched out and retrieved whenever their places of safekeeping were known, a process requiring years of effort. Some record books were never found. The accounts of how the wills of George and Martha Washington were recovered are frequently cited to illustrate the difficulties of reassembling Fairfax County's records.

When, in the fall of 1861, Beauregard's Confederate troops withdrew from Fairfax County, the will of George Washington was secretly removed from the courthouse by the court clerk, Alfred Moss, and taken to Richmond. Here it was placed for safekeeping with the Secretary of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Following the cessation of hostilities, it was returned to Fairfax County.[99]

Martha Washington's will was not removed from the courthouse to Richmond, but remained there during the time Union troops occupied the building as a patrol point. As might be expected, cabinets were broken open and papers scattered. One day, late in 1862, a troop of soldiers from New England was in the building and engaged in shoveling out the debris from the floor. A Union lieutenant named Thompson grew curious about these papers and interrupted the work long enough to examine some of them. He picked up the will of Martha Washington and, recognizing it, took it with him. Following the war, the will next was heard of in 1903 in England where a descendant of[Pg 38] Lt. Thompson sold it to J. P. Morgan. The sale was reported to the Commonwealth Attorney of Fairfax County who wrote Mr. Morgan seeking the return of the will, but no answer was ever received. After Mr. Morgan's death, the County sought to obtain the will from his son. Negotiations were unsuccessful until court action was begun by the County. Finally, one day before the matter was to be argued before the United States Supreme Court, the will was returned.[100]

[83] Thomas Chapman, Jr., "The Secession Election in Fairfax County, May 23, 1861", Yearbook of the Historical Society of Fairfax County, IV (1955) 50.

[84] Robert Anderson, "The Administration of Justice in the Counties of Fairfax, Alexandria (Arlington) and the City of Alexandria (Part II)", The Arlington Historical Magazine, II (October 1962) 10–11.

[85] Ordinance 67, passed by the Virginia Convention, 26 June, 1861, cited by Anderson, "Administration of Justice", p. 10.

[86] Governor William Smith, "The Skirmish at Fairfax Court House", The Fairfax County Centennial Commission, (Vienna, Virginia: 1961) p. 4. Because of the confusion in the Confederate ranks, no officer took charge, and so Governor Smith ordered the Confederate troops to return the fire of the Federal soldiers.

[87] The Fairfax Court House meeting, which took place in Gen. Beauregard's headquarters near the courthouse, has been the subject of controversy in the memoirs of those involved. See, for example, Jefferson Davis, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, (New York: Yoseloff, 1958), I, 368, 448–452, 464; Alfred Roman, Military Operations of Gen. Beauregard, (New York: Harper & Bros., 1884), I, 137–139.

[88] Washington Post, April 10, 1921.

[89] Alexandria Gazette and Fairfax News, October 17, 1862.

[90] Bruce Catton, A Stillness at Appomatox, (New York: Cardinal Giant Edition, Pocket Books, Inc., 1958), pp. 318–319.

[91] Two items from the Alexandria Gazette in July 1862 illustrate the problems regarding these records. The edition of July 12, 1862 printed a letter to the newspaper stating that records of Fairfax County had lately been found in Warrenton, having been removed there, it was supposed, by lawyers. The new[Pg 40] sheriff of the County took possession of these records. The edition of July 23, 1862 reported that the new County Court of Fairfax held its July term in the Clerk's office, the courthouse not being in condition for that purpose, and that one of the court's actions was to order that application be made for a new seal, the old one not being found.